Soup to Raise the Dead

Here is the pot of hot and sour soup just after being thickened with eggs and a thin slurry of cornstarch. I don’t like the soup overly thick and gloppy so I use a minimum of cornstarch in it.

Shiksa Ball Soup may have marvelous healing powers, but it does lack the ability to raise the dead.

Hot and Sour Soup takes up where the shiksa balls leave off. It can, by virtue of its bold and vivacious flavors, awaken the most hung-over sot from an alcohol induced coma. I am sure of it. I know, because, in my youth, I often was that hung-over sot.

Back when I was in college the first time, long ago in the “stone knives and bearskins era” of computers before the Internet, I was a partier. Being such, I discovered that the best way to break my fast and awaken to the world of journalistic deadlines and excitable editors who felt no compunction about screaming into reporter’s ears, was to hike on down to my most beloved of Chinese restaurants and order a steaming bowl of hot and sour soup and a pot of tea.

The fragrant tea awakened my spirit, and the hot and sour soup kick-started my recalcitrent body. After the hot and sour soup awoke my stomach and convinced my metabolism to considerreturning to resembling normal functioning, I’d have a plate of chicken with garlic sauce to really get the motor humming. After that lunch, I was ready for anything, including scowling professors who didn’t believe in foul language in the newsroom and lost feature photographs for the front page.

After I dropped out of college, and then got married, and then ended up in a messy divorce, I found myself working at my favorite Chinese restaurant.

I ended up taking a good chunk of my caloric intake in hot and sour soup. I used to buy it at the end of the night at twenty-five cents a quart, and would carry it home. Once there, I would climb out on the roof of my furnitureless rented house, and perch there with my housemate (who also worked there) , and we would drink the soup, usually directly from the container. I discovered that having no breakfast, a small lunch composed primarily of rice, a medium sized dinner of homestyle Chinese food and a midnight snack of a half quart to a quart of hot and sour soup while working double shifts as a waitress in a busy restaurant will take the pounds off of a body, very quickly.

The soup is actually quite nutritious; the version I was eating had a very little bit of shredded pork in it, along with a good bit of tofu, some mushrooms, cloud ear fungus, bamboo shoots and eggs, all cooked in a chicken broth. It was very low in fat, and high in protein and fiber. Seasoned as it was with black pepper and vinegar, it was very good for the digestion.

Later, after I went back to college in Athens, Ohio, I found another restaurant which made good hot and sour soup, and while I wasn’t a drunken sot this time around, I still found that skipping breakfast and going to early classes on coffee alone, then breaking my fast at lunchtime with hot and sour soup was a good way to really start my afternoon.

It wasn’t until I moved to Providence, Rhode Island and went to culinary school that I discovered that I needed to learn how to make hot and sour soup, since it was impossible to find a restaurant that made a good rendition of it.

I was used to eating hot and sour soup in a Sichuan restaurant, and the places in Rhode Island were great with the Cantonese specialties, but not so good with the Sichuan. Their soups were neither hot nor sour and were utterly lacking in character. One thing that hot and sour soup should never lack for is character; it is, at its best, an utterly complex brew, a wild melange of flavors, textures and scents that cannot fail to perk a body up.

So, I looked at a couple of recipes and started cooking.

Traditionally, hot and sour soup is made hot with black pepper and sour with rice vinegar. However, many restaurants in the U.S. use chile garlic paste to provide the heat, so in my first attemptsI used a teaspoon or so of that in addition to the black pepper . It turned out well, but was not as flavorful as I wanted, so, I started experimenting.

I decided to see what I could do to punch up the flavor of the broth–I ended up simmering minced ginger and garlic in the broth for at least an hour before adding other ingredients. This really worked wonders; just that little extra time made the soup that much better than before.

Three traditional ingredients in hot and sour soup are black mushrooms (dried shiitake), lily buds and tree ear or cloud ear fungus, also known as black fungus. All three of these items are dried and are available in any Chinese market, and I discovered, that the first two add huge amounts of complexity to the finished soup when used properly.

Dried ingredients for hot and sour soup. From the top left: black fungus, also known as cloud ear fungus or tree ear fungus, lily buds, also known as golden needles, and black mushroom, also known as dried shiitake mushrooms.

They all need to be rehydrated in warm to hot water before using; the first step in making my hot and sour soup is always the gathering of and rehydrating of these three ingredients. I usually only need to soak them for about twenty minutes, during which time, I have started the broth simmering.

The black mushrooms and lily buds add not only solid substance and textural interest to the soup, but they bring an extra bonus: the water I soaked them in goes into the simmering soup, adding another layer of flavor. The mushrooms add a dark, mysterious quality to the soup, while the lily buds add a piquant tang. The only caveat in using the soaking water is to always leave the last bit in the bowl; there is grit left behind from the processing of these ingredients, which you do not want in your soup. As I said about cleaning leeks thoroughly–gritty soup sucks.

Black fungus expands greatly when rehydrated. Notice how the soaking water for the black mushrooms has darkened. It is now flavored with the musky essence of the mushrooms.

Cloud ear fungus does not have any inherent flavor of its own; it is a texture food. Like jellyfish or sea cucumber, cloud ear provides a unique mouthfeel to the dishes it is added to. The Chinese love to eat things that have contrasting textures as well as interesting flavors and colors; cloud ear mushrooms provide a bit of deep black color and an interesting crunch to the soup. There is no need to try and use the soaking liquid from the fungus; it will add nothing to the broth in the way of flavor, so I usually just discard that after it is finished soaking.

While living in Providence, I ran across a huge Asian market that had a dizzying array of fresh produce; that is where I first came into contact with fresh waterchestnuts and had a conversion experience that was rather akin to Saul Paulus while on the road to Tarsus. (I know that sounds heretical, and maybe it is, but you try a fresh water chestnut and tell me it isn’t divine, especially if all you have had up until then is canned.) The place was called Mekong Market, and it was there that I found fresh galangal and lemongrass, which I bought up greedily in order to make another beloved and life-saving soup, Tom Kha Gai.

Galangal root is a hard, knobby rhizome that is related to ginger, but tastes nothing like it. It has a difficult to define flavor: medicinal but not in a Listerine-yucky sense, fragrant, with a woodlands scent, and redolent of musk and spice without being in any way hot. It is similar in flavor to black cardamom, but more complex, and once I smelled the fresh sort, I threw away all of my dried galangal and vowed never to use it again, as all of the fragrance and most of the flavor is leeched away in the drying process. I have since discovered that flash frozen galangal root carries all of the good traits of fresh, and its one bad trait is mediated: galangal root is rock hard. It takes a good heavy cleaver and a strong arm to cut it into coin-shaped slices, and when you are finished letting it bath a broth or stock with its fragrance, it is best to remove all solid traces of it, lest a diner inadvertantly chip a tooth in trying to eat it.

Lemongrass has the scent of lemon verbena, but it is more able to withstand high heat cooking. It is a stalk, and the lower third of it is used, either minced or shredded or crushed in Thai salads, noodles or curries, or, the whole stalk is crushed with a hearty blow with the side of a cleaver and is simmered in a soup, then fished out at the end of cooking.

Use the flat of the cleaver to smash the lemongrass stalks and galangal slices in order to break the fibers down and release more flavor into the sou

Having these two ingredients at hand in my refrigerator meant that it was inevitable that they got added to my hot and sour soup one day. And so, they were–I put them in with the ginger and garlic for a one hour pre-simmer, before adding all the other ingredients, and the flavors that they introduced to the brew were intoxicating and delicious. I served it at a dinner to my Chinese and Korean compatriots in culinary school, and they went wild trying to guess the mystery ingredients. Lemongrass was easy–Nee Wee, from Singapore got that one right away, but no one got the galangal. They could taste it, they knew it was there, they knew it was good, but they couldn’t figure it out until I showed them.

Since then, I have always added those two completely untraditional ingredients to my hot and sour soup, and I have never yet had a complaint from anyone. Everyone loves it. (Though, I must say, none other than Martin Yan puts lemongrass in his hot and sour soup–years after I started using it, I saw in his book, Culinary Journey Through China, that he also liked the flavor of lemongrass. I felt vindicated.)

A final non-traditional ingredient I have taken to using in my soup is Sichuan peppercorn, though, again, later, I found that at least one well-known Chinese chef and cookbook author does the same thing. Sichuan peppercorn adds significantly to the fragrance of the soup, and because I use a reasonably small amount, it does not stand out the way it does in Kung Pao dishes or Ma Po Tofu. It simply adds a floral spiciness that completely melds with the black pepper heat into a beautiful culinary liason that never fails to mystify, yet seduce my guests.

In the end, my version of hot and sour soup is very different from the one that I ate at Huy’s restaurant, and tastes nothing like any other version I have had anywhere. I have since taught the recipe to many students, all of whom say that the flavor is addictive and it ruins them for eating hot and sour soup out in restaurants. That, of course, was not my goal; I think that a good version of hot and sour soup, cooked in an authentic way is just as wonderful as my version: it is just different. Not better, not worse, just itself.

The major flavoring and texture ingredients for my version of hot and sour soup. From the far left, black fungus, fresh lemongrass, frozen galangal, fresh garlic, lily buds, black mushroom, fresh ginger, dried chile peppers, Sichuan peppercorns and black peppercorns.

Hot and Sour Soup

Ingredients:

3 quarts chicken stock or broth (For a totally vegetarian soup, use vegetable broth)

4-6 stalks lemongrass, trimmed, and cut into 3″ pieces

3 ounces galangal, fresh or frozen, cut into coin-sized slices

1″ cube fresh ginger, minced

3 cloves garlic, minced

3-5 dried Chinese chile peppers

1/4-1/2 cup Shao Sing wine or dry sherry

2 teaspoons black peppercorns

1 teaspoon Sichuan peppercorns

1″ cube ginger, peeled and cut into matchstick slivers

1/4 cup dried lily buds, rinsed and soaked in 1/2 cup warm water until softened

4 black mushrooms, rinsed and soaked in 1 cup warm water

handful of dried cloud ear, soaked in warm water

1 can bamboo shredded bamboo shoots, drained and rinsed in warm, then cold water

8 ounces firm or extra firm tofu, cut into thin strips

2 eggs, beaten

dark soy sauce to taste

chili garlic paste to taste (optional)

cornstarch slurry (optional)

white rice vinegar to taste

black rice vinegar to taste

2 teaspoons sesame oil

3 scallion Tops, finely sliced on the diagonal

handful whole cilantro leaves, rinsed, and stemmed

Method:

Put your stock or broth in a large soup pot or dutch oven. Add galangal, lemongrass, minced ginger and garlic and whole chile peppers. Cover, put it on high heat and bring to a simmer, then turn down on medium. Allow to simmer for at least one hour, covered, or until you like the amount of lemongrass and galangal flavor.

Pour in your wine or sherry.

Meanwhile, in a small skillet toast your black peppercorns and Sichuan peppercorns until fragrant. Grind them in a mortar and pestle or electric spice grinder and add them to the pot, putting the lid back on.

Using a wire skimmer, fish out galangal and lemongrass, and discard. You can leave in the chile peppers or not as you desire. Add wine, and the soaking liquids from the lily buds and black mushrooms, being careful to leave the dregs of the soaking liquid, with its attendant grit in the bowls, and discard. (Squeeze excess water out of the mushrooms and lily buds; for the mushrooms it will make them much easier to slice; besides all that good juice makes your soup broth really flavorful.)

Now, put your lily buds into the soup pot, and slice your mushrooms and fungus. Take your squeezed out mushrooms, and slice off the stems, which are too tough to eat without cooking them for a very long time. The easiest way to do this is to fold your mushroom in half, backwards, with the stem pointing outwards, and then lay it on the cutting board and slice it off. You will lose a bit of the cap, but that is okay. Then, slice the caps into thin strips.

For the black fungus, first, cut or tear off any hard bits where the fungus grew to the tree trunk. Those tough pieces never soften as they cook. Then, take each piece of fungus and roll it up cigar style, lay it on the cutting board and cut it crossways into thin strips. They unroll into little ribbons.

This is how the fungus and mushrooms should look after they are rehydrated and thinly sliced. All of the ingredients for the soup should be shredded or sliced very thinly.

Once you have cut the fungus and mushrooms, throw them into the still simmering soup, along with your drained and rinsed bamboo shoots. I buy these already shredded.

Taste your soup broth and see how flavorful it is. If you want it to develop more flavor, you can cook it, covered, for another hour. Or you can add more wine. Or more pepper. Whatever you like.

After the soup broth has gotten a flavor you like, gently add the tofu. Now, when you stir the soup, do it carefully to keep the tofu from breaking apart.

Bring the soup to a boil, and start stirring it steadily clockwise. Pour the eggs into the soup in a very thin stream and watch them form little clouds in the broth. These are poetically called egg flowers. They do look like delicate flower petals.

At this point, season your soup to taste with dark soy sauce (I usually add about a tablespoon or so of it)and chile garlic paste, if you want more chile heat. I prefer to let the black pepper dominate, so I use little chile paste.

While the soup is still boiling, add a cornstarch slurry to thicken it. As soon as it thickens as much as you like, take it off the heat so you can finish the seasoning and garnishing. I don’t like my soup to be really gloppy thick, nor do I like there to be cornstarch boogers in the soup, where when the soup was being thickened, no one was stirring and a big lump of cornstarch formed a scary loogy thing. Ick. I generally use very little cornstarch, just so it barely thickens enough to coat a spoon with a thin layer.

Off the heat, add the vinegars–I use half white and half black vinegar–the black is sweeter, so it adds yet another flavor nuance to the soup. You can use one or the other or both. But whatever you do, add it off of the heat. If you add it while the soup is simmering or boiling it will boil away–vinegar boils at a lower heat than water so you will lose the sour flavor if you add it any earlier. Also, if you heat up leftover soup to a boil, remember to add more vinegar after it is hot, or you will not have the sour flavor anymore.

Also, how sour is a matter of preference. I like mine pretty sour, but I know other people like it a bit more subtle. Hence the lack of a definate amount on the vinegars. What I like may not be what you like.

Finally, add the sesame oil, and sprinkle on the cilantro and the scallion tops.

The finished soup, garnished and ready to serve.

The Chinese Cookbook Project IV: From the Best Chinese Restaurant in the World

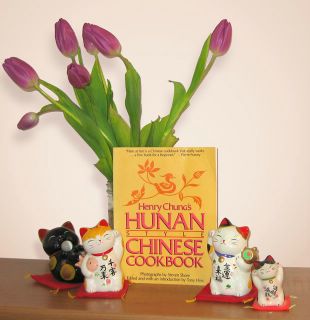

One of the few cookbooks featuring the cuisine of Hunan province, Henry Chung’s Hunan Style Chinese Cookbook is sadly out of print.

In 1974, Tony Hiss, a staff writer for The New Yorker Magazine, dubbed Henry’s Hunan Restaurant on Kearny Street in San Francisco’s Chinatown, “the best Chinese restaurant in the world.” Thirty-two years later, though the original tiny thirty-six seat establishment is long gone, four other branches of Henry’s Hunan are still family owned and operated and going strong, with a huge following of San Francisco natives and tourists. Their dishes are still considered to be among the most authentic and flavorful Hunanese foods available anywhere in the world, and people are still eating and raving about farmhouse classics such as Harvest Pork and Smoked Ham.

In 1974, few people may have ever heard of Hunanese cuisine, but in 2005, an informal survey of Chinese restaurants in the US reveals that Hunan cooking is one of the most popular of the Chinese regional styles, with many restaurants using Hunan in their names. Even if a restaurant’s typical style is Cantonese, there is bound to be at least one or two classical Hunan dishes on the menu to satisfy customers who like fiery dishes.

Oddly, though Hunan cookery is very popular among eaters in the United States, there are few cookbooks available to help intrepid cooks replicate these flavors at home. The closest many home cooks can come to finding Hunanese recipes in print are recipes sprinkled hither and yon throughout many general Chinese cookbooks.

The only cookbooks to feature Hunanese cookery exclusively seem to be out of print. (I have heard it rumored that Fuchsia Dunlop, author of the seminal Sichuan cookbook, Land of Plenty, is currently researching a similar work on the food of Hunan province; I hope this rumor is true, as there is a real dearth of documentation in English of Hunanese food.) Of the three of them I own, the best is unsurprisingly, Henry Chung’s Hunan Style Chinese Cookbook.

An unpretentious little volume, with a glowing introduction by Tony Hiss, photographs by Steven Shore and an amazing amount of historical and cultural information, Henry Chung’s cookbook is a powerhouse of authentic Hunan recipes. Many of the dishes for which his restaurants are justly famous are featured within these pages, but there are many other great recipes on offer as well, including a delicious sounding chicken, ham and mushroom soup which Chung claims was given to women to help them recuperate after childbirth.

The story behind each dish is outlined before the recipe, and each chapter is illuminated by personal remembrances of Chung’s years growing up. He paints a vivid portrait of his grandmother, who he declares was the dominant personality in his family and who taught him everything he knew about cooking. A devout Buddhist, Chung’s grandmother was also well known as a great cook and a very generous, loving person. She apparently treated all beings with honor and respect, from Chung’s childhood dog (when he died, she gave the dog a Buddhist ceremony in order that he might reincarnate as a man in the next life) to beggars to family and friends. From her, Chung says he learned not only how to be a great cook, but how to be a good person.

Hunan province is apparently well known for its folklore, and Chung includes a few pages of folk traditions regarding marriage, cooking, Feng Shui and one interesting entry called, “How to Model a Baby Before Its Coming into Being.” Here, Chung lists traditional advice about how to go about the peril-fraught business of conceiving a healthy, lucky child.

The recipes are all well-written, with a lot of advice on substitutions and clear photographic illustrations for the complete beginner. General instructions on how to improvise a steamer, how to handle Chinese cooking utensils and how to cut ingredients uniformly are also written and illustrated in a clear, concise fashion.

Since Chung claims Kung Pao Chicken as a Hunanese dish in the book, I decided to try his recipe for it. However, as I had no chicken and instead had beef, I used his recipe for Kung Pao Thin-Sliced Beef with Roasted Peanuts.

I did change two things about the recipe. One, he had the cook deep fry the beef in two cups of oil, then drain away all but a few tablespoons in order to stir fry the rest of the dish. Not only is this a messy prospect, I don’t like adding a million and a half calories to my dinner from deep frying it when I could just as easily and flavorfully stir fry it from the beginning. So, out went the two cups of oil before I even started cooking.

Also, his recipe called for one cup of canned sliced bamboo shoots, or one cup of sliced carrots or one cup of sliced asparagus. As I had fresh water chestnuts, gai lan and carrots, I used all three instead.

However, the seasonings and general directions are the same as they appear in the Chung book.

Henry Chung’s Kung Pao Thin-Sliced Beef with Roasted Peanuts

(The original text is in brown, my substitutions are in green.)

Ingredients:

1/2 pound flank steak, cut across the grain into pieces about 1/8″ thick and 1″ long

1 egg white or 1/2 tablespoon cornstarch (I went with the cornstarch, as I was nearly out of eggs)

1/2 tablespoon white wine (grape wine is rare in China, I substituted white rice wine)

2 cups vegetable oil (I used 3 tablespoons peanut oil)

5 whole dried hot red peppers

1 cup canned sliced bamboo shoots (I used a total of 1 1/2 cups of vegetables, made up of fresh water chestnuts peeled and sliced into rectangles, 4 stalks of gai lan, cut on the bias 1″ long, and baby carrots, cut on the bias)

1 teaspoon hot red pepper powder, or 1 teaspoon hot red pepper sauce or hot pepper oil (I used my own homemade hot pepper oil with the seeds included)

1 tablespoon fresh garlic, minced, optional (garlic is never optional at my house)

2 tablespoons soy sauce

1 tablespoon white wine (again, this was substituted with rice wine)

1/4 tablespoon sugar, optional (I left that out, but should have put it in)

2 scallions, both green and white parts, cut into 1 1/2″ long pieces

pinch salt

1/2 cup roasted peanuts, crispy and fresh (I used unsalted dry roasted peanuts)

1/2 teaspoon sesame oil, optional (I bet you will not be surprised to hear that sesame oil is not optional in my kitchen, either)

Method:

Mix the beef with the marinade, and allow to stand for five minutes.

Heat a wok over highest heat for 2 minutes; add vegetable oil. As soon as oil is smoking hot, vigorously stir-fry the beef pieces for 5- 10 seconds only. Do not cook longer. Remove beef to a strainer to allow oil to drain off. (I would use a wire skimmer to do this if I were going to do it and put it on a platter lined with layers of paper towels to absorb the oil. If I were to do this, which I am not likely to.)

Pour all but 2 or 3 tablespoons of oil from wok and heat until smoking hot. Fry the hot red peppers until dark brown, about five seconds. Add bamboo shoots, hot red pepper powder, and garlic, stir fry for 1 minute. (Okay, here is where I changed the recipe the most. I skipped the deep frying part entirely, and went to the 2-3 tablespoons of oil business. I fried the chiles until dark brown, then added the meat, the chile oil and stir fried until the meat was brown, then added the garlic, and kept frying. Then, I added the vegetables, all at once; I had cut them so that they would cook at the same time, approximately.)

Return beef to wok and add soy sauce, wine sugar, scallions, salt and roasted peanuts. Stir fry vigorously until thoroughly blended and hot for about ten seconds. Remove to serving plate and garnish with sesame oil. Serve with steamed rice. (Okay, after I added the vegetables, I added the soy sauce–I used Kimlan Aged Soy Sauce–wine, scallions, salt and peanuts. And I stirred until it all came together and was done.)

Kung Pao Beef from a recipe I found in Henry Chung’s Hunan Style Chinese Cookbook.

My feeling, and Zak’s, was that it was good, but not quite spicy enough, leading me to believe that the quantities of chile called for in the book as written was scaled down for American tastes. Which is fine; it just helps to know that when you are cooking from it. If I were to do this recipe again, I would at least double the amount of chile oil, and I might add fresh chile peppers to it.

I think on the whole, that while this was a perfectly good rendition, I prefer the Sichuan take on Kung Pao, which includes Sichuan peppercorns and ginger, as well as the ingredients featured in the Hunan version. I prefer the more complex flavors featured in Sichuan cookery, and I like the wild interplay of various ingredients that set the tongue ablaze.

I will try some other recipes in this book at a later date, and when I do, I will post about them–several of them sound delectable. I just happened to have the ingredients for Kung Pao on hand and was curious to try Chung’s version and compare it to the way I make it which is a distillation from my experiences tasting the dish made by various chefs and my experimentation with many recipes I have tried over the years.

I am especially eager to try Harvest Pork and Stir-Fried Duck with Bitter Melon, which Chung claims is a very local dish served only in his home county of Li-ling in Hunan. I will have to give it a shot in the summer, as Chung notes that both bitter melon and duck are cooling.

It Isn’t Just About the Crunch

Fresh water chestnuts on a plate with gai lan, or Chinese flowering broccoli.

If you haven’t figured it out by now, I love shopping in Asian markets, particularly ones with well-stocked produce sections. Not only do they have innumerable types and varieties of greens for sale, but they also have many other delicious vegetables which many Americans have never tasted.

Such as fresh water chestnuts.

People who have never had a fresh water chestnut think that the entire purpose for the existence of them is to be crunchy, and sort of juicy. They think of them as pallid, flavorless little nuggets that come in cans, packed in tinny water which are added to various Chinese foods just to give them a jolt of crispness.

But that isn’t it at all that there is to them.

Water chestnuts are not a one-dimensional vegetable.

In their natural, uncanned state, they are delicious. Not only are they crisper than the canned sort, and juicier, they are intensely sweet. Uncooked, they taste sweeter than some varieties of apple, and stir fried, they are sublime, with a toothsome crunch and a subtle nutlike flavor.

Whenever I can get my hands on them, I buy them up and use them in whatever dish I am cooking, and when I teach Chinese cookery, I always try to have fresh water chestnuts on hand so that my students can taste the huge difference they make in foods. When I cannot get them, I substitute for them with jicama, a South American tuber that has a nearly identical texture, and a similar, though slightly starchier flavor.

I will no longer use canned water chestnuts, except under duress.

I lucked out this afternoon and found not only Thai basil, and Chinese flowering broccoli (gai lan) and beautiful pea shoots at the Chinese grocery, but also some fresh water chestnuts. Snagging up about a dozen of them, I tucked them gleefully in my shopping cart next to the Shanghai bok choy and skipped off down the aisle, my mind racing as I determined what to do with them.

I decided to use them in a version of kung pao beef with the gai lan and some carrots. The dish turned out looking very beautiful, with the jewel tones of the vegetables contrasting perfectly with the richly browned beef.

Kung Pao Beef from a recipe I found in Henry Chung’s Hunan Style Chinese Cookbook. The only thing I changed was the amount and type of vegetables used in the dish.

In order to pick out good water chestnuts, it helps if you can touch and smell them. They should either have little scent, or smell of the rich dark mud they grew in. If they are sold coated in mud, that is good–it helps to keep them fresh. The market where I buy them washes them thoroughly and packs them in little trays under plastic wrap. In that case, I poke at them and make certain they are quite firm and unyielding to the touch, and their skins are shiny, with some papery bits that are duller. There should be no evidence of mold or sliminess to water chestnuts at all.

Once you have them home, if they are muddy, give them a good soak in several changes of water, and then a gentle scrub with a vegetable brush to get all of the silt off of them. Then, using a very sharp paring knife, cut off the top and bottom, where the shoots and root ends are, and then carefully remove the peel in concentric circles. Work as slowly as you need to, so as to minimize wasting the flesh of the water chestnut by cutting too deeply.

After they are peeled, rinse them one more time and then you may cut them in whatever shapes you like. Have a taste of one before you use it to cook with, though I warn you–you will be tempted to keep eating them they are so good. But don’t do that–you would be very, very sad if you didn’t leave enough to put into Meyer Lemon Chicken or Chicken with Garlic Sauce or whatever other dish you feel like using them in.

I store the unused ones, still in their peels, in a paper bag in the fridge in the dry crisper drawer, not the humid one. They keep for up to a week, if they were really fresh to start out with. They don’t freeze well, but they do make tasty snacks, so if you find yourself unable to think of something else to put them in, slice them up and put them in salads, or just peel and eat them.

It will never do to waste a perfectly beautiful food like a fresh water chestnut.

I Bet You Didn’t Know That Shiksas Had Balls….

The finished soup, ready to go forth and heal the sick. I have never seen it raise the dead, though it has come close.

I will be the first to admit that most shiksas do not have balls. But this one does.

Of course, this entire discussion is predicated upon the reader knowing what the hell a shiksa is. “Shiksa” is an uncomplimentary Yiddish term for a female gentile. I, being not Jewish, could be called a shiksa, though it wouldn’t be very nice to do so. All of my Jewish friends and relations assure me that I am not a shiksa.

The problem is, I like the -sound- of the word, and enjoy saying it. “Shiksa.” It is just fun to say. Say it with me. “Shiksa.” I like to draw out the “sh,” and then append the “iksa” in a quick perfunctory fashion. One of the greatest words of all time.

Now, knowing as we do that a shiksa refers to the female of the species, why would she be endowed with anything resembling balls?

Well, I am not referring to that kind of balls. I am actually referring to matzo balls.

Matzo balls are dumplings made out of matzo meal, which is ground up matzo. Matzo, for those who are not knowledgable about such things, is the crisp unleavened bread that is eaten during Passover in remembrance of the exodus from Egypt, when the Jewish people had no time to leaven their bread, so they made flat breads.

Matzo balls are usually served in a very rich chicken stock, which may or may not have noodles in it in addition to the balls. Sometimes there are shreds of chicken. A sprinkling of herbs is nice, but it is a fairly simple soup.

It is the soup that Bubbes (Jewish Grandmas) make when kids and grandkids get sick. And it is a supreme comfort food, indeed.

Well, that is great, but I like soups that eat like a meal, so the first time I made matzoh ball soup, I added an entire farmer’s market worth of vegetables. Leeks, garlic, carrots, mushrooms and potatoes all found their way into the soup, along with the chicken and the matzoh balls. In fact, I changed the dish so much, I felt the need to rename it. Having a sick sense of humor, I called it Shiksa Ball Soup. Zak and his family all think it is a cute name, so it stuck.

To this day, it is what Zak wants when he is sick, unless he wants Hong Kong style Barbeque Pork Noodle Soup, in which case, I make that for him, though it is infinately more complicated, involving a pork and chicken stock and Chinese barbeque pork.

When I was a personal chef in Baltimore, several of my clients were Jewish. I was booked for Passover every year by a wonderful woman who grew up in Russia, and who was a most delightful cook herself. She would have me help her cook for the sedar, which is the ritual Passover meal, because it was a lot of company and she getting up in years and wanted to be able to enjoy the dinner and ceremony. So, I would come and help with the main course, and once she saw I knew how to make matzoh ball soup, I would make that, though I would stick to the traditions and not “shiksa up” the recipe. She laughed when I told her about my version and what I called it, though she assured me that I was no shiksa.

I would serve the dinner, but hang out in the kitchen, watching the food. Her husband, who conducted the service, had the most beautiful tenor voice, and he chanted many parts of the Hebrew. The melody would soar and dip like a bird in flight and I would hover near the door, listening.

When they found out I was listening, they made a place at the table and insisted I sit with them. They had assumed that since I was a gentile, I would not be interested. So, I sat with them, and celebrated with them. At one point while we were eating, one of the guests pointed to the empty place set at the table near the open dining room door. “Why is it we always set an empty place at Passover?” the woman, who was indeed Jewish, asked.

Before I could check myself, I said, “It is for Elijah. That is why the door is open, too.”

Everyone looked at me with surprise, and the host smiled. “Yes, yes, you are right!” he exclaimed and then went on to explain the tradition of leaving a place for the prophet Elijah to his guest. I blushed and was silent, but my client, as we cleared the plates said that I shouldn’t be embarrassed to know so much.

“It was her who should have known and didn’t who should be embarrassed.”

So we served the next course, and all was well, though I felt very shiksa-awkward for a while after that.

Let us fast-forward to yesterday evening. We were supposed to be flying to Tucson for vacation. Instead, Zak was abed, sick with the flu, and I was in the kitchen, cooking shiksa ball soup, and praying that the touch of the flu I had didn’t develop into a full-blown case of it. (So far, so good.)

Since I had the flu, I did not start with a whole chicken carcass. I cheated and started with chicken broth, because I was too tired to roast bones and skim scum off the top of a stockpot. Besides, Zak needed healing, pronto, so I needed to make soup in a couple of hours, not in a process that takes all day.

But there is so much other good stuff in there, and I made the shiksa balls from scratch, so hey–it turned out to be quite flavorful. When next I have a whole chicken to work with, then, I shall make shiksa ball soup slowly and traditionally, rather than using my fast, cheater’s method.

But, as I said, I am breaking tradition all over the place in this soup, so why not?

Also, I used leeks in the soup. I love leeks in soups and stews; if you slice them very finely they eventually break down into the broth, giving it body and a most delicious flavor. However, there is a problem when it comes to leeks. They are filthy. Fine black grit gets in between the layers that make up the leek stalk, so I advocate rinsing them, cutting off the root ends, splitting them in half, and then rinsing them again. And then, I slice them thinly and stick them in a big bowl and rinse them again, letting them soak a bit this time. I swish them around in the water with my hand, and then lift them out of the water–if you pour them into a colander and let the water wash over them, all the grit just gets back on them. And gritty soup sucks, let me tell you. After lifting them out of the water, pouring out the bowl and rinsing it, I repeat the bowl treatment at least two more times.

Notice the dirt caught between the layers of the leeks. This is why I advocate cutting the leeks up and then rinsing them in at least three changes of water.

Leeks are a pain in the tuchus, but they taste really good, so it is worth it.

You will also note the presence of dried shiitake mushrooms and a dash of soy sauce in this soup. I generally explain this by commenting on the Jewish people who wandered off and ended up in China (apparently, several of the lost tribes did this a long time ago–I used to joke about this as an explanation as to why Jewish folks love Chinese food so much, but I recently read an article by a scholarly rabbi documenting just such a historical occurance, so I guess I won’t joke about it any more), but the truth of the matter is that both add a great amount of flavor to the soup, so that is why they are there.

I also add turmeric, not only for the rich yellow color it imparts to the broth, but also for the subtle flavor it gives the soup.

Here is the recipe as I made it last night:

Shiksa Ball Soup

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons olive oil

4 large leeks, sliced thinly and washed at least three times, then drained

5 cloves garlic, minced

2 tablespoons fresh rosemary, minced

1 teaspoon dried thyme

1/4 teaspoon dried sage

1/2 teaspoon crushed celery seed

1/2 teaspoon turmeric

2 bay leaves

black pepper to taste

1/4 cup sherry or dry white wine

3 quarts chicken broth

2 cups vegetable broth

1/2 pound baby red potatoes, scrubbed and cut into eighths

1/2 pound baby carrots

2 dried shiitake mushrooms, soaked

1 tablespoon aged soy sauce or tamari soy sauce

1 1/2 boneless skinless chicken breasts, diced

2 eggs, well beaten

2 tablespoons olive oil

1/2 cup matzo meal

1/4 teaspoon salt

seasoning to taste (I used Penzey’s Fox Point and Northwoods Seasonings and a dash of dried chipotle chile powder)

2 tablespoons chicken broth

2 small turnips, peeled and diced finely

Ingredients for shiksa ball soup, the fast method.

Method:

Heat olive oil in a heavy-bottomed, deep soup or stock pot. Add washed, drained leeks to the oil, and saute until they just begin to turn golden and shrink a bit. Add garlic, herbs and spices, and continue cooking until the leeks begin to brown on the edges, then add sherry or white wine and allow alcohol to boil off.

Here, the leeks, garlic, and herbs are cooked in olive oil a bit in order to make a flavor base for the soup. Eventually, the leek slices will disintigrate into the broth, giving it body and wonderful flavor.

Add chicken and vegetable broth. Add potatoes and carrots, and bring to a boil, then turn down to a simmer.

Take shiitake out of the soaking water and squeeze out the excess water. Cut off stems and discard, then cut the mushroom caps into a dice. Add to the pot, along with the soaking liquid. Allow soup to cook while you prepare shiksa balls.

Dried shiitake mushrooms before being soaked.

Beat eggs, oil, salt and seasoning together until well combined. Add matzo meal and stir to combine. Add broth and stir well. Cover loosely with plastic wrap and let mixture sit in the refrigerator for fifteen minutes.

When the potatoes are tender and done, take out shiksa ball mixture. Add diced chicken to the soup, and bring to a boil, then turn down to an active simmer.

Using a small cookie scoop or a tablespoon, scoop up mixture and form into balls. Drop into simmering soup and cover with lid. Set timer for fifteen minutes.

Using a cookie scoop makes the making of matzoh balls a less messy and somewhat simpler process.

After fifteen minutes, add turnips, put lid on pot and set timer for fifteen more minutes.

When timer goes off, the shiksa balls should be done, and the soup is ready to serve.

Unlike most people, I cook the matzo balls in the soup itself, because I like the soup flavor to get into the dumplings. Also, why dirty two pots?

Okay, a few more words about matzo, or shiksa balls.

There are two kinds of them–dense ones that Zak kindly refers to as “neutronium balls” and light fluffy ones which I call “fluffbunny balls.” He prefers the former, which is what my recipe will make. If you want the lighter ones, there are a couple of things you can do. One, is you can get Manischewitz Matzo Ball Mix and follow the directions on the package. When I do that, they turn out light and fluffy. I suspect that the bicarbonate of soda that is in the mix is what does the trick.

If you follow my recipe, they will be heavier, though not leaden. Leaden shiksa balls would be nasty indeed, and would probably not heal anyone or anything.

The Power of Plastik Cheez

I just read an article I found linked on Saute Wednesday written by John T. Edge about how he learned all about Tex Mex food from Robb Walsh, author of The Tex-Mex Cookbook: A History in Recipes and Photos. It reminded me of me learning how to cook Tex-Mex food, and an altercation I had with a friend over the use of Velveeta, or what Walsh calls, “performance cheese” (is that like performance art?) in it.

But before I get to that, I am going have to ‘fess up to something right here. Culinary snobs can stick thier noses right up in the air at this confession, but that is okay. It isn’t the first time I have had to look up someone’s nostrils. (Remember, when you stick your nose up, those of us shorter than you can see your nostril hair. Think about that the next time you are feeling high and mighty and you might lower that nose and be a bit more humble. I know it works for me. I don’t want to subject folks to visions of the contents of my nostrils–I know what evil lurks up there. I wouldn’t want to strike someone blind, cause their hair to go white or make them run away, gibbering in horror.)

My confession: I was raised eating Velveeta.

I know. It makes me shudder to think of it, too, now. Take a deep breath, and keep breathing, and read on. It gets worse.

That was the everyday cheese in our house. Mild longhorn cheddar was a frequent guest, though I never much cared for it–my mother loved it. Everything else, and there were quite a few everything elses, as Mom, Dad and I all three love cheese, was a special treat bought for an occasion. Like the Edam and Gouda which we got every Christmas, or the super extra special New York or Vermont sharp cheddar we’d get for my birthday because it was my favorite.

I used to get cheese in my Easter basket, so, you see, real cheese was for holidays.

For all other days, there was the Nucular Orange Bricks of Plastik Cheez which went in my grilled cheese sammitches. Sammitches which were always served with some Campbell’s Cream of Tomato soup. Dipping the sammies in the soup was way tasty.

Mom used it to make cheese sauce. She’d melt it down with a bit of milk to thin it, some salt and some pepper, and there it was. Cheez sauce. That was nearly always poured over well-boiled cauliflower. It was quite tasty, too, though now I tend to not like my cauliflower so mushy.

My Gram and Grandma used it too, and they were both phenomenal cooks.

But they loved the Velveeta.

It is a cultural thing, though I know some would say it is the opposite. Instead of being a signifier of a culture, this love of Velveeta would be a symptom of a lack of cultural values, but be that as it may, I grew up in West Virginia. Cheese in West Virginia means Velveeta or Kraft Singles. Unless, of course, you didn’t have much money, in which case, cheese was government surplus processed cheez that was even wierder, gummier, and rubberier than Velveeta could ever dream of being.

I don’t know why. I can’t explain it. But the hillbillies love the Velveeta, and it is an ingredient in nearly every damned casserole, sammitch, soup and entree that it can be somehow fitted into. I even know of someone who used it in fudge. (I know, the thought of it horrifies me, too. I get queasy just thinking about it. And no, I have never tasted it, so I cannot tell you how horrible it is.)

Now, I have been to culinary school. I know how to make a right and proper mornay sauce (that is cheese sauce for those of you who don’t parlez the Francaise), and I will walk ten miles barefoot in the snow uphill to get some good goat cheese. (As you can see in the picture below, I could go outside right now and demonstrate that for you, but I don’t love y’all enough. You are just gonna have to take my word on my love for the chevre.)

That is my deck. There are stairs under that three and a half feet of snow piled up in graceful peaks and valleys there, though I think that in reality only six to eight inches have fallen. The wind is blowing madly, making huge drifts covering not the yard, where I do not have to shovel, but the deck. All this on the first day of March. And no, I ain’t walkin’ barefoot in that to prove my love of goat cheese to no one nor their cousin.

Brie en croute–I am so there. Gorgonzola sauce over pasta with walnuts and rapini–my mouth waters to just think of it, even though I am allergic to the blue-veined cheeses and pay for indulging with many hours of pain and suffering afterwards. Stinky raclette melted over boiled baby potatoes with some snappy sour cornichon is heaven. And silken French cheesecake is my number one favorite thing in all the world.

But, oddly, I used to find myself craving that damned Plastic Cheez now and again. I am reformed on this point. I am allergic to American Processed Cheez Food, and have been for years, but I used to like it so much, I’d eat it anyone and suffer. Now, the suffering outweighs the enjoyment and just thinking about the stuff makes my innards do an unpleasant serpentine dance that might be inviting were it happening with a pretty lady in filmy draperies on stage rather than inside my guts where the appeal is distinctly lacking.

However, in the past, I used to crave the stuff, even though I knew better.

I’d to fight the cravings. I’d resist. I’d ignore my desires, and run past the yellow boxes of processed cheese food in the store. I took to making my grilled cheese sandwiches with Muenster cheese and sliced heirloom tomatoes.

But I would dream of the melty-gooey orange glop of Velveeta.

A friend of mine from Texas used to love to go eat at Don Pablo’s, because it reminded her of home. She’d scarf down half of a bowl of their chile con queso in a flash, and I would finish the rest, because it was bubbling liquid gold–processed cheese mixed with salsa and melted into a lava-like consistency that went really well on salty tortilla chips.

Now this friend and I used to say, “Texas and West Virginia are two states separated at the birth of a nation,” because she and I had such a good understanding of all things redneck, white trash and hillbilly, though she also was versed in the Cajun, which I did not know. It was our upbringing which we felt gave us a kinship under the skin. And one place we always got on well was the kitchen, both of us being mavens of the Southern food stuck among a bunch of Yankees who didn’t know how to cook a damned thing.

So, when she convinced me to take up cooking Tex Mex for her, I broke down and bought some of the Velveeta, and used it to make the chile con queso. She came over and saw the Velveeta package and put her hands on her hips and said in a drawling bellow, “I do -no-t believe what I am seein’! I do not believe it! Why I declare, there is a chef standing in her kitchen melting plastik cheez! I never heard the like!” She shook her head. “You are revertin’ to your hillbilly nature.”

There is just no pleasing some people.

I looked up at her and narrowed my eyes. When I am around folks with pronounced Southern accents, mine starts to come out. Normally, I keep it in check, but when around other Southerners, out it comes. When I am riled, it is doubly apt to make an appearance. I composed myself and managed to avoid the temptation to call her an “ignorant cracker.”

“Aw, dammit,” I snapped. “You said you wanted Tex Mex. Well, it is made with Velveeta, I will have you know, and I was gonna use sharp cheddar and jack cheese, but I knew if I did, you’d tell me it didn’t taste right.” I resisted the urge to add, “Ya dumb nouveau-riche redneck.”

“We don’t use Velveeta at home,” she folded her arms and tossed her wild curls. “Nuh, uh–it is jack and cheddar all the way.”

“You can’t get jack and cheddar to melt to that smooth texture that Velveeta has.” I went back to stirring, lest I fling the wooden spoon and bean her right between her eyes.

“Be that as it may, that is what we use.” She stuck her nose up, and I saw her nostril hair.

“You need to blow your nose,” I commented as I scraped the queso into a heated dipping bowl and shoved it at her.

She dipped a chip in and said, “Hey, this tastes just like Don Pablo’s!”

“There is a reason for that,”I commented dryly as I bent over to pull out the enchiladas, which I admit, were made with a mixture of cheddar, jack and Velveeta.

“Well,” she said as she started dipping her fingers in the cheese and licking it off, “well, I reckon maybe–maybe it ain’t just hillbillies that use this stuff after all.”

Pacified, I served her the enchiladas, and watched her eat two plates full.

She never gave me crap about the nuclear orange cheez again.

There is no moral to the story, except, eat what you like, even if it is white trash food. And don’t apologize to anyone about it.

And don’t call your friends things like “ignorant cracker” or “dumb nouveau-riche redneck,” even if you think they deserve it, and even, or maybe especially, if they provoke your temper.

It ain’t nice.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.