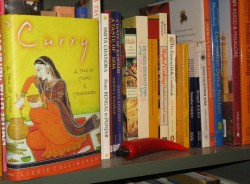

Book Review: Curry

I started reading Lizzie Collingham’s book, Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, last week, and finished it within a few days. It is a fascinating little book, filled with historical details and thought-provoking ideas, the most revolutionary of which is that curry, as a dish, has gone beyond its origin in India, and has in fact, become an international dish that means different things to different people.

Contrary to the blurb written by Oxford University Press, the publisher of the book, it is not the definitive history of Indian food. For that, we must turn to K.T. Achaya’s Indian Food: A Historical Companion. While it is sadly out of print, Achaya’s book still stands as the best history ever written about Indian food from the ancient to the modern worlds, filled with scholarly details and careful documentation.

Curry is a very different book, and I think one that is more limited in scope. Rather than give a comprehensive history of the totality of Indian cuisine as Achaya has done, Collingham explores various feelings many Westerners have about Indian food in general, and restaurant foods in specific. In the process, she explodes many myths and mistaken beliefs that Westerners hold about curry.

For those British folk who grew up eating curries, (or as they say in the UK, “having an Indian,”) it might come as a shock that many of what they think of as “authentic” Indian dishes are no such thing, but instead, were restaurant innovations that sprang from the need to make shortcuts in the cookery, or to adapt it to Western palates. Chicken tikka masala, for example, was a dish created in the restaurant trade after bringing the tandoor oven to Britain. It is said that a customer complained that the chicken breast bits cooked in the Punjabi style on skewers in the molten heat of the clay oven was “too dry,” so an enterprising chef concocted a cream and tomato-based sauce to go with it.

In 2001, chicken tikka masala was named as the new “national dish of Great Britain,” which caused a flurry of derisive commentary from food journalists who declared that chicken tikka masala couldn’t even be called authentic Indian food.

But isn’t the point that it is a national dish of Great Britain, not India, one could ask–and Collingham does.

This question, this essential tension between curry as it is cooked by Indians for themselves (in which case, it originally would likely not be called “curry” in the first place–it is a word that was coined by the British to describe the unfamiliar braises, stews and spiced fried dishes they found being cooked in India under a dizzying array of names), and curry as it is cooked by them for others in restaurants, or by others, is part of the central theme of the book. “What is authentic Indian food?” Collingham seems to be asking, before she adds, “and is it called curry?”

The answer that she provides is multi-layered, just as the history of the food of India is complex and multi-faceted. She correctly points out that while the very similar menus of Indian restaurants on both sides of the Atlantic seem to point to a single national cuisine of India, there is no such thing. India is a vast country, with very different microclimates and agricultural traditions that vary from region to region. These purely physical environmental differences alone have helped steer India towards having very disparate regional cuisines, but once the different religious and cultural dietary restrictions are added into the equation, the stage is set for it to become impossible for there to be one single over-arching cuisine.

As far as I am concerned, that is a good thing. I am all for diversity at the table, and I, like Collingham, believe it is important for food to reflect the heart and souls of the people who cook and eat it. Whether they are Hindu, Muslim, Parsee, Buddhist, Jain, Christian or Jew, food traditions are important components of cultural identity, and should not become homogenized into a polyglot that loses the power of its meaning.

So why do Americans and the British have this idea that “Indian” food is that which is reflected in the menus of their local restaurants? Collingham answers that in part, it has to do with the fact that most Indian restuarants in those countries are owned by Pakistani and Bangladeshi people, who bring their own northern Indian cooking traditions to the restaurant-going public, but it also has to do with the tradition of feeding the dishes of the Mogul Emperors to the British during thier occupation of India during the Raj period.

These very rich, primarily Persian-Indian fusion dishes, were developed in the royal courts of the Persian Mogul Empire which began with Babur’s conquest of Hindustan, as Northern India was called at that time, in 1526. Combining the Persian predilictions for using fruits, dairy products and nuts in savory, meat-laden dishes, with the Indian knowledge of spices, the use of dals and the principles of Auyervedic cookery, Mogul cuisine is rich, and filled with a complex parade of dishes meant to satisfy the rarefied palates of the emperors and their courtiers. It is only natural that elements of this cuisine was bequeathed to the kitchens of the British Raj, as local cooks and servants treated the “sahibs” and “memsahibs” as royalty.

Eventually, versions of these dishes, such as biryanis, kormas and pillaus ended up on the menus of Indian restaurants in the West, as they had already been proven to appeal to Western palates. Even the titles of many of these dishes as presented in the West harken back to the days of the Mogul Empire: “Navrattan,” which means “nine jewels,” refers to the nine most beloved courtiers of Emperor Akbar’s court, while “Shajahani biryani” refers to a biryani that was named for Akbar’s son, Shajahan, the builder of the great Taj Mahal.

The greatest theme that Collingham brings forth in her work is that of culinary change. As you read Curry, you come away with the understanding that no cuisine exists in a vacuum, and no cuisine is static. There is always change, adaptation, and development. There are always new ingredients, new political or social circumstances, new foodstuffs and new technology to be incorporated into the kitchen. These novelties ensure that no cuisine ever remains static, and instead is in a constant state of flux, which is, as far as I am concerned, the sign of a healthy living system.

Nothing in nature stays the same for long–all things grow and change or are left behind in the dust of history.

Why should cookery be any different?

In the end, Collingham’s view is that curry means different things to different people. Now that it has travelled beyond the borders of India, it has become popular in Japan, the West Indies, the UK, and the United States, and each country to which it travels, changes it to some extent. Curry powder has become integral to several Chinese dishes, and the tradition of Thai curry making is the result of trade and cultural exchange along the silk road between India and China through Thailand.

Curry is rooted in India, but has become a citizen of a global world, and has become a beloved part of many dinner tables among many peoples. In this way, I would say, that no matter how much India’s cuisines were changed by trade, invasion and occupation, tthe spices of India did just as much to enrich and enliven countless cuisines of the world.

And I think that Collingham would agree.

The First Indian Food I Ever Made: Rogan Josht

Long, long ago, before I had married Morganna’s father, and before I had even heard of anyone named Zak, I was still a curious cook.

My curiosity was curtailed, however, by several factors: one, I was poor and could seldom afford interesting ingredients, two, Morganna’s father was not a very adventurous eater and I lived with him, and three, even if I could afford ingredients, I lived in a place where they were hard, to downright impossible to find–Huntington, West Virginia. (This was twenty years or more ago–it is possible that by now, they have a decent Middle-Eastern, Chinese or Indian market. I doubt it, though.)

While these limiting factors slowed me down, they did not stop me. Not by a long shot.

I still read cookbooks voraciously, and while I was not allowed to touch the wok (I was supposedly incapable of using it properly–whatever), and so had stopped trying to cook Chinese food, I was still fascinated by Indian food.

I don’t know why, really. I know that I had, from childhood, been equally fascinated with China, Japan and India, and had always yearned to visit. I read all I could find about India as a little girl, and I very much admired Ghandi–the man who peacefully stood down the might of an empire. I learned about the many religions that coexist in India: the many types of Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Jainism, Sikhism, and Zoarastrianism, as well as Christianity judaism. It was, in fact, after exploring these religions, that I quite pointedly told my Sunday School teacher that I could not imagine that God meant only Christians to go to heaven, as I imagined God’s heart would be much bigger and less–petty than that. That was one of the first times I had the guts to speak aloud my belief that God didn’t play favorites with people, and that good people went to heaven, period: Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Jews, Buddhists–God loved us all.

Needless to say, this started quite a stir in the class, and some of the kids took to calling me “heathen,” but even the teacher was stunned into silence when I declared that I could not and would not worship a God who would throw so moral and peaceful a man as Ghandi into hell for all eternity just because he wasn’t Christian.

So, now you know–I grew up a blasphemer. Oh, well. There are worse flaws to have than a logical mind which is not dazzled by religious dogma. (My mother sighed at these antics, but my father always chuckled. I think that secretly, he was proud of me.)

Be that as it may, through my entire life, I wanted to taste Indian food. (Which struck my parents and friends as odd, because I had a strong aversion to dishes that people made and called “curry” that involved apples, black raisins, sweetened dried coconut, curry powder and lots of onions. These “curries” always smelled awful to me and tasted worse. The only thing I liked curry powder in was scrambled eggs–a pinch of it perked them right up.)

However, as there was no Indian restaurant to be had in Charleston or Huntington at the time, there was no opportunity.

So, I read cookbooks, and experienced it vicariously.

Until I read Madhur Jaffrey’s description of Rogan Josh in her book, Madhur Jaffrey’s Indian Cooking. “Rogan Josh gets its name from its rich, red appearance. The red appearance in turn, is derived from ground red chillies, which are used quite generously in this recipe. If you want your dish to have the right color and not be very hot, combine paprika with cayenne pepper in any propirtion you like…”

Yes, it was the chiles that did it for me. The chiles and the other ingredients: garlic, ginger, cardamom, bay leaves, clove, cinnamon stick and peppercorns, along with coriander, cumin and yogurt.

She advised to keep the whole spices whole and in the dish, and she said that lamb on the bone was better, because the flavor of the marrow infuses the sauce with further richness. Since I came from a family that ate lamb, and had relatives who would dig marrow from bones to eat it, I was not shocked by the concept at all.

I checked that book out of the library over and over and read and re-read it until I had parts of it memorized. Over a period of months, I gathered spices, and hid them in an upper cabinet, and bought basmati rice, and waited for the 4-H lamb season.

That is when all the 4-H lambs, steers and calves were all slaughtered after the county fair, and Kroger’s bought them up, and sold them at amazingly low prices. Every lamb-eating person of Middle Eastern and Indian descent waited for this time in September, and would flock to the meat department and buy cartloads of inexpensive, amazingly tender and flavorful local lamb, and put it in the their freezers. I usually was waiting with them, and would be one leg of lamb, and maybe some stew meat and ground lamb, or for a special dinner, lamb chops.

This year, I was waiting for lamb shoulder meat, and lamb shanks.

And I procured them. While waiting for the butcher to put the meat out, of course, the other customers and I got to talking. It is natural. For one thing, Majid, one of my math instructors from college, was there, and so he and I started up a good conversation about how he had no understanding why most Americans did not like lamb. He was Persian, so the concept of life without lamb was a befuddlement to him. Next to him was a neighbor–an Indian Muslim doctor who had brought her family to Huntington and settled in to practice medicine. This was to be her first time at the 4-H sale, as she had only recently come to West Virginia. She was a lovely woman, expecting her first child, and she asked me why I liked lamb, if most Americans did not.

Well, I explained about how my father’s family were recent German immigrants, and so they brought their food traditions with them, and so she asked if I was going to cook the lamb German-style, and was quite curious as to what that would be like.

I told her that I intended to make rogan josht.

She blinked and then smiled brilliantly. “You know rogan josht? Have you ever had it?”

I had to admit that I had not.

Magid laughed and told her that I was always carrying around cookbooks that I had checked out from the library and taking notes from them, and sometimes had difficulty closing them when class started.

This interested her. “Rogan josht is my favorite dish,” she said.”What made you want to make it?”

I told her about the description, and how it just sounded so good I had to taste it, and since there was nowhere I could get it, I would just have to make it myself.

She nodded sagely, and was going to say something else, but was interrupted by the appearance of the butcher and his assistants, pulling carts out of the back, piled high with wrapped, freshly butchered and cut meats.

I ended up making the rogan josht, some spicy green beans, steamed basmati rice, and lentils with yogurt and mint. I invited our friends, and since I followed Jaffery’s suggestion to leave the whole spices and bay leaves in the sauce, there were skeptical glances when I opened the pot.

A cloud of fragrant steam arose, wreathing our faces. Chris looked in, cocked and eyebrow and said, “It looks like you put a tree in there. I see leaves, twigs and buds.” He grinned and said dryly: “I didn’t know that the Indians stewed Druids.”

He dug in quite fearlessly. Lynne was right behind him, though she elbowed him at the Druid comment. “It smells really good,” she said as she, too, took a healthy portion.

The other Chris and Angie were quieter, but still appreciative. “The spices all smell like different musical notes,” the poetic Chris said. He was always saying things like that, as he worked very hard to be a poet.

Morganna’s father picked through the pot, avoiding the spices, and put small amounts on his plate. I was pretty sure that he wouldn’t like it.

I remember my first taste. An explosion of pepper, chile and cinnamon blossomed in my mouth, tempered by the creamy yogurt and the flowering essence of cardamom and cloves. The meat was juicy and tender, and the ginger, garlic and onions had made a rich sauce that clinged to the meat and flavored the snow-white rice.

“Stewed Druid is good,” Chris commented as he ate. “I don’t even mind the tree bits.”

Morganna’s father didn’t like it, so, until I left him, several years later, I never made the dish again.

But I kept the recipe, smudged with reddish sauce, in a notebook that smelled of my dreams of India.

Over the years, I made it often, after I had come to Athens. It was a special recipe, one that everyone who tasted it loved.. As is the way of things, it changed over time, as I encountered new recipes, new equipment, and tasted different versions at restaurants.

The version I made night before last is the way I made it for my clients. I employed the pressure cooker, because it cut down on the cooking time, so that I could make up to eight long-cooked dishes for them in a fraction of the time it normally would have taken. (I was not paid by the hour, but a fixed rate–therefore, the faster and more efficient I was in cooking–the higher my hourly wage would become.)

Now, the recipe is very different than that one I wrote down many years ago, but it still is very good, and every time I make it and take that first bite, I am transported back to my first experience cooking Indian food, when I was flying blind by the seat of my pants, trusting in Madhur Jaffrey to guide my hands and heart.

Rogan Josht:

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons butter or ghee

2 medium onions, cut in half, peeled and very thinly sliced

1 teaspoon salt

1 1/2 pounds lamb shoulder or leg, most of the fat trimmed: cut it into cubes with or without bones

3 bay leaves (fresh ones, if you can get them, are amazing in this)

8 cloves garlic, peeled and sliced

1 1/2″ cube fresh ginger, peeled and sliced

5 whole cloves

1/2 tablespoon coriander seeds

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon cardamom seeds

1 whole black cardamom

1/2 teaspoon black peppercorns

1/4 teaspoon white peppercorns

1 1/2 teaspoons cayenne pepper

4 teaspoons half-sharp or sweet Hungarian paprika (I used half-sharp)

1/2 quart whole milk yogurt, cream from top stirred in and whisked until smooth

1/2 cup water

salt to taste

garam masala to taste

handful of fresh cilantro or mint, roughly chopped

Method:

In a wide, heavy-bottomed skillet, heat butter or ghee on medium heat. Add onions, and start stirring. When the onions turn transluescent and golden, sprinkle with salt, then keep stirring until onions are deep, reddish brown. Be careful not to let them burn. Scrape them from the pan into a bowl to allow them to cool.

Pat meat dry and put pan back on the fire and let it reheat. Brown meat, in batches if necessary, so as to keep from crowding the pan. Add bay leaves with the meat and allow them to brown slightly–their flavor will permeate the ghee and the meat.

Grind all of the spices, garlic, ginger and the like, with the onions to a thick paste. You know what I am going to say–the Sumeet is the best way to accomplish this.

When the meat is mostly browned, add the spice paste, and keep stirring and frying. Once the meat is browned the spice paste should be very fragrant and starting to stick to the meat and the pan. Use a tiny bit of water to scrape it off the pan.

Bring out the pressure cooker, put the meat, bay leaves and spice paste into it, along with the yogurt and the water.

Bring to a boil, lock down lid, bring to full pressure, then turn down heat and cook for fifteen minutes. When the timer goes off, turn off heat and allow the pressure to fall naturally by waiting until the pressure indicator shows it is safe to unlock the lid. Open the lid, turn the heat back on, bring to a boil and boil away excess moisture, until a thick, clingy sauce is left behind. This usually takes about ten minutes of brisk boiling and evaporation action.

Taste for salt and adjust as necessary. If you like, sprinkle with garam masala, and then garnish with plenty of chopped cilantro or mint.

Serve with raita, steamed basmati or a sweet pillau with golden raisins, saffron and almonds, and a vegetable dish or two. Zak is very fond of Navrattan Korma with this.

As the Paper Palate Turns

Last Sunday, I didn’t do my usual round-up of my posts at the Paper Palate, because I was busy frying spring rolls and steaming buns, so this week, we have a lot to catch up on. It was a pretty heavy news period in the world of food magazines, and luckily, I caught most of the big stories.

First up, three new food magazines have launched or announced that they will launch in the UK and US markets. This is very interesting news, considering that even the giants of Conde Naste, Bon Appetit and Gourmet, lost some ad revenue last year. The UK market doesn’t seem to be as tight, however, and the magazine that just started there, FreeRange, is all about eating locally and getting out of the processed food, supermarket, corporate food rut. I wish FreeRange a great deal of luck, and hope to hear good things about them in the future.

Next, we have the sad news that CHOW magazine, which has had financial woes since its inception two years ago, is once again going to take a six month publication hiatus. I wish them good luck and hope to see them back on the newstands soon.

On to happier topics: US newspapers are finally getting the clue that the Chinese are not the only ones to celebrate the Lunar New Year! A plethora of articles appeared in a flurry last week, relating the New Year traditions of the Koreans, Vietnamese and Chinese who have made their homes in the United States. I rounded up some of the best, and included some recipes.

New York Times restaurant critic Frank Bruni went undercover to walk in the shoes of a waiter in Boston, then wrote about it extensively in the Times. I took this opportunity to expound on my theory that if more people had to wait tables, fewer restaurant guests would treat them like crap.

Just so people who have been reading my magazine reviews in The Paper Palate don’t think that I dislike every food magazine that I see as a matter of principle, here is my review of Eating Well, which is about as glowing as I get.

Finally, with a big heap of thank-yous to reader and friend Shirley Lim, I got the chance to look at a handful of food magazines from Singapore and Malaysia, and give a glimpse of them to the readers of The Paper Palate. I will be doing recipes from these rarities in the coming weeks, so look for new dishes to be coming from yours truly in the near future.

Now, let’s have a taste of what other Paper Palate writers cooked up for us in the past week or so:

Anthony Silverbrow brings us an interesting rumination on the economic and political lessons alcohol can bring us as he gleans goodies from the UK newspapers.

Courtney juxtaposes two stories from the Chicago Tribune on McDonald’s and obesity.

Christina brings us a look at what is in store for readers of the UK magazine Olives.

And here is some of goodies from the rest of the Well Fed staff:

Hand-made marshmallows sweeten the air at Jaay D’s place–and if you follow the recipe, they can make your Valentine sweet on you, too.

Derrick points us to an impropmtu discussion of the perils of prions at eGullet, while commenters at Growers and Grocers come to the conclusion that science reporting in newspapers and magazines tend to confuse rather than enlighten laypersons.

And, Robert brings us a Bloody Mary recipe.

Weekend Cat Blogging: Look, Honey! A Hallmark Card Moment

Don’t you just love it when your cats are so cute that it’s sickening?

Look at these pictures and tell me if your blood sugar doesn’t rise so precipitously that your pancreas threatens to jump ship.

This is how Gummitch and Tatterdemalion were sleeping in my chair when I came into the office. I didn’t pose them that way. No, they did that all on their own. Cute little boogers.

Cats are funny. If I was looking to take a disgustingly adorable picture of them, they would sprawl out in positions that look like they had been run over with a Mack truck or would simply sit and stare vapidly at me. But if I just keep a camera around, and be observant while pretending not to notice, they will strike these impossibly sweet poses for hours.

Or, at least minutes.

For more Weekend Cat Blogging action, check out the antics of Kiri at Claire’s Eatstuff, and find out what all of his kitty friends from around the world are up to.

Greens Are Good

I guess regular readers should know by now that I like greens.

I’ve written about gai lan, choi sum, bok choi, collards, kale and pea shoots. What else can I possibly have to say on the subject?

I mean, we all know that the green leafies are good for us, supplying large amounts of folate, iron, and vitamins A and C. They are also good sources of dietary fiber. They are in season in the cold months of the year.

What is not to love about them?

Well, I guess some people don’t know how to cook them, or they don’t like them cooked southern Applachian style, or they just think they don’t like them because their mammas cooked them weird, but I am here to say you don’t have to cook them to death like we hillbillies do.

You don’t even have to have them as a side dish.

You can turn them into a fabulous vegetarian pasta sauce that is super quick and easy to prepare, is low in calories and tastes really good.

You can make the sauce infinitely malleable, too–by adding or subtracting ingredients until you are satisfied. I added about a half cup of homemade marinara sauce to it because I wanted to, but you don’t have to. You could leave the tomato bits out entirely. You can add any number of the following ingredients, (chile peppers, artichoke hearts, rinsed capers, red bell peppers, zucchini, fresh mushrooms, other greens such as kale, turnip or chard,) and change the character of the sauce as much as you like, or you can leave it as written. You can even add meat to it, in the form of anchovy paste, to really punch up the flavor, or you could add sausage, but that would go against my original intent, which was to make myself a mess of vegetables to eat because I didnt’ want meat.

But, I bet that the sausage would taste good. Bacon probably would, too, but again, that goes against my desire for a mess of greens in my bowl, and so I think you should try it close to the way it is written, first.

Anyway, here it is–a quick, hearty vegetarian dish good for a winter night when you just cannot face meat.

Green Goddess Pasta Sauce

Ingredients:

2-3 tablespoons olive oil

1 medium onion, sliced thinly

4 fat cloves garlic, sliced thinly

dried herbs of your choice–I used thyme, rosemary, basil, oregano and marjoram

1/4 teaspoon salt

black pepper to taste

5 dried shiitake mushrooms, soaked in warm water until soft, squeezed out, stemmed and sliced thinly (keep soaking liquid)

handful dried porcini mushrooms, soaked in warm water until soft, squeezed out and minced (keep soaking liquid)

handful pitted kalamata olives, drained and sliced

1/8 cup red wine

1 pound collard greens, washed and dried, stems removed and cut into 1/2″ wide ribbons

1/2 cup homemade or good quality jarred marinara (I make big batches of it and freeze it for winter)

Method:

Heat oil in a large saute pan. Add onions and cook, stirring, until deep golden. Add garlic and cook until very fragrant, stirring all the while. Add herbs, salt and pepper, mushrooms and olives. Keep stirring and cooking until the olives release some juice. Add about 1/4 cup of mushroom soaking liquid and the wine, and the collards.

Allow wine to boil off and cook collards, stirring until they wilt and turn bright green.

Add sauce, and stir until well combined, and hot.

Serve over al dente pasta with freshly shredded parmesan cheese if you like.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.