A Bowl of Compassion

In my spare time, I volunteer at a local domestic violence shelter. I do something fairly unique in that I go in once a week and cook a meal for the women and kids who are there, so there is something special for them to look forwards to. I take requests and honor them as best as I am able, and clean up after myself and usually, I go into the pantry and organize it so that stuff is easy to find so that the women who cook the rest of the week can see at a glance what materials they have to work with.

What I have found in doing this is that I become a quiet presence in the kitchen.

Women and kids come in out of curiosity at first. Then, they ask if they can help, so we cook together. They sometimes ask me questions about cooking, and I answer. Other times, they get curious as to why I am there and I answer, “Because once I was in a situation where I was abused and some friends helped me get out and go on with life, and so I am repaying that debt.”

Usually at that point, the women open up. And talk.

And I become an ear, a shoulder, a pair of arms. I listen, I comfort and I reinforce. I understand.

It is hard to do. Listening to these stories is difficult, not only because it reminds me of darker times in my past, but because it is hard to be truly open to the pain of another being. However, anything that is truly worth doing is seldom easy; I know that nothing is more healing to a human being than telling her story and having it truly heard. It gives the soul strength to go on. So, I listen.

And I love them. All of them. And it is not always easy, because some of the women there are not kind, gentle “victims” in the sense of the word that we usually think of them. Some of them have abused their kids. Some of them are so caught up in self-hatred and the need to escape that they are alcoholics or addicted to drugs, and they can’t stop even when they are pregnant.

But these “difficult” women deserve compassion and understanding if they are ever going to stop the cycle of abuse and help themselves and their kids grow in a positive way. They have made bad choices, but sometimes, bad choices seem to be the only ones available. And often, they cannot see another way, until someone else reaches out, and touches them with love and shows them another way.

So, that is what I do.

Food is the connecting point, and compassion is the result.

In a sense, I consider what I do a kind of lay ministry to a congregation of the forgotten. Every meal I cook is then a prayer that the sustenance I give might open them to healing from within and without.

This is a soup that is a favorite at the shelter, one that I got requests for several times after the first time I cooked it. If you cook it, I ask that you remember the women and kids who are stuck in bad situations at home, or who are hidden in safe houses and shelters, and send a prayer for their health and safety.

Or, if you have a chance, stop in to your local shelter, and cook up a pot of soup and share it with those who could do with a bowl of love from a friend they never knew they had.

Pasta Fagiole Soup

Serves 10-12

Ingredients:

3 tbsp. olive oil

2 medium yellow onions, diced finely

1 green or red bell pepper, diced finely

6 cloves garlic, minced

3 stalks celery, diced finely 2 bay leaves

½ tsp. chile flakes or to taste

½ cup dry red or white wine (optional)

1 pound Italian sausage, removed from casing and crumbled

½ tbsp.dried basil

dried rosemary, thyme, oregano and marjoram to taste

1 ½ quarts chicken broth

3 14-ounce cans diced tomatoes with juice (seasoned, if you like)

1 30 ounce can dark red kidney beans, drained

1 14 ounce can green limas or cannellini beans or garbanzo beans, drained

3 carrots, peeled and sliced thinly

6 red new potatoes, scrubbed and quartered

¼ pound fresh kale leaves (optional)

4 ounces small dried pasta (small shells, elbows, wheels, rotini, small penne) cooked and drained

Fresh flat leaf parsley or basil, minced (optional)

Method:

Heat olive oil in bottom of soup pot on high heat. Add onion and saute until golden brown. Add bell pepper, garlic and celery, cook another two minutes or so. Add bay leaves and chili flakes and cook another three minutes.

If using wine, add at this time. Boil off alcohol, then crumble Italian sausage into pot. Cook, stirring until sausage is completely browned.

Add dried herbs at this time, and continue to cook, stirring, until very fragrant–—about three minutes.

Add broth, tomatoes, drained beans, carrots, potatoes.

Cook until vegetables are nearly done. (Carrots should still be slightly crunchy.)

Wash kale and remove thick stems. Roll up cigar style, and cut into very thin (1/4 inch) ribbons. Add to soup, and allow to soften.

Add cooked, drained pasta, stir in well. Add freshly minced parsley and/or basil just before serving.

Channa Masala

The ingredients for channa masala, including kala channa–black chickpeas. I usually cook this dish with the more common white chickpeas, but all I had in the cupboard was kala channa yesterday.

Channa masala is one of my favorite Indian dishes. The version I cook is one I learned from a waiter at an Indian restaurant called Akbar, in Columbia Maryland, which is known for excellent cooking. He wouldn’t tell me what was in their channa masala, but we played a game, where I would guess and if I was right, he would tell me if I was right or not. If I was right often enough, he would give me hints. It was how I learned to refine my ability to discern ingredients in Indian foods; he would bring a dish, let me taste it and then ask me what was in it. After weeks of this, I began to be able to pick out the individual spices that would make up the complex bouquet of any given curry.

The channa masala I make, therefore, is based upon Northern Indian cookery principles, since that is the sort of cuisine that was served at Akbar. When we ordered the dish, often our waiter friend would bring us a plate of bhatura to go with it–it is a fried bread that is made to go especially with channa masala (which is also known as channa chaat). There are whole restaurants in Northern India, we were told, which served only bhatura and channa masala. If you ever get a chance to taste them, you can see why–the golden crust of the bread and steaming hot interior is a perfect foil for the tender channa with thier fiery spices.

Most of the time, I make my channa masala with regular white chickpeas, but since what I had was kala channa, or black chickpeas, I used them instead, to great effect. The nutty, somewhat firm texture and character of the kala channa went very well with the flavors of the curry, and since I served them not with bhatura, but on a bed of yellow basmati pillau, they mixed very well with the rice, being smaller and more texturally interesting.

As you can see, they are smaller and much darker than white chickpeas. They stay firmer when cooked and have a delicious nut-like flavor, too.

Channa Masala

Ingredients:

2 cups dried chickpeas, soaked overnight, then drained (or two large cans, drained)

1 pinch asafoetida

vegetable oil

1 large onion, sliced thinly

2” square hunk of ginger, peeled then slivered

1” hunk of ginger, peeled and minced

1 head garlic, peeled and minced

1 jalapeno pepper, sliced thinly

1 tablespoon ground turmeric

1 tablespoon sweet paprika

1 tablespoon cumin seeds, freshly ground

1 ½ tablespoons coriander seeds, freshly ground

½ tablespoon black peppercorns, freshly ground

1 tablespoon amchoor powder (or, several tablespoons lemon or lime juice)

ground cayenne pepper to taste

salt to taste

1 quart vegetable broth

two medium fresh (in season) tomatoes, peeled and quartered (If not in season, use canned tomato wedges)

juice from canned tomatoes or ½ cup tomato juice, if using fresh tomatoes.

chopped cilantro and mint for garnish.

Method:

Cook chickpeas by whatever method you wish to use until they are tender. If cooking dried ones, add a pinch of asafoetida (a resinous Indian spice which has the aroma of garlic and gingerÂ…it is said to help prevent flatulence when cooked with beans). If using canned beans, skip this step. (canned chickpeas are sometimes a bit overly tough. If this is the case, cook them longer after you add them to the spices and water mixture, until tender, adding water as necessary) When I use the pressure cooker, I cook them on high pressure for 18 minutes, then quick-release the pressure, drain them and continue the recipe.

In a large wok, karahi or dutch oven, heat enough vegetable oil to cover bottom. When hot, add onions and cook, stirring until browned and soft.

In cooking Indian food, the step of browning the onions is crucial. Most Americans do not brown their onions sufficiently, which results in an insipid onion flavor. Do not stop at this stage–they are not even halfway done. By the time they are cooked, they should be deep reddish brown, and smell sweet.

Add ginger slivers and minced ginger, and cook several more minutes. Add garlic and cook until golden, stirring continually.

When your onions are a deep golden brown, it is time to add the fresh chile pepper and ginger. I wait until the onions are nearly done–about two shades darker than this–to add the garlic.

Add spices, and cook, stirring one minute, until very fragrant. Add salt and ½ cup of water, stirring well.

The spices go into the pot after the onions are fully browned, and they are mixed in and allowed to cook in the oil for at least two minutes. They become very fragrant and the flavors begin a fruitful marriage.

Add drained cooked beans, the broth, the tomatoes with juice and turn the heat down and simmer to reduce by a third.

Then, I add the liquid, the tomatoes, and the channa, turn the heat down and let it simmer. I like to use vegetable broth, but water will do.

turn to a simmer and cook down into a thickish gravy, about 20 minutes.

Here, you can see how much I reduce the liquid by simmering. It thickens on its own, and takes about an hour or so of good simmering.

Garnish with chopped cilantro and mint.

Here is the finished channa masala, in a bowl over yellow basmati pillau with a garnish of chopped fresh mint and cilantro. The colors are delicious together and the fragrance is redolent of earthy beans, shimmering spices, the tang of ginger and the delicate sweetness of mint.

Eating Feet

No, I haven’t gone and stuck my foot in my mouth.

I’m here to talk about chicken feet.

For all that I adore Chinese food, and have happily snarfed down things that make many Americans shudder to think of, such as tiny whole dried, salted fish, thousand year old eggs, jellyfish and sea cucumber, I had never, until today, partaken of a favorite dim sum dish: chicken feet.

At first it was for obvious reasons–the thought of eating fowl feet squicked me out; I grew up feeding the hens and gathering eggs on my grandparents’ farm–I know what chickens do with their feet. Worse, I grew up helping to dismember said chickens and rendering them fit to eat, and had seen what their feet do when they die, and I couldn’t get the picture of the dying spasms of a chicken out of my head when I saw chicken feet.

But, I hear Chinese folks talk about how good they are, and I have to wonder. What is it about the feet? There isn’t much to them, really, if you think about it. Lots of bones, some skin, a bit of muscle, a lot of tendons and sinew and that is it.

But, the last time we had gone to the dim sum place, the guys at the table next to us had gotten them, and they smelled wonderful. I did not stare, though I was curious as to how one goes about eating chicken feet. It is really impolite to stare at strangers while they eat, even if you are only curious so you can imitate them and not make an ass of yourself trying to eat an utterly unfamiliar food. I suppose I could have tried to explain, but I don’t want to be perceived as a rude gwailo under any circumstances.

So, I kept my eyes forward, and just let the smell of them drive me wild with curiosity. The sounds the two feet eaters were making were maddening–they were obviously enjoying themselves immensely.

So, I decided.

I would ask some of the folks who post over on the forum at eatingchinese.org how exactly, one goes about eating the feet.

And, as I expected, everyone was very kind and generous with their answers.

So today, I took the plunge, ordered the feet, and ate most of an entire order myself while Zak watched in fascination.

They came in a little bowl inside a metal steamer pan, four to an order. As promised, the feet had a pedicure before they came to the table–the claws were clipped off, but they were still recognizable as bird feet. They were bathed in a braising liquid of some sort, and sat, curled up side by side, their skin puffy and wrinkled from long cooking, and stained deep brown from dark soy sauce.

I plunged my chopsticks in, plucked up a foot and took a small bite from one of the toes. My incisors severed the last knuckle and it popped into my mouth, bones and all. I finally realized what the folks at eatingchinese meant when they said not to eat chicken feet at a business meeting or when you go out on a first date. They are not a dish to be eaten quietly and delicately. I ended up slurping, as I sucked the muscle, tendon and skin off the bone, then used my chopsticks to take the bone from between my teeth and convey it to the edge of my plate.

The flavor was evocative, and much richer than I expected. There was the deep sweetness of dark soy sauce, but really the chicken flavor was paramount and it exploded into my mouth. Chicken feet are juicy, and I had to fight to keep from dribbling broth down my chin.

The skin, though softened from being braised, had the flavor of fried chicken, which, as a kid who grew up on Southern country home cooking, I can really get behind. The texture was interesting, both soft and resilient, and I enjoyed nipping the skin off of the bones before popping them in my mouth to suck the tissue off of them. I wasn’t too keen on the tendons; the texture was too rubbery for me, but I ate them anyway.

I discovered that there is a fat pad in the underneath part of the foot, and that is where all the juice and the richness was coming from. Biting into that was like taking a big spoonful of the best, most golden, glorious chicken stock in the world; the intensity of the chicken flavor in that tiny mouthful was as satisfying as an entire bowl of soup. It was utterly delightful.

And that is when I understood why chicken feet are so loved and are seen as comfort food. They are the essence of chicken flavor in a tiny, bony, rather creepy-looking package. I remembered how one of our chefs in culinary school told us that the best chicken stocks included chicken feet, because they were full of flavor and aroma. Everyone recoiled from his comment, except for my Chinese friend from Singapore, who nodded in agreement. “My grandma always puts feet in her soup,” he whispered to me. “It makes it good.”

I ate three of the feet, but had to let the fourth one go. I couldn’t eat another bite; they were too intense, too rich, for me to eat an entire order myself. And no matter what I did, I couldn’t convince Zak to try the last one.

Not even calling them “hobbit hands” did the trick, though he did perk up at the thought.

So, now the question is–will I eat feet again?

Undoubtedly, though I hope I can share them with someone, so I don’t feel beholden to try and eat an entire order myself. I wouldn’t want to fill myself up and miss all the other great dim sum dishes, after all.

The Chinese Cookbook Project III: With an Open Mind and an Open Mouth

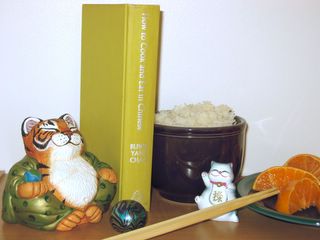

How to Cook and Eat in Chinese by Buwei Yang Chao

One book that is mentioned as being a seminal Chinese cookbook written in English is Buwei Yang Chao’s How to Cook and Eat in Chinese, first published in 1945. This is with good reason; it is often cited as the first attempt to present to an American audience authentic Chinese recipes without resorting to fifteen variations upon chop suey, chow mein and egg fu yung, all Americanized standards popular in the Chinese restaurants of the day, and calling them “Chinese.”

As the book went through at least three editions, two of them revised and updated, and countless printings, I feel safe saying that it was successful at introducing American cooks to many of the core concepts, cooking techniques, ingredients and eating traditions of the Chinese kitchen.

How the book came about it an interesting one; the putative author was neither a writer, nor a lifelong cook, but instead, was a medical doctor. Ms. Chao relates how she did not learn to cook in childhood, but rather, while she was attending medical school at the Tokyo Women’s Medical College. While there, she writes in her author’s note to the first edition, “I found Japanese food so uneatable that I had to cook my own meals. I had always looked down upon food and things, but I hated to look down upon a Japanese dinner under my nose. So, by the time I became a doctor, I also became something of a cook. On my return to China, I surprised my old friends and relatives when I prepared a complete dinner of sixteen dishes the celebrate the opening of my hospital….How did I learn to cook so many things? My answer is: with an open mind and an open mouth. I grew up with the idea that nice ladies should not be in the kitchen, but as I told you, necessity opened my mind first. ” (xx Chao.)*

Dr. Chao, in her own self-deprecating way, sets the tone for her entire work; her main theme, which she reiterates over and over, is that -anyone-, with the application of an open mind, an open mouth, and the will to work hard and refine one’s ability to discern flavors and study, can learn to cook good Chinese food. By using herself as an example, a busy medical student, she assures her readers that they, too, can learn a subject which had previously been presented as very exotic and inscrutable, with mysteries that were too tangled for a mere Westerner to unravel.

Dr. Chao throws all of those ideals of the mysteriousness out of the window and applies her scientifically-oriented mind to the business of unraveling the knotted skein of philosophy, technique and ingredients that weave into the thorny problem of recreating Chinese foods in the setting of an American kitchen. She states that “The Chinese cook or housewife never measures space, time or matter. Hse* just pours in a splash of sauce, sprinkles a pinch of salt, does a moment of stirring and hse tastes the frying-hot juice out of the edge of a ladle, perhaps adds a little amendment, and the dish comes out right. It was only when I started on this cookbook that I began to get some measuring things so I can show you how to do it my way. What my way was, I could not tell myself until I measured myself doing it. ” (31-32, Chao)

Encouraging her readers to be fearless in experimentation, Dr. Chao suggests that most conventions of cooking, serving and eating to be “a little silly,” an understanding to which she came while learning Chinese cookery on her own in Japan. She suggests that it is very well and good and know how cookery is engaged in China, but that nothing replaces “a little thinking.”

“If you cannot get beef,” she writes, “get pork. If you cannot find an egg beater, use your head.” (xx Chao)

The writing style throughout the book is by turns opinionated and droll, with interesting choices in phraseology. One gets a strong feel not only for Dr. Chao’s personality, which is one of sharp wit and quick-thought, but also for the personalities of her husband, Professor Yuen Ren Chao, and their daughter Rulan. It is quite possible, considering Dr. Chao’s lack of skills in speaking or writing English, that not only did her daughter assist in writing the book, as proclaimed in the author’s note to the first edition, but that she and her linguist father, largely wrote the entire manuscript, with Dr. Chao providing the recipes, and technical information on cookery, ingredients and table manners.

Jason Epstein, in an article entitled, “Chinese Characters” written for the June 13, 2004 edition of the New York Times, contends that Professor Chao, whom he describes as whimsical and affable, wrote the text of the book, noting the use of the term, “eatable”, from the Old English root “etan,” instead of the more commonly used, but pretentious “edible, ” from the Latin “edibilis.” As Professor Chao was a celebrated linguist, it is entirely likely that he wrote the manuscript, but to not recognize the collaborative nature of the enterprise does a disservice to all involved. Epstein himself was the editor involved in bringing out the third revised edition from Random House books in 1967, and his description of the two authors is quite evocative, however, his characterization of the author’s note to the original edition as brutally insulting shows a great misunderstanding of how Chinese people tease each other affectionately in the guise of insults.

Having experienced this sort of teasing myself, I found reading the introduction as an intimate look into the family dynamics between Dr. Chao, her husband and daughter, and saw it as being full of passionate discussion, agreement, disagreement, laughter and filial love.

Probably the greatest linguistic addition to the Western lexicon of words pertaining to Chinese food came from the Chao’s book; Buwei Yang Chao is generally credited with the creation of the term, “stir-frying” to describe the action of “ch’ao.” Here Professor Chao’s influence as a linguist is crystal clear; the author(s) write “…the Chinese term, ch’ao, with its aspiration, low-rising tone and all, cannot be accurately translated into English. Roughly speaking, ch’ao may be defined as a big-fire-shallow-fat-continually-stirring-quick-frying of cut up material with wet seasoning. We shall call it ‘stir-fry’ or ‘stir’ for short.” (43 Chao)

I don’t believe I need to belabor the impact of the creation of a unique term in English to describe the specific cooking technique of ch’ao. Before the creation of “stir-fry” as a word meant to convey ch’ao, “fry” or “frying” was used, but the connotation of that word in English was woefully lacking in describing the full action that is ch’ao. Frying in European and American kitchens is a much more sedentary action, even the French term, “saute” is inadequate to describe what happens in stir fry cooking.

Since the word, “stir-fry” entered the English language in 1945, is has become part of common culinary parlance and in fact, is recognized even among people who have never eaten Chinese food in their lives.

It is odd to think that in writing a cookbook, the author(s) changed the English language along the way, for the better.

A great deal of useful, interesting and accurate information is also given on Chinese styles of eating, table manners and the standards of politeness which are in many ways, very different from what many Americans are used to. I was lucky to pick much of this up by watching it in action, but not everyone is observant in the same ways in which I am; the astute discussion of manners listed in the introduction is invaluable. The instruction of how to deal with bones, shrimp shells, chopsticks and wine drinking in the context of a family style Chinese meal or banquet are as applicable today as when they were written and the wry opinions presented still bring a smile and a chuckle to the reader.

The two chapters devoted to ingredients are divided into “eating materials” and “cooking materials.” Eating materials refer to fresh or preserved meats, seafoods, fowl, fish, eggs, vegetables, fruits, tofu, grains and nuts–things that make up the main ingredients for any given dish. Chao discusses how to choose the best eating ingredients and stresses the importance of fresh, clean food to successful Chinese cookery. Cooking materials present the varied condiments that are used to enhance or change the natural flavors of the eating materials in Chinese cookery. It is interesting to see how many of these items, such as fagara, or Sichuan peppercorn, oyster sauce, and fermented bean curd (called soy-bean cheese) are listed as being somewhat available in the US at that time.

Which brings us to the recipes.

There are no recipes for American style Chop Suey or Chow Mein to be found in this book, which is a great departure from cookbooks of the period.

What is found in flipping through the pages are recipes for an array of red-cooked dishes, steamed minced meat dishes, quite possibly the first recipes for dim sum (transliterated as tien hsien) specialties published in English, and vegetable dishes that utilize both Chinese and traditional American vegetables. There are a few recipes that are quite clearly adaptations of American ingredients into a Chinese culinary context–Salted Turkey is an adaptation of a traditional duck recipe to utilize the more commonly available turkey, and the Chinese Style Roast Chicken (there is a variant on Turkey as well) show a typical American cooking method fused with Chinese seasoning.

The recipes look delicious and many are similar to recipes I learned by watching Huy and the other chefs cook, especially when they were cooking for employee dinners. None of them look as if they were attempts to cater to American tastes–there are recipes for tripe, chicken gizzards and pig’s feet, though I would note that when this book was published, more Americans were apt to eat such “variety meats” as they were called at the time for a number of reasons. One, American households were not as generally affluent as they are now, and many lower-income people commonly ate lesser cuts of meat, including organ meats. This is not so true in these days of processed and convenience foods. And two, there was a war on, and meat rationing was in force, and variety meats were more available and less expensive than prime cuts. In fact, one of the selling points of the book was that it showed how to stretch smaller amounts of meat by cooking it with vegetables in such a flavorful way that no one would notice the lack.

Unlike the Watanna/Bosse book, I can see myself cooking from How to Cook and Eat in Chinese. In fact, I think that after we move and I become settled into my new kitchen, I will set forth to cook recipes from each of these out of print cookbooks, in order to evaluate the results. I think it would be a worthy project to engage in and record.

As I close the book and look at its plain yellow cloth cover, I cannot help but think that it is a shame that this little gem is out of print and thus is relatively unavailable to the student of Chinese cookery. The information presented therein, even though it was written more than fifty years ago, is still fresh, interesting, useful and relevant in today’s world. I only hope that by writing about it here, I can help rekindle interest in the book, and perhaps get it out to a wider audience while copies of it are still available in the used book market.

I know that there are plenty of people with open minds and mouths who would enjoy devouring the feast of cultural information, culinary experience, and linguistic expertise that are wrapped together with a liberal dose of sparkling humor in the pages of this book.

* The page designation xx is the actual Roman numeral used for the notes in the front of the book before the actual text of the book starts.

*“Hse” is the gender-neutral term for he/she coined by Professor Yuen Ren Chao, Dr. Chao’s husband, to make up for a third-person singular pronoun in English other than the rather formal and stiff sounding, “one.” As I will write later, it is quite possible that Professor Chao wrote more than a little of the manuscript of Dr. Chao’s book, since she admits in her forward that she “speak(s) little English and writes less.” (xx Chao)

One Potato, Two Potato, Red Potato, Blue Potato

The potato section at the North Market Produce stall. The blue potatoes share space with Yukon Golds, red potatoes, the usual russets, fingerlings and ping-pong ball sized new potatoes.

I love potatoes.

Which is evident by my general size and shape. I am not small. Potatoes will do that to a person. Give you substance.

They are the perfect peasant food, and I grew up eating like a perfect peasant. Meat, potatoes and vegetables. Three food groups on the plate. Sometimes, we had bread, too, but there were always potatoes, even if we had biscuits, cornbread or dinner rolls, potatoes were ubiquitous.

The best potatoes were the ones Grandma and Grandpa grew. His favorite variety was the Kennebec, but I also remember him growing the Irish Cobbler, too. But he would hold forth at the dinner table about the good qualities of the Kennebec, while the rest of us shoveled many ounces of said potatoes into our gullets.

My Gram, Dad’s mother, on the other hand, preferred red potatoes. Hence, her mashed potatoes had a different texture than Grandma’s who always used russet-type potatoes, which have a drier, mealy texture that sheds moisture. I learned early on that the texture of Gram’s mashed potatoes was silkier and more moist, in part because she used real butter and half and half in hers, but also because the red potatoes are a waxy potato with a starch structure that holds onto moisture.

Also, Gram used a hand potato masher, vintage from the 1920’s–a steel disk with stars cut out on it with a steel stem growing up from it perpendicularly, with a green–painted wooden handle that fit perfectly into her palm. She was very thorough in her mashing and beating, but there were always small lumps that escaped her ministrations, and Gram always said that was how you could tell they were real.

Grandma’s potatoes tended to be lighter and fluffier, and were always perfectly smooth. She whipped hers up using her old Sunbeam stand mixer, and she served them on the table right from the heavy glass mixing bowl that went with the mixer. She used milk, sometimes evaporated milk, and margarine in hers, and the flavor of the home grown potatoes really shone through the minimal enhancements.

I wonder what my Grandpa would have thought of blue potatoes?

He didn’t much care for the red ones; he didn’t like the waxy texture or the sweeter flavor. I suspect that not only would the unusual color of blue potatoes put him off, but the slightly sweet flavor would distress him, too. He always said that potatoes should taste like the earth they grew in, and that when we ate them, we were eating the land itself.

I reckon he might say that there must be something wrong with the land if the potatoes are purple.

For, indeed, blue potatoes are really purple, once you cut into them.

The vivid violet color of the raw potato fades to a medium blue when cooked. More color is retained if you cook the potato whole, as the pigments which make the potatoes such a rich royal purple, anthocyanins, are water soluble. They tend to be concentrated in the cell vacuoles, so if you cut the potatoes and damage the vacuoles, the color leeches out.

In addition, the vacuoles which store anthocyanins tend to be acidic, and most tap water used for cooking is slightly alkaline; in an acidic environment, the anthocyanins tend towards the red area of the spectrum, while in an alkaline environment, they tend more towards the blue-green coloration. So, if you cut up your blue potatoes and cook them in regular tap water without adding any acid, not only do you lose a significant amount of pigmentation to the water itself, you also change the color by virtue of a loss of acidic environment.

When cooking purple vegetables like say, red cabbage, it is traditional to add an acidic ingredient like vinegar (sweet and sour cabbage, anyone?) in order to keep the cabbage reddish purple, rather than have it turn a kind of greyish blue, which is not an appetizing color. I suppose you could do the same with blue potatoes, but I have found that simply boiling them whole helps retain a lot of the color, though it does fade to a more pale violet color rather than the bold royal violet hue of the raw vegetable.

If you are wondering why I know so much about plant pigments and the chemistry of cooking, you can thank Harold McGee, author of On Food and Cooking and The Curious Cook. He is one of my favorite authors; a chemist by profession, he has unraveled the mysteries of cooking and baking and has written the best tome to explain the science of the kitchen to lay persons I have ever read. And believe me, I have read all of the popular books on the subject, and his is the most complete and sensible of the lot.

Besides, he is fun to read, and his works have singlehandedly made me a much better cook than I would ever have been without reading them. His books should have been required reading in culinary school; I found my knowledge of his work invaluable when navigating the perilous shoals of baking and pastry classes. It also helped when it came to vegetable cookery; my vegetables were consistently prettier than other students, and I have McGee to thank for it.

Which brings me to the question of what exactly does one do with blue potatoes? Well, I like to make violet color mashed potatoes with them, but they are a bit shocking on the plate. Especially so for guests who are not used to my fits of culinary whimsy where I cook up a bunch of weirdly colored things and present them together. Some folks use them in potato salad, and I think that so long as you didn’t use a mustard-based dressing, that would be great; a German potato salad made with them and some Yukon Gold potatoes would be striking.

My very favorite use for them is in Indian cookery, most specifically in a dish of potatoes cooked with spinach, called Saag Aloo. In many restaurants, saag aloo is a very creamy dish, with pureed, somewhat overcooked spinach in a somewhat spicy dairy-based sauce, with chunks of boiled white potato dotted throughout.

I make mine differently. I generally start with carefully browned thin slices of onion and garlic cooked until golden. Then, I add ground spices, and cook until they are fragrant, then add the spinach, which I have thawed and squeezed the excess water from. I turn up the heat and add a bit of yogurt and a tiny bit of cream, just to bind it together. Potatoes which I have cooked separately whole, are drained, cut up into dice and added, and the entire dish is cooked down until the still vibrant green spinach clings to the potato chunks, and the spices are married together into a melange of subtle flavors. Sometimes, chopped fresh mint is added at the last minute as a garnish, and I usually use it as a dish alongside something a bit spicier like a vindaloo or a korma.

I find that using a combination of red-skinned white potatoes and purple potatoes really makes the dish turn out beautifully, and makes it seem as if it tastes even better. The jewel-like colors are at home on a plate of Indian food; it makes me think of the gorgeous silk saris and the polychromatic painted statues of Hindu deities bedecked with flowers that are venerated with food offerings in the great temples and houses of the faithful. The dish is like a green field dotted with white and purple wildflowers, and that visual ideal only helps boost the mingled flavors of the vegetables and spices.

Blue potatoes add color interest to a dish of Saag Aloo.

Saag Aloo

Ingredients:

2 medium sized red skinned potatoes and 2 medium purple potatoes, scrubbed well and cooked in salted boiling water until tender

1 medium onion, cut in half and sliced thinly

1 tbsp. ghee

2 tbsp. vegetable oil

3 cloves garlic, minced

1/4 tsp. cardamom seeds, freshly ground

1 tsp. fennel seeds, freshly ground

1/4 tsp. fenugreek seeds, freshly ground

1/4 tsp. black peppercorns, freshly ground

1/4 tsp. ground cinnamon

1/2 tsp. coriander seed, freshly ground

1 8 ounce package frozen chopped spinach, thawed, drained and squeezed dry

1/2 cup whole milk yogurt

1/4-1/2 cup cream

salt to taste

1/4 cup fresh mint leaves coarsely chopped (optional)

Method:

After the potatoes are finished cooking, drain and cut into a medium dice, and set aside.

Heat ghee and vegetable oil in a heavy skillet. Add onions and cook, stirring constantly, until they are medium brown. Add garlic and cook, stirring constantly until garlic is golden in color and very fragrant. Add spices and cook one minute more, until the air is strongly scented.

Add spinach, along with yogurt and the smaller amount of cream. Add potatoes, and salt to taste and cook, stirring, to reduce sauce until the liquid is almost gone and the very green spinach clings to the potatoes.

If you wish, you may add a bit more cream to make the dish a bit more moist; I prefer it nearly dry.

Salt carefully; you can easily over salt if you salt it to perfect taste while there is still a lot of liquid. Under-salt at first and then reduce the liquid by simmering it off, then taste again and correct the salt at that time.

You can cook this ahead of time and set on a cold burner if you need to, then reheat gently with another bit of cream or some milk, until it is sufficiently hot. This has the effect of deepening the flavors, and so long as you take care not to overcook the spinach, nothing is harmed, and in fact, the dish is improved in this way.

Add the mint just before serving.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.