The Chinese Cookbook Project II: This Little Book

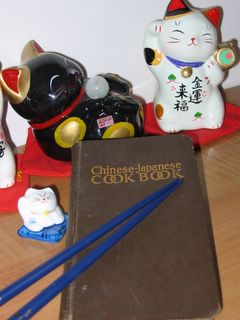

Surrounded by maneki neko, and shown with a pair of chopsticks in order to give a sense of scale, is Sara Bosse and Onoto Watanna’s Chinese-Japanese Cookbook.

Earlier in this blog, I wrote about how I acquired a copy of Chinese-Japanese Cookbook by Sara Bosse and Onoto Watanna, published by Rand McNally in 1914. What I did not talk about was the book itself, its provenance, and its authors. It turns out that while this may not be the very first Chinese cookbook printed in English, it yet is a fascinating piece of Asian-American history, the depth of which can only be guessed by looking at its rather unassuming exterior.

Reading the text itself is interesting; while there are many recipes that will sound familiar to students of Chinese cuisine, the way in which cookery itself is approached is very different than what we are accustomed to reading in cookbooks today. For one thing, the standard recipe format which includes a separate list of ingredients is present, but instead of putting the list in a column, it is written in paragraph style; this is fairly typical for cookbooks of this time period. More interestingly, the reader is advised on page 9 under the “Rules for Cooking,” that in order to make a rich stock for soup, “use only a quart of water for every pound of veal, mutton or beef bones.”

Especially considering that the recipes recorded in this book are supposedly handed down from Vo Ling, who was the principal cook to “Gow Gai, one time highest mandarin in Shanghai, (page5)” the passage regarding the use of veal, mutton and beef bones struck me as incredibly odd. As I have come to understand it, most Chinese stock recipes for soup rely almost exclusively upon chicken carcasses and pig bones.

Beef was seldom used in China for eating as oxen were necessary as beasts of burden. I have not run across any recipes for veal that I can recall, and my study has led me to believe that mutton and lamb are meats seldom eaten among the Chinese, except in the northern regions where the Mongolian influence is strong, and among Chinese Muslims. My personal experience has also born these findings out; with few exceptions, most of the non-American born Chinese people I have known have shown little liking for either lamb or mutton. One friend in culinary school who was from Singapore even wrinkled his nose and shook his head when offered a bite of rare lamb chop, declaring it to be “stinky meat.”

Other oddities that stood out as I read along was the recipe for fried bean sprouts (page 57) that directs the reader to fry one pound of bean sprouts in one quarter pound of fresh pork fat uncovered for five minutes, and then to add three tablespoons of soy sauce (which is called syou, apparently from the Japanese term, shoyu), and salt and pepper. So far, other than the large amount of pork fat, this sounds like a pretty standard and tasty bean sprout stir fry, however, after the addition of soy sauce, salt and pepper, the cook is told to cover tightly and allow it to simmer for fifteen minutes.

After fifteen minutes of simmering, the likelihood is that the bean sprouts are going to be on the slimy and mushy side, such that I cannot imagine any of my Chinese friends and aquaintances wanting to eat them. After directing the reader on how to grow ones own beans sprouts so as to avoid the canned lesser product, why then cook them until they have the same texture as the ones from a can?

Interestingly, recipes are presented for chow mein that include deep fried noodles, and chop suey; both dishes are Chinese-American adaptations or inventions, created to use available ingredients or appeal to American tastes. These recipes are recognizable even today, ninety-one years later, as dishes that you could walk into many American Chinese restaurants and order.

According to the preface of the book, by 1914, Chinese restaurants had spread out from the Chinatowns in large cities and had become competitive with even fine dining establishments. The book appears to have been written with the American housewife in mind; and instructions are given to help her recreate dishes she may or may not have tasted in a restaurant.

Fresh and canned bean sprouts are mentioned in the text, as is soy sauce and fresh water chestnuts. A recipe for bird’s nest soup is presented, which tells us that dried bird’s nest was also available, at least in Chinatown shops; these mentions give us a glimpse of what Chinese ingredients had begun to be imported into the American marketplace at the turn of the century.

The cooking fats mentioned most often are pork fat, lard, suet, chicken fat, and strangely enough, olive oil. The use of animal fat is not surprising; many older Chinese cookbooks and cooks I have spoken with have shown preference for the use of rendered animal fat in cookery, both for reasons of flavor and frugality. I suspect that the presence of olive oil reflects an adaptation to the most readily available vegetable cooking oil in the American markets at the time.

Just as interesting as the text of the book is the identity and history of its authors, neither of whom was Japanese, nor had ever been to Japan. Onoto Watanna was the pseudonym of Winnifred Eaton, and Sara (Eaton) Bosse was her sister. The two of them were the daughters of an Englishman, Edward Eaton and a Chinese woman, Grace “Lotus Blossom” Trefusis. Their father had been a silk merchant, and had met their mother, who had been adopted by English missionaries and educated in England, while he was visiting her home city of Shanghai.

The two had wed and gone to live in England for a time, then moved to Montreal, Canada, where Winnifred was born. Winnifred was a talented writer and at the age of fourteen, had articles published in a Montreal newspaper. She began selling stories to magazines in both Canada and the United States. At the age of seventeen, she moved to Jamaica to work as a stenographer for a Canadian newspaper. A year later, she moved to Chicago and began publishing short stories under the Japanese pseudonym, “Onoto Watanna.”

In 1899, she published her first novel, Mrs. Nume of Japan and two years later, after she moved to New York City, she published her second novel, which became a runaway success, A Japanese Nightingale. She is often credited as the first Asian-American novelist published in the United States.

Onoto Watanna ceased to be a nom de plume, and became a persona as Winnifred posed for publicity photographs dressed in kimono, and passed herself off as a Japanese noblewoman. She would not acknowledge her Chinese heritage because of the very strong racist attitudes and laws against Chinese immigrants in the United States at that time. American attitudes towards the Japanese were much more favorable (probably because of the Meiji government’s partnership with the American government and corporate interests in efforts to modernize Japan), and there was a great deal of interest in the “exotic” nature of Japanese society.

A topic that seemed central to many of Eaton’s works was that of romance between Anglo-American men and Japanese women. Considering her background, this is not surprising, however, it is interesting to note that she both plays into and subverts racial stereotypes about Asians in her works. (An older sister, Edith Maude Eaton, was also an author; she confronted racism against the Asians more directly by writing very gritty stories revolving around the plight of Chinese immigrants in North America under the Chinese pseudonym of Siu Sin Far.)

Sara Eaton Bosse did not seem to be a writer; no other works are attributed to her. According to Winnifred Eaton’s biographer and granddaughter, Diane Birchall, it is likely that Sara was attributed as a co-author in order to justify the addition of Chinese recipes. Of course, being Japanese, there would be no logical reason for Onoto Watanna to know how to cook Chinese food. Birchall also notes that while the sisters claim that the Chinese recipes were passed down from Vo Ling, she believes that it is likely that the cook was as fictitious a personage as Onoto Watanna. She further states that Winnifred Eaton was a terrible cook and boiled everything to death.

These facts could very likely account for the mushy bean sprout recipe and the out-of-place instruction to use veal, mutton and beef bones to make stock for Chinese soups. It is also possible that their mother, in cooking for their father, used such ingredients in order to create dishes that satisfied both to her husband’s English palate and her Chinese aesthetic sensibilities.

I am still doing research on this little book; considering it is a slender volume only one hundred and twenty pages long, there are plenty of interesting details and tidbits that hint at the history of Chinese cooking in North America. Even more fascinating are the details of Asian-American life at the turn of the century and the complex issues of race, gender and stereotypes that the works of the Eaton sisters record and explicate.

Stay posted; as I do more research, and actually read the fiction of Winnifred and Edith Eaton, I will likely record my thoughts here.

Book Review: Land of Plenty

Land of Plenty

Fuchsia Dunlop

2001

Fuchsia Dunlop is an amazing woman.

For one thing, she is the only non-Chinese female graduate of the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine in Chengdu, China. For another thing, she managed to write down the recipes for most of the dishes that Huy used to make at The China Garden for employee meals which I had been pining after for more than a decade. Her accurate rendering of these traditional recipes has put into place a few missing puzzle pieces in my quest to recreate the dishes that have haunted my memory.

In addition, she has managed to convey in a 394 page book a vivid picture of life in Sichuan province, with loving descriptions of teahouses, street hawkers and banquets. Her experiences at the culinary institute echoed my memories of culinary college here in the states, however, she had the added excitement of learning a cuisine that was totally unfamiliar to her own cultural background in a completely different language.

With in her book, Dunlop codifies the twenty-three distinct flavors of Sichuan food, lists the necessary pantry items, explains the different cooking techniques–some of them unique to Sichuan province–and provides a glossary of Chinese characters with anglicized spelling and meanings in English. The book is sparsely illustrated with gorgeously composed photographs which show ingredients and finished dishes in full color.

Cooking from this book is an absolute pleasure. Over time, I have adapted all of the recipes I have tried to reflect my memories of the home style dishes that Huy made as well as my own tastes, but I always make the recipe as written first. While I like my adaptations better because they are mine, her recipes are authentic and absolutely, hands-down, the best Sichuan recipes from a book I have ever used.

I understand that she is now working on a book about the cuisine of Hunan province, which is equally under-represented when it comes to cookbooks in English.

I cannot wait to read it.

More importantly, I cannot wait to cook from it.

The ingredients for Sichuan Red-Cooked Beef with Turnips; note the Chinese turnips half-hidden beside and behind the soy sauce.

Red Cooked Beef with Turnips

The first time I had this dish was as an employee meal one blustery winter night at Huy’s restaurant. It was served in a bowl with a huge handful of cilantro leaves scattered over it. We ladled it over our bowls of rice and ate with chopsticks and a spoon. I took a bit of it home to Zak and he raved about it, and so I made it my mission to figure out how it was cooked. For years, I tried every kind of Red-cooked beef recipe out there, but never got the right taste until I learned from reading Fuchsia Dunlop’s book that in Sichuan, the ingredient that makes red-cooked beef red is not soy sauce as it is in the rest of China, but Sichuan chile bean paste. I had been using chili garlic paste in order to give the dish its characteristic deep heat, but the flavor was never, ever right. The first time I made this dish with that ingredient, Zak came running downstairs and said, “That’s it!†You can use daikon radish, Chinese turnips or regular American turnips in this dish. Just make sure to add them at the end so they don’t disintegrate. I like Chinese turnips the best of the three, though Huy made it with daikon. While it is not traditional, I have added taro roots and sweet potatoes to this stew and they are both very good in it.

This is my adaptation from Land of Plenty; I added some more scallions, ginger and garlic to it., and I prefer the use of chuck roast to short ribs.

Ingredients:

2-3 pounds good quality chuck roast

2-3 inch piece of fresh ginger, unpeeled

4 scallions, white and green parts, trimmed

3 cloves garlic, peeled

3 tbsp. vegetable oil

6 tbsp. or to taste of Sichuan chili bean paste (do not substitute chili garlic paste)

1 quart beef broth (I prefer the kind in the aseptic package)

4 tbsp. Shao Hsing wine or dry sherry

2 tsp. dark soy sauce

1 tsp. whole Sichuan peppercorns, toasted

1 whole star anise

1 black cardamom pod*

1 ½ pounds turnips, Chinese turnips or daikon radish

Fresh cilantro to garnish (to taste, but like Huy, I like lots of it)

Method:

Cut the chuck roast into several large pieces. Slice the ginger thickly, then smash slices with the side of the knife. Cut the scallions into two or three pieces each. Smash the garlic cloves.

Heat the oil in a heavy dutch oven or soup pot, and add chili bean paste and fry until fragrant–about thirty seconds. Add the ginger, scallions and garlic and fry another thirty seconds. Add in beef, broth, wine, soy sauce and spices. Bring to a boil. If any scum rises, skim it off.

Turn down the heat and simmer until the beef is fork tender–about two to three hours.

When the beef is tender, trim and peel the turnips. Cut them into thick bite-sized chunks. Add to the beef, and cook until the vegetables are just tender.

If you wish, you may thicken the sauce with a cornstarch and cold water slurry.

Garnish with lots of cilantro leaves.

*Black Cardamom is available at Indian grocery stores under that name. In Chinese markets, it is found under the name cao guo or tsao kuo. It is about the size of a Niscoise olive, and has a shaggy brown outer pod that looks rather like the outside of a coconut. It has a smoky, dark flavor that is really, really good with beef. I use it more often in Indian cookery than Chinese, but I have found that with this dish, I really like it, and find it to be essential.

The finished dish, garnished with cilantro.

Greener on the Other Side

A selection of Chinese greens: baby bok choy, Chinese broccoli or gai lan, and in the back, snow pea shoots. The sausages in the green dish are lop cheong.

In ruminating on the Appalachian tradition of cooking greens with pork, I was reminded of how I got Zak to eat greens. It did involve cooking dark leaves with piggy bits, but not in the traditional Appalachian country style I had grown up with. It came about by riffing on the Chinese way of cooking and eating greens.

The Chinese love greens as much, perhaps more, than hillbillies do. I discovered this years and years ago when I was working as a waitress at The China Garden restaurant in Huntington, West Virginia.

It was the end of lunch shift, and everyone was pausing in our preparations for the dinner shift to have some lunch. There were three of us waitresses working: Heather, a tough-talking but good-natured native West Virginian who had grown up in Columbus, Ohio, June, a young Chinese immigrant who had been a nurse and was working as a waitress to put herself through nursing school in the States, and myself. We had dished up some of whichever lunch special appealed to us and sat down at a table together to eat. Heather and I bantered together, while June, who was very sweet-tempered, laughed at our risqué jokes.

Mei, the chef-owner’s wife, came out of the kitchen with a small platter, and came to our table. We smelled something dark and delicious, and Heather and I, ever the adventurous eaters, looked up eagerly. “Whatcha got, Mei?†Heather asked, leaning forward to get a better look.

Mei waved her hand, as Huy and the rest of the kitchen staff came out and sat at the back table, carrying platters and bowls of rice. Huy was watching us as he sat down and began tucking into his bowl of rice.

Still waving her hand and shaking her head, Mei said, “Oh, its nothing, really, nothing fancy or special. And you probably won’t like it anyway, but Huy wants you to try it.â€

I watched as she set it down and deeply inhaled the perfume of toasted sesame oil. It was some kind of greens, cooked until barely wilted and bathed in a shining sauce. To call them verdant was an understatement–they were colored in nearly obscene shades of brilliant green. My nose twitched. They smelled really good.

Heather was looking at them, too. She licked her lower lip, and raised a dark eyebrow at Mei. “What is it?â€

Mei shook her head, “Oh, just some greens, Chinese greens, but I don’t think you will like them. I told Huy that only Chinese people like them. Americans won’t like them, but he wants you to try them.â€

I shifted in my chair to look past Heather’s shoulder, and saw not only Huy, but Lo and the rest of the kitchen staff watching us intently. I shrugged my shoulder and picked up my chopsticks.

Heather had beaten me to the first bite. “Oh, Mei you know how Barb and I are. We’ll try anything once, right?†She plucked up a choice stalk with her chopsticks and popped it in her mouth, and chewed slowly. Mei, June and I watched her. She swallowed, nodded her head and said. “Mmmm. Tastes like grass.†A satisfied smile quirked the corner of her mouth.

Of course, I snagged a bit of stalk with darker, wilted leaves attached and bit into it. It was bitter and sweet and crunchy and soft and salty and redolent of the smoky wok and the dark mystery of sesame oil. I closed my eyes and nodded. Greens. I swallowed and smiled up at Mei. “Mustard greens. Oh, man, these are good.â€

Mei blinked, and stared. “Yes, mustard greens, that’s what they are!â€

June had been watching all of this with interest. She took up a very small bit of it and put it in her mouth, biting down on the crisp stalk. Instantly her face puckered and she shuddered, shaking her head. “Ooooh,†she exclaimed, her voice tinged with disbelief. “Tastes like grass.†With that, she shook her head and pushed the platter away from herself and toward Heather and I.

The back table erupted with laughter. Mei feigned great shock and pointed at June. “Wha–you never eat mustard greens?â€

Heather took up another bite and chuckled. “So much for only Chinese people liking these.†She winked at me, and we both began eating the greens in earnest. Pausing to grin over at June, Heather added, “That’s okay. It means more for us.”

June blushed and shook her head, laughing. “No, I don’t like grassy things,†she said to Mei.

Mei watched us eat for a few seconds then tapped me on the shoulder. “Where’d you learn to like mustard greens, huh?â€

I looked up at her and winked. “Didn’t you know that hillbillies and rednecks eat greens, too?†I looked down at the platter and added,†Though we don’t cook them so fancy or pretty as that.â€

She shook her head. “I had no idea,†she answered, heading over to her table where lunch waited. As she sat down, Huy said, “I told you they’d like.†He peered over at June and made a face, teasing her. “Except June. She’s too spoiled.â€

June switched into Mandarin to answer Huy back and the banter between the two tables flowed around Heather and I, a river of words and laughter we could not parse.

But we didn’t care. We had greens, and we ate the entire platter contentedly.

Years later, I decided that it was high time that Zak learn to like greens.

I decided to use his love of Chinese food to my advantage, and bought several varieties of green leafies, and began cooking them in a hot wok with sliced garlic, dressing them simply with a bit of sugar, some wine and light soy sauce, and a dash of rice vinegar. When they were done, I would drizzle sesame oil over them and scrape them out of the wok onto a waiting heated platter.

He ate them up.

My greatest coup was getting him to eat kale. I happen to love lacinato kale–a variety that has fairly tender, wrinkled ovoid leaves with crisp but not tough center veins. I had some lop cheong–dry cured Chinese pork sausage that has a good bit of sugar in them, so I diced it very small, and minced up a clove of garlic with an equal amount of fresh ginger. I cut the kale crosswise into thin ribbons so each slice had a bit of the crisp center rib.

I heated up my Cantonese style cast iron wok which I had recently bought from The Wok Shop in San Francisco, and tossed in the minced aromatics and the diced sausage. I cooked them until the sausage had started to brown and the garlic was golden, then added a drizzle of homemade chile oil with seeds and added the kale. I stirred like mad, letting the kale quickly wilt, and shook a bit of thin soy sauce into the wok along with some chicken broth. A sprinkle of sugar and a dash of chianking black rice vinegar finished the greens, and onto the platter they went.

They were by turns sweet, sour, smoky, gingery and garlicky. The sausage had rendered their fat so everything was coated with a porcine richness that exploded on the taste buds every time you bit into a piece of it. It was an unqualified success.

At a subsequent visit to the Columbus Asian Market, I picked up more lop cheong, and was replenishing my supply of greens. A little Chinese grandmother glanced into my cart and asked what I was going to do with the sausages. I told her about cooking them with greens.

She thought it sounded like a good recipe and said she might try it herself. In the meantime, she pointed out the pea sprouts and asked if I knew what they were, and we were launched on a bilingual discussion of greens, how to buy them, how to cook them and what ailments they were good for curing.

Which was fine, except we were slowing down the traffic in the produce section.

Time and again, in my multi-ethnic explorations of food, I have found that the culinary arts can become a bridge that brings people from very different backgrounds together. Food is a language that transcends linguistic and cultural boundaries, and when two native speakers of the culinary mother tongue come together, impassioned communication results. We can see that while we may have grown up on opposite sides of the planet, we have something in common which we both love.

A simple plate of greens.

Yin and Yang

Teaching culinary arts is one of my passions. I watch people learn; I have spent a large amount of my life studying and gaining experience and I enjoy sharing the information I have gained with others along the way. I like the shine of discovery in the eyes of students who are just now embarking on the journey that I first started so many years ago, and I love seeing others who are just as excited about food and cooking as I am have new experiences for the very first time.

Last night I taught an Introduction to Sichuan Cooking class at Sur la Table; it was a hands-on class and it was filled with seventeen people, which is the limit to the number of students we teach hands-on in that venue. I taught three traditional Sichuan dishes: dry fried green beans with minced pork, Ma Po Tofu, and red-cooked beef with turnips. I also taught an original recipe, called “Too Hot Chicken†a stir fry that is based upon Sichuan flavors. The four recipes were meant to be put together into a dinner party, with the first three recipes and steamed rice being able to be made ahead, with the only dish that required last minute cooking being the stir-fry. One of the mistakes a that a lot of novice cooks make when learning Chinese food is they assume that everything is stir-fried and so when they give a dinner party, they wear themselves out stir frying everything at the last minute. In fact, Chinese home cooks would never construct a party menu in that way, but would utilize other cooking methods: steaming or braising, for example, which produce dishes that can be cooked ahead of time and then reheated when needed, or which cook undisturbed on the back of the stove without any supervision from the cook other than starting a timer.

I like to give a great deal of cultural information while I am teaching, often in the form of stories or examples from my own learning experiences, and I always tell my students that they can ask me questions at any time. One question that came up last night from a very enthusiastic and attentive student was, “What is the difference between Sichuan and Cantonese cooking?â€

I thought it was a very good question, and one that deserved a well-thought out answer.

One of the great fallacies that many Americans hold in regards to Chinese cookery is that there is one over-arching cuisine that is known as Chinese. That simply is not true; China is a vast country, with many different regions that have distinctive climates, growing seasons, crops, languages, cultures and correspondingly different culinary traditions. Some authors say that there are four main schools of Chinese cookery, others identify up to eight distinctive named variants in cuisine.

Americans come to this notion in several ways. One is that most Americans are woefully under informed when it comes to anything about China; most of us know very little about the history, philosophy or culture of China, because for many years, that country was extremely isolationist, and so there was little opportunity to learn anything accurate about it. Opportunities to share and learn have broadened within my lifetime, and cultural exchange that is available to the general public has exploded in the form of martial arts studios, Chinese medical practitioners, Buddhist teachers and temples, films, books, musicians and theatre companies.

The greatest influence upon American ideas of Chinese culinary homogeneity has come not only from a lack of cultural awareness in general, but from American experiences at Chinese restaurants where the same handful of Americanized Chinese foods are presented with slight variations from city to city, across our nation. Most Americans think of chow mein, chop suey, sweet and sour pork with the scary day-glo pink sauce and egg rolls as “Chinese food.â€

This misconception is changing as Chinese restaurants develop and change in the United States, but the process is slow. The dishes mentioned above are still available on a majority of Chinese restaurant menus and many Americans order and enjoy them. What they do not know is that while those dishes are based upon actual Cantonese recipes, they have been strongly adapted to American tastes, and so are in essence more strictly understood as “American-Chinese†food, or as I call it, “American-Chinese Restaurant†food.

Which brings us back to the question of what are the differences between Sichuan and Cantonese foods?

Sichuan food tends to be robustly cooked and intensely flavored with a variety of condiments, from spices, pickled vegetables, chilis and vinegars, which are used in combination to create twenty-three distinct, named flavors, such as fish-fragrant flavor, strange flavor and scorched chili flavor. A great variety of cooking styles are employed in manipulating flavor and texture in Sichuan food, including cooking methods unique to the region such as dry-frying, which is a process that involves slow cooking in a wok over high heat with little oil in order to dry out and change the texture of the ingredient being cooked in this way. Chile peppers are used in a variety of ways–dried whole with seeds and toasted, ground up and steeped in oil, fresh and sliced or in a uniquely Sichuan condiment, fermented chile bean paste. In addition, the berries of the prickly-ash tree, which have a fragrant flavor and produce a pleasant tingling numbness on the tongue and lips, are used in many different ways. These Sichuan peppercorns, as they are called, create a distinctive flavor which is not often used in any other regional cuisine in China.

By contrast, the style of Cantonese cookery is one of restraint and sublime simplicity. The cooking of Canton is the regional style most highly regarded by Chinese gastronomes, in part because of the great respect paid to the quality and freshness of the ingredients used in creating a dish. Pure, fresh meat, seafood and vegetables are skillfully cooked and adorned with a minimum of condiments in order to bring out the natural fragrance, color and flavor inherent to the raw ingredients. There is great emphasis placed upon the aesthetic properties of food in Cantonese cuisine, and there is a lot of attention paid to contrasting colors, textures, tastes and scents of each dish. The Cantonese are particularly known for their stir-fried dishes where brilliantly hued crisp vegetables contrast with meltingly tender meat, which are often enhanced with one or two judiciously applied condiments like light-colored soy sauce or fermented black beans.

As a whole, Sichuan food is all about building flavors with many layers, and creating many different textures with different cooking techniques, but without regard to the natural colors of the ingredients. Many Sichuan dishes are muddy in color, and lack the kaleidoscopic color variety that is present in Cantonese food. By contrast, Cantonese food favors purer, more simple and clean flavors, which are no less satisfying for their lack of complexity, and the colors of each dish provide a delight to the eye as well as to the palate.

Interestingly, last night turned out to be an experience that perfectly illustrated the answer I gave to my student.

After the class was over, while we were cleaning up, I tasted the foods that I had prepared, along with my four assistants and some other employees of the Sur la Table store. I cook these dishes often at home, and so I was not surprised to find that they were really good. They were intensely flavored, which illustrated the layered effect that the use of many different condiments and unique ingredients that Sichuan food is known for. Zak had come to pick me up and he had a taste as well, and said that the Ma Po was particularly good, though I myself, was fond of the Too Hot Chicken and the green beans.

We planned to go to a local restaurant which was open late for supper; it had been suggested to me by one of the students from Grace Young’s class, a man who teaches Chinese cooking in a local high school as a special part of the home economics and social studies curriculum. We had stopped in for dim sum a few days before and were very impressed with the quality of the taro dumplings and turnip cake, as well as the steamed lotus seed buns. We had been told that they had two menus and that the Chinese menu was superb.

We were not led astray.

We sat down and set aside the silverware, and the woman who handed us both the Chinese and American menus said, “I see you want chopsticks.†She then brought out two sets of chopsticks, the homemade chili oil with seeds and a small dish of sliced fresh jalapenos in a dark soy based sauce, along with a pot of tea. We ordered a small order of tofu and sliced pork soup, and I ordered chicken with bitter melon and Zak ordered beef with Chinese broccoli. When she heard our orders, her eyes lip up and she smiled.

She brought out the soup and it was a typically delicate Cantonese offering–a good homemade chicken stock with billowy cubes of extremely fresh tofu, rich black mushrooms, thin slices of sweet pork, greens, baby corn and straw mushrooms. The chicken stock was light and seasoned with a bit of white pepper, the baby corn was the most fresh and flavorful I had ever tasted and the greens, choy sum, had the buttery-smooth leaves contrasted with the crisp stems with their distinctive salt-tinged vegetal savor. The soup came in a communal tureen, and we were given small individual bowls with Chinese style soup spoons. The bowls were perfectly sized to fit in one hand, so I felt confident eating the soup in a Chinese manner, by drinking it.

When our entrees came out, a different waitress brought them. Setting mine down, she declared, “You sure know what to order! This is the best dish on the menu–it is my favorite.†When Zak’s dish came moments later, we both dug in, cupping our small rice bowls in our off-hands while plucking morsels from the central platters with our chopsticks.

Both dishes were perfect examples of Cantonese restraint in seasoning and mastery of the wok. The chicken with bitter melon was seasoned with fermented black beans, a bit of thin soy sauce and some chicken stock, and was utterly sublime. The meat was filled with wok hay, that savory fragrance that only comes from being cooked in a well-seasoned wok on high heat and then rushed to the table before it can dissipate. The salty black beans accentuated the rich flavor of the meat, and coaxed out the natural sweetness that lays hidden in the heart of the bitter melon. Without that slightly smoky saltiness of the black beans, the bitterness would overpower the watery hint of sugar present in the fruit.

Zak’s beef with Chinese broccoli (gai lan) was a lovely dish, too. The gai lan was a provided a great contrast to the bitter melon; the broccoli was crisp where the melon was velvety, it was sweet with the slightest hint of bitterness while the melon was the opposite, and it was vibrant emerald green while the melon was the muted shade of celadon. The pale chicken breast meat slices contrasted with the meltingly tender richness dark beef slices; the two dishes complemented each other perfectly.

It was a meal of perfect yin and yang balance.

And in retrospect, I realized that the entire evening was a study in the balance of opposites.

Halfway through the meal, our original waitress came to check on us and refill our tea. Seeing me holding my rice bowl and eating casually in a Chinese way, she blinked and asked if I was from New York. Smiling, I shook my head and said, “No, I’m from West Virginia.†She blinked again and said, “Oh.†Then she paused and said, “I wondered, because you eat like a Chinese.â€

I explained that I had worked in a Chinese restaurant, and she nodded, satisfied with my answer, though I suspect, still a bit confused. When she caught sight of my jade and gold wedding band, she commented on it, and smiled. Another contrast, another balance. A West Virginia farm girl wearing jade and teaching the cuisines of a completely different culture.

I wish that I could have brought all of my students from my Sichuan class there to eat, so they wouldn’t have to just take my word on the differences between Sichuan and Cantonese food. They could have tasted those differences directly, and would have had a perfect, unforgettable object lesson in the importance of balance and contrast when it comes to Chinese cookery.

The Chinese Cookbook Project

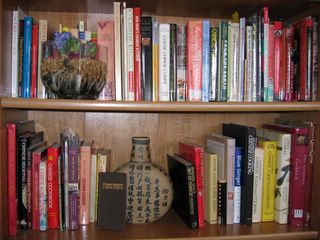

The beginnings of the Chinese Cookbook Project

It all started with my daughter.

She wanted to learn to cook Chinese food. And she wanted a wok and a rice cooker of her very own for Generic Winter Holiday.

Now, if she lived with me, all of this would be much simpler. She wouldn’t need her own rice cooker, because she could use mine; she could have her own small carbon steel wok and she could learn to cook Chinese food the best way–at my elbow.

But, since she doesn’t currently live with me, this posed a few interesting challenges.

I ended up getting her the wok and rice cooker, a pair of pretty good kitchen knives, some silicone prep bowls that she cannot break, a garlic peeler, a wok shovel and some rice paddles.

That just left the problem of a cookbook.

I wanted to get her a really good cookbook for absolute beginners that taught not only the hows of Chinese cooking, but the whys. She not only needed to know how the techniques worked together, but why they fitted together so well into a seamless whole of cuisine theory. The Chinese have been cooking, eating, and writing philosophical treatises on such since the time of Confucius. Indeed, the great philosopher was himself an epicure, and gastronomy is considered so highly that many Chinese scholars, ancient and modern, discourse upon the subject in their works.

In addition to the aesthetic and scientific principles of cookery, there is an entire underlying layer of meaning to Chinese food that has to do with the subtleties of health and physical energy, known as chi. As in tai chi, the Chinese martial art that has to do with moving the natural physical energy in the body in such a way as to bring harmony to the body, mind and spirit. Chi is the same things as hay in Cantonese–as in wok hay. And it is understood by the Chinese that food and eating are both integrally involved in one’s physical, emotional, and spiritual health on a subtle, energetic level.

I believe that all of these principles are extremely important to understanding Chinese cooking, and I try to at least expose my students to these ideas so that they get a good foundational understanding of the concepts behind the dishes I am teaching them. When I have taught private students, or when students take an entire series of courses that I teach publicly, they tend to get a deeper understanding of Chinese cookery as a holistic art that touches upon every aspect of Chinese culture and life. I wanted to help my daughter, who is turning fifteen in a few days, to get a foundational understanding of these principles while she learned to cook the dishes she enjoys from my kitchen and in various restaurants.

So, I started by looking through my rather large collection of Chinese cookbooks for a book to start a teenager down the path of learning to cook and eat in a Chinese manner.

And I discovered something.

There are some really great books in print that teach various Chinese dishes, and some of them teach the techniques well for beginners, but none of them really go in depth on the “whys†that form the essential logic and philosophy of Chinese cookery. Some touch on the healthy aspects of Chinese food, and other books do well at teaching physical techniques, but not many are well-illustrated to show how the techniques should look in practice. Chinese cookery is very technique-heavy, with a great deal of emphasis on very precise cutting in preparation for stir-frying, that it is difficult for an inexperienced person to grasp these without pictorial references.

I was lucky when I started learning Chinese cooking; I had the experience of watching a variety of trained Chinese chefs working in the kitchen with Huy. I had seen them do all of the various cuts and had watched them prepare meats for roasting and had even helped with some preparation, like filling wontons or wrapping spring rolls. And of course, there was always Martin Yan on television, so I could easily learn how to use a Chinese cleaver or how to dry fry from a book that had few or no illustrations. I had already seen these actions performed and had them in my memory.

I reluctantly ended up picking up Chinese Cooking for Dummies by Martin Yan, (what an unfortunate title) because it gave a very good step-by-step explanation of the fundamentals of Chinese cuisine in a way that was simple enough for an inexperienced cook to understand. There were very few photographs, but there were a lot of line-drawings show how to hold the knife and how various cuts should look. I also picked up, much less reluctantly, Yan-Kit So’s Yan-Kit’s Classic Chinese Cookbook, which is lavishly illustrated with full color photographs, not only of the finished dishes, but of ingredients, tools, and the techniques of cutting, steaming and stir-frying. The text is also written in a manner which I find to be very beginner-friendly, which is good for someone like my daughter, who is, unlike her mother, not in the habit of reading cookbooks for the sheer joy of it.

Books that I rejected out of hand because they were too densely written for someone with the patience level of a fifteen year old included Barbara Tropp’s The Modern Art of Chinese Cooking. It pained me to not give her that book, for it is a well-loved classic in my house, but I knew that Morganna would not have the patience to delve into some of the rather dense and dry prose that Tropp uses to explain the complex techniques and philosophy of the Chinese kitchen. I also turned aside Gloria Bley Miller’s doorstop classic, The Thousand Recipe Chinese Cookbook, which was the second Chinese cookbook that I owned, because it had very little in the way of useful illustration and too many of the recipes were simple variants of each other. I knew that if she had a volume of that size to dig through, my daughter might never pick up her wok and start to cook.

That is when I started looking at some of the books that I have which are out of print. Irene Kuo’s classic, The Key to Chinese Cooking has a nearly perfect balance of technical information and philosophical background, and once I picked it up, I began re-reading it for the pleasure of it. Her prose writing style gives the feeling of having an old friend whispering instruction into your ear, as you embark upon your adventure in the kitchen. Grace Chu’s Cooking School by Grace Zia Chu is similarly informative and comforting; both of these women were accomplished cooking instructors who worked primarily with American students, so they really can get to the heart of how to explain the complexities of Chinese food to people who were not born to that culture. Another great teacher whose books are all sadly out of print is Florence Lin.

As I read these older books, I began to realize that there was a lot of information out there that is just not available to modern students. Unless they are interested in digging around in used bookstores, or if they know what they are looking for, hunting up titles available online, few beginners will have heard of Grace Zia Chu, Irene Kuo or Florence Lin. The books do not look like much by modern standards–they are not full of photographs, and there aren’t a lot of line drawings, but the information is all presented in such no-nonsense, practical ways that I cannot help but see them as jewels hidden by the whims of the publishing world.

As I looked at these books, and traced their pages lovingly, I began to think beyond the plight of my daughter, and began to realize that the words of these great teachers might be lost to those who could benefit from them most. I remembered my experiences at Johnson & Wales culinary college, and remembered the way in which the cuisines of Asia were presented.

Culinary colleges in the United States teach the French principles of cuisine that were set down by Escoffier. It makes sense, since Escoffier was essentially creating an efficient method of running a restaurant kitchen, and also because much of American restaurant practice and culinary lineage comes directly from France. This is all fine and sensible, however, it means that the other cuisines of the world, particularly non-European ones, suffer from a lack of time and attention to cultural detail.

When we took “International Cuisine†which covered all the other cuisines of the world that were not covered in the classes “French Classical,†“American Regional†and “Continental Cuisines,†the whole of the continent of Asia was taught within three days of the nine day class. Three days spent on Chinese cuisines alone would not even scratch the surface of what there is to learn about even the basics, much less the complexities of the subject.

In addition, the library section on Chinese and other Asian cuisines was woefully inadequate. I did better relying on my own library at home when writing papers or researching recipes.

As I held these books in my lap and reminisced, an idea formed.

Why don’t I put together a library of both in print and out of print Chinese cookbooks, gathering together as many of the significant works I can find and then, at some point in the future, bequeath the collection to Johnson & Wales so that these books would be available to young students for generations to come?

I liked the idea well enough that I posted about it on a message board that an acquaintance of mine runs on his website. I figured that the posters in that community could give me suggestions on what books I should seek out and point out good leads on booksellers. Well, Gary Soup, the administrator of the site, liked the idea so much he gave me my own forum and we emailed back and forth to talk about which books he thought would have great historic significance that I should seek out.

At this point, I thought it might be best if I let my husband, Zak, know what is going on. He was up in his studio working on art, and so had missed all of the excitement that was happening downstairs, in my head, and on the Internet. So, over dinner (I believe I cooked him something particularly good, like Ma Po Tofu), I let him in on my cunning plan. He thought it was interesting, especially after I told him that I had the thought of attempting to unravel, then piece back together and record the history of Chinese cookbooks published in English. We both get bright-eyed over history, the more esoteric and generally odd, the better. So, the Chinese Cookbook Project was born.

One of the cookbooks that Gary suggested I pick up because of its historical significance is a very old one, called simply Chinese-Japanese Cookbook, written by Sara Bosse and Onoto Watanna, and published by Rand McNally in 1914. Gary has a link to an electronic archived edition of the book, and while it is not the very first Chinese cookbook printed in English in the United States, it is among the first handful.

Another book that the posters on the forums suggested I acquire was Florence Lin’s Complete Book of Chinese Noodles, Dumplings and Breads. That was one of her books I -did- not have, but which I heard raves from everyone who mentioned it.

So, I set forth. I had no belief that I would find a copy of the first book, being as it was so old, and even if I did find one, I assumed it would be prohibitively expensive. Oddly enough, within days of Gary’s suggestion, I looked it up on ebay and lo and behold–there was a copy listed, with the ridiculous opening bid of ninety-nine cents. Yes. You read that correctly.

I am not generally a superstitious person, but I have noticed that when I am doing something that seems to be “right,†or in line with what the Universe seems to want from me, small coincidences occur which make my endeavor start to fall into place. And this was one of those times. It was rather spooky, really, coming across this book on ebay within days of deciding to start this collection as a project that reached beyond myself and my own edification.

So, I watched the auction for several days. There were only two people bidding on it, and they seemed inclined to bid fairly low. I waited until the last five minutes of the auction and bid high, and picked up the book for a very small sum. Very gratified, I set my sights on the Florence Lin book.

Which I discovered to my dismay, is a highly sought after book, and is very expensive. Some copies go on ebay, Amazon or through Bookfinder for one hundred dollars or more. I couldn’t find a copy anywhere for less than seventy dollars. I was disheartened.

But, oddly, one evening after reading my email, blogs and message boards, I decided to check for the book on Amazon one more time. And there was a new listing for a used copy of it from Alaska, of all places, for the paltry amount of seventeen dollars.

Before you can say “gong hay fat choy,†I hit the “Buy this now with one-click†button, and lucked into a very well-cared for copy of the book.

So now, I am in the process of cataloguing the books I currently have. I have also been compiling a list of books that I am seeking. In the meantime, many little adventures in online book hunting have happened that I will relate in later posts. I also intend to write about what I have learned of the history of Chinese cookbooks published in English, as well as reviews for many of these books.

For now, let it suffice for me to say, that the Chinese Cookbook Project is well in hand and underway.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.