Author Peter Singer Critiques the Practice of Eating Locally

Zak sent me a link this morning to this Alternet article covering ethicist Peter Singer’s new book, The Way We Eat: Why Our Food Choices Matter, because he thought I would probably be interested in what he had to say about eating locally.

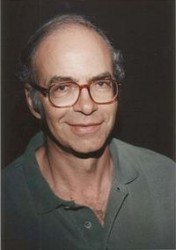

And I was. Singer is probably best well-known as the author of the 1975 landmark book, Animal Liberation, a volume which helped kick-start the animal rights movement and turned many carnivores into vegetarians. The Ira W. DeCamp professor of bioethics at Princeton University, and laureate professor at the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics, University of Melbourne is considered to be a “practical ethicist,” basing all ethical considerations and constructions upon concepts of utility. Every action is examined under the completely objective lens of how much suffering the action will cause. Singer asks us to contemplate, “What is the best consequence this action can have?” before we take that action.

I feel rather silly, in fact, taking this 30-year veteran ethicist on and disagreeing with some of his points, since I am no philosopher, nor even ethicist, but I can’t help it. While I agree with much I have read of his opinions, not only in Alternet’s “It’s Not Enough to Be a Vegetarian,” but also the recent Mother Jones interview, “Chew the Right Thing,” and Salon.com’s “The Practical Ethicist,” I do not agree with all of his statements on eating locally, because he just does not make his case as well as he thinks he does.

When the Mother Jones writer asked him about the ethics of eating locally, here is what Singer had to say:

“You have to ask yourself what’s particularly good about being local. People say, “Well, I want to support my local economy.†But if you’re living in a prosperous part of the United States, what’s really ethical about supporting the economy around you rather than, say, buying fairly traded produce from Bangladesh, where you might be supporting smaller, poorer farmers who need a market for their goods? So I think that just in terms of supporting your local economy, I’d say no, you should support the economy where your dollars are needed most. But then people will say, “Yes, but there’s all the fossil fuel used in shipping it over from Bangladesh or wherever.†But people often don’t realize that if you’re shipping something like rice by sea, the fuel costs are extremely low. Shipping is a very efficient way of transporting. It may be that if you’re buying rice in California, the rice from Bangladesh has used less fossil fuel than California rice, even counting what it takes to get there. We also found that when we looked at tomatoes produced in New Jersey early in the season by being grown on heat, when you calculate the amount of oil that goes into heating the greenhouses, it turns out that you could have trucked them up from Florida with a similar amount of oil. If people are prepared to eat locally and seasonally, then they probably do pretty well in terms of environmental impact. But there’s not many people who live in the northern states of the U.S. who will say, “I’m not going to have any tomatoes between November and July.†So I think there’s a certain amount of double talk about local food that’s just too rosy.”

First of all, let’s examine this very wide-ranging answer point by point.

First, Singer assumes that he is talking to a person who is living in a prosperous area of the United States, when he says that we are better off ethically giving our money overseas to a Fair Trade farmer in Bangladesh than supporting already affluent rice farmers in California. (For the record, I buy imported rice, and agree with Singer’s points about California rice being grown unsustainably in fields artificially flooded by water piped in from other states, thus draining aquifers unnecessarily.)

However, I don’t live in an affluent area of the United States.

I live in one of the poorest counties in Ohio, where 51.9% of the population and 14.8% of the families live below the poverty line. Now, I reckon that by Bangledeshi standards, our farmers in Athens County are still rich, but the US is not Bangledesh. Not everyone in the US is living well, and I would like to support the people in my own community who are helping to provide good food that is grown sustainably and healthily with my money. Remember the catchphrase, “Think globally, act locally?”

Besides, shopping at my local farmer’s market does not preclude me from buying non-locally produced Fair Trade food products. Just a few seconds ago, in fact, I was nibbling on a bit of Fair Trade Certified chocolate, while my (decaf) morning coffee was shade grown Fair Trade organic Cafe Mam from Mexico.

On to Singers next point.

We also found that when we looked at tomatoes produced in New Jersey early in the season by being grown on heat, when you calculate the amount of oil that goes into heating the greenhouses, it turns out that you could have trucked them up from Florida with a similar amount of oil.

So, my answer to this is, “Don’t buy those crunchy, unseasonal tomatoes, dude. I don’t.” And I don’t. Nor do I buy them from Florida, because, frankly, whether they are grown hydroponically in a greenhouse in the winter or picked green in Florida and shipped north in refrigerated trucks, they taste like nothing, and why pay money for nothing?

Singer further remarks,

If people are prepared to eat locally and seasonally, then they probably do pretty well in terms of environmental impact. But there’s not many people who live in the northern states of the U.S. who will say, “I’m not going to have any tomatoes between November and July.â€

Okay, well, here is one of those “not many people” who refuses to eat “fresh” tomatoes between November and July, standing up, waving her arms and demanding to be counted by Singer and others.

I hate unseasonal “fresh” tomatoes, so I don’t buy them. Not at the farmer’s market, not at the greengrocers, not at Whole Foods, and not at the grocery store. I don’t give a darned if they are grown in Ohio, Florida, New Jersey or Holland, I am not buying them because they taste like utter crap. If I want tomatoes in the winter, I buy them canned, thank you. (Or I use the ones I froze myself during the summer glut.) They taste better than unseasonal ones and contain more nutritional value than the faux fresh ones in the marketplace in the winter.

One of the entire points of the Eat Local movement that Singer is either ignoring or is unaware of, is the principle of seasonal eating. We eat our fresh food in the season it is meant to be enjoyed, when it is at the peak of ripeness, when it is full of flavor and nutrients and when it really does cost less in energy to produce and bring to the “local” market. He can think that there is a “certain amount of double-talk about local foods that’s just too rosy,” but he is commiting the fallacy of making sweeping generalizations and painting an entire group of quite ethical eaters with a very broad brush.

I expect a better argument than that from the Ira W. DeCamp professor of bioethics at Princeton University and a man who is considered to be a “professional ethicist.”

At the end of the Salon article, the interviewer asked Singer what advice he would give to readers who might want to change their dietary habits after reading his book.

This is how Singer answered:

Avoid factory farm products. The worst of all the things we talk about in the book is intensive animal agriculture. If you can be vegetarian or vegan that’s ideal. If you can buy organic and vegan that’s better still, and organic and fair trade and vegan, better still, but if that gets too difficult or too complicated, just ask yourself, Does this product come from intensive animal agriculture? If it does, avoid it, and then you will have achieved 80 percent of the good that you would have achieved if you followed every suggestion in the book.

I am so with Singer when he says, “Avoid factory farm products.” I do avoid such products, and I will continue to urge others to do so, as I have done for years. The practices of industrial farming are cruel, unhealthy, unsustainable and in the end, produce a lower-quality product that may be harmful to human health.

I also will not argue with him when he says, “If you can be vegetarian or vegan,” that’s ideal, although I think that statement is not as absolute as he makes it out to be. I believe it is perfectly possible to be an ethical omnivore and eat some amount of meat, but I will give Singer that statement free of charge and let him make his request, because frankly, lots of folks eat more meat than is necessary, and if they slowed down a bit or stopped, it is probably not a bad thing.

However, when he says, “If you can buy organic and vegan, that’s better still…” I catch my breath and shake my head.

Because there is an inherent problem in that statement, one which I do not think that Singer, or many other vegans are aware of.

In choosing to buy organic food, which is arguably much better for the environment, they are supporting the meat industry, albeit indirectly.

How can this be, one might ask? Read on.

What exactly makes food “organic?”

It is grown without artifical, petrochemical-derived pesticides or fertilizers.

Okay.

So, where do the fertilizers for organic foods come from?

Animal manure. Specifically herbivorous livestock manure. Such as the stuff that comes from cows, sheep, goats, ducks, chickens and (admittedly omnivorous) pigs.

That is the flaw in the popular argument that if we fat Americans all just became vegans, the world would instantly be a better place, and animal suffering would end, and uh, all that horse-hockey. Because many vegans also are consumers of organic foods, and great supporters of organic agriculture as being more sustainable, I cannot help but wonder what kind of fertilizer they expect farmers to use if there are no more cows, chickens, pigs or sheep being raised for meat, eggs or milk.

There are other statements in those articles that Singer makes that I take issue with. It seems that he is against any sort of confinement for chickens, including rolling outdoor pens with open bottoms so they can scratch in the grass, eating bugs and plants, because such pens, even though they give ample room for the birds to move around and engage in natural behaviors, are, to his mind, too small. A few of his statements sound as if he is against egg farmers keeping chickens in coops with protected yards, too. I cannot help but wonder what kind of sense this makes since chickens have no real way to protect themselves from predators such as foxes, coyotes, bobcats, and even worse, feral dogs. (The former three animals tend to just kill to eat, so they take one or two chickens at a time, while feral dogs will tear apart a whole flock just for the fun of it. Believe me, I have seen it happen.)

I just want to say to Mr. Singer, “Sir, sometimes hens are confined to protect them from being killed by predators.”

I just get the feeling that Singer doesn’t understand that many small farmers feel very attached to their livestock, and care deeply about them being hurt, not because it hurts the bottom line, but because it is really awful to come home and see the devastation of a bunch of chickens torn to pieces senselessly in your front yard.

I don’t think Singer has spoken with very many small farmers, like the man I buy chicken from at the Athens Farmer’s Market. He told me about a flock of chickens he lost in an outdoor pen this winter, because the prevailing wind shifted, and was not blocked by the solid sides of the pen as usual. Instead, during a storm, the wind came from the opposing direction, swooping through the chicken wire, causing the chickens to huddle together for warmth. They suffocated each other before the farmer got to them.

When he related this sad story to me, the grief in the man’s face was obvious. “Those poor birds,” he said. “It made me sick to lose them that way. The poor little things.”

These are not the words of an unethical man who is not concerned witih the welfare of the animals in his care.

While I agree with his vehement arguments against CAFOs, feedlots and factory farming practices, I cannot help but think that Singer’s experience with the ways in which smaller, local farmers live and work is limited. I also feel that he either is ignorant of or ignores the nuances involved in the movement to eat more locally and sustainably.

That said, I did just order a copy of his book, so be prepared for a long review of it here on this blog sometime in the near future.

24 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.

I read that article on alternet this morning and thought to send you a link, but remembered that Zak usually beats me to it. So instead I waited to see if you would write about. Lo and behold here it is.

Thank you for the insights. I always enjoy reading your more political/opinionated posts just as much as your posts with the food you have cooked. : )

Comment by Benjamin — May 23, 2006 #

very insightful, thank you for taking the time and effort to write this.

sam

Comment by sam — May 23, 2006 #

I really enjoy reading the esaays you post here, I personally find them very insightful.

Another thing I think Singer wasn’t considering is what economists like to term “imperfect information.” There is always something you may not know about the food you eat, but with local it is lessened. There is not better information than that gleaned from actually asking a farmer or observing the farm. In economics, well, that is a good thing, it leads to efficiencies such as having your purchase reflect wha t you actually demand.

Comment by melissa — May 23, 2006 #

Manure is why I can’t see veganism as sustainable in the long run. Vegan farming would rely on petrochemical fertilizers, which are not sustainable, unless they could somehow produce sufficient amounts of plant compost sustainably (but even then, is using earthworms truly vegan? I’m not sure, but I’ve met some vegans who would oppose earthworm use).

I just can’t think of a way to farm sustainably without animals, especially since the most sustainable small farms use animals to pull the plow as well. I went to the Land Institute’s PrairieFest last year and there was an Amish farmer and writer there who was amazingly inspiring about food and sustainable farming–it just…wouldn’t work without the animals.

Comment by Mel — May 23, 2006 #

Thanks for this. Interesting post. I have to say that while I generally support the Eat Local movement, I do think that the rhetoric can do with some more measured perspectives on what “local” means, and the implications and effective reasons for those choices. So I do like that part about what he’s saying. I hear some really dubious reasoning/math going ’round about oil consumption and environmental impact.

This said, I share a lot of your concerns about his work. I also echo your support for the small humane farmer who has both crops and livestock. I grew up in a small farming family & am often irritated by the lack of both empathy and respect that seems to bleed in around the edges when people talk about food production in relation to the small farmer.

Comment by frumiousb — May 24, 2006 #

“I cannot help but wonder what kind of fertilizer they expect farmers to use if there are no more cows, chickens, pigs or sheep being raised for meat, eggs or milk.”

This is just a thought, but human manure has been used throughout history and in many cultures as a fertilizer.

If I do a quick Google for “human manure” there’s a lot of information out there on how this can be composted and used safely.

Comment by Mae — May 24, 2006 #

Barbara, as usual a very interesting analysis. The more I read your pieces, the more I realize I don’t know!

Keep up the good work!

Comment by Meg — May 24, 2006 #

“Okay, well, here is one of those “not many people†who refuses to eat “fresh†tomatoes between November and July, standing up, waving her arms and demanding to be counted by Singer and others.”

And here’s another. I agree, out of season tomatoes are sad, depressing things, in season they’re delicious. Winters can get long and depressing here in Minnesota, why have sad, tasteless tomatoes around to make it worse?

Comment by Megan — May 24, 2006 #

Hey, Benjamin–Yeah, Zak was on the ball again, and sent it first thing in the wee early morning to me. And, I -had- to read more of what Singer said, and then talk about it. Just had to.

Thanks, Sam!

Melissa–no, he is not seeming to take into account imperfect information in his equations. Also, you are so correct with having the power of consumer demand on the part of the purchaser–the farmers here, if you ask them to grow something–will do it. That is how we have so many Asian vegetables growing here!

Mel–There are other fertilizers that could be used for organic farming–Mae hits on one, but unlike what she says, there are issues to the use of human manure as a fertilizer–I will look at those in a moment. One could use composted plant matter exclusively instead of using petrochemicals, but it would take a large industry in making this compost efficiently to amass enough of it to use for the amount of growing that we would be doing.

frumiousb (Bandersnatch?) I agree that the Eat Local movement is lacking in deep philosophical rhetoric. On the other hand, is it really necessary to have that to get people into the idea of eating locally grown produce in season? Think about it–it is the way that we used to eat anyway–up until the 1940’s, in fact, much of our food was locally produced in the US. Factory farming didn’t really kick into high gear until after WWII, after all.

Do we need philosophy in order to capture people’s imaginations and taste buds? That is a good question, and one I haven’t answered.

I did like that Singer made me think, though I was disappointed at how easily some of his thoughts on local food were dismantled by an “amateur ethicist’s” casual arguments. I expected a stronger, more watertight statement out of the man who converted thousands to vegetarianism!

Oh, and one thing–there is no such thing that I can find online as Bangladeshi free trade rice. He made that up. However, I did find some Thai jasmine free trade rice and bought it, even though it was expensive. Money isn’t everything….

As for his disrespect for small farmers–that bugged me big time, too. My grandparents farmed as did my great grandparents, and they were highly ethical people, so it bugged the crap out of me that he didn’t seem to have much knowledge or sympathy with how small farmers operate and how they feel toward their livestock.

Well–we will see about his book when it comes!

Mae–yes, human manure -can- be used safely. But, throughout history, it has -not- always been used safely, and one has to monitor the heat of it as a composts -carefully- in order to make certain that all pathogens that come out of our guts are killed.

Ever wonder why the Chinese do not traditionally eat raw vegetables? Because they use human manure, called “night soil” on their vegetable crops and have done so for thousands of years. They, therefore, do not eat raw vegetables–they are always at least blanched before consumption. Otherwise, disease would be spread through eating uncooked food.

There are a lot of diseases that can be carried in human excrement–cholera, and dysentery are two, and human e coli is nothing to sneeze at. My issue with the use of human manure is this–do I trust corporate farming conglomerates or chemical fertilizer companies, which have to this point shown very little regard for farmer or consumer safety and health to safely compost human manure such that it can be used on our fields without harm?

The answer is–no. Not really. No.

I am not ignorant of human manure–in fact, it is going to feature prominently in an essay on why I don’t think that veganism on a large scale is particularly sustainable. You are right–it -can- be used safely, but it is not the panacea that you are suggesting. Herbivorous manures are much safer in the short and long term.

Meg, thank you. I will keep writing!

Comment by Barbara — May 24, 2006 #

As always Barbara, you inspire me to live a more eco-conscious life.

Comment by KCatGU — May 24, 2006 #

I really appreciate this thoughtful analysis.

I’d also like to point out that Mr. Singer is indicating that we should completely neglect our own local economy and our local farmers in favor of those overseas. This is both foolish and incredibly short-sighted.

Comment by Amber — May 24, 2006 #

Barbara, thank you so much for your exploration of things like these – I enjoy your commentary and perspective so much.

Ah – Peter Singer… At the risk of sounding reflexively reactive, let’s not forget that this is the same writer whose focused utilitarianism leads him to say that infanticide up to the age of, I believe, 9 months is perfectly logical – if a child will not benefit society then why keep it? However, he is also a man who lives simply, advocates many charitable causes, and gives away a great deal of his own personal income. To me, these seeming contradictions show fundamental problems with utilitarianism as a practical, guiding worldview; he seems bent on following through with it as intellectual experiment, taking it to its most severe and logical edges. Kudos to him for living consistently with his worldview; it just isn’t one, I think, that will stand up over time.

Oh, and count me in as one who won’t buy the pink fluff out of season tomatoes. If it doesn’t smell like a tomato, then I ain’t buying. Right now you can smell the piles of tomatoes at the greengrocers near my house before you walk in the door. Spring in Florida… Yum yum.

Comment by Faith — May 25, 2006 #

Hi Barbara,

I have to wonder about the following:

“I buy imported rice, and agree with Singer’s points about California rice being grown unsustainably in fields artificially flooded by water piped in from other states, thus draining aquifers unnecessarily.)”

I live in Sacramento, the top of the San Joaquin Valley, and am surrounded by rice fields. This is where most California rice is grown. As far as I know, we get all of our water from the Sierras. Counties north of us may get water from the California sections of the Cascade and Klamath mountain ranges. On the other side of the Sierras is Nevada, and below that, Arizona. Not big water states. See Rice Production in California from UC Davis.

The issue in California regarding water is piping it from Northern to Southern California in the Aqueduct. Southern Cal takes Northern Cal water, a lot of it. The water that the city of Los Angeles alone takes has substantially changed the farming economics in the land surrounding streams that are now dried up because the water is diverted into the Aqueduct.

Yet the biggest rice growing region is right up here, not down South. We have tons of water. We are in a flood zone. This is why the rice fields are here. No shortage of water. Never been a shortage of water (except 2 drought years in the 70s).

So, I don’t get Singer’s point at all.

Comment by Elise — May 25, 2006 #

I am glad that my essays are inspirational to people, helping folks be more conscious of what they eat and how they eat. There is no greater reward for any writer than finding out that something that she has written has helped changed the way a person thinks, lives or interacts in the world.

Amber–I agree with you. I also note that Singer is assuming that all farmers in the US are “well off.” This may be true of larger producers of rice or other commodities, but I doubt it. The farmers who grow corn in the US, which is arguably the biggest food commodity in our county when it comes to volume and money it makes for the fast food and processed food industries, are NOT making huge amounts of money. In fact, a lot of them are struggling to break even, or keep their heads above water. In fact, suicide is one of the largest causes of death among farmers in the US–so I am not sure what “rich” farmers Singer is talking about.

Which makes me look upon his opinions somewhat askance. I think that his grasp of fact may not be as tight as he thinks it is.

Yes, Faith, that is the same singer. And no, I don’t think that his utilitarian ethics are necessarily particularly useful or humanizing. In fact, some of his logic comes very close to the logic that the Nazis used to exterminate the disabled and the mentally ill during WWII.

Anyone whose ethics even come close to being similar to anything the Nazis cooked up gives me goosebumps,and makes me take anything that the person says with a mine of salt.

That said, I do agree with him that CAFO meat is cruelty on a incarnate.

Elise–that is an excellent point.

When I was thinking of California water coming from other states–I was thinking of southern California, not Northern California. So, Singer’s point–how valid is it?

In fact, if he gets his facts about how California rice is grown wrong, if he isn’t cognizant that many US farmers cannot make a living farming, and he makes up his example of Bangladeshi Fair Trade Rice–how factually based are any of his opinions when it comes to local eating?

And if his opinions on that subject are so tangentially based in reality, what of his other ethical arguments on other topics?

I can’t wait until the book comes in, because I -really-want to read it now.

Comment by Barbara — May 25, 2006 #

“I cannot help but wonder what kind of fertilizer they expect farmers to use if there are no more cows, chickens, pigs or sheep being raised for meat, eggs or milk.â€

A vast number of highly effective organic fertilisers are vegan (if not the vast majority).

-Kelp or other seaweed based products

-Compost – compostable plant material is far more readily available than animal manure, and if treated appropriately, works as a more effective slow release fertiliser. When you add in the fact that most of the nitrogen, nutrients etc are used by animals that eat plants, making fertiliser directly from plants is much more efficient, simple and cost effective.

-Compost teas, which can be fed into standard spray-rigs

-Allowing land to fallow, and regenerate its own nutrients

Wonder no more…

I’m neither vegan nor vegetarian, so I don’t place this post with any kind of anti-animal farming bent, but to claim that animals are a neccessary component of productive organic farming is simply untrue.

Comment by Alicia — May 28, 2006 #

“I don’t think that his utilitarian ethics are necessarily particularly useful or humanizing. In fact, some of his logic comes very close to the logic that the Nazis used to exterminate the disabled and the mentally ill during WWII.

Anyone whose ethics even come close to being similar to anything the Nazis cooked up gives me goosebumps,and makes me take anything that the person says with a mine of salt.”

Also equating one of the worlds most active, passionate and devoted campaigners against animal cruelty and human poverty with nazists is unbelievable.

The laziest way to debase someone’s argument is to undermine them personally.

You’re happy to place such a slur on someone who has dedicated his life to defending the defenseless. Because his views expressed in a magazine article don’t fit in with your precise ideology?

I’d rather not live in a world without Peter Singers’ “utilitarian ethics” and all of the triumphs they have created for animal and human kind. i.e. the elimination of widespread animal testing for cosmetics and other chemical products, and the regeneration of poor communities nation-wide through fair trade agreements.

You might want to be a bit more informed on the character that you are assassinating in future before making such offensive and libelous statements.

Comment by Alicia — May 28, 2006 #

Sorry, Alicia, but anyone who claims that infanticide is defensible up to nine months of age because the child is not contributing to society, which I have read in some of Singer’s work, -is- treading dangerously close to the Nazi line that since the mentally ill, the disabled and the infirm were not contributing to society, they could be exterminated ethically.

I didn’t say the man was a Nazi–you inferred that. Saying he is a Nazi is character assassination.

Saying that one of his utilitarian philosophical statements treads a little closer to some of the justifications Nazis used to kill others is just saying that his utilitarian philosophy, if taken too far, is not to my liking.

You don’t like that? Too bad. That’s my opinion.

And it isn’t libel if Singer said such a thing, which I have seen quoted and attributed to him in several places. If he said that infanticide for a nine month old is permissible and ethically defenseable, then my opinion is not libelous.

He might want to think carefully before he says such disgusting things.

As for his defense of the defenseless–what is more defenseless than a human infant? (Or an infant of any sort?)

That said–all of those non-animal based fertilizers are useful and are used, but they are not the majority of organic fertilizers in use. Most of them are based upon manures of one sort or anthother. Compost is great stuff–but the best fertilizers are made from plant matter mixed with herbivorous manures, well rotted. That gives a full range of soil nutrients and humus, both of which are necessary for soil health and vitality.

It just makes sense to use the waste products of animals -and- plants the way that nature intends them to be used–as food for microorganisms, and as a means by which to build and retain soil fertility.

Comment by Barbara — May 28, 2006 #

On the rice front, I think one of the more absurd rice-growing activities is going on here in Australia, where we grow rice in the middle of the freaking desert, and pump water from about half a state (and our states aren’t exactly small areas of land) away, when most of the states in this part of a country are still in major drought conditions.

So, in comparison, I think the rice-growing habits of most other countries are just dandy.

I find Singer a fascinating character. Given there’s an Ethics major shoved into my two-thirds-completed degree (two semesters to go … ), and being Australian, with teaching staff who’ve had considerable interaction with him, I’ve come across a fair chunk of his stuff. And yes, the basic flaw with utilitarianism is that there are points at which you need to make decisions about whether you follow through the logic of your ethos, or draw a line in the sand. In some ways, I think Singer’s tendency to always take the former path in his writing does a considerable amount to make people think about where that line should be drawn. I can’t say whether or not that is/was his intention, but it’s what I get from a lot of his work.

But I am an ethics major, so my GPA has a vested interest in me overthinking about Singer, among other things. 🙂

Comment by Jennifer — June 2, 2006 #

May 2006 Eat Local Challenge: Conclusions

So May has come and gone and the challenge is over. I’m afraid I wasn’t as energetic as I could have been seeking out new sources of local food. And I think the people at the market think I’m seriously nutty. (“Eet’s that woman who always asks whe…

Trackback by Too Many Chefs — June 4, 2006 #

Jennifer–what I like best about Singer, is that he -does- make me think about where that line needs to be drawn, and that he forces people to think from a logical perspective. I, too, value logic and rational thought highly, more highly than emotion, when it comes to many of my decisions, but what Singer’s works have taught me is that logic and emotion must be in balance! You cannot make decisions based soley on one or the other–you must utilize both perspectives in order to be truly ethical and fully human.

I actually think he is a pretty fascinating character, and the more I read of his work, even if I disagree with it, on rational or emotional grounds, the more I admire him for really pushing the limits.

But then, I admire people who push limitations outwards.

Re: rice growing in drought areas–yeah, you are right. That is just downright goofy. Not sustainable at all.

Comment by Barbara — June 9, 2006 #

Barbara, to paraphrase your comment about Peter Singer: “you do not make your case as well as you think you do”.

You clearly misunderstand what animal manure is, if you think that agriculture couldn’t be practised sustainably without it.

Basically, animal manure is recycled vegetable matter.

An animal’s digestive tract isn’t a magical source of vitamins and minerals or whatever else you seem to think it is. In essence, what goes IN is what comes OUT. You can get precisely the same result by composting vegetable matter, or using “green manure” crops.

Regards,

Sam

Comment by Samantha Madell — July 3, 2006 #

Um, Sam–I -don’t- think that animals’ digestive tracts are a magical source of vitamins. Yes, you -can- get the same results by composting vegetable matter (well, close to the same results) it is just that compost takes longer than manure, because manure is already partially broken down. (You still should allow manure to age or compost further–it usually has too much nitrogen and possible pathogens in it to use fresh.)

My point is this–where are you going to get all of the biomass–plant matter–in order to make enough organic fertilizer in a vegan fashion? Cut down trees? No–not a good choice? Gather all the fallen leaves from forests? A better option, however, then the forest suffers from a lack of humus made from the leaves that fall. You can use plant waste from farms–straw, cornstalks, bean plants that are finished producing–that sort of thing–but that isn’t usually enough.

Kelp was suggested by another commenter, but where are farmers in Ohio going to get kelp? There are no oceans nearbye.

One could cut grass and use that–one could use municipal lawn waste–but, only if no one used Chemlawn or other chemical treatments on their fields.

No–I am -not- ignorant, as you say–and the reason I didn’t make the case as well as I thought I did was because I didn’t make the case fully–it is meant as a topic in another separate essay. But, I -have- thought long and hard about this.

The reason that I think that animal waste, combined with plant waste (lawn clippings, leaf litter, cornstalks, etc) is more sustainable than -just- plant matter is because it is frugal, and local, the use of it is a perfect reflection of the way that natural systems work.

Grass-based farms have animals graze on land that is unsuitable for cultivation, while the farmer cultivates land that is arable. The animals’ waste products, along with the plant waste from the arable lands are then composted and used to fertilize the arable land. In addition the waste from the animals that falls in the pasture land enriches the soil of the fields, and better grass is produced. All of this takes place on the farm in a closed loop, with very little in the way of outside inputs.

Kelp would have to be purchased and trucked in–at a significant money and energy cost.

Modelling your farm as closely on naturally occuring ecosystems is more sustainable–and all naturally occurring ecosystems include animals and plants.

Animals make use of solar energy that we humans can not–they eat grass. That is a fact. They can do so on land that is not suitable for farming–that is also a fact. Animals do not -have- to be treated cruelly or raised in inhumane CAFO style feedlots. That is also a fact.

They can be raised ethically and sanely. They can be treated well while they live, and they can be killed in as painless and humane way possible so that their meat can be eaten by humans after they die.

These are also facts. I have witnessed it, growing up as I did watching how my grandparents farmed their land. They had a closed loop ecosystem going and it worked very well.

It -can- be done.

Vegan farming can also be done, but I am not sure that it could be done without significant cash outlay for fertitlizer produced off of the farm, or without significant energy cost in the form of trucking said outside-produced fertilizer onto the farm.

Comment by Barbara — July 4, 2006 #

Vegan farming is perfectly obtainable. You don’t need to confine and kill animals in order to get manure.

Comment by Stewart — December 20, 2010 #

[…] Bend’s “The Source” Weekly chimes in… | Eat EfficientlyEat Efficiently: The I’d-Rather-Not Cook Book | Mexican Hairless Breed InformationWeekly Dinner Menu Planning: How to Avoid Getting Fat | swell easy livingFriendly Atheist Tigers & Strawberries […]

Pingback by Eat Efficiently: The I'd-Rather-Not Cook Book | 7Wins.eu — January 8, 2011 #