The Key to Indian Cooking: Making Spices Friendly With Each Other

The more I cook Indian food, the more I realize how much more there is to learn. Every time I think that I have it all down, I find out something new, or I try something different, or I get an inspiration, or a read a book, and the curiosity all begins again, and I am back in the kitchen, cooking up a new batch of unravelled secrets.

And so it goes.

But I think that over the years of experimentation, cooking from books, eating foods of the Indian subcontinent in restaurants and private homes, talking with cooks from India, and cooking with them, that I have learned a few things about Indian cookery. And these few things I would like to impart to my readers, because one of the questions that comes up over and over in classes, in emails and on cooking forums is, “Why doesn’t my Indian food taste right? How do you make yours so good?”

The true answer is a complex, and long one, but what it boils down to is time and practice.I have spent a long time working and studying Indian food, and have cooked a lot of it, quite a bit of it for very demanding native palates. So, I learned.

But immense pressure is not needed to learn to cook Indian food well. I think the most necessary qualities for someone to learn to cook Indan food well is patience, the willingness to learn, and a palate that can be trained.

And here is where we come to my simple answer for learning how to make good Indian food: you have to learn how to make spices become friendly with each other.

And in Indian cookery, there are many ways to do this. There is no one “right” answer to the question of how to make strong flavors meld together. Myriad techniques to accomplish this have been developed in India over centuries, and not every cook uses each technique, but I think that the more you learn, the more fluent you will be in the language of spices.

Think of yourself as a diplomat of the kitchen. Your duty, is to be able to speak the language of both the “wet” spices: onions, garlic, ginger, fresh chiles and herbs such as fenugreek greens, curry leaves, cilantro and mint, and language of the dry spices: peppercorns, cumin, coriander seeds, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, ajwan, nigella, asafoetida, and chiles.

You have to recognize that each wet and dry spice speaks a slightly different dialect of their mother tongue, but there are certain commonalities of speech that unites all members of each group.

How do you learn to speak these languages?

By getting aquainted with each spice. And by this, I mean, learn its taste and smell, on its own, with nothing else.

When I teach Indian food in my beginner’s class, I open by passing around containers of the dry spices we will be using, as well as raw bits of the wet spices. I tell the students to smell each spice, and if they will do it, taste it as well. I always provide water for swishing out the mouth in between in order to cleanse the palate. I have found that when directed to do this–students are hesitant, but eventually, one brave one tastes, and then they all try a cumin seed here, or a mustard seed there. A bit of ginger goes into the mouth of one, and a brave one takes a sliver of chile.

I tell them that when they stock their spice cabinets in order to cook Indian foods, for them to take a notebook, and do the smelling and tasting exercise over again–and this time to write down their impressions in a notebook. I want them to record what they taste. How they feel. What they smell.

I tell them to go back a day later, and taste the spices again, in combinations of two, and write their impressions down again. I tell them to keep tasting, over and over, combining and recombining spices in tiny amounts, so they can learn the scents and flavors of the ingredients in their nostrils and on their tongues.

Every student has told me that my method has helped them immensely. In tasting spices in isolation and then in combination, they learned how to actually begin to taste individual spices in curry dishes in restaurants, much to their surprise.

Knowing the taste of each spice is like putting the key into the lock that will open the door to Indian cookery. It is the first step.

But one still has to turn the key.

That is where the various techniques of cooking spices comes in.

There are very few Indian recipes that actually use raw spices. In fact, I have not run across one yet. In every recipe, the cook is told to cook the spices in some way, shape or form. Even the garam masala powder that is sprinkled on a dish just before serving is made from spices that were roasted whole, and then ground.

Not only does cooking improve the digestiblity of spices, but it opens up their aromas and tasts, like flowers blooming.

The simplest way in which spices are cooked are in the pan, in oil or ghee, as a first step toward making a curry. If there are onions in the dish, they go in first, with a little salt, in order to help them release their moisture. Then, they are stirred as they cook slowly to a deep golden brown color. Then, other spices are added as called for in the recipe. Perhaps some whole mustard seeds. Or some slivers of fresh ginger and sliced chiles. Or some whole cumin. At any rate, these are stirred together with the onions until the onions are a deep reddish brown. (Here is where the key in the lock turns a quarter turn–brown your onions deeply for many Indian foods, unless directed by the recipe otherwise. Most Americans are too timid about the onions. We tend to cook ours no more deeply colored than a golden brown. That will make a weakly flavored sauce. Keep going until those onions are a rich reddish brown. Just keep stirring and if they start to turn black, take the pan off the fire, and cool it immediately–dumping out the onions into a bowl to cool off if you have to.)

Once your onions are almost reddish brown, add any ground spices or spice paste and keep stirring until the onions are reddish brown and the whole room is fragrant with the delicious scent of spices mingling in a hot pan. The key has turned another little way.

Notice what we have done, in cooking the spices in hot oil. We do it in stages. We don’t dump all the spices in at once. There is a method to this–it is called “building flavor.” Gradually putting the spices into the dish in a certain order allows the maximum amount of flavor bloom to occur in the hot oil, without the spices burning. If we put the onionss in the pan, and then just threw in the garlic and the mustard seeds and the chiles and cooked them at the same time, the garlic and mustard seeds would burn before the onions were browned enough and the chiles would probably overextract and be very overpowering.

But putting them into an order, and layering the flavors in is a way of introducing these strong flavors so they can start building a beautiful friendship together.

Once the spices are cooked together in the pan, one can either take them out and grind it all into a paste, or leave them as they are. This depends on whether one is making a smooth curry sauce, or a more rustic sort of chunky curry. Pureeing the spices and cooked onions brings a body to the sauce, which improves the mouthfeel and the flavor of the finished curry.

In either case, the ingredients that will make the sauce are added, and the dish simmers.

The key is getting ready to turn again: the longer the flavor is simmered (or, conversely–the more pressure it is cooked under–if one owns and uses a pressure cooker for Indian cooking), the better the flavors will be. Indian sauces thicken by reduction–there is no use of roux or cornstarch to thicken them. Ground onions or nuts add thickness, but primarily, curries are thickened by allowing water to simmer away.

The longer that process takes the better.

Which is why I somtimes will make my sauce ahead of time–up to one whole day ahead and then cook the food in it the next day.

The key turns a half turn here: it takes time for friendships to develop.

When people ask me how I manage to cook big Indian feasts, I smile and say, “I cook large amounts of it the day before and then heat it up the night of the dinner.” When they are incredulous–I point out that every curry I have ever cooked has tasted better the next day, because the spices have all had a long night to mingle and get used to each other.

Another way to build flavors and get your spices to mingle is to make a tarka and pour it into the dish just before serving. A tarka involves the cooking of whole spices–my favorites are cumin and mustard seeds, in heated oil or ghee until they turn toasty brown, smell wonderful and the mustard seeds pop like wee popcorn kernels. (You can also add chiles, onions and garlic to tarkas.) Then the whole sizzling panful is poured over whatever dish is in need of it, just before serving. If you clap a lid on the pot right after pouring in a tarka, then carry the serving pot out to the table, when you unveil your creation, the diners are enwreathed with clouds of fragrant steam.

A dramatic presentation does much to stimulate hunger.

Finally, the sprinkling of garam masala at the end of cooking or just before serving. I think it is best if you make yours fresh, from spices you have toasted. Toasting them is simple: you put them in a heavy-bottomed skillet or pan and shake it over high heat until your spices turn brownish and take on a rich nut-like aroma. At that point, you pour them out into a small bowl, let them cool a bit and then grind them. That is it. It is simple. And if you store your garam masala in a good airtight little jar, it will stay fragrant and good for a couple of weeks–longer, if you leave it in the freezer.

That final sprinkle of toasted spices is like a kiss, a little fillip at the end, a grace note. A final wave before sending your creation out to be appreciated.

That is the final turn of the key, and the lock clicks, and the door swings open.

Of course there are finer points to be learned about Indian cookery. There are other techniques, other methods to use to get the maximum flavor from your spices. But these are the basics–these are all part of the key, which is to know what your spices taste like and learn to combine them together in a way that will make them meld together into a dish that is a perfect balance of flavors, such that no single spice dominates (unless that is the point of the dish) and every ingredient flows together into a seamless whole.

There, friends. I have given you my key–now, go and find the lock and fearlessly open that door.

Culinary wonders and gustatory joy await you on the other side.

Note: Good News!

Thanks to Maureen, who is an avid reader here, and her persistence, I can now tell you that Williams-Sonoma is carrying the Sumeet Multi-Grind in their mail order catalogs. I have seen it so with my own eyes–the new catalog came in today, and lo and behold, there it is on page 16: the exact model that I have. As I have said many times before, it is the best tool for grinding spices and making spice pastes for Indian food, Thai food and Mexican food, ever.

The Sumeet Multi-Grind is only available in the catalog and online; its product number is #75-7595119, and is going for $99.00, which is not a bad price. Zak spent a good deal more to buy mine and have it shipped from India, because I saw it in a magazine and fell in love with it and had to have it. (This was eight years ago, and he has never regretted that purchase. Neither have I.)

Valentine’s Day for Cynics

I really should have posted this last night, but I thought I would show my sweet side on Valentine’s Day.

Now that we have gotten that out of the way, I can give you a taste of the real me: the cynic.

I don’t really like Valentine’s Day, and I never did.

Not only is it one of those holidays that smacks of having been invented by Hallmark Cards as an excuse to sell overpriced bits of pink pasteboard decorated with fluff and glitter, but even when you know the story of St. Valentine, it comes across as bogus.

It is a day fraught with anxiety, sloppy sentiment, and meaningless ritual.

And it has the capacity to transform normally sensible, mature, interesting people into giddy romantics, or worse, disappointed harpies, or anxiety-laden freaks who are sure their romantic overtures are going to be judged as lacking by the object of their affections.

It is hellish if you are alone on Valentine’s Day, when all of the world seems to be awash in red and pink hearts and doe-eyed lovers crowding restaurants eating rich food and swilling Champagne. The sickly-sweet fragrance of countless bouquets delivered wafts around every corner, reminding the less than happy single person that they are still alone.

Bad as that is, sometimes, I think it can be worse if one is part of an established couple during this commercialized feast celebrating “romantic love.”

Because then, if you are together, you are expected to do something to mark the occasion.

Like what?

I mean, when it is a new relationship, and courting behaviors such as surprising each other with flowers or chocolate or bubble baths or little love notes tucked into jacket pockets are all still ongoing, Valentine’s Day is not so bad. It is just an extension of what young, hormone-filled folks are supposed to be up to anyway.

But what happens when you are old and jaded, like me?

(Though, really, I suspect I was born old and jaded, because this attituted about Valentine’s Day goes all the way back to grade school and the passing of valentines to schoolmates was the norm. I always felt bad for the kids who got no valentines because they were unnatractive, poor, bucktoothed, or socially inept for whatever reasons. Watching those kids suffer fuelled my early irritability when it comes to the Pink Holiday.)

I mean, what am I going to do for Valentine’s Day? Go out to a packed, overpriced restaurant where the servers are harried and the wine cannot possibly flow fast enough to numb me enough to keep from getting nauseous from all of the saccharine sentiment floating about? Buy flowers so my cats can turn them into salad and then vomit them up on the couch? (Besides, I prefer my flowers to be living and in gardens–the illustration above is from our old garden back in Pataskala.) Be gifted with a pound of chocolate that I will eat, and then lament eating because I will gain weight?

Where is the romance in any of that?

Half the time, Zak and I forget that Valentine’s Day is coming up, mostly because neither of us cares. We just cruise along in our own little world, unaware that the season approaches. He bought me flowers a few times for Valentine’s Day, and surprised me, because I had forgotten that the Day of Hearts had arrived. Surprises are sweet, but it is hard to surprise either of us with trifles, as neither of us much cares for trifles. (In truth, we both like surprises, but it is hard to surprise anyone on a holiday. Zak is a master of bringing flowers home at odd times, just to pick up my spirits. I am good for finding a cool book or t-shirt and bringing it home to Zak, not for any holiday, but just because he needs a lift. Both of us value these moments more than any pre-planned holiday thing.)

So, I will tell you what I do for Valentine’s Day: I use it as an excuse to cook something I don’t normally cook, and I actually exert myself to cook up to the standards of a fine dining restaurant. While I have culinary training, and I am an excellent cook, I will admit to being a tad too lazy to really haul off, throw down and cook magnificent food that would make a picky gourmand weep all the time.

Besides, if I was motivated to cook like that all the time, it wouldn’t be special anymore. People would expect it, and on top of everything else, we’d all be big as houses.

But the way I see it, once or twice a year, a real culinary throw down isn’t going to kill us all. So, for Valentine’s Day, I put the toque back on, roll up my sleeves and make something fancy.

And this year, I decided to do a pepper-crusted filet mignon, with potatoes a la boulangere and asparagus dressed with browned butter and Meyer lemon juice and zest.

Of course, you all know what we had for dessert.

When Zak asked what he could do for me for Valentine’s Day, my answer was clear:

The laundry.

(And he did it, too. And cleaned the closet. A fine Valentine’s Day present to be sure!)

Anyway, here are the recipes for our supper; the inspiration for the filet came from a method outlined in the March/April Cook’s Illustrated that was meant to create a crispy peppercorn crust that neither fell off nor got overly soggy. I followed their recipe more than I should have–there was too much oil in the crust, and too much salt. I am giving the amounts that I will use the next time I make the dish. Also, they only used plain black peppercorns, while I added coriander seeds and white peppercorns to the mixture.

My potatoes a la boulangere are not traditional in any sense of the word. Based on a French recipe where women would bring simple casseroles of potato, onion, white wine and chicken broth to be baked in the ashes of the baker’s (boulangere’s) hearth oven overnight, I added herbs, spices and Shao Hsing wine to the mixture.

As for the asparagus–it is straightforward. Simmer asparagus in a small amount of water in a saute pan until the desired tenderness is reached. Drain. Melt butter in the pan, with the asparagus, turn the heat to high and allow butter to brown, tossing asparagus in the pan. Squeeze the juice of two Meyer lemons into the pan and add the zest from one, and toss in the browned butter. Add salt and pepper to taste. Serve, sprinkled with some fresh lemon zest.

Barbara’s Version of Pepper-Crusted Filet Mignon

Ingredients:

3 tablespoons black peppercorns, cracked

1 tablespoon white peppercorns, cracked

1 tablespoon coriander seed, cracked

4 tablespoons plus two teaspoons olive oil

1/2 tablespoon salt (to your taste)

4 center-cut filets mignons, 2″ thick, around 8 ounces each, trimmed of silverskin (I left the tiny bits of fat on my steaks because they came from Belgian Blue cattle, which are very, very lean animals. The tiny amount of fat present helped keep the meat moist as it cooked.)

Method:

Heat the 4-5 tablespoons olive oil over medium heat. Add the spices, and stirring occaisionally, simmer until the spices and oil are quite fragrant–between five and eight minutes. Remove from heat, and set aside to cool. When it is at room temperature, add salt and stir well to combine.

Rub steaks with the spice and oil mixture, coating all sides, but paying particular attention to the top and bottom surfaces. Press the peppercorns in with your hands, then set steaks on a plate, cover with plastic wrap and press firmly again in order to set the spices into the meat. Allow to sit at room temperature for about an hour.

Heat 2 teaspoons of oil in a 12 inch cast iron skillet until it is barely smoking. Sear the steaks on one side without touching or moving them for 3-4 minutes in order to let a heavy crust form. Turn the steaks with tongs, and do the sear the other side in the same way. (Here is a tip–if you go to turn your steaks and they stick–they are not done searing. Leave them in place, wait 30-60 seconds and try to turn them again–repeat until they turn easily.)

When the crust is formed on the bottom–check to see if the steaks are sticking–if they are not, the crust is formed–cover loosely with a lid–I used the domed lid to a pan that was larger than the skillet so I could set it askew to let the steam out. Cook for another 3 minutes for rare, 5-6 minutes for medium rare. (If you want them more done than medium rare–cook something other than a filet, please–something with lots of fat, like a ribeye, that will stay moist under extended cooking conditions.)

Remove from pan, set on warmed plates and allow to rest for five minutes before serving with a pat of compound butter, if you wish.

Potatoes a la Boulangere in Individual Gratins

Ingredients:

3/4 pound fingerling potatoes, well scrubbed

1 tablespoon olive oil

4 small or 2 large shallots, peeled and sliced thinly

1 tablespoon fresh rosemary, minced

salt and pepper to taste

1/4 teaspoon spicy curry powder

4 pinches smoked paprika

1/2 cup chicken or vegetable broth

1/4 cup Shao Hsing wine or dry sherry

1 teaspoon butter

Method:

Preheat oven to 325 degrees.

Using some olive oil or butter, grease four small shallow gratin dishes well.

Boil potatoes in their skins until mostly done, but still pretty firm in the center. Drain and cool.

Heat olive oil up in a small saute pan, and cook shallots until they are medium golden in color. Add rosemary and cook for a minute or two more until the herbal fragrance is released.

Slice potatoes into 1/4″-1/8″ slices. Layer a set of slices on the bottom of the gratins, then sprinkle with salt and pepper, some of the curry and paprika, and scatter a bit of the shallots over the potatoes. Salt and pepper the potatoes to taste. Do a second layer, the same as the first, finishing with shallots, then pour 1/8 cup of broth and 1/16th cup of wine into each gratin. Dot them with butter.

Put the gratin on baking sheets, and pop into the oven. Allow to bake, uncovered, until most of the broth is absorbed, and the bottom layer of potatoes is tender and velvety, while the top layer is browned and crisp. Add some extra broth if needed. Garnish with a sprig of fresh rosemary.

A Cake Fit For An Emperor: Gateau de Mumtaz Mahal

Roses are the queen of flowers. They are sensual with their profusion of velvety petals from which waft their seductive scent.

Although the use of roses in cookery has fallen out of favor in the West, they were once quite popular, particularly in the Medievaland Rennaisance periods. Rosewater and attar of roses were used not only in perfumery, but also in cookery and baking. Although it seems quite odd to think of it, roses were not even relegated to the art of pastry–they were also used to sauce meats, or flavor meat and rice-based dishes.

But fashions change, and Europeans have, by and large, forgotten their attachment to the rose as a flavoring and even in baking have moved on to favor vanilla, chocolate and fruit as their flavorings of choice.

In other parts of the world, this is not so. The Persians were and are great lovers of the rose, and still use it in flavoring both sweets and savories. Lebanese bakers use rosewater to flavor baklava, and the Turks are known to eat gorgeous crimson jellies made from rose petals.

However, the Indian subcontinent is where I turn when I think of roses.

I don’t know quite why, as I was first exposed to rosewater in food via Syrian and Greek cookery. But, when I smell rosewater in a cake or cookie, the first place my palate is transported to is India: northern India, to be exact.

Which is a good thing, because Meena of Hooked on Heat has challenged us to use our imaginations to come up with a dish made for love for her third edition of “From My Rasoi.”

Nothing says seduction and love to me like roses.

Knowing as I do, the penchant for northern Indians to use rose (gul) as a flavoring in sweets, it got my mind working. I decided upon a cake, baked in my rose-shaped pan, that combines the very northern Indian flavors of rose, almond, and cardamom, combined to create a fusion dessert worthy of the palate of a Mogul Emperor.

When I found a jar of Pakistani “rose petal spread” at Patna’s on Sunday, I snatched it up, unsure of what I was going to do with it, but knowing that it would be involved in this Mogul cake in some way, shape or form. Ashwini kindly told me that the honey and sugar-preserved rose petals are called “gulkand,” and that she uses it to make phirni. (Zak has not heard of this yet–phirni is another name for his favorite dessert in all the world, something he likes even better than barfi–kheer. Cardamom scented rice pudding. I can only imagine what he would do with rose-scented kheer….)

I thought about it and thought about it. I opened the jar when we got home and the scent of red roses engulfed me, and I remembered my beloved rose bush (Bell’Aroma is the variety–we named her Aradia) we had planted in our dooryard in our old house in Pataskala. That bush could fill the entire garden with scent with one bloom. As soon as you walked out the door, her fragrance would embrace you like a cloud of olfactory joy.

I tasted the gulkand, and it had the texture of a very tight, somewhat grainy preserve. I immediately thought of a use for it–mixed with chopped almonds, I could use it as a filling for the cake.

I also determined that if I thinned it with more honey, and heated it up in the microwave until it became liquid, I could brush it over the cooled cake in order to add flavor and moisture–a trick I learned in my baking and pastry classes in culinary school. This step also helps seal the cake to keep crumbs from being picked up by the icing or frosting, when doing layer cakes. (Although, since I was using my rose-shaped Bundt pan for this, I wasn’t going to be spreading frosting, but drizzling glaze, so the crumbs would not be an issue.)

I adapted a recipe from the cookbook, Bundt Classics, which my mother had bought for me to go with the ever-expanding collection of interestingly shaped Bundt pans she keeps adding to year after year. The original recipe is for Strawberry White Chocolate Cake, but I changed the flavorings from vanilla and almond to almond, cardamom and rose, added the filling, and the gulkand glaze, and then drizzled a thin rosewater and cardamom icing that I tinted pale pink with Wilton burgundy paste color. (It makes a prettier pink than the scarlet color does.)

It turned out fantastic.

All that was left was to come up with a name.

Since the Taj Mahal is my favorite building in all the world, I decided to name the cake for Mumtaz Mahal, the wife of the Mogul Emperor Shajahani. She must have been a rose among women to inspire her husband to build such a beautiful memorial, so I feel it is proper to name a rose among cakes in her honor.

Gateau de Mumtaz Mahal

Ingredients:

1/2 cup finely chopped almonds

1/2 cup gulkand

4 ounces white chocolate, chopped (I used Lindt)

1 cup milk

1 1/2 cups sugar

1/3 cup butter, softened

3 ounces cream cheese, softened

2 eggs

1 teaspoon almond extract

1 teaspoon rose extract (I used Star Kay White Brand–you can get it at Sur la Table or at baker’s supply stores)

2 3/4 all purpose flour

1 tablespoon baking powder

1 teaspoon freshly ground cardamom seeds

3/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 cup gulkand

2 tablespoons honey

1 cup powdered sugar

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground cardamom seeds

3 tablespoons rosewater (I use Cortas brand from Lebanon)

milk or cream as needed

food coloring

Method:

Preheat oven to 350 degrees F.

Mix together chopped almonds and gulkand and set aside. (The easiest way to do this is by lightly oiling your hands and mixing it together with your fingers. It is sticky, so look out!

Grease and flour a ten cup Bundt pan or tube-shaped cake pan and set aside.

Put chocolate and milk into a saucepan and over medium heat, melt chocolate, whisking it into the milk until just combined. Remove from heat and allow to cool.

Using a mixer, cream together sugar and butter until light and fluffy. Scrape down sides of bowl as needed. Add cream cheese and beat until fluffy again, scraping down the bowl as needed.

Add eggs and extracts, and beat until well combined. Add cooled milk and chocolate, and beat until well combined.

In a separate bowl, mix together flour, baking powder, cardamom and salt. Add to liquid ingredients, and beat, scraping down the bowl as needed until a thick batter is formed.

Spoon 2/3 of batter into prepared pan. Tap pan on the counter lightly to get batter down into all the nooks and crannies of the pan.

Pick up tablespoonsful of the gulkand/almond filling, and shape it into segments of a ring. Set these down into the batter, overlapping so you make a circle around, but not touching the central hole of the pan. Spoon the rest of the batter over the filling.

Place into oven, and bake for about 50-60 minutes, or until toothpick insterted in center of cake comes out clean. Cool in pan for ten minutes. Remove from pan by putting rack over top of cake and inverting cake, rack and pan together and then gently shaking and tapping pan. (Baker’s Joy spray is the best stuff to use to grease and flour pan to get it to release.)

Allow to cool until only barely warm.

Melt gulkand and honey together in microwave until mostly liquid. Brush all over cake with a pastry brush. Allow to set for about five to ten minutes.

Whisk together remaining ingredients into a thin glaze. (Use only as much milk or cream to make a thin glaze.) Tint it pale pink, and drizzle over cake. (To do this with as little mess as possible, I place cake on a big cooling rack over the sink, and then drizzle away. The excess glaze goes down the sink where it is easily rinsed away. Just make sure you have a big enough rack to do this–if not, you risk your cake falling in the sink, and that is definately a tragic thing. to have happen.)

Serve with strong coffee.

Note: If you cannot find rose extract for the cake, use vanilla–the rose extract in the cake is barely discernable, and the gulkand filling, glaze and rosewater icing give plenty of flavor to the cake.

In Memory of Edna Lewis, Southern Cookbook Author and Wonderful Human Being

I looked at the New York Times today and found out that not only has Hackett dropped out of the Senate race here in Ohio (I was planning on working for his campaign) , but Edna Lewis has died.

It is truly a bummer of a Valentine’s Day for me.

I wrote an announcement over at The Paper Palate about Miss Lewis’ death, but I thought I would give a few more personal thoughts here.

Miss Lewis was always her own person, who always went her own way. Born in Freetown, the granddaughter of a former slave, she grew up planting, harvesting and cooking fresh foods with the seasons in her rural community, and she learned early on what a difference truly fresh foods made in flavor.

In that sense, the very first time I picked up her first book, The Taste of Country Cooking, I immediately felt a deep and abiding kinship with this woman who was decades my elder, but whose early culinary experiences mirrored my own. She knew the experience of shelling fresh peas on the porch with her family, the taste of a piecrust made with home-rendered lard, and the incomparable sweetness of corn picked, shucked the dropped briefly in boiling water. She conveyed these memories in a way that could make those who had never done these things understand the importance of them, and from her, a generation of can-opener cooks first began to learn to make Southern food that was not a woeful concatenation of processed foodstuffs.

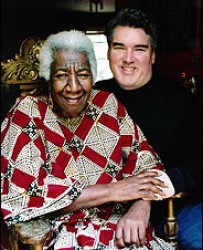

In her later years, she parnered with the young talented and openly gay chef, Scott Peacock, to write a book called The Gift of Southern Cooking, which was published in 2003 to great critical acclaim. Critics, cooks and food industry professionals all lauded the partnership between the two authors, a partnership that became a deep friendship, but Miss Lewis’ family felt differently.

As her health failed, Scott became her caretaker, a role that the two of them made legal as the years went by. The lived together, and Scott, even though he was running a very successful restaurant, took very good care of her.

Miss Lewis’ family launched a legal fight to try and force Miss Lewis, whom they said was not competent to make decisions regarding her care, to be given to their custody. Miss Lewis and Scott successfully fought them off, but, one wonders, at what cost to Miss Lewis’ peace of mind?

In addition to always thinking of Miss Lewis when I eat Southern food, I think I will always remember her as someone who embodied my belief that love is what we make of it, and there is nothing more sacred in the world than love between people. Kinship is not soley defined by genetics: it is defined by whom we choose to love.

Miss Lewis and Scott, who have received great support from the culinary community, were known fondly as “The Odd Couple of Southern Cooking,” because of their differences in age, race, and sexual orientation.

I think that their relationship embodied that which is most sacred about Southern cooking and food: love and sharing. They loved each other, and were happy together, and they forged familial bonds that transcended time, skin color and sexuality. They were kin in the truest sense of the word, and because of that, I think that every time I bite into a biscuit or tear into an ear of corn or fry chicken, I will think not only of Edna Lewis, but of her friend, Scott Peacock and their love for each other and the Southern food that they both worked to preserve and promote.

Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

Book Review: Monsoon Diary

Some prose is like poetry in its rhythym; words pattering like raindrops against a rooftop, liquid syllables dripping honey on the tongue and in the heart. Images arise from phrases, teasing the reader with haunting reminiscences so visceral that they might as well be their own. A gifted writer can deftly unfold sentences and engulf the senses with flavors long past, hurtling the reader headlong into a yearning for a place she has never known.

Such is the beauty of Shoba Narayan’s prose in Monsoon Diary: A Memoir With Recipes.

Of course, it isn’t all pretty words and poetry; Narayan is a skilled storyteller as well. She narrates her life, from childhood to early adulthood, with gentle wit, passion and not a little humor. A trained artist, she paints portraits of her immediate and extended family in words so vivid that one can easily see the antics of her grandmother, Nalla-Ma, in whose home she lived for her first four years of life.

Nalla-Ma was a proud, fierce woman who cooked passionately and beautifully, but ran her kitchen and her household like a field marshall. She bullied the vegetable sellers, fussed at her servant, and was the terror of the neighborhood, but she doted on her grandchildren and loved them with all of the strength her body, heart and mind possessed.

Narayan recounts Nalla-Ma in the kitchen, making vatral in the heat of summer, just before monsoon season. Vatral are sundried preserved vegetables that are kept for the cooler months when fresh vegetables are not as available and are more expensive. The entire process was lengthy, and required much cooperation between Nalla-Ma and her servant, Maari, a woman with whom Nalla-Ma was always irritated. Somehow, every summer, the vatral would get done, though there were many quarrels and difficulties to be overcome.

Of course, food is the major thematic component that is woven throughout the narrative of Monsoon Diary. Narayan notes that her family, like many in South India, were obsessed with food, and through every rememberance, it is made very clear that the fabric of her entire community was made up of food that changed with the seasons, marked life transitions, celebrated holidays and held every individual together as one people. In sharing food, whether it was with schoolgirls on the playground at lunchtime, or with the Gods at the temples, the community was made stronger, binding individuals together almost as close as family. (When, years later, Narayan jumped into a cab driven by a fellow native of Chennai, she found herself and her friend taken to his home for lunch with his wife, and then dropped off at their intended deestination, without charge. The cabdriver said, “You are from my town. You are like a sister to me. Does one take money from a sister?”

Travel and transportation are major motifs in the book, and Narayan unsurprisingly tells of how she could guess where fellow passengers on the train in India were from by what was in their tiffin boxes. She and her brother liked to strategically seat themselves next to Marwari women from Rajasthan, for they were known not only to be wonderful cooks, but were generous when they shared their food. Of course, they shared their mother’s own delightful idlis with coconut chutney with their new friends, once again, creating community, even if it is a temporary one, among the passengers of a train.

It is the sacred nature of food, and its role in tying people together into communal groups that struck me as I read the book. Yes, Narayan describes the food in beautifully, such that I was about to drool on the pages as I voraciously devoured the words. But, more than the descriptions of the delicious foods and the recipes that end each chapter, I was drawn to the way she shows food as not only a carrier of culture from one person to the next, but a sustainer of culture. Not only did it transmit culture and tradition by being passed down from mother to daughter, but it also spread that culture from family to family, across India. The openness, warmth and humor that comes from sharing food together is a potent force in human existence, and Narayan captures that essence in her memoir.

And it is that message which will stay with me long after I have forgotten how it was she described Nalla-Ma’s rasam as tasting.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.