Bitty-Wee Courgette

I grew up calling them squash.

But, doesn’t courgette sound just the tiniest bit better than–squash?

“Squash” sounds icky.

“Courgette” sounds classy.

By whatever name you call these summer beauties, they are members of the cucurbit family–a wide ranging group of fruiting plants which includes courgette, gourds, pumpkins, melons and cucumbers.

The unfortunate name, “squash” comes from the Native American term, “askutasquash,” which means, “eaten raw.” Which is true, when it comes to cucumbers, some summer squashes, and melons–heck, most of the cucurbits are good when eaten raw. Pumpkins, winter squash and gourds–well, I am not so certain that the Native Americans were talking about them when they were discussing the idea of eating the vegetables raw.

The tiny gem-like lovelies I have pictured here not only are courgette, or summer squashes, they are babies. Yes, babies. Very small–the longest zucchini pictured is about the length of my middle finger, and about as big around. I discovered this year that courgette, when picked very small and immature, almost just as the fruits first start to form, are velvety-sweet, with smooth firm flesh uninterrupted by seeds.

It is very often the seeds that seem to squick the people who tell me they don’t like squash or cucumbers or whatever it is. The seeds don’t much bother me, but I will say that the firm flesh of these little ones was very tender, sweet and flavorful, and it was nice to have the uniform texture throughout, especially since I used them in a quick saute. Larger specimens, when treated this way will often become quite squishy and start to fall apart, because of the presence of the seeds.

It is very often the seeds that seem to squick the people who tell me they don’t like squash or cucumbers or whatever it is. The seeds don’t much bother me, but I will say that the firm flesh of these little ones was very tender, sweet and flavorful, and it was nice to have the uniform texture throughout, especially since I used them in a quick saute. Larger specimens, when treated this way will often become quite squishy and start to fall apart, because of the presence of the seeds.

Not so the baby ones, as you can see at right.

They turned out to make a delicious quick vegetarian supper when I paired them with cherry tomatoes, cooking the lot until the courgette turned a nice golden brown and the tomatoes wilted slightly and released a bit of juice. At that point, I tossed them with some penne pasta, and stirred in some pesto I had in the freezer.

Pesto is great stuff to have lying about when one is famished and wants a quick meal. When I make it, I always make way more than I need–it is such a powerful sauce that you only use a tiny bit to dress pasta, or to add flavor to chicken or a soup. But I make much more than necessary so that I can put the leftovers in a freezer bag or two, push out the air, and throw it in the freezer. Since I make pesto at least once a week in the summer and fall, this means that over the winter, I usually have enough pesto frozen to give Zak and I a taste of summer bliss when the wind is howling and the snow is falling outside.

Pesto is great stuff to have lying about when one is famished and wants a quick meal. When I make it, I always make way more than I need–it is such a powerful sauce that you only use a tiny bit to dress pasta, or to add flavor to chicken or a soup. But I make much more than necessary so that I can put the leftovers in a freezer bag or two, push out the air, and throw it in the freezer. Since I make pesto at least once a week in the summer and fall, this means that over the winter, I usually have enough pesto frozen to give Zak and I a taste of summer bliss when the wind is howling and the snow is falling outside.

Last night, I made a slightly more elaborate version of this pasta dinner. I used some baby eggplants in addition to the courgettes, and added onions and red peppers to the mixture. In another pan, I also sauteed up some chicken, broccolini, mushrooms and onions, and then made up a gigantic batch of pesto and a huge pot of penne.

We had six folks for dinner, and this way, everyone could customize their plates. Those who wanted vegetables only could have them. Those who wanted the chicken mixture could have it, and those of us who love all vegetables and fowl, could have both, with pesto for all.

It turned out to be a colorful, fragrant and flavorful dinner.

But, alas, of course, I forgot to take pictures, so you will have to take my word for it that it was good.

I don’t know if I will always remember to call squash courgette–but I hope so. I think they just sound more appealing when I call them that, and it might mean that I could entice more people to appreciate them.

Which is good for me, because it means I will be able to think of more ways in which to use the bitty-wee beauties.

And Yet Another Episode of Weekend Cat Blogging

You know, the reason we don’t make our bed isn’t just because we are lousy housekeepers.

You know, the reason we don’t make our bed isn’t just because we are lousy housekeepers.

It is because we have a day shift who makes use of it after we have gotten up.

At any given time of the day, there are at least two cats in residence upon our bed.

Ozymandias, King of Cats (he is the large grey one in the picture there) holds court in our bed from mid-morning on. At his side is usually Tristan, who is his major-domo, valet, fartcatcher and general boy Friday. Trizzy–the Siamese–will sometimes leave Ozy in the capable hands of Springheel Jack, who is the larger of the two tiger cats.

And then, there is Gummitch. Gummitch loves to cuddle. Jack is his usual cuddle buddy, as you can see here, and in a formerly posted photograph.

But, lacking Jack, he will make due with any old thing such as our plum-colored blanket.

No creature in the world can enjoy sleep so completely and voluptuously as a cat.

And few creatures are as disgustingly adorable in their sleep as a feline.

I mean, really. Look at Gummitch. Not a care in the world.

And look how he twists himself into a yogic stretch while yawning.

I hope that in my next life, I reincarnate as a beloved housecat.

For more weekend cat-blogging, visit Masak-Masak and see Ally with some stuffed animal friends. At Farmgirl Fare, check out Gretel, who is eighteen years young, sitting in the sun. And at Eatstuff, Clare shows us how tiny Kiri was when he was a baby. Last, but certainly not least, we have Tanuki showing off color coordinated stripes and eyes at A Cat in the Kitchen.

So, if you are a blogger, and you have cats and want to show the foodies of the world that there is more to life than eating, then join us. Just post pictures of your cat this or any Saturday, and send the link to Clare at Eatstuff, and we’ll share links to your catfriends on our blogs.

Crispy-Chewy-Oniony Goodness: Scallion Pancakes

Mmmm. Scallion pancakes.

Such is the power of the pancake, that last night when Zak and Dan were sitting around the kitchen, keeping me company, and I was rolling the dough out into flat rounds, Zak looked up and said, “What are you doing?”

“Making scallion pancakes.”

His eyes lit up and he smiled. “Oooh. Scallion pancakes. I didn’t know you were making scallion pancakes.” He paused and looked lustily up at the dough as I sprinkled chopped scallion and cilantro over it before rolling it up like a cigar. “I love you,” he said.

Dan settled his shoulders and said, “I knew she was making scallion pancakes. She told me in email.”

Sometimes, the husband is the last to know what is for dinner, but he accepts this with good grace and eats every last bite of whatever it is that is put before him.

Like the scallion pancakes.

Now that I have said “scallion pancakes” about a million times in the past couple of paragraphs, let’s talk about what the heck they are.

They are a pan fried bread of Chinese origin, that are constructed very similarly to the Indian parathas, and they are eaten typically as a snack in China. I am told on good authority that they are often sold by street vendors in Beijing, in some of the night marketplaces–essentially urban markets set up after the sun goes down where vendors sell snacks and quick homey meals. I have been told by none other than Grace Young, author of Breath of a Wok and The Wisdom of the Chinese Kitchen, that these markets are an endangered species in China; public health officials seem bent upon closing them down.

Hopefully, scallion pancakes, or green onion cakes as they are sometimes called, will remain.

I do not know the origin of these delightful rounds of crispy on the outside, chewy on the inside fried dough. I have read that they are a speciality of Beijing, which makes sense; wheat, not rice, is the staple grain of the cold northern provinces and many wheat flour specialties call the capital city home. Bao, or steamed buns, are said to have come from Beijing, and boiled wheat dumplings and potstickers, can also be traced to the Imperial City.

But, on the other hand, I have also heard that Shanghai is where scallion pancakes originated.

Unfortunately, this also makes sense; Shanghai also is the birthplace of many wheat flour creations by virtue of it having been a city where many “farang”–foreigners–lived while they conducted trade business, missionary activities and attempted to create of China a full-scale European colony. (Which, with the exceptions of Hong Kong, Kowloon and Macau, was a failure–thankfully.) French, British, and Portuguese people lived in Shanghai, and because of this European influence, a lot of baked pastries and breads came about as specialties of the city. These pastries and breads had the look of European baked goods, but because of using bean paste, sesame seeds and lotus seed paste, retained a distinctly Chinese flavor.

In addition to the Europeans, Shanghai had a significant Indian population who had come along with the British.

I mention this because of the fact that the way in which scallion pancakes are put together is so very reminiscent of the Indian filled and fried flatbreads called paratha. It is possible that paratha were the inspiration for this soul-satisfying Chinese snack, and the origins are now lost in the mists of time and legend.

In the end, it doesn’t really matter where green onion cakes came from, what matters is where you can get them now.

In the end, it doesn’t really matter where green onion cakes came from, what matters is where you can get them now.

And if you live in the US, there aren’t too many places to get them, which is why I bothered to learn how to make them.

I first ate them in Athens, at our favorite Chinese restaurant, China Fortune. Neither Zak nor I had seen them on a menu before, but we were urged to get them by friends, and they came out crispy and golden, cut into petal shaped wedges, with a soy and ginger based dipping sauce. After one bite, we were hooked, and for years, we would go out for Chinese food just to get scallion pancakes.

But then, we moved away. And though we went to a bigger city (Providence, Rhode Island), it took us a long time to find any evidence of any scallion pancakes anywhere on any menu. One restaurant had them–and they made a variation of them that was delectable–they made the scallion pancakes as usual, then used a cooked minced pork and dried shrimp filling, which they sprinkled on one pancake, and then topped with another, rolling them together to seal the edges of the dough.

But then, we moved away. And though we went to a bigger city (Providence, Rhode Island), it took us a long time to find any evidence of any scallion pancakes anywhere on any menu. One restaurant had them–and they made a variation of them that was delectable–they made the scallion pancakes as usual, then used a cooked minced pork and dried shrimp filling, which they sprinkled on one pancake, and then topped with another, rolling them together to seal the edges of the dough.

Then, they were pan-fried to crunchy, chewy perfection and served with a spicy soy dipping sauce.

And then, my friends, this restaurant went out of business. They hooked us on the filled pancakes and then left us high and dry.

We found one other restaurant that offered them.

But what they served bore no relation to a real scallion cake. They served two flour tortillas filled with slivered scallion tops glued together with water and fried to a dry, crumbly texture. It was like eating fried cardstock–flavorless and messy. I remember trying to choke them down, and wanting to cry. I looked up at Zak and I could tell he felt the same.

There was nothing for it.

I had to learn how to make them.

I discovered, as I read cookbooks and experimented with the dough, that the pancakes really aren’t hard, just involved. You cannot rush making them, but you can make them ahead of time and wrap them carefully and either refrigerate and freeze them. Then, you can take them out, thaw them and fry them at the last minute, and look like a big genius when you serve them to your guests.

I discovered, as I read cookbooks and experimented with the dough, that the pancakes really aren’t hard, just involved. You cannot rush making them, but you can make them ahead of time and wrap them carefully and either refrigerate and freeze them. Then, you can take them out, thaw them and fry them at the last minute, and look like a big genius when you serve them to your guests.

Though you can do that, I still like to make them fresh. The crust cooks up more crispy that way.

They are also best served right away, before the crust begins to steam and become softer. The best thing to do is to serve them right after they have come from the oil and cooled slightly on paper towels. Cut them into wedges and send them out on a plate to your guests who will be standing around like vultures in the kitchen, waiting to dive upon each golden morsel of goodness that you pass around.

When I serve it that way, I always make sure that the last cake or two are saved for the cook and the cook’s assistant, because those who stand over the hot oil need to be looked after. Once you start serving these addictive packets of flavor, you cannot trust your friends to look after the cooks. They will eat so long as you put scallion pancakes before them.

And who can blame them, really.

And who can blame them, really.

They really are that good.

You can serve them as an appetizer, as part of a dim sum party menu, or with soup as a main meal. Florence Lin suggests egg drop soup, but I like them with hot and sour soup, personally, but that may be because I prefer hot and sour soup.

Last night, I went ahead and served them with the entree–a pork dish that I made with some special Guilin chile sauce and fermented black beans. I held the pancakes in a heated oven–they did soften up a bit, but not so much that they stopped Zak, Dan and I from gobbling them up along with our rice and pork and vegetables.

I made certain to have Dan and Morganna take a lot of photographs of the making of the cakes because I have found that verbal description without physical demonstration leads to confused people when it comes to making scallion pancakes. They look harder than they are, really–once you have made a couple of them, they become simple, and you can make them quite quickly and easily.

I made certain to have Dan and Morganna take a lot of photographs of the making of the cakes because I have found that verbal description without physical demonstration leads to confused people when it comes to making scallion pancakes. They look harder than they are, really–once you have made a couple of them, they become simple, and you can make them quite quickly and easily.

My mother is a great fan of them; the only experience in Chinese food she has had was the dim sum party at a great Chinese restaurant in Providence we had when I graduated from Johnson & Wales, and the foods I have cooked for her. From the first taste, she took to scallion pancakes like a duck to water, and she loves to watch me make them. If you make enough of them, your hands know the tricks of it and move along seemingly without direction from you, while you chatter along and keep up a good lengthy gossip about the cousins, aunts and uncles, while a stack of rolled out, filled cakes grows higher and higher.

Another note before I give you the recipe–follow the pictures, and remember that the ratio of flour to water is 3:1. That way, if you only want to make a few pancakes, you can reduce the flour to one cup and use one third cup water, and all will be well. The procedure of mixing and shaping is exactly the same.

Ingredients:

3 cups flour

1 cup hot water

1/2 bunch scallion tops, sliced thinly

2 teaspoons sesame oil

salt and ground pepper mixed together

peanut oil for frying

Other stuff you will need:

canola oil spray

waxed paper

Method:

Put flour in a medium sized mixing bowl, and add water all at once. The traditional way is to stir it all in the same direction with one or two chopsticks, but you can use a silicone spatula or a bamboo or wooden spoon. Use whatever is comfortable for you.

Mix until most of the flour is mixed in, though the dough will seem quite dry.

At this point, lightly flour or oil your hands and turn dough out onto a silpat or a lightly floured surface and knead for about ten minutes until a very nice, smooth dough is formed. Wash out your bowl, dry it carefully, and put the dough ball back into the bowl and cover it tightly and allow it to rest for at least thirty minutes.

Put your sesame oil in a small bowl, and your salt and pepper together in another small bowl and your scallions in a third small bowl and set them in a row, left to right: oil, salt/pepper, scallions.

When your dough has finished resting, take it out and roll out into a long snake shape, about one inch or so thick. Cut the snake in half, then cut into 1 1/2 inch pieces–I like to use a bench knife for this, but a knife or a cleaver work fine, too.

Roll each lump of dough into a round and flatten slightly. Put all of them back into the bowl and cover, except for the one you work with.

Take your flattened disk of dough and using a rolling pin, roll it into a circle, about 1/8 of an inch thick. (I like to use a rolling pin without handles–it is more nimble for this purpose.)

Take your flattened disk of dough and using a rolling pin, roll it into a circle, about 1/8 of an inch thick. (I like to use a rolling pin without handles–it is more nimble for this purpose.)

Dip two fingers into the sesame oil, smear the surface of your rolled out dough with it. Sprinkle a pinch of salt and pepper over the surface of it, and then take up a scan’t 1/2 teaspoon of scallion slices and scatter over it.

Then, lift up the edge of the dough circle closest to you and roll it up like a cigar. Pinch the seam down the long side closed, and pinch the ends closed.

Then, take the rolled up dough, and make a snail-shaped disk out of it by coiling it on itself. Pinch the seams closed, then flatten it with the heel of your hand into a disk.

Then, take up the rolling pin and roll it into a flat pancake.

Spray a piece of waxed paper with the canola oil spray and set the pancake down on it. Spray the top of the pancake and lay another piece of waxed paper over it.

Repeat until all of your lumps of dough are used up.

At this point, you can wrap your stack of pancakes tightly in plastic wrap then put it in a freezer bag and freeze it.

Or, you can cook them.

Heat the peanut oil in a shallow frying pan until it bubbles when you put a bamboo chopstick’s tip in it. Slide in as many pancakes as the pan will hold and fry about a minute or so, or until golden brown on the bottom, then flip it over and cook until done on the other side–about forty-five seconds or so. When done, drain on paper towels.

Heat the peanut oil in a shallow frying pan until it bubbles when you put a bamboo chopstick’s tip in it. Slide in as many pancakes as the pan will hold and fry about a minute or so, or until golden brown on the bottom, then flip it over and cook until done on the other side–about forty-five seconds or so. When done, drain on paper towels.

Repeat as necessary.

Serve hot.

Note:

You can add minced cilantro and/or garlic chives to the scallions in the pancakes.

Dipping Sauce:

Ingredients:

Light soy sauce

rice vinegar

sugar

Optional add ins:

sesame oil

minced garlic

minced ginger

minced cilantro

white pepper

chile garlic paste

ground sichuan peppercorn

This is all to taste–you mix together roughly equal parts soy sauce, vinegar and sugar, until you have a tangy-sweet-salty flavor that you like. (Some people also use some chicken broth in this recipe–I do sometimes, but more often I do it that way for steamed dumplings. For the pancakes, I like a stronger flavor.)

Then, you mix in some or all of the optional ingredients to taste. Sesame oil is used in small amounts–like a few drops–because it is very strongly flavored. Everything else is up to you.

You can make several different sauces–that way the folks who like chile fire are happy and the folks who like ginger tang are saved from having their tongues burned off in a chile inferno.

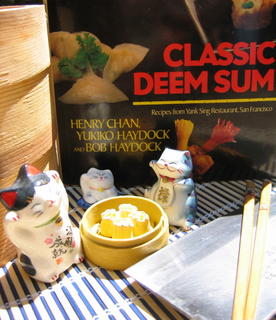

The Chinese Cookbook Project V: America’s Dim Sum Pioneer

Henry Chan is a man with a vision.

Henry Chan is a man with a vision.

He envisioned a dim sum restaurant in the United States with impeccable service, a refined atmosphere and clean bathrooms.

And eventually, after a great deal of family drama between he and his father, he managed to turn Yank Sing, the restaurant his beloved mother, Alice Chan, started in 1958, into the restaurant he had seen in his dreams. Now, forty-seven years later, Yank Sing is known throughout the United States and the world as -the- place to go for dim sum in San Francisco, a city teeming with dim sum palaces and teahouse dives.

“Dim sum”, for those who are not familiar with the term, literally means, “touches the heart,” or “dot the heart.” It refers to a variety of small snacks which are eaten with tea in special restaurants called teahouses. The practice of going out for dim sum is known as “yum cha,” which means, “to drink tea,” and it is a weekend tradition in Hong Kong and the southern province of Guangdong in China. The tradition of teahouses spread wherever Cantonese people who left China settled, and it is said to have first appeared in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the 1940’s or 1950’s. Certainly at the time that Alice Chan and her son Henry, arrived in the early 1950’s with the rest of their family, she got a job at Lotus Garden, one of the two existing dim sum restaurants in San Francisco.

The secret to Yank Sing’s success is not only that Henry Chan held it to a higher standard than all the other dim sum restaurants in San Francisco, insisting that the service and dining room be as elegant as any fine dining establishment that American foodies love. The heart of Yank Sing lies in the beautifully prepared dim sum specialties from a menu which includes a staggering one hundred varieties. Though “only” about sixty varieties of dim sum are available on any given day, each type is created lovingly by hand and with exquisite care in huge kitchens where highly skilled workers wrap up to 360 potstickers an hour.

That is a lot of potstickers.

Dim sum is best experienced in a restaurant or teahouse setting, but I have been teaching home cooks how to make it for about seven years now, and my dim sum classes have been constently the most popular ones I have offered. I have been experimenting with home recipes for dim sum for longer than that, developing my own ways of making various teahouse favorites.

As an outsider to Chinese cookery, I am put at a unique vantage point when it comes to evaluating dim sum recipes–most Chinese or Chinese Americans have a plethora of kitchen tricks that they grew up with, shortcuts that have been passed down in their families for generations. Non-Chinese Americans such as myself did not grow up with hese kitchen traditions, so in a lot of ways, we are more able to see clearly whether or not a recipe is written in a truly user friendly way, and if the instructions will help the home cook create not only an edible result, but a flavorful one, too.

The recipes in Classic Deem Sum: Recipes from Yank Sing Restaurant, San Francisco, by Henry Chan, Yukiko Haydock and Bob Haydock (Holt, Rhinehart and Winston, New York, 1985) represent some of the clearest and most “authentic” dim sum recipes I have had the pleasure to work with and peruse.

When I say they are clear–they are written quite simply, with step-by-step instructions, in a format which is easily followed by novices and old hands at Chinese cookery. I attribute that to the work of Henry Chan’s co-authors, the Haydocks, who had previously produced three other cookbooks on Japanese cooking for American audiences.

Interestingly, this is the first book I have ever seen which advocates the use of a tortilla press in rolling out har gow or potsticker wrappers, a practice I had not heard of until it was suggested to me by someone out there in the blogosphere. Every other Chinese person I knew of who made wrappers from scratch for their own dim sum specialties (when they made them at all), rolled them out using a small rolling pin. However, not long after first hearing about the tortilla press, I went out to eat at Shangri la in Columbus, and lo and behold, the owner was sitting in a corner of the dining room, pressing har gow wrappers with a tortilla press and then wrapping them with nimble pinches of her fingers.

Since the dim sum at Shangri la is the best I have ever had in Ohio that I didn’t have diddly-squat to do with making, I couldn’t help but figure that the practice of using tortilla presses as a time-saving device in dim sum restaurants was not only widespread, but didn’t seem to hurt the flavor or texture of the dumplings in any appreciable fashion.

So, there you are, folks–cross-cultural grassroots cooking advice, brought to you by a friendly blogger with a penchant for out of print cookbooks. What more can you want from life?

The reason I use the loaded term “authentic” to describe the recipes (even though it is hardly “authentic” to use a tortilla press in a Chinese kitchen) is simple: the authors call for lard, pork fat and pork to be included in nearly every dish, a sure sign that a traditionalist is at the helm in the dim sum kitchen. Pork fat is the reason why so many dim sum specialties taste so blasted good and are so juicy. (That is also why the Chinese government recently condemned dim sum as not being a particularly healthy food, much to the outrage and dismay of teahouse fanatics throughout the country.) Pork and its derivatives are in almost every recipe in Classic Deem Sum, which means, if you are Muslim or you are cooking for an Islamic friend, I’d suggest you not make dim sum out of this book.

However, if there are no dietary prohibitions against the pig in your chosen religion or lifestyle, I cannot suggest more strongly that you look up this book on Bookfinder, and pick yourself up a copy. While it is sadly, and unjustly out of print, there are quite a few copies available, including first editions and copies signed by Henry Chan himself, if you are into collecting such things.

Until you can get your hands on a copy of the book, however, high thee hence to the nearest dim sum palace, pour yourself some tea and enjoy some dumplings and buns.

And remember–even though I disagree with Emeril Lagasse on many points, I concur with him on this point:

Pork fat rules.

Global Gastronomy

For geeks, bloggers are some of the coolest people on earth.

(Don’t you even take the word, “geek” as an insult. I mean it fondly, and I say it lovingly, and I include myself in that category. Face it, if you sit and write about food–or whatever topic it is you are passionate about–all the time and don’t get paid for it–you are a geek.)

Anyway, why do I say this?

Well, because not only do I learn a lot of interesting stuff by reading blogs, but I have found a lot of food bloggers willing to compile lots of information that is useful and interesting, but which is a hell of a lot of work.

A fine example is the new blog, Global Gastronomy, put together by Biscuit Girl, who also pens You Gonna Eat All That?.

Global Gastronomy is not a typical blog, but instead, is an alphabetical clearinghouse of Internet resources for recipes from every cuisine imaginable.

For the moment, she is only posting resources in English, and she says that the “A’s” are done.

It is a huge undertaking, and I applaud her efforts and vow to give her whatever assistance I can–because I think that there is great value in this project.

So–good on you, Biscuit Girl–keep up the good work!

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.