The First Pesto of the Year!

It does sound a bit early for pesto, at least, when we are talking about Southeastern Ohio, and I just planted my big self-watering planter filled with pesto plants on Saturday.

However, my CSA farmers are clever; they have several greenhouses, one with hot water pipes running under the beds, so they started some genovese basil back in March and lo and behold, great bags of it were ready for sale on Saturday. Needless to say, I picked up two bags, along with some thinner than a pencil shoots of asparagus from another farmer, and resolved to pair the two in several different ways through the week.

Several different ways, indeed, though pesto was the very first–it had to be. The last of my frozen pesto was gone–and as good as it is in the deep midwinter, the frozen pesto still is not as wonderful as the stuff is fresh. I bought up bunches of green garlic to go in the pesto, and broke out the Parmesan cheese, olive oil and pinenuts. (From Italy, California and somewhere out west, respectively–not local, but until Ohio producers start making real Parmesan, growing and pressing stupendous olives and growing me some pinenuts–and these things, due to climate, are not going to happen–I am never going to have truly local authentic pesto. That is fine with me, since most of my staple items are coming in from local producers at this point.)

For dinner Saturday night, which was cooked within twenty-seven minutes, we had thinly sliced chicken breast sauteed with onions and green garlic. When the chicken was mostly done, I added about a third of a pound of the tiny asparagus spears, and stirred them about until they deepened in color and became crisp-tender.

I made the sauce, which was not a pure pesto, right in the pan that the chicken and vegetables were cooked in.I deglazed the pan first with sherry, then with a bit of chicken broth, and thickened it with about a quarter of a cup of heavy cream. I allowed it to reduce for about five minutes, and then slowly added the pesto which stood at the ready in the food processor tablespoon by tablespoon, until it all smoothed out and thickened and became a creamy, pale golden-green ambrosia redolent of garlic and basil, with the sweet nuttiness of the sherry bringing out the flavor of the pinenuts.

After the penne was done, I dumped it in the pan and tossed it all together. There was just enough sauce to coat everything and make it all happy. (Yeah, the penne was Italian too–I had meant to pick up some of our local, delicious fresh Rossi Pasta, but got involved planting basil and tomatoes instead. Next time, it will be Rossi. I promise!)

Since I was cooking so quickly and on a deadline, I have no clue of exact amounts to write out a perfect recipe, but I can approximate it in case anyone wants to try and replicate it. (Since I have never written down a basil pesto recipe with amounts–because I go by feel–I am linking to Elise’s at Simply Recipes. Her amounts look close enough to mine to work right, though I will say, I used green garlic in mine instead of the regular mature kind–and it made the recipe a bit different. A little more delicate, and with an interesting paler shade of green.)

This is my second entry into Kevin’s Asparagus Aspirations event. (My first one was Meena’s Stir Fried Asparagus and Lamb.)

If you are really into asparagus, as I am, you should go check out the collection of recipes he is amassing with the help of the food bloggers of the world. It is really an amazing amount of green goodness. And hey–if you really like asparagus, send in your favorite recipes, too.

Penne with Chicken, Asparagus and Creamy Pesto

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 medium yellow onion, cut into half and sliced thinly

4 stalks green garlic, white and light green parts sliced thinly

1 whole boneless skinless chicken breast, trimmed and cut into 1″ long, 1/4″ wide, and 1/4″ thick slices

1 teaspoon dried red chile flakes

1/3 pound super-thin asparagus spears trimmed and cut into 1″-2″ sticks

about 2 tablespoons dry sherry

1/4 cup chicken broth

1/4 cup heavy cream

1 recipe basil pesto, made in the food processor–it should equal 1 cup or so

salt and pepper to taste

1 pound penne pasta, cooked al dente

Method:

Heat olive oil in a deep, wide saute pan. When it is hot, start sauteeing onions, and when they are golden, add the garlic. Stir until the garlic is well-scented, about a minute and add the chicken pieces. Allow chicken pieces to brown on one side, then turn over. Sprinkle with the chile pepper, and stir well.

Add the asparagus spears and stir until they deepen in color.

Deglaze pan with sherry, and allow alcohol to boil off.

Add chicken broth and stir, allow it to reduce slightly.

Add cream, and stir, allowing it to reduce slightly.

Add the pesto by tablespoons, stirring to incorporate between each addition. When all pesto is added, give the sauce a taste, and correct seasoning with salt and black pepper to taste.

Dump in the drained penne, and stir and toss to coat everything with the sauce evenly. Divide between four warmed bowls.

Serves four with light seconds for one or two people.

Note: If you want to be fancy (I didn’t have time for fancy Saturday night, unfortunately), you could make a chiffonade of basil leaves (stack basil leaves together, then roll up like a cigar, and slice thinly–the slices will unfurl into tiny green ribbons) and sprinkle the top of each serving with a shower of it. It would look awesome, and taste nice, too.

Reminder: The Spice is Right II–“Sweet or Savory?”

Hey, all you spice fans out there–this is just a quick reminder that the deadline for the second edition of The Spice is Right: “Sweet or Savory?” is next week, on the 15th.

You have exactly seven days to post your entry onto your blog and email me your name, your blog name, and the link, so I can include it in the roundup.

For general rules, look here, and for an explanation of what I mean by “Sweet or Savory,” take a glance here.

I’ve already gotten a few really neat entries, and am looking forward to some more.

Oh, and for those who are participating in the Eat Local Challenge–it would be really cool if you worked to fix the two challenges together!

Grubbing in the Dirt

It is hard for me to imagine talking about local, sustainable foodsheds without talking about gardening.

The two go hand in hand.

And speaking of hands, there is no greater pleasure on earth for me, (other than tearing into a freshly baked loaf of whole grain bread, steaming and fragrant from the oven) than sinking my hand deep into sun-warmed soil, and planting something beautiful and edible in that fragrant, fertile bed.

I don’t really understand people who don’t like gardens and gardening. Being outside, in the open air, with the sun on my face, and the wind at my back, the sounds of birdsong filling my ears and the thousand shades of green that the natural world cloaks herself in dazzling my eyes, is a great comfort to me, and fills me with quiet joy.

I reckon that I’ve been a gardener since I could walk, toddling after my mother, making furrows in the dirt with chubby fingers, and carefully covering seeds she planted, then patting the earth firm, “like tucking the flowers into bed,” as Mom would say. And if I wasn’t following Mom, I was at Gram’s side as she instilled in me her principle for foiling weeds and having the prettiest porchboxes in the neighborhood. “Crowd the flowers in, Barbara,” she’d say as she tucked petunias, geraniums, allyssum and coleus tightly into her green enamelled metal porch boxes. “Then feed them well, and water them,” she’d say, “and when they grow, they will tumble all over each other, and spill out of the box, and cover the box and the railing with blooms. Their roots will grow together like one plant, and will crowd out every weed.”

Or, if not Mom or Gram, I’d be padding barefoot along garden rows behind Grandma or Grandpa, as I helped plant corn with the antique contraptions that Grandpa saw in a book somewhere and built in his woodshop, or as I picked green beans off their neatly trellised vines with Grandma. Sometimes, I’d just patter through the garden on my own, enjoying the warm kiss of damp red clay under my toes and the scents of ripening tomatoes mingled with the well-rotted perfume of cow manure and chicken bedding used to dress all of the plants. I remember running through the stands of corn, placed in perfect rows, laughing as the tassles danced in the wind and the leaves struck my face, as I played imaginary games with the crows who called overhead in a chorus of raucus voices.

I simply couldn’t keep my feet and hands out of the dirt growing up. I even inveigled myself into the neighbor’s gardens and helped plant and prune, weed and tend, trim and water. Flowers or fruit, herbs or vegetables–it didn’t matter. I loved them all, and dearly.

Everywhere I have lived, I have had one sort of garden or another, and I usually grow flowers and herbs in equal measure.

My first herb garden was when I was in high school, and I saw small herb plants neglected and alone in a local nursery in Charleston, West Virginia. Rosemary, sage, thyme, chives and oregano came home with me that day, and I put them in a row of pots on our back steps, where the sunwarmed brick would hopefully simulate the rather dry, very warm Mediterranean climate that these plants favored.

Those herbs became an object of interest to my parents, the neighbors and the rest of the family. The only herbs most folks grew in town around us were dill for pickles, catnip for cats and maybe some feverfew because it was pretty. Herbs were not popular then, not with West Virginia cooks, nor with gardeners, so folks came to see what I was about.

The only lady who knew at all what those herbs were and what they were for was old Mrs. Abdella, the grandmother of some of the kids I went to school with. She was Lebanese, and she knew quite well what I was growing, and when she heard, she came by and had me follow her to her backyard, where I was thrilled to see larger versions of my potted baby herbs sprawling over the landscape, mostly in place of a lawn. “You going to cook with yours?” she asked me, her dark eyes twinking.

“I aim to, ma’am,” I answered.

Nodding, she pointed to the back gate that opened into the alleyway. “Until yours grow and get big, you come here and pick–just come through that gate, anytime of day, and I won’t mind. I have enough for the whole neighborhood, if they only knew how to use it.” She rolled her eyes, and snorted. “So, I share with you, eh?”

Mrs. Abdella had been the terror of the neighborhood kids for years, threatening many curses upon any child that dared think of opening that back gate or even stepping a toe on her lawn, so I felt rather as if the Wicked Witch had just transformed into The Herb Fairy in front of me, and instead of flapping her apron and screaming imprecations in a couple of languages, was smiling at me as her gnarled fingers stroked her plants lovingly.

Needless to say, when Grandpa loaded us down with vegetables that summer, as he always did, and we distributed bags anonymously to the neighbors, I made sure that Mrs. Abdella’s bag had lots of extra tomatoes, squash and eggplant, and I always left it at her back door, with a smiley-face drawn on the bag with magic marker.

Over the years, I have made gardens in the most unlikely of places.

In the last house I shared with Morganna’s father, I made a garden in a foot and a half wide strip of hardpan that stood between the house and the curb of the alleyway it fronted. It was the width of the house–about twenty feet or so, and was nothing but baked subsoil, in which only dandelions and thistle could grow. When Morganna was about five months old, I remember sitting on the porch with her, surrounded by asphalt and concrete, looking across the alley at the middle school I had attended years ago, with the brick building and chain-link fence looking prison-like, and being utterly despondant, as I longed for the sight of green. I looked down the street jealously at the wee, postage-stamp sized yards of the row of apartments that made up the little working-class to poor neighborhood, and wished I had just that much room. What I could plant in it!

Well, what I had was that depressing strip of baked dirt.

I ended up calling Mom, and after saving up my money, I had her bring her digging tools, and take me to the nursery, where I bought cow manure, topsoil and a small bag of gravel. And with a pick and shovel, I rooted all of that hardpan out, sweating like a pig, and cursing like a sailor while Mom kept Morganna occupied. I grubbed about two feet down, and then treated the resulting trench as if it were a long porchbox. I sprinkled gravel in the bottom for drainage, and then mixed the manure and topsoil together, and shovelled it in.

That was the first day, and in subsequent days, Mom and I planted every kind of culinary and scented herb we could find. She got so into the project she bought all of the plants and gave me a bunch of her old terra cotta flower pots so we loaded up the porch, too. We planted morning glory seeds in the back, so they clambered up the porch railings to the porch roof, and made a spot of shade to cool the glare from the alley. Dill, bergamot, mint and oregano stood tall and regal in the back, with thyme and creeping chammomile spilling over the curb. In the middle, basil, rosemary, Greek oregano and lemon balm grew in profusion, while at the corners, chives stood watch, thier pale purple blossoms nodding in every breeze. Nasturtiums bloomed where the thyme hadn’t spread yet, and borage’s sky-blue flowers cooled me with the scent of cucumber. Pots of lavender and more rosemary lined the steps, while scented geraniums stood sentry along the porch rail.

By midsummer, it was beautiful. Everything grew in grand profusion, tangling and twining around each other as I applied Gram’s principles of crowding out weeds in a porchbox to a grand scale. My cooking improved immensely, since I could just run outside and pick handfuls of whatever herb struck my fancy, and when I nursed Morganna, I could go without a shawl, because no one could see past the screen of morning glories that tumbled over the porch to the roof, and cascaded back down in a curtain of green heart-shaped leaves and sky-blue blossoms. The smell of baking asphalt was covered by the scent of rich earth and green and growing things, and in the evening, when I would strap Morganna to my back and tend the garden, the neighbors would stop and talk, marvelling at the transformation of that depressing squat house that sat crooked on its foundation, to a magical cottage covered with a verdant cloak.

Since then, I have gardened in boxes, crates and pots, in plots of earth large and small, and I have a few observations.

One–I despise the American obsession with perfectly clipped, tidy green lawns. A more wasteful, stupid preoccupation with perfection I cannot imagine, and a worse use for a good bit of land I cannot fathom. The amount of petrochemicals poured out in the form of fuel for noisy, air-polluting lawnmowers and trimmers, in the form of fertilizer, herbicide and insecticide in the creation and maintenance of a wide expanse of perfectly manicured green grass is horrendous.

I think that Americans would be better off getting rid of lawns and planting other stuff in thier place. Preferably some vegetables, fruits and herbs, but I wouldn’t ever hold it against someone for planting flowers. The problem with my wish is that gardens require tending, while lawns, once established only require mowing, which now, one can do sitting down, with little to no effort at all.

But look at how much local, sustainable food could be grown, even in a small yard. And think of how good it would taste!

A second observation is this–gardening creates community–something that is lacking in many American neighborhoods today.

But, it is true. I have never had so much luck meeting neighbors as when I am engaged in gardening. People are drawn to plants, and the cultivation thereof. Many people regard the ability to grow plants well almost as some sort of magical gift, and will stop and ask about it. The colors, scents and if you grow vegetables or fruits and share them, flavors, of a garden make people slow down and want to talk. And talk is good–it is the first step in creating bonds of fellowship that grow into a real community feeling, which is necessary for humanity. We are not meant to live in isolation, but instead, in groups–that is what we evolved to do.

My third and final observation is that gardening creates kinship with the rest of nature–and that is something that is also sorely lacking in the urban and suburban word of modern America. While some gardeners rail against nature in the form of deer eating their tulips, others are enchanted by the nesting habits of wrens or the appearance of butterflies in the echinacea in the morning and the fluttering of moths near the same flowers at night. Learning to work with the natural world–the world of which we humans are a part, no matter how hard we try to ignore or deny that fact by living in air-conditioned homes and driving in closed cars to malls that are the very epitome of artifice–reforges the bond humanity must reclaim with the environment, if we are to reverse some of the damage we have done with pollution, overpopulation and soil depleting agricultural practices. Gardeners learn volumes of information that cannot be read in books or on blogs, that must be absorbed through the fingers, and toes, through the senses of sight, scent, taste, hearing and touch, that cannot be conveyed by mere words.

We humans grow roots when we garden, just as surely as the plants we lovingly tend do. We plant seeds in the earth and find seeds planted within ourselves, and as we watch our gardens grow, we, too, are made anew.

That is the principle of sustainability writ small, and in a person’s heart. Learning to live rooted to place, learning to live within the rhythyms and cycles of nature, learning to nurture life in all forms, are all lessons that a garden can teach us.

I write these words as I look out upon the expanse of our back lawn. Green swarths of grass cover a steep slope–too steep to till, and I dream. Next year, or the year after, that slope will be terraced, and the soil will be mixed with compost and manure, and our fingers will sink into it, learning the secrets that it holds. We will plant flowers, fruit trees, vegetables and herbs in vast profusion, with glee, and watch as what was once just an unuseable hill grow into a place of fertile abundance.

And I can tend the herbs again, with a baby strapped to my back, with the sun on our faces and the breeze in our hair, and it will be good.

Oh, how can anyone prefer a lawn to that?

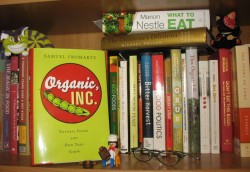

The Locavore’s Bookshelf: Organic, Inc.

Samuel Fromartz’ excellent and well-researched book, subtitled, Natural Foods and How They Grew, takes a look at the rise of organic foods from its its infancy as a niche agricultural method practiced by a very few who were often laughed off as cranks and crackpots, to the continually growing, increasingly corporate sector of the food industry. Along the way, he puts the research surrounding organic agricultural techniques, the nutrition content of organic foods, and pesticide residues in the bodies children under the intense focus of his microscopic attention to detail.

It all sounds so very boring, doesn’t it? All of this talk of corporate buy-outs and the ancient history of the organic movement, mixed with a healthy dose of Rachel Carson’s gloom and J.I. Rodale’s visons of health seems guaranteed to put a body to sleep, with or without a glass of warmed organic, rBGH-free milk.

I was surprised to find that this book wasn’t boring at all; in fact, it is written in a style that balances the dogged determination of an investigative journalist ferreting out truth from a tangled skein of myth and misdirection, with the passion of a man on a personal quest. Fromartz starts the book with his own personal background of how he came to want to tell the story of the growth of natural foods from a hippy dream to big business, and from the beginning, he draws the reader in with the power of his electric prose and his ability to convey personality as he tells the individual tales of organic pioneers as a microcosm of the whole movement.

He manages to, in the course of 259 pages, spin the tales of how farmer Jim Cochran came to nearly single-handedly create the methods of growing organic strawberries while making a profit, how soymilk came to be widely available in most supermarkets in the US, and how Kellog’s, current purveyor of empty calorie sugar-frosted cereal horrors, started out as a health-food manufacturer.

He also outlines the recent split in the organic movement between the Organic Consumer Association and the Organic Trade Association over a court case brought by a neo-luddite organic blueberry farmer from Maine, which threatened to completely disassemble the current USDA Certified Organic labelling rules. Fromartz gives a full accounting of the case in true, unbiased journalistic form, filled with the nuances and shades of grey that all court battles which are essentially about semantics, which led me to have a bit more sympathy with Arthur Harvey’s (the blueberry farmer) case, However, I still have to say most of my sympathy lay with the OTA, rather than the OCA. The media fear-mongering media blitz carried out by the OCA that trumpeted the “35 synthetic chemicals allowed in USDA Certified Organic foods” was not based upon solid facts, but rather were the attempts of extremists to get the public to blindly follow their lead, thus setting back the organic food movement by about twenty years.

(For my take on the OCA’s stance on the chemicals, as well as my own listing of the chemicals involved, including annotations on what they are, what they are used for and how the National Organic Standards Board approved of their use, see my 5-part series of articles, written last October: Those Darned Chemicals, TDCII: What is Really Going On Here?, TDCIII: What Are Food Additives, and Why Worry About Them?

,TDCIV: What, Me, Worry?, and finally, TDCV: The Final Confrontation, which contains the complete annotated list of the thirty five synthetic chemicals which the OCA took issue with, along with my final comments. This essay and listing is linked at the OTA website.)

Be that as it may, Fromartz’ book is an outstanding read, and well-worth the time of anyone who is interested in eating locally, organically, or just plain better. Parts of it are funny, parts of it are sad, and parts of it will undoubtedly make many readers angry.

Which is a good thing, as there are many reasons for consumers to become peevish with not only conventional agriculture and factory farming, but also with some large organic producers, such as Horizon Organic, which produces “organic” milk in a factory farm setting.

But, while some of the facts presented in the book will ruffle some feathers, others offer hope for the future of American food, so one need not worry–this is not a tome filled with gloom and doom.

Local Spring Flavors Dance Together in a Global Fusion

There are few flavors more evocative of spring than asparagus, lamb, green garilc and mint. And, as it so happens, they are also extremely local flavors as well; all over the farmer’s market on Saturday, there were bundles of asparagus, ranging from thumb-thick spears to dainties thinner than a pencil. Lamb, too, is a traditional spring food enjoyed all over the world, and I had some tiny lamb flank steaks in my freezer from Bluescreek Farms Meats wiating for something special to happen with them. Green garlic tempted from several booths at the market as well; I bought enough of it to last a week. (The farmer quipped to me, “You got vampires?” “Nope,” I answered, “just a bunch of garlic-loving eaters.”)

And nothing, but nothing is more local than the mint that is springing up all over my perennial bed. We inherited it from the house’s former owners, so I have no real idea what variety of mint it is, though from the color of its leaves and stem, and the shape of it, I think it is probably chocolate mint. Some think it was named for a chocolatey flavor, which is something I cannot personally discern; I think it was named for the dark reddish brown of the stems and the veins in the leaves.

Whatever kind of mint it is, there is a lot of it, and it is very strongly flavored. A little of it goes a long way.

What to make with this abundance of springtime joy? What sort of dish could utilize all of these happy flavors in a cohesive fashion?

I immediately latched onto the idea of a stir fry for several reasons. For one thing, lamb flank steaks are perfect when they are sliced across the grain and stir fried, and it just so happens to be my favorite method of preparing that particular cut of meat. Besides, stir frying asparagus is also a very fine way to showcase a flavor that is to me, the epitome of spring.

So, a stir fry it was to be, but in what context? Green garlic obviously will do well in a stir fry, but mint?

It was the mint that got me to thinking.

I had read about Chinese food in India on Meena’s blog, Hooked on Heat a while back, and the thought that I should attempt some sort of Indo-Chinese fusion had been simmering in my head ever since then.

“Why not,” I thought to myself, “do an Indian-Chinese fusion stir fry?”

Fusion cuisine can be either some of the best food in the world when it is done well and with care, or a nasty, messy glop when executed poorly. In my opinion, there is seldom any comfortable middle ground.

In my opinion, the best fusion foods are those that arise naturally from the interaction between two or more food cultures. This intaction often comes about because of immigration, but it can also come about through trade in foodstuffs.

India and China have a long history of cultural interaction between the two countries, both directly, through immigration and indirectly, through trade and trade routes. Both countries have long culinary histories, with very diverse regional differences in cooking style and flavors. And, as Meena pointed out in her post–there already exists in India, an Indo-Chinese fusion that came about when Chinese restauranteurs did what they always do in whatever country they settle: cook their foods to reflect the foods of their new homeland, and the tastes of their customers.

My general personal guidelines that I use in determining whether or not I will attempt a culinary fusion between cultures is to look at the two cusines and pick out commonalities. If there are enough commonalities between them, then a fertile and flavorful fusion is more likely to be successful.

In the case of Indian and Chinese food, and in the ingredients I had chosen, there are a great deal of commonalities.

Lamb is one of the most commonly eaten meats in India; it is also popular in some parts of China, noteably the northern and western provinces.

Garlic of any sort is popular in both cuisines.

Mint is extremely popularly used in Indian foods; while it is not common in Chinese foods, there is still a tradition of using fresh herbs, noteably cilantro, in garnishing stir-fried dishes.

Finally, while asparagus is not generally considered either a Chinese or Indian vegetable, I have cooked it in the contexts of both cuisines to excellent effect in the past.

So–a fusion it was to be.

What other ingredients would I add as I performed an alchemical marriage between Indian and Chinese cookery?

Ginger is an obvious ingredient; it, like garlic, is extremely prevalant in both culinary traditions.

What spices should I use? Black or white pepper would be the perfect answer–they are common to both cultures–but, since I have discovered I am allergic to peppercorns, I saw no reason to use them. Cardamom popped into my head first; its flowery scent would go well with the verdant snap of the asparagus and it always tames the gamy richness of lamb. Coriander, which is used sometimes in red-cooked dishes, and is, of course, the seed of the cilantro plant, is another good idea. It also pairs well with cardamom, because its lemony flavor blends seamlessly with the floral qualities of cardamom. My third and final spice was a tiny bit of fennel seed. It has a similar aroma and flavor to star anise, which is favored in Chinese cookery, and when used sparingly, heightens the effect of any other slightly sweet spices that are used with it.

I decided on premium light soy sauce, and after sniffing my ground masala mixture of cardamom, coriander and fennel in tandem with it, Shao Hsing wine. The sweetness of the spices brought out the nuttiness of the rice wine perfectly, while the soy sauce would add depth, umami and a salty richness to the entire dish without being overpowering.

I have to admit to being somewhat nervous when I served the dish to Zak and Morganna, since it was very much an experiment.

However, my fears were groundless. Once they smelled the dish and then tasted it, there was no dissent: it was a very good marriage between fresh, locally available foodstuffs, and two distant cultures.

My fnal proof that they liked the dish: there were no leftovers in evidence. Every scrap of it was eaten.

So, I want to thank Meena for giving me the inspiration for trying such a fusion, by naming the dish for her.

Meena’s Stir Fried Asparagus and Lamb

Ingredients:

3/4 pound lamb flank steaks, trimmed of silverskin and excess fat, and sliced thinly across the grain

1 tablespoon premium light soy sauce

1 tablespoon Shao Hsing wine or dry sherry

2 tablespoons cornstarch

1 teaspoon coriander seed, 1/8 teaspoon cardamom seeds and a pinch of fennel seeds, ground together and divided

3-4 tablespoons peanut oil

4 stalks green garlic, white and light green parts sliced on the diagonal 1/4″ thick, green tops sliced on the diagonal 1″ long, separated

1 1″ cube fresh ginger, cut into thin slices about 1″ long and 1/4″ wide

1 tablespoon Shao Hsing wine

1 tablespoon premium light soy sauce

1 pound very thin asparagus spears, trimmed and cut into 2 1/2″ lengths

2 tablespoons chicken broth

handful of fresh mint leaves, roughly chopped

Method:

Mix together the lamb, the first quantities of soy sauce and wine, and 1/3 of the spice pixture with the cornstarch and toss until well coated. Marinate at least for twenty minutes, but no more than an hour.

Set aside the rest of the spice mixture.

Heat wok until it smokes, add oil and heat until it shimmers. Add garlic and ginger and another third of the spice mixture and stir fry for about one minute, or until very fragrant.

Add lamb, reserving any liquid marinade in the bowl. Spread into a single layer on the bottom of the wok and allow lamb to brown on the bottom–about one and a half minutes. Stir fry with the aromatics until the cornstarch marinade browns on the sides and bottom of the wok. Add second quantities of soy sauce and wine, and deglaze the cornstarch, stirring the meat in well.

Add the asparagus, stir frying all the while, until it begins to deepen in color.

Add two tablespoons of chicken broth, and stir fry until sauce clings to the meat and asparagus. Sprinkle the reserved green garlic tops and mint leaves over, stir to wilt and combine, and sprinkle a pinch or two of the last third of spice mixture over the dish, stirring once more to combine.

Scrape into a heated platter and serve immediately with the steamed rice of your choice.

Note: This dish is my entry for Kevin of Seriously Good’s “Asparagus Aspirations” blog event. If you are into asparagus, go check out the great lists of recipes for the noble harbinger of spring that participants from all over the world have sent in so far.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.