Book Review: Modern Asian Flavors

Most of my current focus in building a library of Chinese cookbooks has been on out-of-print or difficult to find volumes. However, now and again, a new cookbook comes out that I find to be intriguing, so I pick it up and see what it is about.

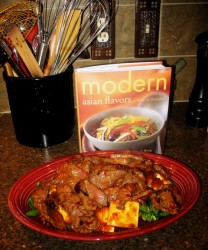

Modern Asian Flavors: A Taste of Shanghai, by Richard Wong, is one such book.

Richard Wong, a native of Shanghai who grew up in the United States, is the founder and owner of chinablue, a company which creates a line of popular Shanghainese sauces, oils, glazes and dressings which are sold in upscale markets, gourmet stores and groceries around the country.

I am actually glad that I didn’t know this when I picked up the book and looked at some of the recipes; I would have assumed that the book was just a means by which Wong meant to market his sauces, but none of the recipes feature his bottled products. Instead, instructions are given on how to make basic sauces, dressings and glazes from scratch to use in creating the later recipes.

I don’t know much about Shanghainese foods, except to say that Shanghai, which was once a city that was populated by Chinese, European, Indian and Japanese people, and as such, the food of Shanghai has always shown a very global influence. I have grown to understand that Shanghainese food often uses a great deal of sugar, and as such, many of the dishes common to the region have a strong sweetness to them. Other strong flavors are used to compliment the sweetness: soy sauce, sesame oil, black beans, scallions and red chile paste are used copiously in many of the recipes in this book.

The one thing I really didn’t like about the book was the way the recipes were written. There is not much emphasis on technique and proper stir-frying in the book, and I think that is a definate lack when it comes to a book presenting Chinese food to an American audience. Granted many of these dishes are fusions of Chinese flavors with European techniques or ingredients, but still–I think that any really good Chinese or other Asian cookbook should delve deeply into technique when they are aimed at a Western audience–simply because the techniques used in each cuisine are so different.

A plus on the side of the book was the beautiful food photography by Noel Barnhurst. The photographs are spare, with delicately arranged foodstuffs presented on dinnerware of muted colors. The food itself, often vividly hued, is the centerpiece, and the backgrounds fade into soft focus, allowing the brilliant tones and linear shapes of red and yellow peppers, for example, to draw the reader’s eye effortlessly.

The proof of any cookbook, however, is in the recipes, and judging by Zak’s reaction to the one recipe I have tested from Modern Asian Flavors so far, I think that this book “has the stuff” to be considered a worthy addition to my Chinese cookbook collection. However, I have to say that I didn’t follow the recipe exactly for the dish, because even though it is billed as a stir-fry, the instructions as written, which require that the cook put marinated meat and a half-cup of sauce into the wok and “stir-fry” it, would not result in either the flavor or texture of stir-fried meat. It would result in quick-braised meat–which would have a totally different texture and flavor.

I also added a layer of gai lan simply stir fried in peanut oil to the dish, so as to have a more complete one-dish meal.

The final change that I made was to the Shanghainese Red Pepper Sauce, which one makes before making the rest of the dish. The original recipe called for 1/2 cup of sugar dissolved in a 1/4 dry sherry (I used shao hsing wine, needless to say), six tablespoons of soy sauce, and two teaspoons of sesame oil to which two tablespoons of chile garlic paste and shredded ginger have been added.

I found that the sweetness was overpowering until I added a further two and a half tablespoons of chile garlic paste. Once the heat balanced the sweetness, however, the sauce was divine. Zak informed me that I would be making this particular dish again, and hopefully soon.

Red Pepper Beef and Tofu Stir Fry

Ingredients for Shanghainese Red Pepper Sauce:

2 teaspoons cornstarch

6 tablespoons soy sauce

1/2 cup sugar

1/4 cup shao hsing wine

2 tablespoons chile garlic paste (or 4 1/2 tablespoons as I made it)

2 tablespoons finely grated fresh peeled ginger

2 teaspoons toasted sesame oil

(You are supposed to cook this sauce; however, I didn’t do that–I saw no reason to cook it twice, as I was using right away in a cooked dish.)

Ingredients:

(Optional: 1 pound young gai lan, washed, trimmed and cut into 2″ long chunks–this was my own addition)

12 ounces bomless rib-eye steak, trimmed of fat and cut into 1/8 inch thick slices across the grain (I used top sirloin)

2 tablespoons cornstarch (again, this is my addition)

1 cup Shanghainese red pepper sauce, divided

1/2 cup plus two tablespoons peanut oil (I used 6 tablespoons of oil total–the half cup to fry the tofu was unecessary)

14 ounces extra firm tofu, cut into 2 inch squares that are 1/4 inch thick

Method:

Toss beef with 1/2 cup of the pepper sauce, and the two tablespoons of cornstarch. Set aside for at least twenty minutes.

If you are using the gai lan, heat wok, and when it smokes, add 2 tablespoons of peanut oil. Add gai lan, and stir fry until the stems are tender crisp and the leaves are wilted and velvety. Scoop out of wok onto a warmed serving platter, and spread the greens evenly over bottom of platter.

Heat wok again, add 2 tablespoons of oil, and lay tofu squares into wok. Allow to brown on one side, flip them over, and allow to brown on the other side, stir frying carefully so as to not break the tofu apart. Scoop out of wok and layer browned tofu on top of gai lan.

Heat wok again, add the remaining oil, and then add meat. Leave any liquid marinade in the bowl and reserve it. Allow meat to brown on the one side about one minute before turning and flipping and stir-frying. After cooking for about a minute, add the marinade from the bowl and the rest of the sauce, and cook, until the meat is medium rare and the sauce is thickened and fragrant. Pour contents of wok over tofu and gai lan and serve immediately with plenty of steamed rice.

It Isn’t Just a Matter of Culinary Illiteracy….

I know that both Kate at The Accidental Hedonist and Elise at Simply Recipes have covered this interesting piece in the Washington Post about the “dumbing down” of recipe writing, but I had a few thoughts on the subject that I wanted to share.

Way back in the day, when I was a journalism student, working on the college newspaper, which was run pretty much like a professional paper, I remember getting into a big fight with my instructor over my use of the word, “myriad” in a news story.

You see, we had been told that we were supposed to be writing on an eighth grade reading level, because that is the level most Americans are comfortable at reading, and apparently, “myriad” was not a word that eighth graders regularly encounter.

The instructor, who wasn’t my instructor, actually–he taught another section of the news writing class, but he was a busybody and liked to hang out over any students’ shoulders while they were working–looked over my shoulder and just as I typed, “myriad,” pounced on it with a jabbing finger. “That,” he said more loudly than necessary, “is above an eighth grade reading level.”

I disliked the man intensely anyway, in large part because he once scolded me for having a filthy mouth when I had cussed a blue streak after the VDT (yes, it was way back in the day) had just eaten the story I had worked an hour on five minutes before deadline. I could have just used a different word. I could have just changed it until he started vulturing over someone else’s shoulder, and then put it back. But no. I narrowed my eyes, leaned back and looked up at him with a Clint Eastwood steely glare. I even pitched my voice low, like “The Man With No Name,” and said, “Am I writing for eighth graders?”

“Well, no,” he admitted.

“Who am I writing for?” I pressed.

“College students.”

“They had to pass the eighth grade to get here, didn’t they?” I said, nostrils flaring.

“Well, yes, but you know, when you get out in the real world, you can’t use words like myriad,” so you might as well get used to not using them now,” he countered. His position was logical, if defeatest. I refused to go gently into that long night.

I turned in my chair and looked him in the eye. “Well, when I go out into the real world, I will write for idiots. While I am here, writing for college students, I will be damned if I spoon feed them middle school pablum just because they don’t want to think. If a college student doesn’t know what the word “myriad” means, then they bloody well should, and if they don’t, they can look it up in a dictionary.”

I turned my back deliberately on him and went calmly back to writing.

He harumphed, and stood over me for a time. I think he wanted me to turn back around. But, as far as my nineteen year old self was concerned, the case was closed.

Finally, he said, “Well, if you feel that way, I suppose then that you can use the word myriad. We’ll just see if the copyeditors let it stand, though.”

I kept writing, and he vultured off to harass some other student.

The next day, my story appeared, and the word “myriad” was intact. Apparently the copyeditors agreed with me that it was an appropriate word to use in a college newspaper.

I see the issue of my fight to use the word “myriad” and the fact that recipe writers are having to leave off using culinary terms such as “fold,” “cream,” (as in, “cream together butter and sugar”) and “dredge” as all of a piece.

Many Americans are functionally illiterate, and frankly, I don’t see that changing anytime in the near future. Fewer than half of Americans read literature any more, and testable literacy proficiency has fallen dramatically among college graduates between the years of 1992 and 2003. In 1992, 40 percent of college graduates scored at the proficient level, which meant they were able to read long, complex texts and draw sophisticated inferences and conclusions. But on the 2003 test, only 31 percent of the graduates demonstrated reading skills at that level.

When you look at the problems cited in the Washington Post article, such the need to explicate terms such as “fold,” or “saute” intead of using them in writing recipes, in the context of flagging literacy across the boards in the US, you see that the problem is not merely the case that no one is learning to cook from Mamma or the Home Ec. teacher anymore.

It is also a matter of an inablity to read and follow -any- instructions, much less ones that include unfamiliar terms.

The Paper Palate Doings

I haven’t posted links to the stuff I have written recently for the Paper Palate, so, here is a quick catch-up post to get everyone up to speed.

Back on the 21st of last month, I riffed off of a New York Times story that showcased Hedonism and Health, where I urged readers to take their time, enjoy their food and maybe they would find a laid back means to better health and happiness.

The next day, on the 23rd, I talked about The Lonely Life of a Chef, taking as my inspiration a story from The Washington Post.

I also reviewed Chile Pepper Magazine, which is amazingly lively and fun for such a niche publication.

On the 24th, inspired by a guest column in the New York Times, I talked about Alice Waters’ proposed Revolution in the Lunchroom…and the Classroom.

I received the Williams-Sonoma catalog in the mail and noted that lots of Asian cooking equipment was in their pages, but at really high prices, so I wrote about that on March 2nd.

Having head scuttlebutt that there were rumors flying that the Washington Post was planning on getting rid of the Wednsday Food & Dining section, I posted about that on the 7th.

A cute story from the Washington Post made me muse on Kitchen Slang, and wonder if there was any way we could think of an alternative to the overused term, “foodie.”

Stories from the New York Times about health inspectors in the city shutting down the process of cooking food sous vide made me invetigate the issue on the 9th.

A small feature on rabbit meat in the New York Times magazine begged to be expanded upon, so I did so in Rabbit: The Other Other White Meat.

Finally, I found a piece on how grassfed beef yields healthier meat in the Washington Post and similarly expanded upon it.

The Paper Palate isn’t all about me, of course. I also wanted to highlight the work of some of our newer writers while I am at it here.

Cathy Ding illustrates a recipe for chocolate cake from Cook’s Illustrated and has marvelous results.

Beth takes on the potsticker recipe in the same issue of Cook’s Illustrated and comes to the conclusion that while they are pretty good, they are by no means perfect, no matter what the editors of that magazine think.

Bronwen Hanna-Korpi takes on one of Mark Bittman’s recipes, along with her own research and makes a North African dinner to be proud of.

And finally, Stacy Orstein cops to not being Irish at all, but to loving soda bread.

Key Lime Pie is Not Green

Unless, of course, you are one of those infidels who puts green food coloring in it.

In which case, I am not speaking to you.

Key lime pie is properly a rich, creamy yellow, from the egg yolks that enrich the citrus-kissed custard that makes up the filling.

I did not grow up eating key lime pie, but after meeting Zak, I have done my part to make up for many early years of deprivation.

He grew up with the stuff, having been raised in Miami, Florida. So, he knows from key lime pie. And he knows darned good and well that it is not supposed to be green, it is supposed to be yellow.

He is also of the opinion that is supposed to have a graham cracker, not pastry crust, and that meringue should never come near it. Maybe just a little whipped cream, if one must adulterate the sacred key lime pie.

Of course, there are those of the opposing opinion, who are just vociferous in declaring that key lime pie should be in a pastry crust, with meringue on top, to be “real.”

Now that one can purchase key limes outside of the state of Florida, one can easily make key lime pie, providing that one knows what a key lime pie is, and how to make it.

The thing is, not many people agree on that.

I think that this is because no one really knows the history of key lime pie. The first recipe was written down in the 1930’s, but it had been made long before that down in Key West. No one knows who made the first one. Some say it was a sailor who made a dessert that required no baking, since ovens on board ship are rather rare. Others say a ship’s chandler named William Curie had a cook simply known as Aunt Sally, and she invented the pie in the late 19th century. Still others claim that it was inventend in the kitchen of the Milton Curie Maison in the early 20th century.

No one really knows.

What is known is that the ingredients are simple, and were born of the limited resources of the Florida Keys before milk trucks could come to them easily and before refrigeration. The filling for key lime pie consists simply of a can of sweetened condensed milk, four egg yolks, and a varying quantity of key lime juice and zest.

The next question, of course, is what is a key lime and what makes it so special? Well, they are tiny–about the size of a golf ball–and they are yellowish green when ripe. They have an intense floral aroma in the zest and juice and they are a tiny bit sweeter tasting than the regular large dark green Persian limes that you see in the grocery store. Most of the ones you buy now in stores are from Mexico or Miami; a hurricane in 1926 killed the commercial groves in the Keys, and the trees were replaced with Persian limes. Hurricane Andrew, more recently, wiped out many of the remaining commerical groves in Florida. Now, they are mostly seen in backyards of private homes, though, there are still a few commercial groves around the Miami area.

The ones I bought to make this pie, however, came from Mexico. Key limes are not much to look at, but they really pack a punch in flavor. Though, the truth is, you can make this pie with Persian lime juice and zest–it just won’t be quite as unique.

There was no fresh milk in the Keys until the opening of the Overseas Highway in 1930, as there were no cows. So, folks used canned evaporated and canned sweetened condensed milk for cooking. Sweetened condensed milk, invented in 1856 by Gail Borden is the secret to the smoothy, creamy, absolutely stunningly rich filling.

Whatever you do, don’t try to “improve” the recipe and use fresh milk, sugar and eggs, boiled into a custard. It won’t work. It won’t taste right, nor will it have the exquisitely velvety mouthfeel that the sweetened condensed milk gives the filling. Take my advice, and just don’t bloody well go there.

In the old days, the filling wasn’t baked at all. The egg yolks were simply whisked until they thickened and turned a pale yellow, then the sweetened condensed milk was whisked in. Then, in went the key lime juice and the zest. The whole thing was poured into a pre-baked single crust pastry shell or graham cracker crust, and the acid of the lime juice “cooked” the egg yolks by firming them up.

Nowadays, with the worry of salmonella in eggs, most people bake the pie for about 10-12 minutes at 350 degrees to kill any wee buggies that might be lurking in the yolks, just in case. At any rate, that small amount of baking time doesn’t change the texture of the filling in any appreciable way; I have eaten key lime pies both baked and unbaked. I just like to make sure by baking mine these days.

Key Lime Pie

Ingredients:

18 graham cracker squares (that would be when you break a graham cracker in half, into a square instead of a rectangle)

3/8 teaspoon powdered cardamom

5 tablespoons salted butter, softened

3 tablespoons raw or white sugar

4 egg yolks

1 14 ounce can sweetened condensed milk

1/2 cup key lime juice (this takes around a dozen or so key limes)

2 teaspoons finely grated key lime zest

Method:

Preheat oven to 350 degrees F.

In a food processor, crush graham crackers to crumbs. Add cardamom, softened butter and sugar, and continue processing until the mixture looks like damp crumbs.

Dump the contents of the food processor bowl into a 9″ pie pan, and press evenly into the bottom and sides of the pan to form a crust. Bake for 8-10 minutes, or until browned and fragrant. Remove and cool to the touch on a wire rack.

In a mixing bowl, whisk the egg yolks well, until they are thickened and become a paler shade of yellow. Add the sweetened condensed milk, and continue whisking until well combined. Add half the lime juice, and whisk until well combined, then add the rest of the juice along with the lime zest, and whisk just until incorporated.

Bake at 350 for 10-12 minutes. Remove to a wire rack, cool to room temperature, then cover tightly and refrigerate until serving.

Optional:

Whisk together 1/2 tablespoon powdered sugar, 1/2 cup heavy cream and a pinch of cardamom and beat until moderately stiff peaks form. Top the pie and garnish with key lime slices.

Of course, when I come back from Washington DC next weekend, I want to make a Meyer Lemon Pie along the same lines as a Key Lime Pie and see what that is like….

Chicken Tikka Masala and Dr. Who

So, here’s the deal:

I don’t get the whole St. Patrick’s Day thing. I’m barely Irish (I have a couple of Irishmen in the family tree here and there, but not enough to count as Irish), and I’m certainly not Catholic, and I really don’t like the idea of drinking beer with food coloring in it.

And, really, I don’t much care for most Irish food.

Canned corned beef made into hash is a nightmare from my childhood.

I am not so much into cooked cabbage, so there goes colcannon right there.

So what are we doing at our house while everyone else is out celebrating being Irish? Who are we going to celebrate tonight at supper if not St. Patrick?

Who, indeed.

Tonight is the US premier of the new Dr. Who series, and we are celebrating by having traditional British food. So, instead of being St. Patrick’s Day at our house, it is Dr. Who Day, and we are feasting in honor of the last of the Time Lords.

Feasting on what?

Chicken tikka masala.

Well, yeah. It was declared the official dish of the UK back in 2002 by the foreign minister, so there. That makes it, like British.

So that is what we had. I gave the folks a choice between that and shepherd’s pie, and chicken tikka won.

Now, my recipe is a cheater’s version. You are supposed to use leftover tandoori chicken to make the dish, but since I had none of that lying about, I cheated and cooked the chicken in the sauce. (It is said that chicken tikka masala came about when a British diner was served tandoori chicken and demanded a gravy to go with it. I don’t think that was the case. I think it might have been a clever way to use untouched tandoori chicken by turning the leftovers into something else–something tasty. The chicken if reheated it as it was, would be dry–but with a sauce–well, it would be delicious.) It turns out fine that way. I also use less cream than most restaurants, mainly because I want to be able to eat the dish more than once a year. I also spice mine up a bit more than many places, but that is okay. It tastes good that way.

You will notice a certain similarity to this and chicken makhani–that is because I suspect that the sauce for chicken tikka masala is based on the sauce for chicken makhani. (If you clicked on that link above about chicken tikka masala being the most popular dish in the UK, and read the article, you will come across the opinion of Shekhar Naik, owner of the Ambassador of India restaurant in Glastonbury…he says that it is a variant of chicken makhani that was invented in a restaurant in New Dehli. This jibes also with what the waiter at Akbar told us years ago–he said it was his favorite dish and that there were restaurants in New Dehli that served it, and when he went home, he always ate it there.)

So, here is the recipe:

Spicy Chicken Tikka Masala

Ingredients:

2 small, or one medium onion peeled, and roughly chopped

5 cloves garlic, peeled

1 ½ inch piece fresh ginger, peeled and sliced

fresh red chili peppers to taste (1 or 2 small thin ones)

12 cardamom pods, seeds removed and ground

1 tsp. black peppercorns, ground

2 tbs. coriander seeds freshly ground

1 tbs. paprika

1 tbs. dried fenugreek leaves

1 tbs. butter or butter ghee

1 ½ cups water

1 14 ounce can crushed tomatoes

½ cup yogurt

2 tbs. butter or butter ghee

1 cup or less heavy cream

salt to taste

1 ½ pounds boneless, skinless chicken breasts, cut into 1†pieces

handful fresh cilantro, chopped for garnish

Method:

In food processor or blender grind onions as fine as possible. A paste is preferable, but do it as fine as you can. (The Sumeet makes this much simpler.

Grind together garlic, ginger and chili peppers the same as the onions. Keep separate from onions.

Grind all dried spices together.

Heat first tablespoon butter or ghee in a deep frying pan, (nonstick is best) and add onions. Stir and fry until the onions begin to brown. Stir constantly. If they start to burn, add a tiny bit of water.

When onions are brown, add the garlic, ginger and hot pepper paste, and stir, frying for about three more minutes.

Add dried spices, and cook until mixture is very fragrant–a couple of minutes

Add water, and mix together into a sauce.

Add tomatoes, and stir together. Turn heat to low, and cook until your sauce has reduced by one half.

Stir yogurt until smooth, and add to simmering sauce, one tablespoon at a time. Whisk until sauce smooths.

Add butter or ghee, allow to melt, whisk until smooth.

Add cream, and salt to taste.

Add chicken pieces, and simmer on low until the chicken is done and just tender, probably around 8 minutes.

Stir in cilantro and serve.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.