What To Eat When You Read About Curry

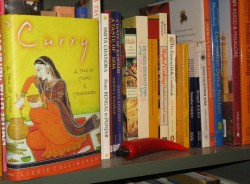

It is all the fault of this book I am reading, you see.

Entitled, Curry: A Tale of Cooks & Conquerors, by Lizzie Collingham, it is a history of the development of the dish known as curry. (Who would have guessed?)

It is also utterly engrossing, at least to a food geek like myself who finds the development of cuisines to be fascinating. I had known much about the Persian influence upon northern Indian cusine, and of course, I knew that it was in the port of Goa that the Portuguese brought the chile pepper from the New World to India where it then spread over the south like a wildfire. But, I really didn’t know that much about the British influence upon Indian food–I knew more about it from the other way around: the Indian influence upon British food. So this book is keeping me occupied, all through the day and night. (Look for a review of it when I am done.)

It is also making me hungry.

So, I am reading it, and it is talking about the Mogul emperors in the north of India, and how they brought the Persian way of cooking rice to India, and brought the taste for using lots of dairy products, fruits, nuts and meat in the cooking, and I thought to myself, “Oh, I need me some of that.”

And then, I got to the next chapter which was all about the cooking of the south of India, and how when the Portuguese brought the chile pepper, everyone was using it in everything along with mustard seeds, ginger and cumin and I said, “Oh, damn. I need some of that, too.”

So, I put down the book, went to the kitchen, dug around, then headed off to the grocery store and picked up a few things.

Because I had to have curry. I just had to. Had to, had to, had to–because there is nothing worse than reading about all of these delectable dishes and not being able to taste any of them.

So I fixed up two dishes, plus some turmeric-scented basmati rice: one to represent the northern, Persian influenced style of the Mogul empire, and the other to stand up for the fiery, intense vegetarian foods of the south.

I decided on lamb kofta in a yogurt sauce with pomegranate and mint, and aloo gobi.

Ah, aloo gobi. It had been too long since I had eaten it.

Aloo gobi is quite simply potatoes cooked with cauliflower in a turmeric-colored, very thick curry sauce. Many versions of it that I have eaten in restaurants that cook primarily northern Indian food have been quite tame, but my favorites have been the ones that are redolent of mustard and cumin seed, snapping with fresh ginger and browned onions and filled with the fire of many fresh chiles.The sauce is not plentiful, but is very strongly flavored, and clings tightly to the potato chunks and cauliflower florets.

It is one of my favorite “classic” curries, and is one that I have never made before, mainly because I could always get it in local Indian restaurants.

As that is no longer the case, here I am, book in hand, hankering for a bowl of aloo gobi and no great Indian restaurant within an hour’s drive.

What else is a woman to do but grab the cauliflower by the head and make it into a curry?

Did I use a recipe?

No. I have to admit that I did not–I just remembered what the great chef at Akbar in Maryland put in his, and followed suit. He was from Dehli, mind you–in the north, but one of the waiters told me that he had also spent time cooking in Hyderabad, in the south-central part of India, and so had picked up the southern ways with chiles, mustard oil, mustard seeds and fenugreek greens.That was what made his food so good, I think–just when you thought he was just an amazingly proficient chef in the complex court dishes of the Mogul empire, he would turn around and make a steaming platter of aloo methi–potatoes fried with fresh ginger, chiles, ground spices and bittersweet fresh fenugreek green that exploded with the flavors of southern India from the first bite.

I didn’t use a recipe for the kofta, either, to be honest. At this point, I just work instinctively with Indian spices, and only use recipes for bread or for dishes that I am not familiar with. For the kofta, I went with a basic kofta recipe, similar to my saag kofta, and changed the spices to reflect a less spicy, more sweetened flavor. I also added pomegranate molasses to the meat mixture and the sauce, in order to bring that sweet-sour fruit flavor that I wanted to highlight in honor of the Persians, who brought pomegranates to India. I also removed the turmeric and paprika that are used to color the yogurt-based sauce for the kofta; very much wanted the dish to contrast with the highly spiced brilliant yellow, hot aloo gobi.

One more note about the potatoes before I go to the recipes: most Indians would peel thier potatoes, so to be authentic, you should, too. However, I had some very pretty, very young, tender fingerling potatoes, both red and white, in the house, and those are the ones I used. I just scrubbed their baby skins until they were squeaky-clean, and cut them into sixths or quarters, and used them that way. Their waxy texture suited the dish admirably–they kept their shape and the creaminess of their flesh contrasted with the crisp-tender cauliflower. You can use whatever potato you want, but remember that the waxy ones will hold their shape and have a delightful texture. I tend to use the mealier potatoes for fried dishes like pakora or aloo methi.

After the first bite, Zak and Morganna declared that reading the history of curry was good for me and that I should do it more often.

I am sure that their enthusiasm for my reading material was not in the least bit self-serving.

Ingredients:

8 small fingerling potatoes, well scrubbed and cut into quarters or sixths, depending on size

pinch salt

1/2 head cauliflower, cut into florets about the size of the potato chunks

pinch salt

2 tablespoons mustard oil or peanut oil

1 small onion, sliced thinly

1 1/2″ cube fresh young ginger, peeled and cut into very thin slivers

2 ripe jalapenos, sliced thinly (or to taste)

1/2 teaspoon whole cumin seeds

1 teaspoon mustard seeds

salt to taste (about 1/2 teaspoon)

Masala Ingredients:

1/4 teaspoon fenugreek seeds

generous pinch asafoetida/hing powder

1/2 teaspoon turmeric

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

1 1/2 teaspoon coriander seeds

1/2 teaspoon black peppercorns

1 handful fresh cilantro leaves, roughly chopped

wedges of lime

Method:

In two separate pots of appropriate size, just cover potatoes and cauliflower with water salted with just a pinch of salt, and bring to a boil. Cook cauliflower until it just begins to soften, then drain and set aside. Cook potatoes until they are halfway soft, turn off water, but do not drain.

Grind the masala mixture into a fine powder.

While the potatos and cauliflower are parboiling, heat oil in a skillet or saute pan and add onions. Cook, stirring, until they are half-browned–a dark reddish gold color–then add the ginger and 2/3 of the chile. (Reserve the rest for garnish.) Keep cooking for another minute, add whole cumin and mustard seeds and continue cooking until the cumin seeds darken, the mustard seeds start popping, and the onions are a deep reddish brown. It will all be very, very fragrant. Add the masala powder and keep stirring, cooking until the powder toasts slightly–about one more minute.

Add the potatoes and their cooking water, and the cauliflower. Stir to combine. Bring to a brisk simmer. If there isn’t enough water, add some more to just cover all ingredients. Add salt to taste.

Allow to simmer down until there is barely any sauce, and what is there clings tightly to the potatoes and cauliflower florets.

Stir in reserved chiles and cilantro and serve with lime wedges–the shot of sour really makes the spices sparkle.

Pomegranate Kofta

To make the pomegranate kofta, follow my instructions for saag kofta, but make the following changes:

1. Leave out the collard greens altogether. Instead, remove the seeds from a medium pomegranate and set aside.

2. For the curry paste, use the following spices, and follow the directions in the recipe for saag kofta: 1/2″ cube fresh ginger, 3 cloves garlic, 1/4 teaspoon dried chile flakes, 1 teaspoon cumin seed, 1/2 teaspoon fennel seeds, 1/2 teaspoon cardamom seeds, 3 whole cloves, 1 black cardamom pod, 1/2 teaspoon black peppercorns, 1/2 teaspoon salt, 1/2 teaspoon pomegranate molasses.

3. For the sauce, follow the directions and ingredients for saag kofta, except make these changes and omissions: no paprika or turmeric, and add 1 teaspoon pomegranate molasses with the cream.

Serve with a generous handful of pomegranate seeds and minced mint leaves sprinkled over the kofta.

Dim Sum Delight: Char Siu Bao

I’ll never forget the party my in-laws hosted for me when I graduated from culinary school at Johnson & Wales.

It was a dim sum brunch at King’s Garden Restaurant in Cranston, RI that we held early in the day before the graduation ceremony, which was a gargantuan affair in downtown Providence. Most of what I remember about the day, in fact, came about at the morning party, when my parents had their first exposure to dim sum.

My mother is a notorious omnivore who will try nearly anything once, except maybe fish, which she tends to dislike.

My father has much more conservative tastes, but he has never met a fish he hasn’t liked.

However, one cuisine that he has maintained for years that he dislikes is Chinese. This is despite the fact that I have cooked him Chinese foods many times and he has eaten them and liked them. I think that his early exposure to MSG-laden chop suey and chow mein scarred him, and convinced him that there was nothing good to be had when it came to Chinese food.

I hadn’t bothered to tell him that the party was held in a Chinese restaurant; he didn’t find out until we were stuck in New York City traffic on Friday, on our way up from Maryland to Rhode Island. (For complex and irritating reasons, we ended up moving to Maryland the week before I graduated, so we had to come back for the ceremony.) Dad was complaining as we inched through Connecticut that he had never seen such miserable amounts of cars (that is what happens when you live in West Virginia–you think you know traffic until you come upon New Yorkers escaping the city on Friday)and that he was starving to death, but he didn’t dare stop for fear of never being able to get back on I 95.

My friend, Nikki, was tired of hearing him complain, and glanced at him and said, “Oh, hush, George. You’ve got the food tomorrow to look forward to.” She winked devilishly at my mother, who was holding down the back seat with Zak and I.

“Something special for brunch?” he asked idly.

She smiled brightly and said, “Uh, huh. Chinese food.”

His face sank and his mood plummetted with it.

I could hardly blame her; she hadn’t forgiven him for teasing her about her bridge phobia as we crossed the Tappan Zee, so she took every opportunity after that to needle him.

This was also to be the first time my folks had met Zak’s family en masse–and so not only did they have to contend with strange food first thing in the morning, and Nikki’s cheery ribbing, but they also got to meet the outspoken, gregarious, loud gaggle of gourmands that comprise the Kramers.

The thing is–these folks can eat. A lot. A whole lot. And they make no bones about it. When I was ordering for us, my parents were shocked at the amounts I called for from Emily, the waitress, but they were more shocked when Zak’s dad, Karl, his sister, Laura, and brother, Dan, all started suggesting across the table that I up portions of various delicacies such as coconut pudding, turnip cake and especially, steamed pork buns. (Ah, yes–you knew we had to come to the pork buns eventually, didn’t you?)

Yes, steamed pork buns. For our table of thirteen, I think we had five orders. That is fifteen buns. Or maybe we had six–eighteen buns. That is not taking into account the puddings, the sweet buns, the dumplings, the taro balls, the turnip cake, the spring rolls, the lotus leaf rice packets, the stuffed bean curd and the bowls of hot and sour and wonton soup. My parents’ eyes just kept getting bigger and bigger as the list continued. Steamed sponge cake with orange flavor. Ha gow. Chive dumplings. Every time I called out the name of a specialty to see if anyone wanted it, there was usually one or more takers. Spirited discussion ensued over the merits of this bun or that, or siu mei over ha gow, but in the end, we got nearly one of everything, two of many things and three or more of more things than I think we should admit to.

When the soup came, for the first time since we had gotten there, silence descended on the table as the Kramers took to eating.

My parents tasted the wonton soup with quizzical looks on their faces. The delicate flavor of the broth was not what they were used to, and they didn’t seem to know what to make of the cloudlike wontons enrobing tiny meatballs of pork and shrimp stuffing.

The Kramers had no such problems. They drank down their soups quickly, then resumed chattering, characteristically over where we were going to have dinner. Legal Seafood had been decided upon as a great favorite and we had reservations, but of course, we had to argue over whether or not the venerable establishment had gone downhill in recent years.

My parents stared on silently, whether in shock or amusement, I cannot say.

The first dim sum goodies began to arrive just as Emily cleared the soup dishes.

Stuffed tofu and turnip cake. Definate no-goes in my father’s universe. Even Mom wasn’t thinking any of them looked particularly good. Which was fine with Zak and Dan, because it meant more for them. These plates were soon cleaned, just in time for the flurry of dumpling steamers that began to land like a tiny fleet of invading UFO’s upon our table.

The serious eating began. Chopsticks clattered, chili oil was passed and squabbled over, and enough tea to drown an elephant was drunk. I noticed that Emily was taking care of no other table but ours, even though the restaurant was packed with parties large and small. It didn’t bother her: she was having a grand time chatting with the family, many of whom she had met before, and telling my parents how Zak and I came in for dim sum regularly at least once a week and also ate congee once or twice a week, when school was too rough for me to want to come home and cook. “We keep them well fed for you,” Emily declared as she passed my mother a plate of spring rolls.

The spring rolls were the first victory in the dim sum banquet. Leave it to something deep fried to get my parents’ approval.

My Dad almost even smiled when he bit into its crispy, paper-thin wrapper.

Mom started getting into the groove. She took up with the siu mei, noting that it tasted kind of like sausage-stuffed noodles.

Zak’s Grandpa and Grandma looked on with beaming approval–they had travelled to China many times over the years and were experts in what was good and what wasn’t. They began guiding my parents, and slowly, even Dad decided that ha gow was pretty tasty, especially with some of that chili oil and soy sauce business on it.

And then, floating down like billowy cumulous clouds, the buns appeared.

Dad looked askance at them and said, “What’s that?”

Nikki grinned and said, “These here, George are the best damned barbeque pork sammiches you’re ever gonna taste. Now hush up and eat one.”

She plonked one unceremoniously on his plate and nodded at it, waiting to watch him eat it.

Mom needed no more urging than those words. She took one, peeled off the paper and took her first bite. She closed her eyes and smiled, chewing contentedly. “It’s good,” she whispered as Emily refilled her tea. “Of course it’s good,” Emily chirped. “We Chinese, we don’t keep making the same dishes forever if they are not good.”

Dad took his up, took a bite, and nodded, the corner of his mouth quirked. “Not bad,” he allowed. “Not bad at all.”

Which meant that it was really quite good, but he didn’t want to admit that, because it would mean he liked Chinese food.

Meanwhile, the pile of buns was dwindling, and a plate with two passed in front of Dad’s nose.

In an uncharacteristic show of gluttony, he snatched one of the two and set it on his plate, an action which spoke more eloquently than words that these buns were indeed, the best damned barbeque pork sammiches he had ever eaten.

Emily saw it, grinned like the Cheshire Cat and winked at me. I had told her that my parents had not ever had dim sum, and she had said that I needn’t worry. “Everyone loves dim sum. You’ll see. And if nothing else, we can feed them pork buns until they bust. I’ve never seen anyone who doesn’t like char siu bao.”

As in many things–on this point, Emily was very right.

Chinese Steamed Buns

This recipe looks hard because it is so long, but that is because I went out of my way to describe every step carefully, so you can follow it as well as you can by watching me here today. If you can make bread, you can make steamed or baked Chinese buns. The dough is not hard to work with, but there are a few tricks which you must know to be successful. One, do not do this on a terribly humid day, because the dough must be very stiff, and if the atmosphere is extremely humid, you will be adding flour to the dough until the end of time to get the texture as stiff as it should be. Also, always flour your hand when working with this dough. Some breads you can use oiled hands to work the dough, but with this recipe, you do not want to add the extra moisture, as the dough is cooked in a moist environment. So, keep your hands floured at all times. When in doubt, add flour!

Makes 10 buns

2 tsp. active dry yeast

2 ½ tsp. sugar

1 cup and 2tbsp. warm (100-105 degrees F) water

3 ½ cups (1lb.) all purpose flour

½ tsp. sesame oil

1 tsp. double acting baking powder

flour as needed for kneading and rolling out dough

Method:

Start this recipe at least 3-4 hours ahead of serving. A double rise, or a slow rise in a chilled environment will yield a more tender crumb to the bread. In that case, start at least 6-8 hours before service, or the night before.

Proof the yeast: Add yeast and sugar to warm water, stirring to dissolve yeast. Put aside in a warm spot for ten minutes, by which time the liquid should be foamy and creamy. This indicates that the yeast is alive and has begun to metabolize the sugar. If there is no foam, either the yeast was too old and died, or the water was either too cold or warm, retarding the growth of the yeast or killing it outright. Start over until you get the foam, or you will have leaden, gummy buns!

Use a stand mixer such as a KitchenAid, to mix the dough: (If you do not have a stand mixer, you can do this by hand.) Put the flour in the bowl of the mixer, and fit the dough hook to the machine. Starting on low speed, pour the water in a steady stream, making certain to scrape every last bit of the yeast foam into the flour. Raise the speed slowly, finally allowing the machine to knead the dough into a ball that pulls away from the sides of the bowl. If the dough refuses to come together into a ball, add water by tablespoons until it does so. Scrape down the bowl as needed. Once the dough ball has formed, put machine on highest speed for about a minute to start the kneading of the dough. Stop machine.

Hand knead the dough: Flour a pastry cloth or board lightly, and dump dough into the center of flour. Flour hands and knead for at least three minutes, incorporating flour as needed to create a dry, fairly stiff dough. The dough is ready to rise when it is springy, fingertip firm (that is, it should have the texture of your fingertip, as opposed to a soft dough that is the texture of your earlobe), slightly shiny and when pressed with a fingertip, the indentation should slowly but surely spring back.

Begin the process of letting the dough rise: Pour sesame oil into a large bowl, and coat the bottom of the bowl with a thin film. Slide dough into bowl, turn once to coat with oil, cover bowl tightly with plastic wrap, and place in a warm place to rise for about 1-2 hours, or until doubled in size. Or, place it in a cool place for 3-5 hours, such as the refrigerator, for a slower rise and a finer texture to the finished bread. Make certain that the area for rising is draft free.

While dough rises, cut ten three inch squares of wax paper and grease one side with lard or vegetable shortening. Set aside.

After dough is doubled punch it down into a flat pancake shape. At this point, you may recover it and allow it to rise again. A double rising makes the final crumb of the buns finer and lighter. After it rises a second time, punch it down into a flat pancake shape and proceed as follows:

Add a second leavening agent: Lay the dough onto a floured cloth or board. Sprinkle double-acting baking powder over the surface of the dough. Make certain it is sprinkled on as evenly as possible. With floured hands, knead the dough again, mixing in the baking powder evenly. This little secret I learned from a dim sum chef who worked for years in Hong Kong. Many recipes, he says, do not add the baking powder, but he told me that it adds extra lightness and lift and always made his buns like clouds. He is right–but you absolutely must use double acting baking powder for it to work. Single acting will not do the trick.

Knead again: As you knead, add enough flour to bring the dough back to the fingertip level of firmness. Condensation from the yeast organism’s respiration will make the dough a bit more moist and soft at this point.

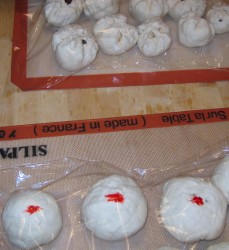

Portion the dough evenly: When the dough is back to fingertip firmness, cut dough into two equal portions, and roll each into long ropes. Cut each rope into five pieces, and form each piece into a ball. Cover dough that you are not working immediately with a towel as you go to keep it warm and from drying out.

Begin shaping the rolls: Flatten each ball into a disk. With floured hands, press the disk so it is fatter in the middle and thinner at the edges. Hold your left hand as if you were holding a drinking glass, and set the disk on top as if it were covering the glass. Push the fatter center bit of the dough down into your hand, creating a little cup or well in the dough. Place a bit of filling into the well, and quickly pleat the dough with your right hand, around the filling. If the dough is completely stiff, it should hold quite well. After pleating the dough, twist the top, and pull off the excess bit of topknot. Set the dough down on the waxed paper square, seam side up or down, depending on the finished look you want for your bun. For pork buns, I put the bun down seam side up, so that it makes an “opening flower†kind of effect as it rises and steams. For the mushroom or sweet paste filled buns, I put the dough seam side down to make a smooth top.

Let dough rise one more time: Cover with a dry towel, and allow to commence the final rising, which should take 30-60 minutes. The buns should be springy to the touch and slightly bigger than before.

Steam the buns: Bring water to a rapid boil in a pot big enough for your bamboo steamers to fit over. Put buns in steamer, not touching, if possible. Cover with lid and place steamers over the water, reducing heat to medium high. Steam for 15 minutes, then turn off heat, allowing steam to subside gradually for 5 minutes. Slowly lift the lid. If you lift the lid quickly, or worse, take the steamer off the steam suddenly, your buns may fall and wrinkle, looking quite unhappy when cold air hits them in a rush. They are ready to be served at this point, but can be held on low heat for an hour. Or, they can be cooled, sealed in an airtight container and refrigerated for up to two days and reheated by steaming again for fifteen minutes, following the procedure for opening the steamer once more.

Filling for Cantonese Char Siu Bai

The reason the recipe stipulates that you leave the filling uncovered after it is made, is because you want as much excess moisture to evaporate as possible before assembling the buns. Excessive moisture can make the buns gummy on the inside, so you want the filling to be completely cool, and dry with a thick, somewhat sticky sauce that clings to the meat.

Ingredients:

2 tsp. oyster sauce

¾ tsp. dark soy sauce

2 tsp. ketchup

1 ½ tsp. sugar

1 tbsp. Shao Hsing wine

½ tsp. toasted sesame oil

2 tsp. peanut oil.

1 small onion, diced finely

1 tsp. fresh ginger, minced

1 clove garlic, minced

1/3 pound Chinese roast pork, diced small

Method:

Combine first six ingredients and set aside.

Heat peanut oil in a wok and add onion. Stir fry until browned, then add ginger and garlic. Stir fry for one more minute.

Add roast pork and stir fry for about two minutes.

Add sauce ingredients, allow to thicken and reduce somewhat; cook for about one minute.

Remove from heat; place into a bowl and cool, uncovered in the refrigerator for four hours, or cover loosely and leave in the refrigerator overnight before using to fill buns.

A Cantonese Kitchen Classic: Char Siu

Char siu–Cantonese style roast pork–is a classic staple of the southern Chinese kitchen.

But it is a staple that is not often made at home.

Most Chinese home kitchens lacked (and as I understand it, still lack) an oven because ovens require a great deal of fuel to heat properly. So, instead of everyone in a village having an oven, there would be one family who operated an oven, and they specialized in cooking and selling roasted meats: primarily pork and duck.

While most Chinese-American families have ovens, if you go to any North American city where there is a Chinatown, you will notice small shops with whole, red-glazed, deliciously browned ducks hanging from hooks in the windows, alongside brilliantly-hued slabs and strips of crispy-browned char siu. In San Francisco’s Chinatown (a veritable paradise on earth, as far as Zak andI were concerned, especially when it came to food) it seemed as if there was a little roast shop around every corner, or down the twisting alleyways, and in my memory, the enticing fragrance of spiced, glazed meats wafted over every inch of Chinatown.

Even US cities that lack a Chinatown often have one or two restaurants, Chinese groceries or small take out shops that carry roasted meats. Columbus has both CAM–Columbus Asian Market, and Hometown Oriental Gourmet Food, both in the same strip-mall area on Bethel Road. When we lived in Pataskala, which is but a forty minute drive from downtown Columbus, we used to stop in at Hometown Oriental Gourmet Food, visit with the gregarious owners, and sit down to Zak’s favorite meal: roast pork noodle soup, which is good ramen noodles topped with meaty slices of char siu and graceful green tendrils of choy sum, then drowned in liquid gold: rich homemade chicken-pork broth. Actually, Zak usually got the soup, and I got either Singapore rice noodles or king du noodles, which was their take on ja ziang mein. He never finished the broth, so I always got the last cup or so of it: redolent of chicken and pork neck bones, slightly sweet from the char siu’s glaze, and speckled with the house-made chili oil Zak always added to it.

Heaven in a bowl.

We always stopped in there before we headed across the parking lot to CAM, because going to a big Asian supermarket hungry is a bad proposition for the wallet, besides being an exercise in frustration. Before we paid the bill, though, Peter or one of his sisters would ask if we wanted some char siu to take home, and we usually had a pound or two wrapped, and we would stow it in our freezer, in half-pound portions. That way, if I wanted a quick supper, I could thaw out a package, slice it thinly against the grain, and stir fry it with some choi sum, baby bok choy or gai lan. If any was left over, I could cut it more finely and put it into fried rice the next day, with fresh greens, some carrots and maybe some water chestnuts, if CAM had them fresh.

Or, if it was a special holiday, like a birthday or New Year’s, I could make char siu bao–steamed roast pork buns–a perennial favorite among our family and friends.

However, now that we are in Athens, we are not so lucky.

There is no roast pork to be had here.

I suppose that I could ask around at some of the Chinese restaurants and see if they would sell me some, and in truth, they probably would, but I don’t always think about it before I want it.

Which means that I just have to haul off and make it myself.

And, wonder of wonders, while it isn’t any more convenient to do so, the results are quite good, and in many ways, even tastier than what I was getting in Columbus, probably because of the quality of the pork I start out with.

Traditionally, the meat for char siu has to be fairly fatty, because the meat is cut in fairly small hunks or strips (when I say fairly small, I am not talking bite sized–what I mean is that you will not see whole butt or shoulder portions roasting for char siu ) that are hung from hooks so that the very hot air from the oven can touch every part of the meat, crisping the outside and caramelizing the sugary marinade. It is basted several times, allowing a crunchy coating to build up as it cooks, mingling with the ample fat that melts, keeping the meat moist during this very dry cooking method. Leaner cuts of pork would simply shrivel up into unappealing chunks of honey-dipped shoe leather.

For my char sui, I always use pork shoulder from Bluescreek’s organically raised, free range Yorkshire hogs. They have a slightly sweeter flavor than the stronger flavored Durocs that are raised here in Athens–those I prefer for making Mexican carnitas, or for use in posole, chili or pot roasts and stews where there will be plenty of moisture, and bolder spices and flavorings. The pork from Bluescreek, however, is very finely grained, firm, and delicately flavored, with plenty of fat, which makes it perfect for most Asian cooking applications, particularly when it comes to anything Cantonese.

In the past, I have rigged up my oven with a rack placed up high and used “S” hooks from the hardware store to hang meat from holes skewered in the edges, with pan down below to catch drippings, in order to recreate the way in which char siu is cooked in commercial Chinese establishments. And the results are fantastic, but the trouble is only worth it if one is doing a large amount of meat at a time. Which is an admirable way to go about it–make up three to five pounds of it, portion it out and then freeze it for use later.

However, I wasn’t about to go through that riagmarole this weekend just so I could make ten steamed pork buns for Morganna’s birthday party. Instead, I utilized my quick and dirty method to make char siu that ended up with just as tasty a product in a smaller amount, with a lot less trouble.

It involves putting the meat on a roasting rack in a shallow pan or on a rimmed cookie sheet, and roasting it that way. The underside doesn’t get as crispy as it does when it hangs, but it still gets quite caramelized and flavorful, and the result, once it is tucked into a puffy, cloud-like steamed bun with a bit of sauce, is just as wonderful as pork done the traditional way. I also discovered that it turns out really nice pork for lo mein, which is a great quick supper for the first weeknight after a weekend of frenzied kitchen activity.

All you have to do is make the marinade, let the meat steep in it overnight, roast it in a hot oven, and then let it cool before cutting into it. If you cut it up while it is still hot, all of that juicy goodness that the extra fat imparts is lost, and then you end up with sawdust meat coated with sugar, which is not very appetizing, especially after you went to the trouble of cooking it.

One final note: you have no doubt seen that my roast pork is not red on the outside. Traditionally, the red coloring came from the use of saltpeter–sodium nitrate–which preserves the meat and keeps the reddish color of it. (Nitrates are what keep bacon red. Without them, the meat turns an ugly grey color–which is still good to eat, mind you–it is just not appealing.) Most places that make char sui now use red food dye in their marinades to give the meat its characteristic cerise hue, which connotes good fortune and luck. I choose to not use the dye myself, preferring to let the meat take on a more natural golden brown color that I find to be just as appealing and a lot less worrisome than some sort of artificial food coloring. If you want the red color, add liquid food coloring until the marinade is the color you would like–because of the dark ingredients in the marinade, it takes a good bit of the red dye to color it properly, which is why I don’t use it.

Even without the coloring, the marinade is so flavorful and good, I don’t miss the color at all.

The inspriation for this marinade and method came from Eileen Yin-Fei Lo and Barbara Tropp’s recipes; as is usual, I tweaked it here and there, and added more of this and less of that, until it suited me, so now it is a bit different than either of the original recipes it came from.

Char Siu

Ingredients:

2 ¼ pounds moderately fatty pork shoulder or butt

1 ½ tbsp. dark soy sauce

1 ½ tbsp. light soy sauce

1 ½ tbsp. honey

1 ½ tbsp. oyster sauce

2 tbsp. shao Hsing wine

3 ½ tbsp. hoisin sauce

½ tsp. five spice powder (I like Penzey’s brand)

black pepper to taste

red food coloring (optional)

Method:

Cut meat into strips 1 inch thick and seven inches long. Using a fork, tenderize meat by piercing all over. This also allows the sauce to penetrate.

Mix marinade ingredients into a ziplock bag large enough to hold meat.

Place meat in bag, mush it all around in the marinade so it is all covered, then push out all of the air, seal bag and leave it in the refrigerator for several hours, overnight or for twenty four hours.

Preheat oven to 450 degrees. Place roasting rack on rimmed cookie sheet, and drape meat over it. Roast for 20 minutes, until the meat is done. Baste the meat as it cooks a couple of times with some of the marinade. Allow to cool after it is done, then cover and refrigerate until needed.

Lunar New Year Birthday Party

It was supposed to rain buckets all day.

Instead, the weather was mostly balmy, though sometimes grey and damp.

We didn’t have firecrackers, but we did have a plethora of red balloons that Morganna and her friends popped after the party, in order to scare away the evil spirits.

There was lucky money, and the entire house was festooned in red tissue paper and ribbons, and green crepe (to bring money in the coming year) with balloons and a centerpierec of golden citrus fruit piled high next to a ceramic fu dog, many maneki neko to beckon in luck, and a crockery filled with chopsticks for the guests to use.

And then, there was the food: we started with siu mei–steamed pork buns shaped like purses, then scallion pancakes, pan-fried to a crispy finish. Thinly sliced turnip cake came next, creamy white inside and pan-fried to a delicate golden lace on the outside. Then, spring rolls filled with sweet bamboo shoots, slivers of pork, Chinese sausage-lop cheong-shrimp, black mushrooms and garlic chives, then deep fried to resemble gold ingots. Then came three batches of steamed buns: first the sweet red bean paste filled ones, then the mushroom filled ones of my own devising which take the place of char sui bai for vegetarians and Muslims, and finally the pork filled Cantonese classic.

I forgot to take pictures of most of this bounty, as I was in the kitchen, pretty much chained to the stove, constantly battling oil spills, recalcitrent dough and steamers trying to fall into their water baths, but at least my Mom dragged Morganna from her friends and me from my kitchen successfully to get a picture of the three of us.

There is a glimpse of all the fun, and food, the festoons and frolic. Morganna dressed as her Uncle Briyan said, “in girl clothes,” which is not a usual sight for us, and laughing joyfully, a sight which is becoming more and more prevalent, thankfully. Behind her is my mother and I; you can see through the laughter and proud beaming smile, and the shy quirked mouth that each of us exhibet, that none of us is fond of being photographed. It isn’t very well posed, but it is true to our personalities.

It was a fun time, even if I did cook for two days straight and had houseguests (very welcome and beloved ones at that) the entire time. Our friends and family pitched in to make the party go–Mom stayed in the kitchen and helped me, while Uncle Bryian, armed with his bagua compass, occupied the kids with decorating the inside and outside of the house in the colors red and green–red for fortune, joy and luck, and green for money, growth and abundance (and because we had run out of red). Brother Thomas, bless him, arranged the fruits and flowers, and Morganna’s gifts, placed the napkins and plates just so and set up the tea station, and took some photographs. (We drank puer tea all day–which Mom had never had. She swears she hates tea, but she sure did like this stuff. I think I may gift her with some, as she has only had Lipton before, and so knew no better.)

After all of the dim sum was consumed, and our friends, family and guests were becalmed a bit, I had Tom bring me the centerpiece of citrus he had so carefully arranged, and cut each fruit into wedges, then piled them onto a sky-blue platter. Blood oranges, navel oranges, and pomelo made a beautiful bed for a scattering of golden slices of crystallized ginger–they looked like sparkling gold coins dropped over a platter of precious gems.

Most importantly, they tasted divine, like kisses of the summer sunlight that yet remains elusive, but which, like fortune, joy, and luck, we entice into our year by eating its proxy and sharing its sweetness.

Weekend Cat Blogging: The Birthday Girl and Cat

Today, we have much to do. The house needs some more cleaning (though we did a good bit of that yesterday) and I have doughs to make and fillings and sauces to assemble and create, and presents to wrap.

Tomorrow is Morganna’s birthday, in addition to being the first day of the Lunar New Year celebration.

She wanted a dim sum feast for her birthday, and in lieu of birthday cake, she wanted scallion pancakes and sweet bean paste buns.

So…that is what I am making.

I think around twenty people are invited to show up; I have to go send email out and think of a parking strategy.

Pictures of the food and festivities tomorrow will be forthcoming.

Wish us luck!

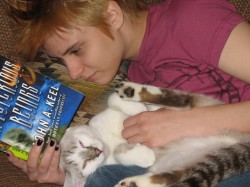

Our picture today features Morganna, on the couch reading, with her cat, Lennier cuddling in a most undignified fashion.

For more weekend cat blogging, check out Boo at Masak-Masak.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.