Eating Together

Reading about the benefits that accrue to children who eat often with their families gladdens my heart, amuses me and saddens me all at the same time.

Reading about the benefits that accrue to children who eat often with their families gladdens my heart, amuses me and saddens me all at the same time.

It makes me happy to know that there are researchers working in the fields of nutrition, child psychology and sociology who are willing and able to do design studies that confirm what many parents have suspected all along: that meals do not just fuel a child’s body, but sustains their minds and souls as well. This is also true for adults, of course, not just kids; food has never just been about calories and nutrients, but has always been part of the social fabric that holds people together in good times and in bad.

It pleases me to see that there are those who feel that research in this area is important enough to pursue and publish; and I am given heart every time I see mention of these studies in major media outlets.

I am amused, of course, because when I read these news snippets, I always say to myself, “Well, gee, duh–I could have -told- you that.”

Partly this comes about because the idea of eating together is one of those elusive “traditional family values” which supposedly Americans have left behind in a rush toward individual personal satisfaction, longer workdays and decadent lifestyles. It know there are some Americans who are so selfish that they pursue their own desires to the detriment of their children, just as there are workaholics out there who would rather work overtime than spend time with their families. As for those decadent lifestyles: the most dedicated partiers I have known have not had children because thankfully, they have known that it would really put a damper on thier chosen way of interacting with the world.

There are exceptions, of course, but I think that nearly everyone in the United States holds the ideal in their hearts that families should sit down and eat at least one meal a day together. And why not–we have been essentially programmed to see family meals as a social norm. Television sitcoms and series films alike show families around the table; it is a situation that is rich with both comedic and emotionally tense possibilities. (This isn’t just an American phenomina; one of my favorite films of all time is Ang Lee’s “Eat, Drink, Man, Woman–” a film which focuses on the interactions of one Taiwanese family around the Sunday family feast.) Our holidays, particularly Thanksgiving, Christmas and Easter, center around large family dinners, and everywhere in our culture, from holiday cards to advertisements, we see images of happy families sitting around the table sharing copious amounts of food.

But when I read these news stories on the benefits of family meals, I am also saddened by the statistics that show how many families are not eating together. Depending on which set of numbers one choses to believe, roughly half (48%) or two-thirds (66.6%) of American families do not partake in regular family meals. That is a lot of people who do not have the time or do not take it, to eat together as a family.

I am not going to start on a rant here about how the United States is going to go to hell in a handbasket because low income families with two parents working twelve hours a day in order to afford to buy thier kids shoes and food don’t take the time to eat with their kids. In fact, I cut a lot of lower income families a lot more slack than I do those who are solidly middle class to upper class. Is that classist of me? I suppose an argument could be made that it is, however, I prefer to see it as me having a realistic idea of what it means to be poor.

I am not going to berate people who are doing their best to make ends meet and try to guilt them into eating with thier kids. Most of them would like to eat together as a family, but because Mom and/or Dad (many of these households involve a single parent) are working their butts off most of the time, they can’t, and they probably feel pretty guilty about it already.

As for those households where there is plenty of money and the reason that the family seldom get together to eat is that the kids all have a bazillion extracurricular activities and Mom and Dad have their own activities: I am not going to guilt them, either.

I just have this to say: slow down. Let your kids be kids and stop micromanaging every second of their lives. Let them have some free time to just lay around dreaming or run around like little screaming maniacs in the yard in unconstructed play. Please? I am not against soccer or ballet lessons or horseback riding or art classes; on the contrary–I’d have liked to have had some or all of those when I was a kid, too. (I did have the horseback riding, and it was great fun.) But does one kid have to do all of them to be a good, well-rounded kid? And if you multiply those lessons, sports and activities by several kids–it is no wonder Mom and Dad don’t think that there is time to sit down and have dinner more than once a week.

Again–slow down. Spend time with the kids: parents are more than shuttle services to and from activities. They are the primary role models kids have for acceptable adult behavior, and that is more important than cramming a kid’s life with every educational opportunity that money can buy.

Educational opportunities bloom around children and in a household, and kids learn by watching and doing what their parents do. If they see parents primarily as a means to an end–that is how they will treat them (and that’s how they will treat others, as well.) If they see parents as involved, caring and fully present in the moment–they will learn to be that way, too. Eating with kids gives them a chance to learn table manners, how to converse on matters great and small, how to interact with peers and non-peers, how to laugh and how to enjoy food. Parents can become great arbiters of taste; what parents eat, kids are likely to eat as well, though with some children, it may take exposure to a strange food ten or fifteen times before they try it.

Cooking with kids gives them a chance to learn not only a useful life skill (how to feed oneself and others is a skill which never becomes unstylish–a good cook always has many friends), but also to learn scientific and mathematical principles. A parent can make math real by teaching a kid how to scale a recipe up or down while keeping the ratio and proportions between the ingredients the same. Conductivity can be explained while setting a pot on the stove to boil. Showing how baking powder makes muffins rise gives a practical knowledge of chemistry. Cutting apart a chicken gives an anatomy lesson.

Even more important than manners, communication skills, science and math, however, are the spiritual lessons that the family table can give.

Eating together is a spiritual act: not only on holidays or feast days, but every day.

When we sit down together to break bread, to eat, we are sharing not only food, conversation and drink, but we are creating an emotional bond with those seated around the table. We are sharing love, peace, friendship and kinship. We are giving of each other, to each other. We are saying, “you are important,” to each other, and as we take in physical nourishment from the food, we also absorb emotional energy from each other.

I know this sounds mystical, and maybe a little “woo-woo-out-there.” But, it is true.

Think about the times people have eaten together and had an argument at the dinner table. Was the food enjoyable? Can you even remember what it tasted like? Did the flavor of the food change as the emotions churned around the diners? How did your stomach feel as you ate a meal while surrounded by discord, tension and anger?

You most likely didn’t feel very good, and if the food started out tasting good, it probably turned to ash in your mouth. I know the few times angry words flew around the dinner table when I was a kid, the food lost its savor, and I could no longer eat.

But when there is fellowship, love and laughter around the table, the food cannot help but taste divine, and when we gather as families in this way, we give gifts beyond words to our children.

I suppose that is why I am always feeding people. I grew up with lots of family meals; I ate at home every night with Mom and Dad, and if not at home, then generally with Gram and Pappa or Grandma and Grandpa. On the weekends, we often went to Aunt Nancy’s and there are many memorable meals that Aunt Judy or Aunt Sis cooked for us. In fact, one of the main things my family did when they got together numbers large or small, was eat, together, in a spirit of sharing and love.

Even when things were tense in my teen years, mealtimes were most often pleasant. I can only remember one or two meals where there was an argument; our family tended to make certain that disagreement stayed out of the kitchen and dining room at mealtimes. There was always time before and after a meal to squabble–the table was for eating and sharing.

I remember that my friends came over to eat a lot, but I never went to their houses to eat, because they didn’t have family meals. So, Mom and Dad had them over and we shared with them; in later years, as we grew up, my friends realized what had been shared with them, and they thanked Mom, because for some of them, those dinners were some of the only “normal” family interactions that they had.

Now my own daughter lives with me, and we eat together every night, and most often we have breakfast together, too, before she goes to school, even if it is only a bagel and cream cheese or toast and coffee. On weekends, she helps me cook more elaborate breakfasts: steel cut oats with fried apples, cranberries and raisins, blueberry pancakes with bacon, waffles scented with vanilla beans and fruit, or German pancakes drizzled with lemon juice and dusted with powdered sugar.

She revels in the weekend dinners when family and friends gather, and she takes great pride in helping me cook for them. As she has grown stronger and more confident in the kitchen, she has taken over more tasks; she can handle the large Cantonese iron wok now, without hurting her wrists, and she can cook a mean chicken with fermented black beans and bitter melon.

Food, cooking and sharing have become a thread that binds our family together. It is a tradition that I have taken from my own childhood and have gratefully passed it down to my daughter. When we cook together and share meals, I can tell her about her great grandmothers, one of whom she never met, and pass down their memory as we slice onions and string beans.

More than anything, these memories are sacred. They weave the past into the future in a way that is as real and tangible as the food we share.

I am proud to give them to my daughter, and hope that in other homes, in other kitchens, around other tables, similar threads are being spun and woven into the fabric of people’s lives.

–

Food News Flash

Paul Prudhomme to Return to New Orleans

According to the New York Times, this Friday, Chef Paul Prudhomme plans to lead a caravan of trucks from Alabama to his offices in Elmwood, Louisinana, where he intends to cook (in the parking lot, if he has to) for “anyone who needs it.”

“We’ve got generators, food and trailers, and we’ll cook for anyone who needs it,” he said, adding with a shout, “We’re going home, baby!”

In addition, The Council of Independant Restaurants of America, has set up a job bank for displaced workers at their website.

In the Miami Herald, a food writer muses on the fate of New Orleans’ food culture.

Meanwhile, Americans are warned that food prices are likely to rise as a consequence of the hurricane damage. The Washington Post reports that coffee, bananas, chicken and seafood prices are bound to rise in the coming weeks, citing transportation difficulties, fuel prices and lack of water and electricity in slaughterhouses and farm buildings as the root causes.

In Praise of Pressure

Not many people enjoy pressure, though I would say that plenty of folks work better under pressure than others. In fact, I would say that I am one of those people; I tend to do my best writing when under deadline pressure, and some of my best cooking is done when there is a time limit involved in the exercise.

Not many people enjoy pressure, though I would say that plenty of folks work better under pressure than others. In fact, I would say that I am one of those people; I tend to do my best writing when under deadline pressure, and some of my best cooking is done when there is a time limit involved in the exercise.

I actually think that a lot of busy people who cook could do with a bit more pressure in their kitchens. I bet every harried twenty-first century reader who struggles to juggle job, family and homelife probably has decided that I am off my nut to say so, but I am not talking about the kind of pressure that makes a person run around in circles hooting like Daffy Duck and pulling at her hair.

I am talking about the kind of pressure that gives you time, rather than taking it away.

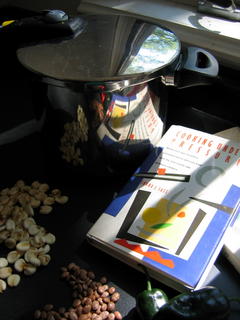

I am talking about a pressure cooker.

Oh! The lightbulb flashes and realization dawns! I am not advocating the ideal of driving oneself mad with over-work. I am promoting a kitchen tool that really does help make life easier, and gives folks who really don’t have all day to spend in the kitchen a way to make all of those homey, happy long-cooked comfort foods like stews, braises, curries, soups, chilis and mashed potatoes in less time than it takes to order a delivery pizza. (Depending on how fast your pizza people are. Mine here in Athens can be slower than molasses in January.)

Imagine this: boiling potatoes in about eight minutes or so, resulting in mashed potatoes in ten minutes. Or collard greens that take all of fifteen minutes to prep and cook. Or a pot roast in forty-five minutes. Or a stew in fifteen.

Imagine this: boiling potatoes in about eight minutes or so, resulting in mashed potatoes in ten minutes. Or collard greens that take all of fifteen minutes to prep and cook. Or a pot roast in forty-five minutes. Or a stew in fifteen.

Or a pot of savory pinto beans in ten minutes, ready to be mashed and fried with onions and garlic, or to be turned into soup beans.

Just about anything that takes all day to cook can be cooked in less than an hour with a pressure cooker. Imagine that. Less than an hour. And it tastes long cooked, too. Often, in fact, meats are more meltingly tender and moist coming out of a pressure cooker than they are if they are braised or stewed using classical methods, because the extra pressure involved dissolves the fat and gelatins in the connective tissue even more efficiently than simply simmering the meat does.

They work very simply: liquid is brought to a boil in the cooker, along with whatever food items are to be cooked therein. The cook puts the lid on the cooker, which has a gasket in it to seal it completely, locks it down in several ways, then brings the cooker up to full pressure–usually around 15 psi. Then the heat is turned down to low, and the food is left to cook for the necessary amount of time until it is done. Then, pressure can be released in two ways.

The quick release method, which is best used for vegetables and some meats, but never beef, is to simply open the pressure valve and let the steam out. Flick a button, (make sure the steam valve is pointed away from you and anyone you love) and in a great hiss, the steam comes jetting out. (If there are any cats under my feet when I perform this operation, they teleport themselves instantly elsewhere, because the sound of steam escaping the little vent is apparently the same sound as the Great God of Cats hissing His displeasure.) The other way to release the pressure is called the “natural release,” which takes fifteen to twenty minutes. Basically, all you do is put the cooker off heat and let it cool down on its own. This is the method to use with beef; if you use the quick release method on beef, its will toughen because of the quick temperature and pressure inversion. (This isn’t a problem with other kinds of meat, though I tend to let the pressure on lamb, venison or bison drop naturally, too.)

I know, I know. Everyone is scared of pressure cookers, and everyone knows a story about somebody’s neighbor’s Aunt Tillie who was making spaghetti sauce in her pressure cooker and it exploded, sending a geyser of boiling steam and scarlet napalm lava all over the kitchen ceiling where it showered down and gave cousin Bubba third degree burns and killed the Avery the cat with shrapnel.

Well, I am here to put the Aunt Tillie myth to rest along with Avery the cat (God rest his feline soul). The modern pressure cookers have a whole passel of safety measures built into them to keep the geyser and shrapnel scenario from occuring. The new pressure valves have failsafe devices built into them; in some brands, if the vent is clogged and the pressure rises above safe limits, there is a second pressure valve that will open to release the steam that builds the pressure. In other brands, a failsafe valve opens because a metal alloy that will melt at the precise temperature and pressure of a cooker about to go into the danger zone melts, opening the valve. The downside of one of those cookers is that you then have to replace the pressure valve.

My favorite brands are the Fagor and Kuhn Rikon, though I find the latter to be unreasonably pricey. My current cooker is a Fagor, and I am quite happy with it, and have been using it to death for the past several years with no problem.

Cooking with a pressure cooker requires some finesse and practice, however. (At this point, some readers are probably thinking, “Well, why not use a crockpot–you just throw stuff in and walk away. Well, no you don’t, not if you want good food to come out of it, anyway–there is finesse involved in crockpot cooking, too.) Mixed stews, in particular, require some forethought and planning; different ingredients cook at different times in the pressure cooker, so you may have to cook in stages.

Cooking with a pressure cooker requires some finesse and practice, however. (At this point, some readers are probably thinking, “Well, why not use a crockpot–you just throw stuff in and walk away. Well, no you don’t, not if you want good food to come out of it, anyway–there is finesse involved in crockpot cooking, too.) Mixed stews, in particular, require some forethought and planning; different ingredients cook at different times in the pressure cooker, so you may have to cook in stages.

Take, for example, posole.

Posole, for those who do not know, is a form of corn that has been treated with lime (the mineral, not the fruit) so that its hull can be removed. Then, the hull is washed away. At this point, the posole can be cooked up nice and pretty, ground up into fresh masa dough, or dried again, so that it can be stored and cooked another day. This is a Native American staple food of the desert Southwestern US and northern Mexico.

Southerners may be more familiar with it as hominy. Hominy is made the same way, though I suspect the corn varieites are slightly different. Hominy can be ground up into grits–the quintessential Southern comfort food, or it can be cooked whole, and it is often canned, and in a pinch, one can use canned hominy to make posole stew, but I think that the texture and flavor of the dried corn product is much superior.

Anyway, dried posole takes a long time to cook. You are supposed to soak it overnight (or you can use the quick-soak method–bring a half pound of it to a boil in three cups of water, boil it for three minutes and then set aside to soak off heat, covered for an hour), and then cook it for a couple of hours until it is tender. Well, I don’t always remember to soak it overnight, and I don’t always want to sit around and nursemade a pot on the stove for several hours, nor do I think far enough ahead to use the crock pot, so, I turn to my pressure cooker, which cranks out perfectly cooked posole in forty-five minutes every time.

But, seldom do I make just posole. I like to make posole stew with pork and pinto beans. (I am told that the pork was brought by the Spaniards, and the pinto beans are a Sonoran variant. And here I thought the beans were my own hillbilly innovation.)

But, unsoaked pinto beans take fifteen minutes to cook, and cubes of pork shoulder or butt take about eight to twelve minutes to cook. What to do?

Well, it is simple enough. Saute some of the onions, garlic and chiles (Barbara’s Hillbilly Holy Trinity) in some bacon grease or olive oil until the onions brown, then throw in your posole and a good bit of chicken broth. Bring to a boil, slap the lid on, and bring up to pressure, then turn it down and let it cook for thirty minutes while you prepare the pork.

To prepare the pork, take your other half of the Holy Trinity, get those onions about halfway to brown, and then dump in the pork that you have dredged in seasoned flour and brown it all up nice and and lovely. Add some herbs. When the onions are caramelized and the meat has a nice, reddish brown crust on it, use some beer to deglaze the frying pan, and then reduce the beer. Scrape everything from that frying pan into a bowl, or heck, just leave it in the pan, covered, off heat, to wait.

To prepare the pork, take your other half of the Holy Trinity, get those onions about halfway to brown, and then dump in the pork that you have dredged in seasoned flour and brown it all up nice and and lovely. Add some herbs. When the onions are caramelized and the meat has a nice, reddish brown crust on it, use some beer to deglaze the frying pan, and then reduce the beer. Scrape everything from that frying pan into a bowl, or heck, just leave it in the pan, covered, off heat, to wait.

At that point, the timer goes off, you quick release the pressure, add the beans, bring to a boil, put the lid on and bring back up to pressure and cook for seven minutes. Quick release the pressure and then throw in the pork, and the tomatillos, and bring back up to pressure, and cook for about eight to twelve minutes.

It is all a matter of timing. You end up with a savory stew in about forty-five minutes, and it tastes really, really good, especially if you have sweet, ripe tomatillos to add to it. If you don’t have tomatillos, you can add fresh tomatoes (I bet those really fresh cherry tomatoes would be perfect), but I like the tomatillos better, because they add a honey sweetness along with a bit of a tang to the dish.

It is all a matter of timing. You end up with a savory stew in about forty-five minutes, and it tastes really, really good, especially if you have sweet, ripe tomatillos to add to it. If you don’t have tomatillos, you can add fresh tomatoes (I bet those really fresh cherry tomatoes would be perfect), but I like the tomatillos better, because they add a honey sweetness along with a bit of a tang to the dish.

And while the final cooking is going on, you just slice up some scallion tops and fresh chiles, and roughly chop some cilantro for a garnish. If you want, you can grate up some queso blanco or jack cheese, too. A bit of cheese never hurt anyone. And if you want the broth to be thicker, just cook up a tablespoon of oil with a tablespoon of flour until it is smooth and bubbly, and add it to the boiling stew.

And that is it. Simple, almost sinfully so, and fast, but it tastes like you cooked it all day.

Pressure Cooker Posole and Pork Stew

Pressure Cooker Posole and Pork Stew

Ingredients:

1/2 pound dried posole, rinsed, soaked overnight

2 large onions, sliced thinly

3-5 ripe serrano chiles, sliced thinly

1 poblano chile, finely diced

6 cloves garlic, sliced thinly

1 tablespoon bacon grease or olive oil

2 teaspoons adobo seasoning

1 teaspoon smoked Spanish paprika

1 pinch Mexican oregano

1 1/2 quarts chicken broth or vegetable broth

1 pound boned cubed pork butt or shoulder

2 tablespoons flour seasoned with salt, pepper, adobo and smoked paprika

1 1/2 tablespoons bacon grease or olive oil

6 ounces of lager beer (drink the rest yourself, or save it for something else, or rinse your hair with it–it makes it shiny)

1 cup pinto beans, rinsed and soaked or unsoaked

1 pint fresh, preferably really ripe tomatillos

3 scallion tops, thinly sliced

1 ripe serrano chile, thinly sliced

1 handful cilantro leaves, rinsed and roughly chopped

handful of grated cheese (optional)

Method:

Drain the posole, rinse and drain again.

Divide your Holy Trinity ingredients into halves, setting one set of them aside.

In pressure cooker, melt bacon fat or heat olive oil on high heat. Add onions and chiles, and saute until onions turn medium brown. Add garlic, and cook until onions caramelize. Add seasonings, chicken broth and posole. Bring to a boil, put the lid on, lock it down and bring up to full pressure. When full pressure is achieved, turn down heat and set timer for thirty minutes.

In a frying or saute pan on high heat, heat bacon grease or olive oil, then cook onions and chile until onions are golden brown, then add garlic. Lower heat slightly and continue cooking. Dredge pork in seasoned flour, and when the onions are medium brown, turn heat back up, and add meat to pan. Allow meat to brown, stirring frequently, until onions are a mahogany color and the meat has a reddish crust on it.

Deglaze the pan with beer, and cook down until liquid reduces to a thick syrup. Turn off heat and set aside.

When timer goes off, quick release the pressure and open the cooker. Add drained and rinsed beans, and bring to a boil, lock lid in place and bring to full pressure. Turn down heat to low and set timer for eight minutes.

While beans are cooking, take the papery outer covering of the tomatillos off and rinse the fruits. Cut them all into halves if they are small, quarters if they are large.

When timer goes off, quick release the pressure, put pork and all juices from the pan in, dump in the tomatillos, bring to a boil, lock lid down, and bring to full pressure again. Turn down heat, set the timer for about eight minutes, and allow to cook. When timer goes off, quick release pressure and open cooker. Test all ingredients–the meat should be fork tender, the beans should be tender (blow on one in a spoon–if the skin splits under your breath, it is done) and the corn should be tender-chewy. If everything is done to your satisfaction, then great, you are done (unless you want to thicken the broth.) If something still needs cooking, bring it to a boil, lock down the lid, and bring up to pressure and cook about five minutes more. Repeat as necessary. (As you gain experience using a pressure cooker, you will begin to have a better feel for how long things take to cook.)

To thicken the stew, in the frying pan, melt one tablespoon of bacon grease or heat olive oil on high heat. Add one tablespoon of flour (use up what is left from dredging the meat) and stir into the hot fat. Cook, stirring, until thick and bubbly, then add to the boiling stew, and stir until thickened.

Top with garnishes and serve.

Notes:

If you want your posole to “bloom,” that is, if you want the endosperm to explode into flower-shaped balls as it cooks, you must remove the pointed tip cap from the seed after it has soaked. If you leave it intact, the corn kernel will stay in its shape even as it cooks fully. I am too lazy to remove the tip caps, so my posole never looks like “underwater popcorn,” as I have heard it aptly described by a child.

I used Goya’s Giant White Corn posole in this recipe, but there are many other kinds of posole available. When I have used up what I have, I want to try this red posole, and maybe some blue posole.

If you do not eat pork, you can substitute lamb in this recipe and it is utterly delicious.

If you do not eat meat, you can substitute a nice firm mushroom for the meat, or just make a corn and bean stew. In New Mexico, meatless versions of the dish are often used as a side dish for holidays.

You can use whatever chiles you want with the dish; I just happened to have poblanos and ripe serranos. I liked the sweetness the ripe serranos added.

You can add about a teaspoon of honey to bring out the natural sweetness of the pork. Just add it at the same time you add the pork. (You can use sherry or broth instead of the beer for the deglazing operation as well.)

You can add sweet bell peppers to the dish if you like, along with the chiles. I think ripe ones taste better than green ones in this dish, however.

You can leave out the beans, or add different beans if you like. Cannelini beans are very nice, though if you use white corn posole, there is no color variation. Black beans might be fun.

To learn more about pressure cookers, I suggest Lorna’s Sass’ books, Cooking Under Pressure and Great Vegetarian Cooking Under Pressure. While I have never used her recipes as written, I have found that the general information in her books is very good, and the cooking time chart for dried beans in the latter book is the best thing since sliced bread. She is very methodical and her instructions are approachable, and I have used her recipes as a jumping off point for constructing my own pressure cooker specialties for several years.

Food in the News, Again

That may seem like a “well, duh!” sort of declaration, but apparently lots of researchers have been studying the idea that families who dine together produce healthier, happier, more successful children.

This research supports the conclusion that family meals are important to close familal communication and bonding and leads kids to model the behavior (and eating habits) of their parents.

The Columbus Dispatch reports on the recent studies linking family meals with lowered rates of drug use and higher grade point averages; however the story also notes that only 52% of US families eat dinner together regularly, even though three quarters of respondants felt that it was important to have family meals.

The June/July 2005 Eating Well Magazine claims that only one third of American families eat together regularly, however, many benefits await the lucky kids who do eat with their parents seven or more times weekly.

“With pressures on parents to churn out high-achieving kids by loading them up with extracurriculars, says Doherty, opting out of these activities in favor of family dinner “means going against the norm.†In fact, national surveys suggest that only about a third of American families usually eat dinner together.

Ironically, family meals might do more for children’s well-being and achievement than any soccer program or French-immersion class. When Doherty’s colleagues at the university’s Center for Adolescent Health and Development surveyed 4,746 Minneapolis/St. Paul middle school and high school students for Project EAT (Eating Among Teens), they found that the kids who sat down to meals most often with their families—seven or more times weekly—tended to have higher grade-point averages and were more well-adjusted in general than those who ate the fewest family meals (two or fewer per week). They were less likely to feel depressed or suicidal, to smoke cigarettes or use alcohol or marijuana—even when the researchers factored out issues like race, family structure and social class. “Family meals were a potentially protective factor in these kids’ lives almost across the board,†declares epidemiologist and study co-author Diane Neumark-Sztainer.

What’s more, children who eat regular meals with their families also eat more healthfully, according to Project EAT and other studies—in general, taking in more fruits and vegetables and calcium-rich foods, fewer soft drinks and snack foods. They may also have a lower risk of disordered eating: Neumark-Sztainer and her colleagues noted fewer reports of extreme weight-loss diets or binge eating in kids whose families placed a high priority on regular family meals. “The associations were especially strong among girls,†she noted.”

So what is the moral of these two stories?

If you have kids, eat with them. Preferably cook with them. Stop with the bazillions of after-school hyperfocused extracurricular activities, and sit your butts down for at least one meal a day together. Your kids will turn out better for it, and who knows?

Maybe you will turn out better for it, too.

(I am betting that you will.)

The Restaurants of New Orleans

When I was cooking the nam sod on Saturday night, Bry informed me that Cafe du Monde is still standing in New Orleans, which lifted my spirits a bit. I’ve never been there, but I do love their chicory coffee and have made beignet more than once to have with said caffeinated gloriousness; the knowledge that the font of coffee and fried dough goodness was yet standing made my heart soar. Other landmarks of the French Quarter are yet extant, though of course, damaged, probably because the Quarter stands on fairly high ground.

I’ve been waiting to hear news of the other famed restaurants of the city, and picked up a couple of leads here and there. In the past day, however, I have come across news stories specific to the fate of some of the jewels in the crown of a great food city.

At Decanter magazine’s website, I learned that “New Orleans restaurateurs fear for future of culinary ‘Jewel of the South'” With a headline like that, one expects misery and pessimism, but on the whole, the chefs and restaurant owners of New Orleans plan to rebuild. Susan Spicer, of Bayona, probably lost everything in her restaurant including an 8,000 bottle wine collection in the attic. However, she resolved to make certain that the culinary heritage of the region is not lost.

“I have no idea what the future holds for restaurants down there. But I believe that somehow we will band together to keep the food culture alive and well, even if it means feeding emergency, rescue and construction workers on po’ boys and red beans for a year or so.”

You go, woman. That’s a perfect example of the spirit of the South: tenacious and tough, yet gracious and giving, all at the same time.

Decanter also reports that culinary professionals around the US are putting together fundraisers and job information for the displaced restaurant workers of New Orleans.

This morning’s New York Times featured an article entitled, “Crawfish Etouffe Goes into Exile.”

While the expected dire statistics are quoted liberally (nearly 10 percent of the labor force worked in the 3,400 restaurants that once fed the city), the overall tone of the piece is one of hope and optimism.

“We have been instructed by the matriarchs that we will rebuild,” Brad Brennan, of the family that owns the famed Commander’s Palace and eight other restaurants, said from his office at Commander’s Palace Las Vegas. “There was no hesitation.”

The matriarchs are Mr. Brennan’s aunt, Ella Brennan, and his mother, Dottie Brennan, who was evacuated to Houston, where the family also has a restaurant.

Mr. Brennan said it was too soon to know the extent of the damage, but all of the 800 employees of the Brennan restaurants were accounted for.

John T. Edge, southern food historian, author and founder of the Southern Foodways Alliance, has been working hard to compile lists of chefs and other members of the alliance who are accounted for. In addition the alliance has partnered with the James Beard Foundation and Open Table, a restaurant service, to contact restauranteurs around the US in order to create a job bank for those put out of work by Katrina. (A link to the job bank is on the home page of the James Beard Foundation website.)

I know the media has really focused on the worst aspects of Katrina: the death, destruction, lawlessness and looting. The scope of the tragedy is terrible, and words cannot really convey them effectively, so it makes sense that the reporters return to these horrific aspects of the ever-unfolding story of Hurricane Katrina. But, at the same time, it is nice to see not only the worst in humanity being brought out by this tragedy, but also the best wualities of human nature also coming to the fore.

Restaurant people are good folks. When you work together in the close confines of a kitchen nearly every day for over eight hours a day with folks, they become your family. You bond with them in ways that you don’t bond with coworkers in other professions, and so when something happens, bad or good, you all share in that fortune. This naturally extends to other restauranteurs; in a lot of ways, we are seeing proof that the restauranteurs in the US are one huge family, who give aid and support to each other.

That story made my day.

Eating People Made Cows Mad?

Now, you knew I couldn’t do another installment of Food in the News without having something about BSE in here, it being my favorite political hobbyhorse, (hobbycow?) to ride. And really, if it weren’t for the fact that there seems to be a new story about BSE coming out every week or so, I wouldn’t include it here. But there is always new information coming out and who am I to withhold information?

The Washington Post reported last week that there is a new theory of how BSE came into existence back in the 1980’s, and it is a doozy. They picked up the story from the British medical journal, The Lancet, which reported that BSE may have arisen from the practice of feeding British cattle meal ground from bones which had been contaminated by human remains of victims of a human variant of the disease.

Yeah, basically, it may have come about because somebody unknowingly fed some cows Soylent Green and it went all wrong. (Of course, if you take into account the fact that cows don’t naturally munch on bones and that maybe they shouldn’t have been eating any bones, much less human bones in the first place, well, you know what I am going to say. It was all a dumb idea in the first place.)

The gist of it is this: back in the 1960’s and 70’s some brilliant person in the UK decided to give cows feed made partially from bones. But there weren’t enough bones hanging around in the UK to feed all the cows, so they sent to India to get some more. In India, it is customary to dispose of human remains in the sacred Ganges river. It is also customary for members of the lower castes to make money by collecting bones and animal remains from around the banks of said river to sell for use in fertilizer and animal feed production.

In those decades, apparently lots of bones, bone bits and remains were shipped to the UK from India to be used in cattle feed. A couple of British scientists think that it is possible that human remains of victims of the human form of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, may have been mixed in there and thus was eaten by the cows and then led to the rise of BSE, which then was passed on by feeding blood and bone meal from infected cows to other cows.

I am not sure about this theory. It is possible, but CJD is a fairly rare disease; scrappie, the form of the disease that infects sheep is much more common, so I find it more likely that it was diseased sheep remains ground into cattle feed which started the whole Mad Cow ball rolling.

But, it has a kind of science-fiction/horror symmetry that is alluring. Human bodies infected with a human disease are fed to cows who develop a bovine form of the disease, which is then fed to humans who develop a variant on the first disease which started it all.

But whatever started it, I can say this:

If people just recognized that cows are vegetarians and shouldn’t be eating meat or bones, we wouldn’t be in this mess, now would we?

Okay, and just because I find this story to be too weird to ignore:

Willy Wonka’s Nightmare: Nazis Planned to Make Chocolate Bombs

I found this one on slashfood, and it was too freaky to pass up.

ABC News reported yesterday that, newly released files from MI5 reveal that the Nazis had plans to make grenades disguised as chocolate bars. (Talk about a lot of bang for your buck.)

These devices were to be made of steel that was then coated in real chocolate, and would be detonated when an end was broken off.

They also had plans for exploding “Smedley’s English Red Plums in Heavy Syrup.”

No one apparently knows if any of these explosive confections were ever made, however.

Which is just as well, since I am having visions of some Nazi chocolatier cum mad-bomber cooking up insidious delectables a la the film, “Chocolat.”

Only instead of seducing people into throwing off the shackles of conventional behavior and the status quo, these confections would cause widespread death and mayhem.

Like Willy Wonka in jackboots or something.

With Oompa-Loompas doing song and dance numbers a la Mel Brooks’ “Springtime for Hitler” from The Producers.

Okay, I am going to step away from the keyboard for a while and not think of chocolate-making Nazis.

It is hurting my head.

Disaster Relief for New Orleans Hospitality Workers

New Orleans is one of the top restaurant cities of the United States; as such, you know that there are a whole lot of chefs, kitchen workers, prep cooks, line cooks, dishwashers, bartenders, bar backs, servers, hosts and hostesses who are currently out of a job. Some of them evacuated, and some of them stayed behind, but most of them are looking at a situation where they are not likely to be employed in New Orleans for a long time.

In light of that, I am happy to see that not only is there a relief fund being set up specifically for the hospitality workers who put their all into making the Big Easy one of the most gracious foodie paradises our country had to offer.

Go to the Commander’s Palace website and read about the fund, and maybe throw a donation in that direction. (And while you are at it, don’t forget The Red Cross, America’s Second Harvest and Noah’s Wish.)

Once you are there, you will notice that they have also set up a message board for the restaurant workers affected by Katrina, so people can get in touch with each other and pass information back and forth about who is where, what is happening, and how everyone is doing.

Kudos to the good folks at Commander’s Palace for their work on behalf of the entire hospitality community in New Orleans.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.