Some of My Memories of Canning

I was recently invited by Dave Tabler, author of an excellent, interesting blog called Appalachian History: Stories, Quotes and Anecdotes to write a guest post on how the art of canning has changed from when I helped out my Grandma on the farm, and now.

So, if anyone is at all interested in hearing a little bit of reminiscence of my childhood growing up and spending lots of time on the farm, I invite you to hop over to Dave’s place to read Blanching, Boiling, Packing and Processing.

And, while you are there, check out the other great stuff he has on the site–even though it isn’t all about food, it is still interesting from a cultural and historical perspective.

I’d also like to apologize for the lack of any other post today; my Internet was down from early this morning until tonight. So, no post today–if you need your daily fix, dash on over to Dave’s and see what’s cooking there.

Preserving the Beauty of Tomatillos For Winter

Tomatillos are a gorgeous fruit, and they are an integral ingredient to one of my favorite cooking sauces from North America–salsa verde. The fruit, which is encased in a papery husk like a leafy Chinese lantern made of mulberry paper, is often thought of as simply green in color, but the truth is, the hues it comes in are myriad. Subtle shades of kiwi, celedon, celery and leaf green are mixed with butter yellow, cream, and golden mushroom tones. Some fruits are even speckled and streaked with dusky violet which complement the greens and yellows in a way that many painters and interior designers would envy.

There are a couple of farmers who grow tomatillos here in Athens, and they seem to have had a bumper crop this year. Like the tomatoes which have been extremely flavorful (probably because of the very long summer drought we have had), this year’s tomatillos have been fairly bursting with flavor. Not simply tart, but also sweet, with a tangy pineapple fragrance and a rather herbal, woody tang, these tomatillos were perfect for making some salsa verde to can for the winter.

Nearly every ingredient in this salsa is local: I paired the local tomatillos with red or violet sweet bell peppers, and plenty of red onions, garlic and chilies. The hot version had green jalapeno, poblano and Anaheim chilies, while the mild had just poblano chilies.To raise the acidity to safe levels for canning, white vinegar was used, but significant amounts of lime juice were also added, while cilantro, cumin and smoked paprika boosted the flavor. Of course, there is also some salt to round out the flavors and keep the salsa from tasting flat.

I adapted the recipe from The Ball Complete Book of Home Preserving which is edited by Judi Kingry and Lauren Devine. The only things I changed about were the types of chile peppers and the seasonings–it is not a good idea to change the amounts or proportions of acidic to non-acidic ingredients in recipes that are going to be put up in a hot water bath (non-pressure) canner. This is because the acids used in these recipes are part of what helps prevent bacteria from growing in the canned food.

Cooking it is simplicity itself; you just chop the ingredients–I did the tomatillos in medium sized dice, and the peppers and onions in small dice, and minced the garlic and cilantro–and then put everything in a pot, bring it to a boil, turn it down and simmer it for ten minutes. I find that the colors look especially lovely in the uncooked salsa–not only does the red onion boost the sweetness of the salsa and complement the natural sugars in the fruit, but the violet color, even in the finished, canned product, looks lovely flecked through the variegated greens of the salsa.

The recipe I give here fills five pint jars or ten half pints. Whether you pack into the larger or smaller jars, the processing time is the same–you boil them in the covered canner for fifteen minutes. Then, remove from heat and let sit for five minutes before opening the canner and lifting the jars from the water.

So, what do I intend to do with my finished salsas verde?

Make enchiladas verde, of course! Or chile with pork and white beans….mmm.

There are lots of possibilities for soul warming foods to be made with this salsa in the coming winter months.

Tomatillo Salsa For Hot Water Bath Canning

Ingredients:

11 cups husked, cored and chopped tomatillos

2 cups diced red onion

1 cup green Anaheim or New Mexico chiles, diced finely

1/2 cup green jalapeno chiles, diced finely

1/2 cup green poblano chiles, diced finely

8 cloves garlic, minced

1 cup white distilled vinegar

8 tablespoons lime juice

2 teaspoons ground cumin

4 tablespoons finely minced cilantro

1/2 teaspoon smoked paprika

1 teaspoon salt

Method:

Wash five pint or ten half pint jars, their lids and rings thoroughly in hot, soapy water and rinse well.

Fit jars in the rack to a three-quarters full hot water bath canner, lower into the water, and bring to a boil. Lower heat and simmer for ten minutes. (Make sure water comes over the top of the jars and fills them all the way up. Turn off heat and allow jars to sit

Put lids in a saucepan and bring to a simmer–not a boil–and allow to simmer for ten minutes. Turn off heat and keep the lids warm.

Put all the ingredients to the salsa in a clean, heavy bottomed dutch oven or stockpot. Bring to a boil, stirring constantly, then turn heat down and cook at a vigorous simmer for ten minutes, stirring now and again. Turn heat off of salsa.

Following the instructions in my post on pressure canning–fill hot jars with hot salsa, and leave 1/2 inch of headspace at the top. Make sure there are no air bubbles in the jars, and wipe rims of jars, then top with a lid and screw down the ring. Do not tighten ring–just scew it on until it is firm, but not tight.

Put filled jars back into rack in canner, and lower them into the water. Make sure the water covers the jars. Bring to a boil, cover the canner, and process at a full boil for fifteen minutes. Turn off heat and remove canner lid. Let the jars cool for five minutes, then remove from the canner with jar lifter and set on a folded clean towel on your counter away from drafts. (If your kitchen is drafty, or your counter is near an open door or window, cover the jars with another clean towel.

Leave undisturbed for about eighteen hours. Check to make sure the lids have sealed properly–they should be concave and you shouldn’t be able to easily pry the edges up–then tighten the rings on the jars, wipe the jars down and store them in a cool place out of direct light.

Makes ten half pints or five pints of salsa.

A Meditation on Heads-On Shrimp: To Suck, Or Not To Suck?

Aren’t they so pretty? They look like a pile of tiny dragons to me–all fierce with pointy scarlet and pinkcarapaces and claws and long graceful antennae. I can easily imagine them soaring among the roiling clouds of a thunderstorm, tossing balls of shimmering blue lightening back and forth at each other, their tails curling up and around in sinuous swoops and whorls.

Not too many Americans outside of the Gulf region have seen, much less eaten heads-on shrimp. Shrimp fishermen of course have not only seen shrimp with their heads intact, but have probably also eaten a few of them. Regular folks may have eaten some shrimp heads at sushi bars where they are often served deep-fried (apparently, they are shatteringly crunchy and taste like the ultimate shrimp chip–I will have to try one at my nearest opportunity) and Asian-Americans are probably quite familiar with shrimp heads and their fantastic flavor, but for the rest of us–especially those of us who were born and raised in landlocked states–shrimp heads are an unexplored territory consisting of the mysterious and possibly frightening innards of a crustacean.

I know that I had never eaten the head off a shrimp before in my life, but when I bought a pound of live shrimp at the farmers market on Saturday, I didn’t have much of a choice, really. In order for shrimp to be sold live, and thus completely and utterly fresh, they must have their heads attached to the rest of their bodies. It is just the way of things–decapitated shrimp cannot be sold alive.

I bought them, and the faculty member of the Hocking College Fish Management and Aquaculture Program who’d help hatch and tend them, sold them to me handed me a plastic trash bag filled with ice and shrimp. I put them in the trunk of our car and merrily danced off to home where I lovingly placed them in the refrigerator with another heaping pile of ice to put them into a tranquilized state. And then, we went off to do more errands, and I tried to put the thought of the shrimp heads out of my mind. But really, even as we browsed in the bookstore, and even as I showed Kat picture books, and shopped for magazines, in the back of my brain, I was thinking, “I know Zak won’t eat the heads. And no matter how good they are, I cannot possibly eat the heads from a whole pound of shrimp on my own…so what do I do?”

See–the thing is–even though Zak was born in Baltimore and raised in Miami, Florida, his taste for seafood was acquired at a very late age, and blossomed under my influence. That means he spent the first twenty years of his life in two places known for fantastic crustaceans, and he never touched a single one of them. And though he is a serious danger to boiled shrimp now, and I have seen him peel and eat his way through a pound of them all by his skinny lonesome self, those shrimp were sans heads. I was pretty sure that I could never sell him on the idea of twisting off the head of one of the wee beasties, and sucking out the treasures that lay hidden inside, no matter how sweet and intensely flavored they were.

When it was time to cook them, we called our friend Dan, and he came over to help us out with the shrimp eating. He also stayed in the kitchen to watch me clean, cook and partially shell the shrimp, and he helped take some of these photographs you will see here. I didn’t bring up the issue of the heads as I pulled the shrimp out of their bed of ice, and lay them in a colander to give them a good rinse under cold running water. What I did notice, because it was impossible to miss was the fact that several of these beautiful crustaceans were females–it was patently obvious that they were because of the copious amounts of roe–eggs–they were carrying in their back swimming legs.

I felt like a natural history lecturer as I pointed out to Zak, Kat and Dan the female shrimp and their roe (that would be those orange splotches along the tails of some of the shrimp in the photo of them raw in the colander). Now, I have never eaten shrimp roe, but I have eaten caviar, salmon roe, flying fish roe and crab roe, so I knew it would be tasty. I just wasn’t sure how my dining companions would feel about it.

They did crowd around to see the eggs when I pointed them out, and there was commentary about it, but no declarations of desire to eat it were forthcoming.

So, I decided that what I would do was cook the shrimp whole in a boil flavored with beer, lemons, cayenne chiles, whole black peppercorns, garlic wakame seaweed and Chesapeake Bay Seasoning. After they were done (a process which would take bare minutes), I would fish them out of the boiling liquid, and dismember them, cutting off their heads, which would be tossed back in the pot, and scraping off the roe, which would also return to the simmering liquid.

When the shrimp were shelled, I’d add the shells, too, and let this mixture simmer for about an hour, until an intensely flavored shrimp stock was produced. This, I figured, I would use to make shrimp etouffee next week if the shrimp folks were back and selling their delightful little dragons again. (And, if they aren’t, I will order some really good Gulf shrimp from an online purveyor, because I am not wasting that stock on some pallid frozen nasty things from the supermarket.)

So, that is what I did. I made the boil up–two bottles of Sam Adams beer that the in-laws bought when they were here last, three lemons, juiced, and then cut into quarters and tossed in with the beer, four fresh cayennes, cut into chunks, six cloves of garlic peeled and crushed, a teaspoon of black peppercorns, two tablespoons of dried wakame seaweed, about three tablespoons of Chesapeake Bay Seasoning and about a cup or so of water. (I could have used Cajun-Creole seafood seasoning, but as both Zak and Dan were born in Baltimore, Maryland, I think that there may have been a mutiny on my hands if I had suggested such a thing. As it was, Dan had to run down the hill to his house to fetch his jar of Chesapeake Bay seasoning because mine was hiding,) This mixture was brought to a boil in a medium sized pot over high heat.

Then I put the shrimp into the boiling liquid a few at a time. The cold from the ice had sedated them to the point that I believe that while they were alive, they were in torpor–probably unable to feel a thing. I put them in a few a time because they were not of similar size–they were not sold graded by size at all, so I only cooked a few at a time so I could pull them out when they were just done. I don’t like overcooked shrimp, so I stood over the pot, vigilant for the brightening of the shells as they went from grey-blue to pink and red.

After they were all cooked, I turned the heat down to low so that the pot barely simmered.

This took about two minutes, and after each shrimp was done, I would scoop them out with my wire skimmer and pop them on top of a mountain of ice I had waiting in a serving bowl. There they waited until all of their brethren were cooked, and I could finally pop the question to Dan and Zak: “So, are we going to suck the heads out of these seabugs or not?”

The answer was, quite simply, “Not.” Just as I figured.

No matter–I began the beheading process. Considering that the shrimp had already given their lives to the boiling pot, I wasn’t too worried. All I had to do was put my knife at the back of their heads, where the head meets the tail, and cut between the plates of chitin. After that, I tossed the head back into the pot, and then start clipping through the shell that curved over the back of the shrimp so I could devein them. But low and behold, after I clipped a few shrimp, I realized that the aquaculture students had purged the shrimp before selling them. This means that they withheld feed for a short time before bringing them to market so there would be nothing in their digestive system to clean out. Amazing!

Some viscous yellow fluid seeped from some of the shrimp heads–I figured it was the brain or some organ or another–I couldn’t remember my crustacean anatomy very well from high school. It looked exactly like egg yolk and had a similar rich, unctuous flavor. I felt that I had scored a major victory when I got Dan to taste it. I scraped what was left on the cutting board into the pot, unwilling to lose a single drop of richness and flavor.

I did squeeze the head of one of the smallest shrimp into my mouth. I have to admit to liking it just as well as the crawdad heads I had sucked gleefully from their shells in the past, though the shrimp isn’t as rich and fatty. But the head has the sweetest, most complex flavors–which meant that the stock was going to be fantastic when it was done.

So, I just kept beheading shrimp. I began to feel rather like Robespierre, sending these poor innocent shrimp to the guillotine, -after- boiling them to death. No matter, I kept to my work, though in my head I would name each shrimp with the name of a French aristocrat who died during the Revolution. As I scraped the roe into the simmering stock, I began wondering of a giant, foppish masked shrimp named The Scarlet Pimpernel would come to try and save these defenseless crustaceans from my wicked clutches, but no–they were left to my tender mercies until they were all headless, cleaned and enthroned on a mountain of ice to chill.

So, while the shrimp stock simmered, I put together a simple cocktail sauce–some ketchup, some grated horseradish, some lemon juice, Chesapeake Bay Seasoning and a generous squirt of Rooster Sauce–aka–Sriracha Hot Sauce blended into a crimson incendiary condiment.

How were they?

Amazingly sweet. Dan, Zak and I made terrific messes of ourselves peeling and gobbling down those little headless aristocratic water dragons. The sauce was a spicy foil for the sweet, tender meat, and it was a great appetizer. The shells went back into the quietly simmering stock.

The largest regret I had was that we couldn’t let Kat have any for fear that she may be allergic to shrimp, though neither Zak nor I, nor anyone in our families, is allergic to them–it is best to be cautious with such a potentially lethal allergen She watched us with great big, pleading eyes, but had to content herself with the bread I had torn apart for her to eat. I felt bad because we generally share most foods with her, and she didn’t understand.

Someday, we told her, you, too, can engage in crustacean killing.

How did the stock turn out?

Well, after an hour, I strained it by pouring it through a very fine sieve, pressing down hard on the heads, shells, and other solids to extract every droplet of liquid loveliness I could possibly manage. The rich brown fluid was amazingly complex–flavored with the essence of shrimp along with sparkles of cayenne and lemon, with hops and barley notes warming it from below, and a distinct richness from the roe. The spices danced around the edges, teasing the palate. It will make an great pot of etouffee.

(And I will have to buy extra shrimp so I can also make Thai Chili Basil Shrimp–a dish which is only eclipsed by Chili Basil Squid–but we are fresh out of squid around here.)

When I gave a tiny sip of it to Dan, his eyes rolled back in his head and he tapped a happy rhythm with his hands–which is a supreme expression of gustatory joy for him.

So, the stock is in the freezer, waiting to see if we can pick up a few more pounds of shrimp this coming Saturday for another feast of Ohio aquaculture seafood.

Images And Impressions From Athen’s Farmers Market

Saturday’s farmers market here in Athens was a nearly perfect experience of the diversity that is possible in local agriculture and food producers.

The weather, which was a cool seventy-six degrees F. and sunny, the harvest, which was at its peak for early autumn, showing the best of both summer and fall produce, and the people, who came in droves, both to sell and buy, combined to create a scene which is quintessential Athens. Farmers chatted with customers, friends gathered in small clumps to catch up on gossip, musicians gifted the community with their tunes, and kids dodged and played among the crowd.

Diversity came not only in amount and types of foods available, but was also apparent in the faces of the people throughout the market. An older Mennonite woman sold her amazing yeast donuts fried in lard and glazed with honey and sugar, while down the row, a conservative Islamic man from Pakistan and his American-born wife sold potato and pea samosas, baklava and other treats from India and the Middle East. An international award-winning local pizza place sold European hearth breads baked to a chewy crusty finish in a variety of flavors and shapes, while a native Appalachian farmer sold bitter melon gourds he had grown to a variety of students and faculty from China, India and Thailand. I heard at least three different languages besides English being spoken, and saw foodstuffs which had their origins on at least five continents represented among the offerings.

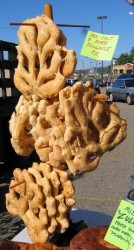

Our Appalachian heritage was well represented by the offerings of Integration Acres, which includes black walnuts and a variety of products made from pawpaws–a native fruit that tastes like a combination of banana, mango and papaya. Chris, the owner of Integration Acres, also sells other products native to the forested hills of Appalachia, such as spicebush berries (I like to think of it as native allspice–that is what the dried, round berries taste like, and it was used to substitute for the expensive spice by settlers in the 18th and 19th centuries), and hen of the woods–a meaty, delicious mushroom which grows on dead or dying oak trees, though it can also be found around maples. Here in Athens County, they can be deep orange in color with a white interior, but I have seen photographs of them ranging in color from cream to deep, chocolate brown.

Chris also produces the first commercially available local cheese in Athens County–he has goats on his farm to help manage undergrowth in this woods. Goats are browsers and help keep his stands of pawpaws from having a lot of competition for water from underbrush. Now he uses their milk to make the most delicious chevre you can imagine–creamy, tangy and tart with a smooth, nutty finish. It was amazingly wonderful–so wonderful that Casa Nueva, our local worker-owned local foods restaurant, has decided to feature a salad made from Chris’s chevre and walnuts scattered over a bed of greens and radish sprouts from Green Edge Gardens on their seasonal autumn menu. Locally grown apples add tart sweetness, and the whole dish is tied together with a dressing that features pawpaw puree. It is amazingly good–so good that I wish all of my readers could come to Athens just to taste it.

The types and amount of food available in Athens is actually quite amazing, and is in fact, getting better all the time. I know that I talk a lot about the bounty of our local food economy here in Athens and the surrounding counties, but in late September, when everywhere you look you see box after box of tomatoes, zucchini, onions, garlic, green beans, apples, pears, grapes, plums, peaches, sweet and hot peppers in a rainbow of colors, winter squashes, carrots, beets, turnips, greens of every type and description, potatoes, sweet potatoes, cucumbers and herbs, it is just hard to fathom how lucky we are here. Once your eyes have taken in the usual vegetables one expects to find in any American farmers market, you begin to notice the more extraordinary offerings. Fenugreek greens in bundles as big as a wedding bouquet. The afformentioned bitter melon. Tomatillos. Chinese long beans. Shiitake, chantarelle and lion’s mane mushrooms. Tatsoi. Bok Choi. Daikon radish. Horticultural beans. Christmas limas. Chestnuts. Hazelnuts. The list goes on and on–if you can grow it in the rich mountain soil of Athens, and if the farmer can get the seeds, someone will grow it.

I haven’t even really expressed the diversity of meat, eggs and processed foods available here.

First of all, about five or six different folks make salsa around here, can it and sell it at the farmers market. You can also find applesauce, apple butter, cider and jams, jellies and preserves to suit any taste. There is local wildflower honey which not only tastes good, but can help you survive local pollen allergies with a less runny nose. There are sauce makers, and juice pressers, bakers, and noodle makers here. Heck, we even have a local winery which makes an elderberry wine to die for–talk about an Appalachian tradition.

And our meat farmers are fantastic. Most of them feed their animals on grass and locally produced hay–all of them pasture their animals and their meat shows the difference such care makes for animals. Not only are the animals healthier and happier in their lives–their flesh is not only tastier but healthier for humans to eat. We have several beef producers, folks who raise heirloom breeds of chicken which give firm, flavorful meat, a hog producer whose pork tastes like the nuts the pigs dig up from the forest floor, a rabbitry and several folks selling lamb and goat meat. Eggs here have rich nearly orange colored yolks from the chickens being raised on grass and a diet of bugs in addition to grain–many farmers here use their chickens for natural pest control and for fertilizing their fields. The eggs are the best you will ever eat–always fresh and always full of omega 3 fatty acids.

Oh, and did I mention that in the fall, you can get live shrimp here? Fresh, live shrimp. Yes, your eyes do not deceive you–those are live shrimp, harvested from the aquaculture program at a local college. More about the shrimp later- let me just say right now that not only were they live, and thus fresh–they were excellent! (I sure hope these folks come back to the market next week, because if they do–I am buying several pounds of the shrimp and making etouffee and Thai chili basil shrimp. Because, dammit–they are just that good. And if these folks don’t come back–I am going to hunt them down at their college and refuse to leave until they sell me some shrimp.)

I am sad to say I didn’t see many folks buying much of the shrimp–but well, I guess that just leaves more to myself, Zak and Dan to eat.

This is what it is like to live in Athens–there is always a food adventure around the corner. Yes, it is a small town, and as such, there are not a lot of places to eat out–not like New York or San Francisco.

But, really, what we lack in opportunities to eat out, is made up for with the raw materials we have to work with, and the lower cost of living.

It is really, truly a beautiful place to live, especially on sunny Saturday mornings in September, when the market is rocking, and the world is alive with laughter, music and fresh food.

Yet Another Reason Why I Support Organic Agriculture: Malformed Frogs

I remember hearing on the news in 1995 that schoolchildren in Minnesota had found a great deal of seemingly mutated frogs whose hind legs were either completely missing, missing extremities, split or who had up to five back legs. I remember listening to the report, looking at the videos of the captured leopard frogs and saying to Zak, “I bet it is heavy metal poisoning or pesticide exposure causing those mutations.”

It was not an unreasonable assumption. Both methyl mercury poisoning and pesticide exposure had been implicated in birth defects in human infants; it is not too far of a stretch of the intellect to assume that groundwater contaminated with these substances could easily penetrate the very permeable skin of amphibians such as frogs and cause similar mutations and birth defects.

I found this discovery of mutated frogs, in conjunction with the news that frog populations are declining worldwide disturbing, not only because it points to a loss of species diversity, but also because frogs are considered “indicator species,” by environmental biologists. Because of their permeable skin through which gases and liquids easily pass, any change in these animals morphology or population is an early indicator that something has changed in the environment. What I assumed that these mutated and disappearing frogs were telling us was that on a wide scale, our groundwater was contaminated with industrial and agricultural chemicals which are affecting these animals. And of course, while it may only affect frogs presently, toxic groundwater is eventually a great threat as the toxins gradually build up, climbing the food chain–the food chain which eventually ends not just with humans, but with our breast-fed infants. (Any and all environmental toxins present in the mother’s body are passed on to her child via her milk. For an in-depth look at this issue, read Having Faith by environmental scientist Sandra Steingraber. She frames her investigation into the human consequences of environmental industrial and agricultural toxins with the story of her own pregnancy and her experiences raising her daughter, Faith. I cannot recommend this book enough–not only is it educationally valuable, it is a very personal look at a global problem–in other words, instead of inundating the reader with statistics and figures–she shows us the human face of our collective disregard for the environment.)

Since the schoolchildrens’ discovery twelve years ago, malformed frogs have been reported in forty-four states; the problem is obviously more widespread than was first thought.

Environmental scientists started studying the problem, and at first, the most popular hypothesis was that it was exposure to ultraviolet radiation (caused by the thinning protective ozone layer) causing the malformed, missing and extra limbs, with agricultural or industrial chemical poisoning coming in as a close second favorite explanation.

One of the first possible culprits studied was UV radiation; it was shown that exposure to UV caused similar limb deformities in both salamanders and frogs, as well as causing eye damage in adult frogs and killing amphibian embryos and larvae. EPA scientists were quick to point out that while UV radiation could be part of the problem, in no experiments had it managed to cause a frog to grow extra limbs such as the ones in the frogs found in Minnesota, and now, all over the country.

Research into pesticide and herbicide contamination at first seemed promising, but later research found that most of these chemicals broke down quickly in the environment and were not likely to have directly caused the malformations. (Herbicides such as Atrazine were found to interfere with sexual development of frogs, by mimicking sex hormones–which is problematic and may be involved in a decline of reproductive capabilities, but they seemed to have no effect in limb development. Mind you–at much higher doses, this environmental pollutant can have similar effects in humans, but let us not worry about that now–the EPA says that there isn’t enough of it in the environment to be causing the documented decline in fertility among human beings that has been going on for the past few decades.)

As the years went on, the most likely candidate to pin the blame for the frog problem became parasitic infection. When I first heard that scientists had found that trematodes, a flatworm or fluke, were the likely cause of the deformities, I was fascinated. These tiny parasites are carried by snails, who are a host species, and then are transferred to frog embryos, where they attach themselves and form cysts, near the posterior end of the body. Studies using tiny glass beads to act as artificial trematode cysts have shown the same hind limb malformations, showing that the parasites are the most likely widespread cause. Analysis of areas where frog malformations were high showed high populations of trematodes in the environment.

Coincidentally, these areas also tended to be areas where agricultural runoff was also high.

For some people, the trematode is the end of the story, taking agricultural chemicals off the hook.

However, some scientists theorized that the reason why instances of parasitic malformation was high in wetland areas where agricultural runoff was prevalent may have to do with pesticides’ probable link between trematode infestation of frog embryos–scientists theorized that pesticides lowered the frogs’ immune systems and cause them to become more susceptible to infestation. This promising lead also ended up being at least partially discredited; while it was found that frog embryos exposed to various pesticides and herbicides had lower white blood cell counts and thus compromised immune systems, scientists failed to study the effects of these chemicals on the hosts of the trematodes–snails–and the trematodes themselves.

Finally, this week, it seems that a direct link has been established between trematode infestation in snails and frogs and agricultural chemical contamination through runoff: it appears to be the use of high levels of chemical fertilizers, carried from fields and deposited in wetlands by rainwater, which is the root of the problem.

How can this be?

Well, when large amounts of pure nitrogen and phosphorus are washed into ponds and other wild waterways, this extra fertilizer causes a very fast growth of algae, called “bloom.” This attracts many snails to eat the algae, and the higher population of snails gives trematodes a larger pool of possible hosts, which then causes a population boom in the parasites, which leads to more frogs being affected. (It is still also possible that runoff of pesticides and herbicides is also affecting the situation by lowering the frog’s resistance to parasitic infestation.)

The reason I found this issue imperative to write about today is because I realized that years ago, my knee-jerk reaction to blame agricultural chemical pollutants was only partially correct. My assumption that there was a direct link between the mutations and the chemicals was false, although my belief that there was a causal link between the two was true.

The lesson of the malformed frogs is this: when humans introduce powerful chemicals into complex ecological systems, it is very nearly impossible to predict all of the consequences. Every action humans take upon an environment causes a ripple effect that changes things far beyond the factors which humans wanted to control in the first place, and these changes may not become apparent until far into the future.

This is part of why I support the use of organic agricultural methods which have smaller, more predictable effects on the environment at large. For example, using organic matter as fertilizer, which must be broken down by the bacteria present in the soil, releases nutrients slowly into the soil, without causing overloads of fertilizer runoff in the waterways. (Algae bloom also causes large fish die-offs in streams, rivers, lakes and ponds by deoxygenating the water and suffocating the fish.) It also helps build healthy soil, which is not just rock dust, but which is in itself a complex ecosystem consisting of organic matter, insects, minerals, bacteria and other microorganisms, worms, nematodes and burrowing mammals. Healthy living topsoil is something that is so complex that many environmental and agricultural scientists say it would take generations of study just to come close to understand it.

These malformed frogs are telling us something–they are telling us to slow down and think before we act. They are telling us to stop doing uncontrolled and uncontrollable experiments on our land, our water, our air, our bodies, and on the whole of the earth, by dumping chemicals hither and yon, because we simply don’t know all of the implications of what we are doing.

I hope we listen, because if we don’t–what happens to the frogs may eventually happen to us.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.