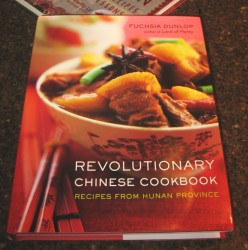

Book Review: Revolutionary Chinese Cookbook

Fuchsia Dunlop opens her second Chinese cookbook with words of wisdom from Chairman Mao: “You can’t be a revolutionary if you don’t eat chilies.” Perhaps the most famous son of Hunan province, Mao Zedong, provides one of the hooks that draws the reader and cook into Revolutionary Chinese Cookbook; the other is provided by the clear evocative words and photographs of the province, her people, and most importantly, her food.

One of the more popular cuisines of China here in the West, Hunan cookery is known for the liberal use of chile peppers as well as for the clear simplicity of its flavors. However, for all of its popularity, the subject of Hunan cuisine has been relatively ignored when it comes to cookbooks, with only a handful of them written in English, and then only one or two being worth the trouble of reading and cooking from. Just as she did for Sichuan cuisine in her first, award-winning cookbook, Land of Plenty, Dunlop immerses her readers into the culture and cuisine of Hunan, demystifying the ingredients, techniques and dishes of the kitchens of peasant and professional chef alike.

The book begins with an concise but clear exposition of pantry items, cooking equipment and techniques for the neophyte. She does not go into as much detail with this section as she did in her first book, and in fact, refers readers to her it for longer explanations of cutting and cookery. However, I don’t hold this as a strike against Dunlop; it does not make sense to repeat material she has already written once. Dunlop explains specialized Hunanese cooking techniques, and ingredients, and enough about general Chinese cooking to explicate the directions in the recipes well enough that a novice can follow them without confusion or questions.

And what about the recipes, then?

First of all, each of them comes with a story; at least two paragraphs of relevant cultural material, personal experience, folklore or history are given with each recipe, and sometimes quite a bit more. The strange and convoluted tale of General Tso’s Chicken, arguably the most famous Hunanese recipe in the world (except Hunan province, where it has only recently become popular) merits more than two pages of background information, because Dunlop set out to get to the bottom of where the recipe originated. I am not going to tell the story here–she is the one who did the research after all, so it is hers to tell–but suffice to say that she tracked down the chef who first cooked the dish. It turns out that he is Hunanese, but he was cooking in Taiwan and the USA, and the dish named for the famous general was his own invention based on Hunanese ingredients and techniques that were cooked to primarily American tastes. (And I swear, I must be the only American who finds that dish to be icky–too sweet and not nearly hot or sour enough.)

Secondly, of the four I have cooked so far, three of them are going to become standards in my home; as in Land of Plenty, the recipes are authentic in ingredients, technique and presentation, though Dunlop suggests substitutions where appropriate. I have found as I have been cooking along that the flavors of Hunanese food are much more clear and pure than those of Sichuan, as the ingredient list tends to be shorter and the techniques simpler. The main flavorings I have used so far have been chiles both fresh and dried, Shao Hsing wine, fermented black beans (which are used with a much heavier hand than they are in Cantonese cuisine–much to my joy as I adore their intense flavor) soy sauce and the intense smokiness of bacon and smoked tofu. It is going to take me some time to finish going through all of the recipes I have marked to try out, but rest assured, I have not come across any which are out and out awful yet, nor have I found any with inaccurate measurements.

Just as she did in Land of Plenty, Dunlop compiled a list of recipes which show the breadth and depth of the cuisine she is examining. There are dishes, such as Peng’s Home-Style Bean Curd, and Chairman Mao’s Red-Braised Pork, which represent the best of the countryside cookery of the peasant class. These dishes are all simply prepared, filling, and bursting with robust flavors which strongly season the staple food of plain steamed rice. At the other extreme are fussy recipes such as Yolkless Eggs with Shiitake Mushrooms, which involves blowing eggs out of eggshells, separating the white from the yolk, then cooking the whites into a sort of custard filled with mushrooms as the “yolks” inside the hollow eggshells. These recipes represent the heyday of Hunan restaurants, back in the 1930’s when chefs strove to outdo each other in the presentation of ever more extravagant and dainty banquet dishes.

In between these two extremes, Dunlop strives to fairly and accurately represent the sorts of foods eaten by both the ordinary people and the elite of Hunan, as well as the foods of minority populations whose culinary traditions differ in significant ways from the majority.

The book is an embarrassment of culinary riches, one which will keep any curious culinary adventurer busy in her kitchen for weeks.

In short, Dunlop has done it again.

She has traveled to China, rolled up her sleeves and cooked her way from one end of Hunan province to the other, gathering recipes, legends, history and food lore as she goes, distilling it all down into a remarkable work that is as much a document of a land and its people as it is a cookbook.

I cannot recommend this book highly enough.

(Tomorrow, I will start presenting recipes I have tried from the book for your enjoyment.)

A Curry of One’s Own: Murgh Padmavati

Sometimes, one has a flavor or a color or a texture in mind, and one wants to create a dish to showcase it. Sometimes, one has all three of these culinary qualities jostling about in one’s thoughts, all clamoring for expression, leading the cook to dream during slumber and waking, of a dish that will satisfy her creative urges, until a vision erupts before her mind’s eye and explodes into her taste memory with the force of urgency and one must dash for the kitchen or risk madness from frustrated culinary longings.

I have been wanting a chicken curry for a long time. Several weeks, in fact. However, I had been stymied by a lack of chicken in my freezer and a sudden dearth of locally produced good quality chicken in the markets. However, by luck, I found a wayward package of chicken breasts from a local farm which had escaped my freezer inventory sheet, and discovered that a local health food emporium stocked free-range organic Ohio Amish raised birds, so I picked up a couple more breasts and set out for the kitchen.

I didn’t want just any sort of chicken curry. Nor did I want one from a cookbook, for lo, the curry I hungered for already existed in my mind, and was fit for a royal table.

It would feature a pale, coconut milk based sauce, with onions cooked only to a golden brown, and pureed into a cream-colored paste. (It is said that the Mogul Emperor Shah Jahan liked banquet dishes that were pale in color, like alabaster, so there is precedent.) It would be redolent of garlic and fragrant with ginger, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, coriander and just a whisper of black pepper. A touch of fire from a green chile and a kiss of sour from tamarind would round out the curry sauce in which the chicken pieces would be braised slowly. At the end of cooking, chunks of fresh mango would be added to give another layer of tartness along with a hint of velvety sweetness.

After the mango had cooked for a bare few minutes in the simmering, now thick sauce, a verdant paste made of cilantro leaves and stems, mint leaves, green chiles and a touch of raw onion, would be stirred into the curry, staining the sauce a fresh, cooling green, while bringing a further layer of flavor to the dish. Salt and a bit of tamarind concentrate would be added to taste, and a sprinkling of garnet-like pomegranate seeds would dot the dish just before serving, giving a contrast in color, flavor and texture.

The colors of the still unnamed curry that had been haunting my thoughts for weeks reminded me of the vibrant tones of sari silks or the polychromatic depictions of Hindu deities popularly hung in temple rooms by the devout all over India and the world. They also called to mind a myriad of gemstones in a young princess’s jewelry box: topaz, emerald, jade, garnet, ruby and ivory.

It was that image that gave me the inspiration for the name of my dream curry, Murgh Padmavati. Padmavati, which means “like a lotus,” or “abundant lotus,” is the name of a Sri Lankan princess/heroine from the epic Bengali poem of the same name by the poet Alaol. In reflecting on the meaning of the name, I realized that the sauce was as green as lotus leaves, with the cream colored chicken, yellow mango and deep carmine pomegranate seeds reflecting the intense colors of lotus blossoms.

At any rate, here is how I finally brought my dream curry to life; I hope that everyone enjoys it as much as I did.

Ingredients:

1 cup thinly sliced onion (reserve 2 slices for later)

1 19 ounce can coconut milk (I used Mae Ploy brand)

water as needed

6 large cloves garlic, sliced

1 1/2″ cube fresh ginger, sliced

1 fresh green chile (I used a green cayenne), sliced

10 green cardamom pods

1 tablespoon coriander seeds

1/2″ piece cinnamon stick

1/4 teaspoon black peppercorns (you can add more–I only used this many because of my allergy to them)

5 whole cloves

pinch ground nutmeg

1/8 teaspoon fennel seeds

1 pound boneless skinless chicken breasts, trimmed and cut into bite sized pieces

1″ cube fresh ginger, cut into thin julienne slivers

2 tablespoons tamarind concentrate

1 ripe mango, peeled and cut into small cubes

1 cup cilantro leaves and stems, washed and picked over

1/4 cup fresh mint leaves, washed and stemmed

1/4 cup dessicated unsweetened flaked coconut

2 fresh green chiles–stemmed and cut up–again, I used cayenne

2 reserved slices of raw onion

salt and tamarind concentrate to taste

pomegranate seeds and cilantro leaves for garnish

Method:

Using a heavy bottomed skillet or dutch oven, melt about two tablespoons of coconut cream from the top of the coconut milk can until it is liquid and bubbly. Add onions (except for two slices) to the coconut cream, and cook, stirring over medium heat. Brown the onions gently to a golden brown color, but no darker! (This is one of the few times you will hear me admonish a cook to not brown onions well for an Indian style dish, but the reason for this is because I do not want the browned color or flavor in the curry. This curry is lightly flavored, pale and aromatic. If it were dark, the addition of the green herb paste at the end would result in a very ugly looking curry, and the flavor would be completely different.)

As the onions cook, lightly browned bits of onion juice and coconut cream will adhere to the pan. When this happens, in order to add this flavoring agent back into the curry, add a tiny amount of water to the pan–about two to three tablespoons at a time, and use this to deglaze the bits from the pan by pushing the onions and water around the pan surface. The onions will take up the colored bits and will go on cooking. Do this as needed until the onions are golden as pictured above.

Take pan off the heat and grind up the onions into a creamy colored and textured paste. Set aside.

Grind the ingredients listed from the garlic to the fennel seeds into a stiff paste.

Add the rest of the coconut cream to the pan, and put it back on medium heat. Add the spice paste and cook, stirring for about two minutes–until it is very fragrant. Add the chicken and cook, stirring, until the outside is lightly colored brown and ivory, with very little pink still showing on the outside. Add the slivers of ginger, and keep stirring. Add the onion paste, and the tamarind concentrate, and cook for another minute. Add the coconut milk, all at once, and if anything has stuck to the bottom of the pan, scrape it up, as you did before with the water. Cover loosely, put heat down to low and braise chicken pieces until cooked through and tender. Remove lid, and if necessary, allow sauce to simmer further to reduce until it will coat the back of a spoon. Add the mango cubes at this time.

Meanwhile, as the chicken cooks, grind the herbs, coconut flakes, green chiles and reserved raw onion slices into a thick, very green paste.

When the curry sauce is at the desired thickness, swirl in at least 1/2 of the green herb paste, stirring until it is well combined. Serve the rest of the paste in a small bowl on the side so diners can add more heat and herbal flavor as they like to their servings of curry.

Taste and add salt and tamarind concentrate as needed to balance flavors. The curry is light and refreshing in flavor with a hint of tang from the tamarind, a bit of heat from the chiles, a sweetness from the spices and garlic, and the fresh fragrance of herbs and fruits.

Sprinkle each serving with pomegranate seeds and cilantro leaves.

Note:

I am pleased to say that this dish was the one I used to break in my new pretty–my Generic Winter Holiday gift from La Belle-Mere Tessa–a glorious Le Creuset braising pan. (There it is, looking really pretty in the photo above.) Not only did it cook the curry beautifully on very low heat, it kept it warm all through serving, and, I have to admit to the fact that its gorgeous green color was what put the idea of finishing a pale curry with a green herb paste in my mind. It is what started me thinking and dreaming of Murgh Padmavati, so, let’s all give thanks to Tessa, for she is the bringer of culinary inspiration!

It’s HERE!

Pardon me while I jump up and down (virtually) for a while and do the happy Barbara dance, because a long-awaited cookbook is not only finally out, but it is out a full month earlier than I expected!

Yes, folks, Fuchsia Dunlop, the author of the definitive Sichuan cookbook in English, Land of Plenty, has taken herself to Hunan province in order to bring us an equally beautiful and well-researched volume on the cuisine of that region.

There is really a dearth of good cookbooks in English on Hunan food; the best is Henry Chung’s book, Henry Chung’s Hunan-Style Chinese Cookbook. (And, it is, alas, out of print.) After reading and cooking through Dunlop’s first book, I have been on pins and needles waiting for the publication of this second book.

Needless to say, look for a review of the book soon, along with a presentation of several recipes from it in the next week or so. Zak looked at the pictures and recipes and said, “So, uh, we are having Hunan for dinner right?”

(The answer was no, because I had a new chicken curry planned, and he suffered through it, though he kept glancing longingly at the cookbook as he dished up a second helping of rice for himself.)

Keeping and Breaking With Tradition: Pork Vindaloo with Coconut and Mango

Vindaloo, which is well-known as the “hottest” of curries available in most American and British Indian restaurants, is not just about tongue-searing heat. The name, which cames from the Portuguese “Vinha d’Alho”, which translates to “with wine and garlic,” does not have anything to do with potatoes (though they are a common ingredient in most US and UK curry establishments, nor chiles.

It is a dish that dates back to the colonial period, which Portuguese spice merchants took over the ports of Goa, and established a tradition of Christianity and pork eating, a rarity in the predominately Hindu and Muslim Indian subcontinent. The pork of vindaloo was originally cooked with plenty of garlic and wine or wine vinegar; however, in the hands of Indian cooks, it was improved greatly with the addition of mustard seeds, ginger, and the newly arrived and enthusiastically adopted New World chiles. It is a fiery dish; mustard, garlic, ginger, chile and onions all contain differing levels of heat and pungency, but I think that the idea of eating it hotter and hotter rather misses the point of the glorious tapestry of flavors that a well-made vindaloo will send dancing across a diner’s tongue.

I have eaten vindaloo in many restaurants, though never the traditional pork version. I guess it is because I first learned my Indian cooking and palate from a Muslim family, but I always thought that pork curry sounded somewhat odd and wrong. So, I always ate lamb or chicken versions, both of which are quite flavorful indeed.

I started cooking my own chicken version of it years ago, patterning it after the way they made it at Akbar Restaurant in Columbia, Maryland, which is one of the two best Indian restaurants I have had the pleasure of eating in here in the states. The addition of mango at the end of the cooking process was my own innovation; I have never seen any other recipes using the lush fruit in vindaloo. I think that is a shame, because the sweet, cooling fruit is the perfect counterpoint to the mustard and chile-rich curry sauce with its browned onions and slivers of ginger.

The other night, when I was thwarted in my attempt to buy fresh local chicken, but I had found mangoes on sale, I decided to use the locally produced pork I had on hand to make my own mark on the original dish. Not wanting to cook it exactly the same way I cook the chicken dish, I decided to play with the masala mixture, and instead of using vinegar in the marinade, I opted for the more subtle, fruity souring agent of tamarind, in the form of tamarind concentrate. (There are a few recipes, most notably those by Julie Sahni, which specify the use of tamarind rather than the more traditional vinegar.)

Finally, I remembered reading one recipe out of all of my Indian cookbooks (I have over thirty-five of them at last count) which specified the optional use of coconut milk in the cooking of pork vindaloo. This would be the recipe in Madhur Jaffrey’s book, Quick and Easy Indian Cooking, which is my bible when it comes to using a pressure cooker to make curries that taste like they have simmered all day, even if I don’t have hours to hang out in the kitchen. I don’t really think that the use of coconut milk is traditional in the making of this Goanese dish; none of the other cookbooks in my collection specify its use. However, when I tried it out with the pork, the modified masala and mangoes, it really made a spectacular curry that had all of the spice and aroma of vindaloo along with the sweet richness of coconut milk and the zing of mango.

It was, in a word, delicious.

Now, I have to work on a lamb version of this dish for when my Muslim friends come to visit.

Pork Vindaloo with Coconut and Mango

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons mustard seeds

1 tablespoon cumin seeds

1 black cardamom pod

1 teaspoon coriander seeds

1 teaspoon fenugreek seeds

1/2 teaspoon black peppercorns

3/4″ piece cinnamon stick

2 teaspoons ground turmeric

1 teaspoon ground cayenne pepper (optional)

2 teaspoon ground sweet paprika

2 cloves garlic, sliced

1/2″ cube ginger, sliced

3 tablespoons tamarind concentrate

1 1/2 pounds lean pork loin, cut into 1″ cubes

3 tablespoons canola, peanut or mustard oil

1 large onion, cut into paper-thin slices

2″ cube ginger, cut into thin jullienne strips

2- 5 fresh cayenne or Pakistani chiles, cut into thin slices on the diagonal (adjust heat level to your preference)

5 cloves garlic, cut into thin slices

1 cup canned coconut milk

1/2 cup water

tamarind concentrate to taste (I used about two more tablespoons)

salt to taste

1 cup roughly chopped cilantro

2 fresh ripe mangoes, peeled and diced

pomegranate seeds for garnish (optional)

Method:

Put first eleven ingredients into a food grinder like the Sumeet (or, use a coffee grinder for the dry spices and then put them into a blender with the wet ingredients) and process into a thick paste. Toss the cubes of pork with this paste and cover and marinate in the refrigerator for at least two hours, up to overnight.

When you are ready to cook the curry, heat the oil in the bottom of a pressure cooker or a large, heavy bottomed dutch oven. Add the onion and cook, stirring constantly, until it turns a medium golden brown. Add ginger and fresh chile slices and continue stirring until the onion is dark reddish brown and very fragrant. Add garlic and marinated pork and cook, stirring, until the meat is browned on all sides. Add coconut milk and water, and scrape up any browned bits that adhere to the bottom of the pot.

If using a pressure cooker, bring liquid to a boil, lock down lid and set at high pressure. Cook at high pressure for twenty minutes, then remove from heat and allow the cooker to reduce pressure to normal naturally as it cools–a process which will take about fifteen minutes. (If you are not using a pressure cooker, add more water and simmer, covered until pork is tender–about two hours–adding water as needed to keep curry from drying out and sticking on the bottom.)

When pressure is normal, open pressure cooker and bring vindaloo to a boil again. Cook, stirring, until the sauce reduces and thickens somewhat–when it coats the back of a spoon, it is ready.

Add tamarind concentrate and salt to taste, and stir in cilantro and ripe mangoes. Serve with steamed basmati rice. If you have them, sprinkle each serving with pomegranate seeds for a garnish.

Uber-Umami, Part II: Beef And Gai Lan with Ground Bean Sauce

So last week, when I posted my recipe for Pork, Tofu and Gai Lan with Ground Bean Sauce, Rose, who is now living in Taipei, (and thus should not have any trouble finding the uber-umami ingredient!) asked if she could successfully substitute chicken or beef in it, as she does not eat pork. With the chicken, I answered it would be a simple matter of using about 1/3 less bean sauce and adding a splash more of the wine, but the beef was another matter.

Beef has a much different flavor than pork, and I have found that I am more successful with exchanging pork and chicken in recipes than pork and beef. There is an inherent sweetness and delicacy of flavor to pork that beef simply does not have, and In my experience, to exchange one for another in a Chinese recipe without changing the seasonings accordingly, is asking for a dish that tastes okay, but not great.

And why make something that just tastes okay? Why not excellence?

So, I thought about it, and since I had another bundle of that absolutely fresh and delectable gai lan that needed cooked up right away, I decided to pull out a piece of top round from the freezer and experiment.

Generally when I make a stir fry of beef and gai lan, I stick very closely to the classical Cantonese formulation, which pairs the two ingredients with umami-laden oyster sauce. Oyster sauce, with its oceanic fragrance, has the distinction of bringing out the deeper flavors of beef and softening them, enhancing the meat with a rich sweetness. I often also use fermented black beans, which with their sharp, musky tang, really bring out the darker flavors of beef, while also counteracting the slight bitterness that resides within the gai lan. The combination is so good that I often find myself reaching for the oyster sauce and fermented beans on a cold winter weeknight when I have beef and gai lan and I need a fast meal that requires little thought.

But, variety is the spice of life, is it not?

So, what is the harm of making up a different recipe for beef and gai lan?

It turns out there is no harm in it at all, it just requires that one reflect on the nature of beef and change the ingredients accordingly.

I changed the aromatics completely. For starters, I switched out the scallions with a thinly sliced onion–about 1/2 cup of very thin slices. These I cooked until they were golden and slightly caramelized, which laid a foundation of sweetness into the dish that beef inherently lacks. I lowered the amount of garlic and raised the amount of ginger; for whatever reason, I prefer the sweetness of ginger with pork and the tingling fire of ginger with beef. I then added to the aromatics two frozen small sliced red Chinese chiles. These were not too hot, but the zing that they brought to the dish really enhanced the strong flavors of the beef, greens and sauce. One could leave them out, but I thought they were a nice addition.

I revamped the marinade, as well. I switched to dark soy sauce, which is great with beef, and raised the amount of ground bean sauce to two heaping teaspoons. This I added to the marinade along with a full teaspoon and a half of chile garlic paste. I lowered the amount of sugar, and kept the Shao Hsing amount the same. Since I used more meat, I added a bit more cornstarch to bind the marinade.

Finally, I also added a small red sweet bell pepper late in the stir fry process so that the slices stayed crisp and brilliant colored. The reason for this was simple–I wanted to add another note of sweetness that was not sugar to the dish, and the contrast between the emerald greens and the scarlet pepper was stunning. One must always remember that the visual appeal of Chinese food is just as important as the flavor, aroma and texture.

How did it turn out?

I asked Zak and Morganna which version they liked better–the traditional one or the new one.

They could not make up their minds.

The ground bean sauce enhanced the natural flavor of the beef to the extent that the sauce, which clung to the meat, greens and peppers tightly, tasted as if it was nothing more than spicy meat juices. It was a very beefy, meaty, savory experience, and I couldn’t decide myself which recipe was superior.

So, Rose–here it is, just for you–my detailed and illustrated answer to your question.

If you get a chance to make it, let me know what you think!

Rose’s Beef And Gai Lan with Ground Bean Sauce

Ingredients:

1 pound top round, trimmed of most fat and cut into thin 1″X1/4″X1/8″ slices

1 teaspoon dark soy sauce (I used Pearl River Bridge Brand)

1 1/2 tablespoons Shao Hsing wine

2 heaping teaspoons ground bean sauce

1 teaspoon chile garlic paste

1/4 teaspoon raw or brown sugar

1 1/2 tablespoons cornstarch

3 tablespoons peanut oil

1 small onion, peeled and sliced thinly (about 1/2-3/4 cup slices)

1 garlic cloves, sliced thinly

2 fresh or frozen red Chinese chiles, sliced thinly on the bias

2″ cube fresh ginger, peeled and sliced thinly

1/2 tablespoon dark soy sauce

2 tablespoons shao hsing wine

1 pound gai lan (Chinese broccoli), thick stems cut on the bias into bite sized pieces, and separated from the leaves

3 tablespoons chicken broth

leaves of the gai lan, cut into rough pieces

1 small red sweet bell pepper, trimmed, cored and cut into 1/4″ thick slices

scant 1/8 teaspoon toasted sesame oil

Method:

Toss beef with the next six ingredients and allow to marinade for at least twenty minutes.

Heat wok on the highest heat setting your stove can manage until a thin thread of smoke wafts upward. Add the peanut oil, and allow to heat up for another thirty seconds. Add the onions and stir and fry until they turn golden–about two minutes. Add the garlic, chiles, and ginger, and stir and fry another thirty seconds or so.

Add the meat, spread it out into one layer and leave it undisturbed on the bottom of the wok to brown for at least one minute. When you can smell and see browning occur, begin stir frying, and cook until half the meat is brown and half is still red. Add the second measure of soy sauce and wine. Keep stir frying until only 1/3 of the beef is red.

Add gai lan stems and stir fry one more minute. Add the chicken broth and the gai lan leaves, and scoop up the meat from the bottom of the wok and lay it atop the leaves, and stir and fry until the leaves brighten in color and just begin to wilt. Add the bell pepper and continue stir frying until the leaves have wilted and become velvety, the meat is brown and the bell pepper is barely cooked.

Remove wok from heat and drizzle with the sesame oil.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.