Internet Service Provider Woes

This is just a quick post to let everyone know I am alive and well, and still eating and cooking, but due to our ISP having outages timed to the exact moments I have to sit down and write–which is usually late at night–I have not been able to post.

However, now that our guest, Theresa, has gone home, and I will have daytime hours in which to write, you can look forward to regular posts returning shortly–so long as the outage times do not change to the daytime.

Which would be just my luck!

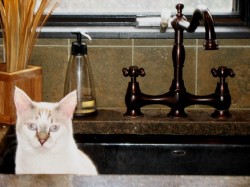

Early Weekend Cat Blogging: Sink Cat

Morganna’s cat, whose name is Lennier, but who gets called Nearble, Mooncalf, Moonie, Schmoo, Schmoobie, Schmoobeast, Moobie and MilkyMoo (all of which he answers to) is a wierd cat who is obsessed with water.

He prefers to drink from sinks. He likes to sit in the bathtub. Sometimes, while there is water in it. When Morganna showers, he cries outside the bathroom, and likes to be let in so he can watch, and then dash into the wet shower after she is done, and sit down. He likes to sit on the edge of the tub when I am in it, and drape his front paws up to his elbows in it and drink the water.

He is truly odd.

The other morning, I came downstairs to behold an odd sight: our beloved Mooncalf sitting in the kitchen sink, which is so deep, only his head was to be seen. He looked like a kid in a bathtub, with only his head sticking out.

When I got close enough to see, he had been having a bath, but hearing me interrupted him and he had to peek out to see who had disturbed him at his ablution.

Silly cat. After taking the pictures, I of course had to chase him out and then re-wash the sink. I haven’t caught him there since, thankfully. Usually he hangs out in the bathroom sinks….

This is getting posted early because we are leaving in the early morning to pick up our dear friend Theresa at the airport in Columbus. She is flying in from Baltimore and will stay in Athens for a long weekend and then fly out Tuesday morning.

For more weekend cat blogging action, check out Kiri and his beloved person, Claire at Eatstuff.

What Is Simple Food?

My thoughts began as I was scrubbing fingerling potatoes last night, in preparation to simmer them.

As I gently scrubbed each thin-skinned little tuber individually, I found myself reflecting upon the idea of simple food.

I realized that I didn’t really know what the words, “simple food” meant. Well, I knew what they meant -to me-, but I was not altogether certain what they meant to other people.

I first encountered this oddity when I was in culinary school. When I would call my mother, she always asked me what I had been cooking–a logical question to ask one’s daughter who spends over eight hours a day in a kitchen, only to come home and spend another two or three in her own kitchen. And I would describe whatever it was I had prepared that had impressed me, such as spinach souffle, or perhaps, poached salmon with sauce remoulade. And she would say to me, “That sounds good, how do you make it?”

And I would always say, “Oh, it is simple, you just….”

The rest of the explanation, which was always sprinkled with French words and phrases such as “brunoise” (a tiny dice), “chinoise mouselline” (a very fine-meshed strainer), “mise en place” (literally, “everything in its place;” refers to having all prep done and organized before the actual cooking starts), and “buerre manie” (a mixture of equal parts butter and flour kneaded together and used as a thickener for sauces and soups), was always lengthy and generally involved more than five steps.

My mother was patient, but she finally said to me, “Your idea of simple and normal people’s idea of simple are two very different things, at least when it comes to the kitchen.”

This puzzled me, in large part, because I spent so much of my time around people to whom it was nothing to whip up a quart of hollandaise sauce within a few minutes, or who thought nothing of putting together masterpieces of pulled or spun sugar threads, and using them as mere decorations for desserts. To my mind, I was explaining the simplest things I had learned, in plain language that anyone could understand.

Slowly, I learned to ditch the French phraseology–no matter how precisely descriptive it was–when I spoke with non-culinarians, and if anyone asked me verbally for a recipe, to make certain to keep it as close to five or fewer steps as I possibly could. Yet, still, when I made these changes, often, I was greeted with amazement as people said, “You do -all of that- to make a sauce?”

When I began teaching classes in Chinese cookery, I realized that the best thing to do when writing down recipes, was to be as precise and detailed as possible, especially when dealing with techniques that are likely to be unfamiliar to my typical students.

When I handed out the recipes, however, students, particularly if they had not had any of my previous classes, would become instantly intimidated.

“Oh my God!” some would exclaim, at glimpsing the heavy packet of recipes and related materials. “This looks too hard–I thought this class was for beginners! I’ll never be able to do any of this!”

Once the packets were passed out and I had finished with my verbal introduction, I found it was necessary to reassure the students carefully that the reason the recipes looked so difficult was because I had described the methods and techniques exhaustively, in order that they would be able to recreate what we did in the classroom at home.

Invariably, once class started and I began explaining, and we all began working together at making bao, spring rolls or simple stir fries, the students agreed that while the recipes themselves were not hard, they appreciated that I had taken the time to write the descriptions so carefully, so that they would have all the details at hand when they went home and tried to replicate them. When I had students return, taking new classes, they always reported back to me that my care had paid off–all of them managed to recreate the dishes at home, exactly. (I am pleased to say that my early exposure to the works of Julia Child probably paid off; unconsciously, when I first started writing recipes, I was emulating her spare, yet detailed descriptions of technique.

So, what is simple food?

I often describe the stir-fried dishes that I present as simple, and to me, they are, but to those who are unfamiliar with the techniques of cutting that are necessary to Chinese cookery, or whose pantry is not filled with fermented beans, soy sauces, chile pastes and sesame oil, these recipes do not qualify as “simple.”

Simple food depends on where you are, who you are, what your tastes and culinary skill levels are, and how patient one is in the kitchen. Some simple foods require little in the way of technique to prepare, but cook for hours, so one should never conflate “simple” food with “quick” food.

Real smoke cooked barbeque requires little in the way of culinary finesse or technique, but it takes hours to days to execute, with the cook standing by to feed wood into the fire, turn the meat, and apply various bastes, rubs, mops and whatnot to the meat as it slowly cooks in indirect heat. So, to those experienced pitmasters who have lived barbeque for years, and to those who recognize that the three main ingredients for good barbeque is meat, wood and time, it is a simple food.

To those who cannot abide the thought of tending a fire for twelve hours, there is nothing simple about it.

I look back at those conversations with my mother when I was in culinary school and shake my head in wonder. I have since gifted my mother with a continuing subscription to Fine Cooking Magazine, a gift which she appreciates more than I ever expected she would. She often cooks from the magazine and when we talk, if a particular article grabbed her attention, or brought up a question for her, she calls and asks me, and we usually have a lively discussion over it. I chose that particular magazine for her for several reasons: one, a lot of the recipes are what she would term, “fancy” food, but many more are pretty simple. It is a technique-heavy publication with emphasis on teaching readers the hows and whys of cookery–lessons they can apply to their own recipes–rather than just presenting recipes. And finally, it is amply illustrated with photographs that illuminate every step of the techniques they present.

I have noticed, interestingly, that my mother’s definition of “simple” has changed since I started her reading Fine Cooking about five years ago.

Though, she still refuses to pepper her descriptions of cooking with any French words or phrases.

Here is a recipe that I promise is the epitome of simple: fingerling potatoes are simmered slowly in water or broth until they are tender, then drained, and cut in half longways. Then, they are allowed to dry thoroughly, and are sauteed in olive oil with shallots, garlic, chile flakes, and fresh basil, and seasoned with salt and pepper.

The shallots are allowed to fry crisp and reddish brown, while the garlic is golden; these crunchy nuggets of sweetness contrast with the melting buttery quality of the potatoes, while the chile and basil add fire and freshness to the entire dish. The results are fragrant, with a wonderful contrast in texture and flavor; I intended this to be a side dish, but it easily could be a simple supper with just a bowl of lentils or bean soup and a salad.

As for the flavors–well, I think this is sort of a southern French kind of dish, though I have no reason to say so. It just tastes that way to me.

Fingerling Potatoes With Golden Garlic and Basil

Ingredients:

1/2 pound fingerling potatoes, well scrubbed (be careful, the skins are thin and fragile, so scrub gently!)

3 tablespoons fruity olive oil

1 large shallot, peeled and thinly sliced

3 large garlic cloves, peeled and minced

1 teaspoon of Aleppo pepper flakes, or regular red chile flakes to taste

freshly ground black pepper to taste

1/4 cup finely chopped fresh basil leaves

salt to taste

Method:

Put the potatoes into a pot, covered well with salted water (or chicken broth for a little extra flavor)and bring to a bare simmer. Simmer them until they are fully tender. (Simmering rather than boiling keeps the skins intact, and makes for extra-creamy potatoes when they are done.) After they are done, drain them, and allow them to dry thoroughly. Cut each into half lengthwise; if any of them are larger than bite sized, cut them in half again cross wise, in order to quarter them.

In a saute pan, heat olive oil over medium high heat. Add shallots and cook, stirring constantly, until they are a medium golden color and are starting to crisp up. Add garlic and Aleppo pepper flakes, then the black pepper, and stir well, continuing to cook until the shallots darken to a reddish color and the garlic is golden and everything is very fragrant. (The oil will take on a reddish hue from the pepper flakes.) Turn down heat to medium low.

Add the potatoes, cut side down, and allow to cook, shaking the pan gently, until a bit of color is taken on the potatoes; they will not crisp up, but will instead the flesh will be tinged a golden reddish color from the oil. Allow them to cook at least three minutes face down to aquire this color. Stir well and continue cooking until the potatoes are well flavored and coated by the oil, shallots and garlic. Add basil, and stir to wilt and combine it with the other ingredients.

Add salt to taste, and serve hot.

Book Review: The Food Substitution Bible

Reviewing books is a passion of mine; reviewing cookbooks and books about food are a particular obsession. This is in large part, because I like to read, write and cook, so three of my favorite activities come together in a delicious synergy.

Though, I have to admit, that generally, I like to read cookbooks or food books that have “stories” to them; you know, the kind of narrative-heavy cookbooks that tell the history and story behind each recipe, and which pour gems of cultural knowledge and wisdom over the reader like a rain of rosewater on a hot summer’s day. And while it is true that I love a good narrative, I am also the child who thought reading the dictionary or encyclopedia was the best fun to have of an afternoon, so it should come as no surprise that I thoroughly enjoyed reading David Joachim’s The Food Substitutions Bible.

It first came to my attention via an email from a very nice public relations person, who wrote to inform me that the book had won an IACP (The International Association of Culinary Professionals) award in the Food Reference Category. When an offered a review copy, I jumped at it, and waited eagerly to set my hands on it.

When it arrived, I was very happy to find that while it contained no stories, it did contain a wealth of worthy information that was well-laid out, sensibly listed, and comprehensive in scope. Substitutions are listed for over 5,000 ingredients, pieces of equipment and cooking techniques in alphabetical form in the main text of the book, while at separate, smaller, but intensely useful section lists ingredient guides and weight and measurement equivalents.

While the main encyclopedic entries were amazingly detailed and interesting on their own, my favorite part was the ingredient guide and measurement equivalents sections at the back of the book. (In the ingredient guide, Joachim focuses special attention on varieties of apples, mushrooms, chiles (fresh and dried), dried beans, lentils, cooking oils, dressing and flavoring oils, flours, and Asian noodles. He gives descriptions of flavors, textures, cooking properties, colors, smoking points and other important characteristics with each entry, and then lists possible substitutions for them. The cooking oils list with the smoking points (the temperature at which the oil will burn) alone is invaluable; but my favorite of all was his list of 29 different varieties of potatoes, grouped by starch content, with descriptions of skin and flesh colors, flavors and textures.

For this Germanic lass who grew up on a steady diet of Irish Cobblers, Kennebec, and Red Bliss among family members who would sit and discuss the finer points of each type as we gobbled them down mashed, boiled and buttered, fried or baked, it was as if I found a kindred spirit in this author who would obsessively list 29 different commercially available types of potatoes in a reference work.

The measurement equivalent tables, or as we called them in culinary school when we had to memorize them–“weights and measures,” is for all the people in the world who cannot convert cups to quarts and quarts to pecks and bushels in their heads as I can. (I was always good at weights and measures in culinary school; this is most likely due to the fact that I was among one of the last generations where such conversions were taught in elementary school. That, and my Grandpa used to quiz me on them mercilessly, because he thought that it was necessary knowledge for anyone who farmed, cooked or preserved food.) They also feature the “weights and measures” problems I -cannot- do in my head: conversions from Imperial measurements (ounces and pounds, like we use in the US) to metric. I was among the first generation to be taught metric measures–and I never remembered the conversions quite right, and I suspect that there are a lot of other folks out there like me, wondering how many grams are in an ounce, and how many litres in a quart.

There are problems with the book. I disagree with some of his substitutions, particularly for Asian ingredients. For example, he suggests substituting fermented black beans, one of my favorite Cantonese flavorings, with black bean sauce, which is sensible, since it is made with fermented black beans. But then,he also suggests substituting them with cooked soybeans flavored with soy sauce. This would absolutely not do at all–the flavor would be nowhere near the same, nor would the texture. Even the level of salt is nowhere equivalent between the two suggestions.

That sent warning bells off in my head, especially when I looked at the amounts he was talking about: the entry for fermented black beans talks about substituting 1/2 cup of them with 1/2 cup of cooked soybeans and 1 tablespoon of soy sauce.

This caused me to blink in surprise, as -no- Chinese recipe that I can think of uses that many fermented black beans! They are a very strong flavoring ingredient, and most recipes use them in amounts ranging from teaspoons to tablespoons–never in increments of a cup!

His primary suggestion for substituting fish sauce is a concoction he calls “Homemade Fish Sauce Substitute,” which consists of soy sauce, anchovy paste or whole anchovy filets, garlic and brown sugar, simmered for ten minutes and then strained. Personally, it sounds simpler to me to just make sure you have fish sauce on hand, and since its availability is widening to even grocery stores in Southeastern Ohio these days, that isn’t as difficult as it once was.

All in all, however, these are minor quibbles with what is essentially a very useful reference work that deserves to be in every serious cook’s kitchen. Joachim may not be absolutely right in every one of his suggestions, but most of the information is both useful and accurate enough to warrant making space for it on your cookbook shelf.

And–at the price of $19.95–it’s a bargain!

Pasta Dharma Talk

I have been craving pasta and noodles like mad recently.

There is a reason for this, which I can’t really go into right now, but it means that for the past week, four out of seven dinners have been pasta or noodles of some form or another. Penne with Meyer lemon cream sauce, Spaghetti with Creamed Eggplant and Walnuts, and then last night, I made a quickie old favorite, Za Jiang Mein, light on the pork and heavy on the tofu, and tonight–well, tonight, I wanted tortellini.

But I didn’t want that stuff from Buitoni. Blech. I wanted real tortellini.

So, that meant I had to break out the old faithful Atlas hand-cranked pasta machine, and have at it.

I figured I would wait for Morganna to come home from school, and we’d make it together, because I knew darned good and well she hasn’t made pasta before.

She was so excited.

And we had great fun. I was going to do a big post on how to make pasta using an Atlas, and show how to fold tortellini, step by step but several things happened.

One, I discovered that it is really hard to simultaneously teach one person how to do this, -and- take pictures. When you are working with fresh pasta, especially, since it wants to dry out immediately and you cannot let it dry out before you wrap the filling into the pasta.

So, I stopped trying to take pictures while the pasta was being made.

Which was a good thing, because the batteries in the camera crapped out anyway. So, I was forced to take them out, stick them in the recharger, and then return to teaching Morganna the art of wrapping pasta dough around tortellini filling.

When the batteries ran out, and I realized I couldn’t teach Morganna and take pictures is when I decided that I just needed to be “in the moment,” and it helped me go with the flow of the evening. Things didn’t work out.

So what?

Sometimes, I think that we all need our plans thwarted now and again. It keeps us humble, and it makes our minds more flexible, when we have to go off script and adapt to changing circumpstances.

Which is how I finally ended up teaching Morganna how to wrap tortellini–I adapted to the fact that she didn’t know much about tortellini, but she sure did know from Chinese food.

It really told me a lot about Morganna’s culinary education when I noticed she was being very clumsy at wrapping the tortellini. Finally, I said, “You know what? Screw how the Italians do it–wrap it like a wonton.”

At which point, Morganna’s fingers flew and out came a perfect wontonellini. I noticed that my fingers were more nimble using that method, because, well, frankly, she and I have wrapped a heck of a lot more wontons than we have tortellini.

I’m sure Marcella Hazan will not mind, and if she does, well, she isn’t likely to come to Ohio to register her complaint, so I don’t care.

And they tasted really, really good, too. The pasta was a simple egg dough wrapped around a filling of shallot, garlic, lacinato kale, prosciutto, parmesgiano-reggiano and ricotta cheese seasoned with a tiny bit of freshly ground nutmeg and black pepper. I sauced it with a tomato-cream sauce that I spiked with some red wine and dried chile flakes and garnished with fresh basil.

It took us three hours to make dinner, but hey–Morganna and I had a hell of a lot of fun. As she said, it was better than math any day.

After dinner, I got the pleasure of sitting down with Morganna and introducing her to one of my favorite films, which was a perfect cap to our zen evening of pasta.

We watched Tampopo, which, well, it is one of those movies that every foodie needs to see. A comedy by director Juzo Itami, Tampopo tells the tale of a woman (named Tampopo, which means, “Dandelion”) who wants to learn to make the best bowl of ramen in the world so that her noodle shop can be the best it can be. She enlists the aid of Goro, a cowboy-hat wearing truck driver, who is a connoisseur of ramen, which can be considered one of the national “fast food” dishes of Japan. An amazing list of memorable and quite amusing characters are woven into the fabric of this film, which speaks to the love of food, and its meaning to all humans in life, and in death.

It is a comedy, that at moments is uproariously funny, but other parts are sad, or poignant.. It is also a restrained sort of love story, which tells more in what it leaves out than in what it shows openly, and there is passion, friendship and folly aplenty as the plot unfurls.

Every time I see the movie, I see something new, and it is particularly satisfying to introduce it to Morganna, who laughed heartily and yet was touched as well.

I think it will end up to be a favorite of hers, as well.

So, that was our evening of zen pasta. We toiled all evening making pasta, filled and shaped it, cooked it, and made sauce for it, then ate it, and it is all gone, now. That is zen. Living in the moment. One moment, there is a pile of tortellini which we spent hours making, and in the blink of an eye–it is gone.

Consumed.

That is the way of all cooking, not just pasta or noodles of course. It seems rather foolish, doesn’t it–to toil so long and hard, for something that is transient, like dinner. jIn the film, Tampopo toils for months to perfect her noodles, which will sell for a few coins, and be eaten within minutes by her customers, but she knows the secret–it gives her satisfaction to please her customers. It makes her heart glow to feed people food that makes them smile, that makes them slow down and actually taste what they are eating.

And besides–here is the truth of it all.

Food only appears to be transient. One minute it is there, and the other minute, it is gone, or it seems to be.

But, of course, it isn’t gone. It is transformed. It is broken down into its component elements and used to build our bodies.

The tortellini I cooked today is even now becoming part of Morganna, Zak and myself. It is used to provide energy for us to live, and yes, in that sense it is consumed, and gone. But some of it is used to rebuild our bodies. To repair our muscles, skin and bones. To make new blood cells, to make new hair growth.

Part of that tortellini will be with us forever.

That is the true zen secret of cooking. What I cook, and transform with my energy, goes into other people and becomes a part of them.

In essence–I am becoming part of them.

And when you look at it that way–it is an illustration of the essential unity of all things–we are all part of each other. The true illusion is that of separation.

Thus concludes my pasta dharma talk for this evening.

Goodnight.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.