Creating Your Own Foolproof Chinese Stir-Fry–Step One: The Main Ingredients

I could subtitle this post:

What to Put in Your Wok.

But, I will refrain.

But, the first thing you need to think about when you set forth to use Barbara’s Rules of Three, is what it is you want for dinner.

Which, in many cases, is determined by what is in the pantry, fridge and freezer. But, some people actually do give forethought to the idea of dinner, where they plan carefully what they want and shop accordingly. I salute such folks, because I am rarely one of them. I let my shopping determine dinner, which is part of why I have such a well-stocked pantry all the time. That way, I can throw something together with whatever looked good at the farmer’s market that week, and it will all be good.

Basically, the first of Barbara’s Rules of Three is this: to construct a simple Chinese stir fry that will serve, along with steamed rice, as a one-dish meal, you need three main ingredients. One protein (vegetable or animal, it matters not to me), and two vegetables.

Why three main ingredients? Well, several reasons.

Protein is good for us and helps fill up the stomach, thus making us feel full.

Vegetables are good for us, and two different vegetables gives a delicious contrast in color, texture, flavor and packs more of a nutritional punch than a single vegetable.

If you think about your putative Chinese recipe as a movie, that makes you, the cook, the director. You have to build your cast, and while your movie will have a large, ensemble cast, it is going to have three main co-stars. Three foods in starring roles, in roles of equal importance, will provide enough variety to keep the diner interested in eating a meal that consists of two dishes: a stir fry and rice. (This makes for less work for the cook and the cleanup crew, which is perfect for weekday night dining.)

Notice I said three ingredients in roles of equal importance. That means that if you use meat in your stir-fry, I suggest that you use less of it than you are wont to do most of the time. This is generally the Chinese way. If you read my recipes, you will note that I often call for a single chicken breast, mixed with vegetables and or tofu, and this will make a one dish meal, with rice, for three to five people.

Now, you don’t have to cook that way. You can use more meat than I do, but I suggest that you use more vegetables than you usually would anyway. Not only are they good for you, but when they are cooked properly in stir fries, they are utterly delicious and they provide a beautiful balance to the dish which is nothing less than artistic. And, as you will learn if you read anything at all about Chinese cuisines, aesthetic considerations matter just as much as flavor and nutrition. (Again, another instance of the magic number three popping up in the philosophy of Chinese food.)

Protein ingredients include any meat , poultry or seafood, (including game, such as venison or rabbit–both are excellent stir-fried) as well as tofu, tempeh and wheat gluten. (If you are making an all vegetable stir fry to accompany a separate protein dish–you can make a three veggie medley. In cases like that, I use shiitake mushrooms, fresh or dried, as the “protein” in the stir fry, even though it isn’t isn’t strictly made of protein.)

Each protein ingredient has a different color, texture and flavor, and a “weight”in the sense of how full they make us feel.

For example, beef is “heavier” than pork to many people, including the Chinese. It is darker, stronger flavored and while it is not necessarily fattier, it does seem to have a different feel to it that just makes it seem richer in many dishes. This of course, depends upon the individual cuts of beef and pork, as well as the individual animals it came from. Some beef is leaner than some pork and vice versa. But, in most cases, the Chinese tend to believe that beef is stronger flavored than pork and heavier on the stomach.

Chicken is lighter in flavor, color and texture than duck. Some fish is considered lighter and less rich than shrimp. And tofu is generally thought to be lighter on the constitution than wheat gluten. Shiitake mushrooms, which while they have a meaty texture and flavor, have no protein at all in them, are the lightest on the stomach of all of these ingredients.

When you choose your protein component, all of these factors need to come into consideration, because they can affect your choice in vegetables. In general, if you choose a light protein, such as chicken or tofu, you can pair them with heavier vegetables without worrying that you are making a dish that will weigh your diners down with too much richness. Chicken and tofu, for example, are delicious when paired with eggplant or mushrooms, both deeply flavored, rich vegetables which tend to soak up the sauce in which they are cooked.

Texture is an important part of Chinese stir fries, and before I start talking about vegetables, I want to talk a little bit about stir frying meats that Americans may not often think of stir frying. Some of these are traditional, and others are not, but all of them are delicious.

Bacon is used in stir fries in the cuisine of Hunan province. One such recipe I featured on this blog, and the technique that it used imparted a very special, chewy-crisp texture to the pork. The bacon was steamed first, and then stir fried in its own fat, then was paired with thinly sliced spiced dry tofu and scallion tops. The bacon was chewy, the tofu was crisped on the edges and the scallions were bathed in the salty-smoky flavor of the bacon, while lending its own delicate onion scent to the entire dish. It was heavenly. Chinese sweet dry sausages, lop cheong, and good ham also are wonderful additions to stir fries; when used in small amounts, these cured meats give an absolutely delectable flavor and interesting texture variations which many Americans may not think of as belonging in Chinese foods. But, of course, they very much do have a place in the varied cuisines of China, and I’d like to see them gain a place in your kitchens, too, because they really add a lot of flavor with the use of a tiny bit of meat.

When I choose vegetables for the stir fry, I like to contrast flavor, color, and texture. Usually, I pick a green vegetable of some sort, and add a yellow, red or white vegetable. Or, I will go with something rich and soft like mushrooms, eggplant or summer squash.

Greens go in most of my stir fries for many reasons, not the least of which is that stir-fried is the only way Zak will eat most greens. So, I choose from whatever is in season from a list that includes, but is by no means restricted to, chard, tatsoi, bok choi, choy sum, gai lan, kale, beet greens, turnip greens, collards, and broccoli rabe. All of these greens have several things in common: they cook up to be at least in part, velvety and tender, they are high in vitamins, they tend to be sweet in flavor, though some do have a bitter edge. Their colors range from pale celadon to jade to grass to forest, and they taste good with a wide variety of meats as well as both tofu and wheat gluten.

Other green vegetables which are not “greens” per se which I include in the category of green vegetables are broccoli, asparagus, celery, snow peas, green beans, Chinese long beans, bitter melon and garden peas. These green vegetables tend to cook up tender-crisp, but only if you go out of your way not to overcook them. There are two ways of doing this.

With broccoli and green beans, one can blanch them in boiling water briefly before stir frying them. This softens the outer parts of the vegetable and makes it more likely to take on the flavors of the ingredients and sauces it is cooked with, and it also shortens the cooking time necessary in the wok considerably. To blanch beans or broccoli florets, simply drop them in water that is at a full rolling boil, stir them, and give them a stir. Let them cook for about two to three minutes–just until the green color deepens and brightens, then drain them immediately, and rinse with cold water to stop the cooking process. Then, let them drain dry, and continue preparing your other ingredients. (Many Cantonese cooks blanch bitter melon briefly in order to remove some of the bitterness–I don’t do it, because I like the strong flavor, and I don’t like the softened texture of the blanched melon much. But, if you cook it, try blanching it sometime and see if you like it.)

The other green vegetables, I simply cook in the wok briefly, near the end of the cooking process. Once blanched, both broccoli and green beans can also be added near the end of cooking a stir fry, so that they retain their crunch, yet still pick up the flavors of the other ingredients.

For the contrasting, non-green vegetable, I choose from a variety of vegetable colors: red, yellow, orange and white, most notably, though purple and brown do show up now and again as well.

Red, yellow or orange bell peppers are an obvious choice that bring crisp sweetness to a stir fry. I add them very late in the cooking process so that they retain their crisp, watery texture, and to keep their sugars intact. If you cook them too long, they become limp, somewhat slimy and their sugars meld with the sauce, bringing more sweetness into the sauce than is necessary. (At least, to my taste.) Carrots are another orange-colored favorite; those faux baby carrots that are merely peeled and carved larger carrots are very convenient in that you needn’t peel them and they are easily sliced into diagonal oval planks, rounds or julienne quickly. Not only that, carrots taste really good stir fried and they can be cooked a bit longer than most other vegetables in a wok, without getting flubbery and sad. Both carrots and bell peppers are great contrasts to the velvety, sauce-hugging greens, as well as the more crisp asparagus and snow peas.

One thing you will learn as you cook more stir fried dishes is that there are different degrees and types of crispness when it comes to vegetables. There is almost an infinite array of textures that in English, we would call “crisp” or “crunchy.” Green beans are chewy-crisp, while bitter melon has a watery, juicy crunch. Bell peppers have a similar texture to the bitter melon which comes from the amount of water they contain, but bell peppers, because of how they are structured, cannot hold their crispness under heat as well as bitter melon. Snow peas are both tender and crisp, and water chestnuts have a nutty crunch to them with a juicy finish similar to a raw apple. Broccoli stalks are tender-crunchy, but the florets are chewier.

White vegetables include the aformentioned fresh water chestnuts (once you try them fresh, you will hate them canned), bean sprouts, jicama (a very good substitute for water chestnuts–juicy with the same texture and a similar, though not as sweet, flavor) daikon and French or English radishes, bamboo shoots, and cucumbers. Bean sprouts are best barely cooked, in my opinion; I tend to put them into the stir fry near the very end and cook them for no more than a minute. Water chestnuts and jicama, (a tuber of Latin American origin) while I cook them slightly longer than bean sprouts, at about two minutes, are still best barely cooked. Both bean sprouts and water chestnuts or jicama are crisp, but, again, in very different ways. The former is very juicy and tender, while still having a distinct crunch, while the latter two are also juicy, but with more of an apple-like bite.

The radishes and bamboo shoots can both be cooked slightly longer, especially if they are cut a bit thicker. Radishes and daikon (also a type of radish, just a really big one), can be cooked tender, and it doesn’t take very long, especially if they are cut thinly. They soak up the sauce they are cooked in, which enhances both the sweet and biting-hot characteristics of these roots. Bamboo shoots have a buttery crunch, if that makes any sense. They are rich in texture, with both a crispness and a bit of a soft chew that is delightful, and goes very well with their sweet, earthy flavor.

Cucumbers can be crisp, if they are cooked only for a few seconds, or they can be cooked longer to give them a soft with a slippery texture that the Chinese find appealing. Americans don’t often think of cooking cucumbers, but we should. They add a subtle astringency to dishes that is refreshing, especially when used in combination with chicken or rich seafood like scallops.

Finally, there are the dark colored vegetables like eggplant, shiitake mushrooms and tree ear fungus. Eggplant and shiitake mushrooms (when they are dried, they are often called Chinese black mushrooms), are both rich, with soft, velvety textures that soak up the flavor of everything they are cooked with. Asian eggplants–the long skinny dark purple, violet or green variety, are so tender and sweet you neither need to peel or salt them to remove bitterness like you must with larger European style eggplants. They soak up everything they are cooked with, including oil, so be aware of this as you cook them. It is part of what makes them so rich in texture and flavor when you eat them. Shiitake are also very soft and spongy, as are other forms of mushrooms, though tree ear fungus–which is sold dry, has no flavor of its own, nor does it soak up flavor–it is merely a texture food. It is squeaky-crunchy mouthfeel that I really like, but I don’t tend to use it as much as I use other vegetables when I am making a simple weeknight dinner.

I’d rather have the flavor and nutritive value instead, so I save the wood ear for more special meals that feature several dishes.

The final thing to discuss when it comes to the main ingredients of your simple Chinese stir fry is the art of cutting them. In the future, I will be writing a series of posts, all heavily illustrated with photographs, and possibly video, on knife skills for the Chinese kitchen.

But for now, suffice to say, that you should attempt to cut your ingredients in analogous shapes and sizes. In other words, if you cut thin, rectangular slices of tofu, you should cut thin ovoid or rectangular slices of cabbage and carrot, if those are your two vegetables. If you cut your chicken into squares, you should endeavor to cut your bell peppers and cabbage into squares as well.

Conversely, if your vegetables are asparagus and bean sprouts, you should cut your protein item into narrow, thin strips to match the shape and size of your vegetables.

This practice is primarily aesthetic; in addition to serving the food in bite sized pieces so that knives, which are akin to weapons, are not necessary at the table, smaller, uniformly shaped pieces of food are considered to be beautiful. It is said that Confucius himself, who set down in his writings the proper ways in which to cook, serve and eat foods, would not sit down to a meal of improperly cut food. If it was not delicious to the eye, it would not be delicious to the tongue, either.

There is a purely practical aspect to cutting your main ingredients carefully as well. When all of your pieces of chicken are the same basic size and shape, they cook more evenly. You won’t end up with tiny pieces of chicken that are overdone, with too large pieces underdone. Learning to cut uniformly is one of the basic techniques that will improve your ability at stir frying immeasurably–before you even touch the wok.

Finally, learn in what order to cook the main ingredients. The protein item always takes longest to cook, so it goes in before the vegetables. Then, ascertain which vegetable will take longer to cook, and put it into the stir fry accordingly. Generally speaking, the harder the vegetable, the longer it takes to cook, though mushrooms, which are not hard at all, can go into the stir fry early, because they do not overcook. Carrots, broccoli, mushrooms, and bamboo shoots take the longest to cook, with green beans coming up in second. Tough greens like collards and kale, and then thicker asparagus come up next.

Vegetables that are very tender need a very short cooking time. Snow peas, sugar snap peas, young greens like baby bok choy, mizuna, radishes, sweet peppers and bean sprouts need very little cooking time. All of these overcook easily and become too soft in no time. I tend to throw them in at the very end of the cooking, so that they just brighten in color, soften slightly and get coated with the sauce, before scraping the entire dish out of the wok and serving it steaming hot.

Next time, we’ll talk about the aromatics–whom I see as being the character actors of your stir fry dish. They are so good at what they do, which is flavoring an entire dish, that they sometimes can overpower the main stars of the show. But, the cook, or director, can deftly manage these strong flavors, and help them give a truly shining performance that supports and improves the aroma and flavor of the main ingredients.

Until then, happy cooking!

I’ll Write a Post Tomorrow.

I tried to write a post today. Really, I did.

But it was utter drivel.

I think it has to do with trying to type with a finger that was pierced by a sewing machine needle last night.

Or maybe it could be the lingering headache I have from a fall I took this morning.

I am going to bed.

Because tomorrow is another day.

Creating Your Own Foolproof Chinese Stir Fry: Introducing Barbara’s Rules of Three

I’ve been thinking a lot recently, in large part, because with a nursing infant in my lap, I do a lot of sitting still. And since I am not particularly good at sitting still and doing nothing, I let my brain wander as it will. Some part of my person, at least, gets to move, and these days, it has been my thoughts.

And I have been thinking a lot on cooking in general, and Chinese cooking in specific. And even more specific, the art of stir frying, and how to simplify it further than I have before, without losing the essential Chinese nature of it.

One of my goals in presenting my thoughts on Chinese cookery is to get readers comfortable enough in the techniques that are fundamental to the Chinese kitchen that they can release themselves from reliance upon recipes and learn how to create their own dishes. My reasoning for this is simple: cuisines are continually in flux, and they evolve over time. With each cook who learns a style of cookery and takes it beyond the cookbook and begins to play riffs based upon established themes, that cuisine grows. Also, I think that the best food in the world often comes from people who are not using a recipe at all, but are cooking from the heart, with what they have on hand, and with the equipment they have in the kitchen.

In writing my series of three posts on the art of stir frying and my introductions to basic ingredients of the Chinese pantry, I have given readers some tools to make their stir-fried dishes better than they were before, but I want to give them a leg up to the next level of cooking.

I want readers to leave the recipes behind and cook from their hearts.

Which is where my “Rules of Three” come into play. They arose from me sitting and feeding Kat while in my head, mulling over and deconstructing the ingredients and methods of Chinese stir frying, then codifying them into a handy-dandy, easy to remember, yet flexible set of guidelines.

Three is a magic number. Yes it is, it’s a magic number. We all know that–at least, all of us Americans of a certain age who grew up watching Schoolhouse Rock know that.

And since it is such a magic number, it should come to no surprise to you that I have found it to be a useful mnemonic to help folks learn how to create their own Chinese style stir-fries that not only taste good, but are easy to make.

And the beauty of my “Rules of Three” is this: once a cook has worked with them and started making some pretty darned awesome stir-fries, she can start meddling with the formula, and add a little bit of this or that. The magical symmetry of the number three will be lost, but that is the way of all rules; when they become constricting, they are modified or discarded, and the world is better for it.

So don’t look at these rules as cast in iron or carved in stone; I am no culinary Moses, bringing wisdom down from on high. I see my Rules of Three as training wheels for a wok; they are nothing but tools to help beginners get their balance before riding off on their own creativity. My goal is to have readers use these rules to loose themselves from the constraints of cookbooks, and create stir fry dishes which are uniquely their own, but which still taste authentically Chinese–which is what most Chinese and Chinese American home cooks do every day.

The “Rules of Three” are simple. Essentially, one can gather the basic components of a simple Chinese stir fry into groups of three. And, in order to make it even more special, there are three main basic components to a simple Chinese stir fry. So that adds up to three groups of three ingredients.

There is also a fourth component to a simple Chinese stir fry, which messes with the magical symmetry of my theory, but that is fine, since this fourth component serves a supportive function, and oddly enough, comes in three parts, which makes brings back to our magical mnemonic number.

The three main components to a simple Chinese stir fry are the main ingredients, the aromatics and the condiments. The fourth component is the supporting ingredients which serve purely structural and functional roles in the recipe.

So, in a nutshell, Barbara’s “Rules of Three” for making simple Chinese stir fries are thus:

Take three main ingredients.

Add three aromatics.

Add three condiments.

Apply heat and three supporting ingredients.

Voila!

You have a simple Chinese stir fry that tastes great, and didn’t require a recipe.

In the next few days, I will be elaborating on each step of this process, outlining in detail the main ingredients, aromatics, condiments and support ingredients, and at the end, will present a vegetarian recipe Morganna made up for dinner the other night using these principles.

When I am done with this series, hopefully, we will have a very useful tool for cooks, both beginners and advanced, to use when they step into the kitchen with the intention of firing up the wok and whipping up a fast, simple dinner that tastes great yet doesn’t require delving into a cookbook.

Stir Fry Technique III: Ten Steps to Better Tofu From a Wok

Following my post Stir Fry Technique: Ten Steps to Better Wok Cookery, I wrote a post specifically dealing with chicken, Stir Fry Technique II: Ten Steps to Better Chicken From a Wok. When I wrote that post, there were many requests for a similar post about tofu, so finally, after much trial and error, testing and tasting, here it is. (With a big thank you to Dan for the many fine photographs he took for this post last night when he showed up around dinnertime last night. He’s always good-natured about being drafted into my blogging schemes, and besides, he then gets to eat dinner, which makes it all good all the way around.)

Before we dive into step one, I want to refer future readers to the introduction to this post, written yesterday: Stir Frying Tofu Part I: Choose Your Tofu Wisely. Carefully following the suggestions in this post will go a long way towards ensuring success in stir frying tofu. The key is to get tofu that is as firm as possible, and to avoid any silken tofu for stir frying, even if it says on the package that it is “extra firm” and suitable for stir frying. While one -can- use it for stir frying, it is difficult to do, and the likely result is a mushed up mess in the middle of a wok.

That said, note that the example I provide here was made with Spring Creek brand tofu which is the firmest Chinese-style tofu I have ever used. It does not require any preparation other than slicing and marinating before stir frying. However, other brands do require a ylittle more work to make them foolproof in the wok. More simple yet is the spiced dry tofu which does not even require marination, and in fact, is pretty much a “slice and go” sort of product. If you are using spiced dry tofu, you will not need to follow every step of this guide, and in fact, are working with a product that is even easier to stir fry than meat. My advice is that if you can find spiced dry tofu, get it and try it out. If you like the flavor and texture, use it as your default tofu for stir-frying, especially if you want to create dinner in a hurry.

Step One: Determine if your tofu will work as is or if it needs to be pressed. If it requires pressing, press it.

The easiest way to do this is to slice a piece about 1/2″ thick off the narrow side of the tofu and pick it up between thumb and forefinger and give it a gentle, but firm shake. If it holds together fine, you are good to go. If it cracks, tears, falls apart of squishes, you need to press a bit more water out of it before it is ready to stand up to the rigors of stir frying.

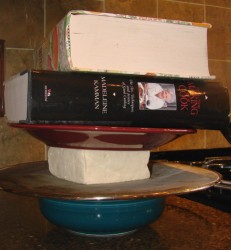

If your tofu needs to be pressed, start this about five hours or so before dinner. (Or, do it the night before.) Unwrap your tofu and drain out all the water from the package. Set the block(s) of tofu on a rack or screen of some sort–I use a splatter shield, as illustrated to the right–over a bowl. Put a plate flat on top of the tofu, then set heavy objects like one of those food service cans of green beans that you see in school cafeteria kitchens, or a couple of doorstop-sized cookbooks or a clean (!) cinderblock on top of the plate. Allow the tofu to be squeezed for at least five hours, though you can, if you have room for it, stuff the whole kit and kaboodle into a fridge for overnight pressing.

Once that is done, disassemble your impromptu tofu press and proceed onto the next step.

Step Two: Slice and marinate your tofu.

As with all other stir fry ingredients, you want your tofu to be cut into uniform sizes and shapes, for several reasons. The primary reason is that you want them to cook evenly in the wok. There is nothing worse than a stir fry where half of the ingredients are overcooked and the other half undercooked, because they were not cut evenly. The second, and equally important reason from a Chinese perspective, is aesthetic–foods that are evenly cut are more pleasing to the eye and appetite.

My guidelines for cutting tofu that is going to be cooked in a wok delve more into thickness than width or height. The reason for this is because if you cut the tofu too thinly, it is more likely to break apart as you start stirring it in the wok. If you cut it too thickly, however, it is not going to cook as well on the inside as it does on the outside.

This rule applies only to fresh tofu; spiced dry tofu can be cut quite thin, because it is so compressed before you even bring it home from the store. I cut spiced dry tofu quite thin–around 1/8″ inch, typically, and unless I cook it for a long time, it does not become overcooked.

I like to cut fresh tofu to a thickness of about 1/2 inch. I do this as illustrated by setting the tofu block upright on the board, with the square top upwards. I then cut 1/2 inch thick slices across the block. Then, I cut each slice in half, into a flat square–as seen in the first photograph for this post. For more bite-sized pieces, one can also take each of those squares, and cut them on the diagonal into triangles–this shape is very pretty, especially when cooked with greens which are amorphous in shape, and fresh or rehydrated shiitake mushroom caps which have been cut into halves.

After the fresh tofu is cut, it needs to be marinated. For this tofu recipe, I used a mixture of dark soy sauce and Shao Hsing wine. One could also use light soy sauce, tamari soy sauce or fish sauce in the marinade, but I chose dark soy sauce because not only is it salty, it has a hint of sweetness in it because it has caramel or molasses in it, and it gives a fantastic deep, rich color to the tofu.

Unlike most meats, one cannot add cornstarch to the marinade and expect it to stick evenly to the tofu. I find that if I don’t put the tofu into a dish large enough to contain it all in one layer, I end up having to rotate the tofu slices from the bottom to the top. It is best just to use a shallow dish, and enough marinade to cover the bottom of the dish. After the tofu has marinated for fifteen minutes on one side, it is a simple matter to turn it over, and allow the top to come into contact with the marinade. This allows the marinade to evenly penetrate all sides of the tofu, and will result in a better color for it when it is cooked.

Step Three: When you are ready to stir fry, remove the tofu from the marinade, and either dredge it in cornstarch or pat it dry with paper towels.

The purpose of either of these actions is twofold. One, it keeps the wok from sputtering and spewing splatters of hot oil all over you when the liquid marinade hits the hot wok. Two, it helps develop a rich brown outer surface on the cooked tofu.

Which do I mean for you to do? Well, that depends on the final outer texture you want your tofu to have. In both cases, you will end up with a browned outside layer, but if you use a dredge of cornstarch to dry the tofu, you will end up with an interesting, soft, slippery outer layer. If you simply pat the tofu dry with paper towels, it will develop a chewy, lightly crispy outer layer. So, it is all up to you. Do one or the other, or else suffer a splatter of hot oil up and down your forearms which can hurt enough to make you want to swear off stir frying tofu forever.

One thing, though–if you don’t use the cornstarch on the tofu, add a little bit of it to the marinade left in the dish. This you can use to thicken the sauce later in the cooking process. If you coat the tofu with cornstarch, you can skip that step–there will be enough cornstarch in the wok from the tofu alone to thicken the sauce otherwise.

Step Four: Heat your wok until it smokes, then add oil. Then, add all of your aromatic ingredients except garlic. Cook the aromatics until they are about half done.

This part is the same as cooking anything in the wok, except for a few points. You can use a tiny bit less oil in cooking tofu than you would use in cooking meat, but not much less. I usually cut my oil down by a tablespoon for tofu, so I go from 3-4 tablespoons to 2-3.

I leave out the garlic until after the tofu is in the wok for several reasons, most of which has to do with how long it takes the surface of the tofu to brown. (It takes longer than thinly sliced meats.) By the time the tofu starts browning, any garlic that is in the wok, against the metal surface, will brown. That is why I let the tofu itself shield the garlic, while the tougher aromatics like onions, scallions, ginger, chile and fermented black beans cook all around, under and on top of the tofu.

Step Five: Gently place the tofu into a single layer on the bottom and lower sides of the wok. Then spread the uncooked garlic over the tofu. Then leave the tofu to sit in the wok, untouched, until it browns on the bottom.

What I try to do is scoot the aromatics up near the edges of the wok, out of the way. If a few onions or bits of ginger get left behind, don’t worry overmuch about it. Then, I carefully set each piece of tofu in place BY HAND. This means, you have to be careful, because you are setting food onto a very hot surface. Just be careful. But don’t dump the tofu into the wok the way you do meat. If you do that and then try to move the tofu into a single layer on the wok in order to get it to brown, you will likely break it up, and there goes your pretty, perfectly cut pieces.

Once you have the tofu set out into a single layer, scrape or scoop your aromatics down around and over the tofu. This adds flavor to the tofu, as well as keeps your aromatics cooking. Putting all of the tofu into the wok at one time lowers the temperature a bit, but if you have your flame on high, it will rise quickly enough. But it is lowered enough to keep from burning the aromatics while the tofu is busy browning.

Sprinkle the garlic over the tofu, and let it sit in the hot wok gently warming, shielded from the very hot metal by the tofu.

How long does it take the tofu to brown? About a minute or two, usually. You can smell it and see it–the edges will start to look brown. Or, you can scrape up a piece with your wok spatula and peek under it. If it is still pale, or worse, if it sticks, it is still working on browning. Lay it back down and let it go back to work, while you work hard at leaving it alone.

Step Six: Gently flip over the tofu, and spread it into a single layer, then leave it alone to brown the other side.

This is probably the most difficult part of the entire procedure, and this is where you are most likely to break up your tofu. You must “have the courage of your convictions” as Julia Child would say, and sliding your shovel under two or three pieces of tofu at a time, give a quick flip of the wrist and turn them in one move, then gently slide them in place so they have as full contact with the hot metal of the wok as possible. Then, you have to repeat the action as many times as necessary to do every piece of tofu.

The browning of the tofu toughens it considerably, and makes it more able to withstand rigorous stirring. But in its half-cooked state, it is particularly vulnerable to breaking. So, turn it this time in as few movements as possible, then settle it back down on the bottom of the wok and allow it to brown on the second side, which will again take a minute or two of undisturbed cooking.

As you can see, this method of cooking tofu results in a deeply browned, flavorful exterior, which is both aesthetically pleasing to look at as well as having a good texture. The dark soy sauce will make a darker crust, but while a lighter soy sauce creates a paler result it is still pretty, and very tasty as well.

Step Seven: Once the tofu is cooked on the second side, flip it over, then add any additional vegetable ingredients in the order in which they are meant to cook, from those that take longest to cook, to those which quick quickly.

So, flip all of the tofu back over, and start adding other ingredients. At this point in time, now that both sides of the tofu are browned, you may more vigorously stir fry than you did in the beginning, because browning toughens up the tofu. It is now able to withstand less gentle treatment, so it is at this point you pick up the pace and cook like you are on Iron Chef.

When you first start trying these techniques for cooking tofu, I suggest that you limit the number of vegetables you add to the mixture to one or two., for the sake of simplicity.

In the recipe I used to illustrate this post, I only added kale. (The recipe is a simplified version of my tofu and chard recipe here: I left out the chicken, the honey, the light soy sauce, the chile and replaced the sesame oil with oyster sauce. ) If you wanted to add a second vegetable to this dish, I would consider something crispy, like carrots, in which case, you would add the carrots first, and then add the kale after that.

When you are more adept at stir frying tofu, feel free to add as many different vegetables as you like.

Step Eight: Deglaze the wok, and add marinade mixture to the wok in order to begin making the sauce.

Add whatever liquid you want to the wok to deglaze any browned bits stuck to its surface. In this case, I used wine, but one could use chicken stock or vegetable broth just as easily. If you are cooking greens with this dish, as I did, deglaze the pan first, pouring in the liquid, and scraping and turning the food, stirring in the browned bits that you scrape off the sides of the wok. Then, add the greens on top of the wok which is now steaming from the liquid which is boiling away. Add a little more of your deglazing liquid, and stir the greens, until they begin to wilt.

Step Nine: Add the marinade ingredients to thicken the sauce and give it color.

This step is simple–if you didn’t use cornstarch with the tofu, you add it now, dissolved into the marinade ingredients, and stir the contents of the wok to allow the sauce to thicken. If you dredged the tofu in cornstarch, you just add the unadorned marinade ingredients and stir, while the sauce thickens and boils.

Step Ten: Add whatever finishing touches you want to the dish, stir and remove from the heat, and serve.

This refers to any final additions to the sauce, such as sesame oil or oyster sauce, which are stirred in at the last minute, or to any garnish such as sliced scallion tops, chopped cilantro or crushed peanuts. Just stir them in, turn off the heat and scrape the finished dish out of the wok and into a serving platter or bowl.

That is all there is to cooking fresh tofu in a wok. It is really simple, once you get the knack of it. And once you have a grip on the technique, you will find yourself wanting to make numerous tofu and vegetable dishes to suit every mood and palate. You will think of new marinades and sauces to try to make an endless number of variations on the simple dish of stir fried tofu.

There are other, additional techniques one can use to change the texture of your tofu before stir frying it. You can freeze it first, which gives it a chewier, spongier texture that soaks up marinades and sauces very well. Or, you can deep fry it, which makes it crisp on the outside and chewy on the inside. Or, you can pan fry it, then cut pockets into the tofu, stuff it with a filling and then stir fry it.

The possibilities are nearly endless.

I hope that this little guide has helped answer some questions, and opened doors for folks who have had troubles cooking tofu in the past. Personally, it is one of my favorite foods, and I hope that by posting about it, I have inspired others to jump into cooking it and experimenting with it.

Stir Frying Tofu Part I: Choose Your Tofu Wisely

Finally, I am getting around to writing about how to successfully stir fry tofu. But before I launch into my Ten Steps to Better Tofu from a Wok post, let’s talk more generally about our main ingredient.

High in protein and low in fat, tofu is an ancient vegetarian food product made from ground up soybeans which are pressed to extract their juice. The juice is then coagulated by the addition of an agent such as nigari, (magnesium chloride, which is traditionally obtained in Japan from evaporated sea water) or gypsum (calcium sulfate, which adds dietary calcium to Chinese style tofu), which causes it to form into cheese-like curds that are then pressed into blocks. Originating in China over 2,000 years ago, where it is called doufu, there are many theories as to how it was first created. One theory, called “The Accidental Coagulation Theory,” is one I find most likely; it states that the probable origin of tofu came about when a cook seasoned a soup made of pureed soybeans with unrefined sea salt that contained nigari. The soup then coagulated, and the cook, tasting the unexpected result, found it to his or her liking. Experimentation then began, which has resulted in the myriad forms we find tofu today.

Fresh tofu can be silky soft, like a custard, or firm, almost like feta cheese. It can marinated to flavor it, and pressed to remove most of the water; this results in a very chewy, firm texture similar to meat that is called “spiced dry tofu.” In any form, it can be fermented, and further marinated, often in garlic and chilies. Fermented soft tofu is sold in jars filled with chilies, garlic and fermented black soybeans; the scent of it is strong, and is very savory, like many aged cheeses. This sort of fermented tofu is used much like a condiment or relish and is not used as a main dish.Pressed dry tofu can also be fermented; sliced thinly and stir fried, it adds a very unique flavor to a stir fry, but the fragrance is very stinky, and not to everyone’s liking. (Zak once mistakenly brought home fermented pressed tofu for me to stir fry, and I did. He and Morganna did not like the taste of it, and -really- hated the smell of it. I rather liked it, but I have refrained from cooking it again out of respect for my family’s wish that our home not smell like fermented gym shorts.)

Tofu comes in even more forms than that, but these are the styles of tofu most American cooks will run across in their average Asian market or mainstream grocery store, and it is from these varieties that they will have to choose when it comes time to buy some tofu to stir fry. And, it is often because of the many different types of tofu found on the market that many new cooks end up with stir-fried tofu that turns into mush in the wok; it is hard for a cook to know what to buy in order to maximize their chance at success.

Pictured above and below are a group of various types and brands of tofu which are suitable for stir frying to greater and lesser degrees. Each of them can be stir fried, but some are easier to use than others, especially for cooks new to using a wok to cook tofu. Let’s examine each one in depth and discuss the pros and cons of each variety when it comes to stir frying, because I am very much of the belief that if you get the right kind of tofu, you cannot help but make a delicious stir fry.

Then in the next post, we will talk about how to go about stir frying tofu once you bring it home.

In the photograph to the left, let us first look at the fresh tofu. This tofu is what most people think about when they think about tofu; it is unfermented and minimally processed. It is white, and is marketed in blocks that weigh about eight ounces each that are packed in water to maintain moistness and freshness. It comes in various textures; Chinese style tofu such as the “Spring Creek Organic” brand in the upper left corner, is extra firm, and is frankly, the best tofu I have ever had, bar none. It is made from Ohio-grown soybeans about ninety miles from here, in Spencer, West Virginia by our hippy hillbilly friends, and it is awesome. I can cook it straight from the package in a wok with minimal breakage, and it cooks up to a great texture and flavor.

To the right of it, you see a brand that is commonly seen in Asian markets, House Foods. This fresh tofu comes in all textures, from extra soft, soft, medium, firm and extra firm. (They also make an organic version of their products, which is very good.) While the flavor is not as good as Spring Creek, and the firmness level of their extra firm is still softer, it is still very, very good, and I have had no problems achieving good results in stir frying it.

Other good brands of fresh tofu to use for stir frying include Nasoya and White Wave tofu. In all brands of fresh tofu, I suggest that you buy firm or extra firm, in order to achieve the best results when stir frying. Even so, with some tofu brands, the extra firm will require some extra work to keep it together well enough in order to stir fry it successfully.

One type of fresh tofu I do not recommend for stir frying, even though the package specifically states that it is good for that purpose (it is on the right in the picture), is extra firm silken tofu. Mori Nu puts out very tasty extra firm silken tofu in aseptic packages that do not require refrigeration. I have used it successfully in hot and sour soup and braised in ma po tofu (though I prefer the firmer texture of Spring Creek for the latter purpose), but there is no way to stir fry it without it breaking up. I even have to be careful stirring hot and sour soup after adding this tofu, so I can only imagine what evil things would happen in my wok if I tried to stir fry it. (Can we say undifferentiated mush, everyone? Icky!)

In the center of the photographs is the easiest form of tofu to stir fry of all: spiced dry tofu. Made by Water Lilies Foods in New York, and widely available in Asian markets across the country, this tofu has been simmered in a spiced broth, then pressed to remove most of the water, giving it a very chewy, firm and dry texture that is quite meaty. It comes in thick or thin blocks (the purple package in the center of the photograph is the thick blocked variety; the green package that is turned away from the camera to show the tofu itself in the foreground is the thin block variety) and it also comes in thin strips. It also is available fermented, but there are no photographs of that variety, alas, because as I mentioned before, I am disallowed from bringing it into the house.

Spiced dry tofu is the absolute easiest, most foolproof tofu to stir fry. You slice it and go. You don’t need to marinate it, add cornstarch to it, press out excess water or anything. You just slice it thick or thin, straight or on the diagonal, and it is ready to cook. I highly suggest seeking this tofu out if you have tried to stir fry tofu in the past and have only gotten scrambled up, broken glop for your trouble. You will not have that problem with this tofu.

Finally, there is a form of spiced dry tofu imported by Wen Foods which I have just started using in stir fried dishes. In English it is labeled as a tofu chile terrine, but what it is is spiced dry tofu that has been thinly sliced and marinated in ground chilies, then stacked back together into blocks. I cut the thin blocks into strips and stir fry them with onions, black beans, garlic and greens for a delicious, spicy, salty dish that forces the diner to eat a lot of rice.

There are many other sorts of tofu on the market, and among them are some soft varieties that can be used for stir frying. However, when it comes to the softer types of tofu, one always has to take extra steps in preparing them in order to stir fry them, including sometimes deep frying, freezing, pressing or pan frying them first. In my experience, if you don’t want to take the time, trouble and effort of these techniques, it pays for you to seek out the firmest types of tofu available and use them in your stir fries. It is the path of least resistance, and is the way to go when it comes making a quick, nutritious and delicious dinner on a weeknight.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.