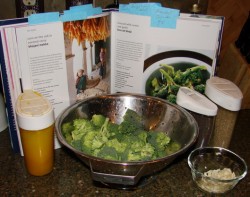

From India’s Vegetarian Cooking:Broccoli With Five Spices

I know that I just wrote about a stir-fried recipe from the eastern region of India that featured whole spices.

Well, that recipe came from the eastern region of India, and this one, while it uses the same basic technique–stir frying, and similar ingredients–whole spices, is from the west, in Bengal, and it results in a completely different flavor.

Because it requires five different whole spices, one might consider it to be a bit more “advanced” than the first recipe I posted from Monisha Bharadwaj’s India’s Vegetarian Cooking, but really, the method of the recipe is completely comparable.

The result, however, is completely different.

The five whole spices are all seeds: cumin, fenugreek, kalonji (also known as nigella), fennel and mustard. Toasted in sunflower, canola or peanut oil until they sizzle, darken and pop, they are then joined by powdered turmeric and chile.

The aroma is incredible. Cumin, of course, has the familiar musky-smoky scent, which is always complemented by the nutty sharpness of the mustard seeds which pop and jump from the pan in frisky arcs. Joined by the freshly-mown hay odor of fenugreek and the sharp onion tang of kalonji is the honey-sweet herbal fragrance of fennel.

All toasted together, these seeds perfumed the kitchen with a voluptuous richness that is hard to understand until it is experienced.

Bharadwaj swears that any vegetable can be stir fried in this way and taste amazing; I cannot help but think she must be right.

This spice mixture elevated plain old healthy broccoli into a dish fit for a decadent libertine. I felt sinful while eating it, which seldom happens unless cream, butter, truffles, chocolate or champagne are involved. I have certainly never felt that way about broccoli in my life.

I highly recommend that folks give this easy recipe a go, and see what happens. I cannot wait to try it on eggplant, collard greens or delicata squash.

Now, I just need to test a recipe from the southern region of India. Look for that post soon!

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons canola, sunflower or peanut oil

1/2 teaspoon cumin seeds

1/2 teaspoon fennel seeds

1/2 teaspoon kalonji (nigella) seeds

1/2 teaspoon fenugreek seeds

1/2 teaspoon black mustard seeds

1 teaspoon turmeric

1 teaspoon ground cayenne

1 pound broccoli, cut into small florets

juice of one small lemon

salt to taste

Method:

Heat oil in a heavy bottomed frying pan or wok until it is nearly smoking.

Add whole spices, and stirring, toast them in the oil until they begin to sizzle, darken and the mustard seeds pop. When this occurs, add the turmeric and cayenne, and stir to combine.

Add broccoli, and cook, stirring, until it brightens. Some browned spots on the stems and flowers is fine; in fact the browning adds a delicious smoky flavor to the vegetable. Add the lemon juice and allow it to steam the broccoli until it is done.

Sprinkle with salt to taste and serve immediately.

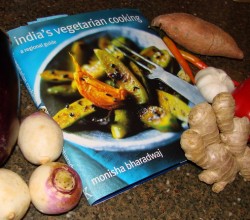

From India’s Vegetarian Cooking: Spiced Turnips

Turnips are not one of the first vegetables most Americans would think of when they think about Indian food. Turnips are a cold weather root vegetable which I always think of as a staple of the winter kitchen.

Winter is not a season that I generally associate with India.

Of course that is silly and wrong-headed of me. The Himalaya Mountains stand in the northern part of the country, and there is plenty of snow and cold weather in and around them. Turnips grow in the northern regions of India, particularly Kashmir, and are used commonly in stir-fried dishes and relishes, but also in curries.

When I saw this recipe in Monisha Bharadwaj’s book India’s Vegetarian Cooking I knew I had to make it, because I adore, absolutely love and am thoroughly enthralled by turnips. They are wonderfully juicy and crunchy when raw, sweet and with a spicy bite. Cooked, they are as smooth as butter, with a honey-kissed flavor. As a kid, I only ate them raw, but as now that I have officially grown up, I like them any way they are put before me, so long as they are not just boiled plain until they fall apart into a mushy, watery ooze.

Just as I found the broccoli recipe I tried from the book to be simple and delicious, so was this curried turnip dish. I did modify it in two ways, however. First of all, it called for two fresh ripe tomatoes. Being as it is winter here, and there are no fresh tomatoes worth eating to speak of, I simply substituted the fresh ones for a fourteen ounce can of Muir Glen Diced Fire Roasted Tomatoes. And second, I added a few whole mustard seeds to the spices, with the rationale that since mustard and turnips are related, the flavors would go well together. Happily, my assumption turned out to be correct.

The first night we had them, the turnips were paired with a variation of my keema sookh recipe that I made with peas and potatoes added to the keema. The leftover turnips we ended up eating as part of a vegetarian meal that included masoor dal palak and mattar masala (recipe forthcoming) with steamed basmati rice. It was a lovely combination of contrasting colors, flavors and textures on the plate. The sour tang from the tomatoes and the smoky flavor of the cumin perfectly complemented the delicate sweetness of the creamy-textured turnips.

I think that this is another ideal beginner’s Indian recipe, because the list of ingredients is relatively short and the techniques used are quite easy.

The more I cook from this book the more I like it, though I think that her explanations on cooking techniques could do with a bit more detail and precision of language, especially for the sake of beginning cooks. When I present the recipes here, I have added a great deal more clarity to the methods so as to make them perfectly understandable by cooks unfamiliar with Indian foods and cookery.

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons canola oil

1 large onion, thinly sliced

1/2 teaspoon fresh ginger, finely chopped, then ground to a paste

1/2 teaspoon fresh garlic, finely chopped, then ground to a paste

2 fresh green chilies, thinly sliced

1 teaspoon whole mustard seeds

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1 teaspoon ground coriander

1 14 ounce can Muir Glen Fire Roasted Diced Tomatoes

1/2 teaspoon turmeric

2/3 cup water

10 ounces fresh turnips, peeled and diced (2 cups or so)

1/2 teaspoon brown or raw sugar

salt to taste

1/2 cup firmly packed fresh cilantro leaves, roughly chopped

Method:

Heat the oil in a heavy-bottomed pot and fry the onions until they are golden. Add the ginger and garlic paste, the chilies and the fresh mustard seeds and keep cooking and stirring, until the mustard seeds pop and the onions are dark reddish brown.

Sprinkle the ground cumin and coriander over the onions, and stir and fry for another thirty seconds, or until the fragrance of these spices is released. Pour in the tomatoes, the turmeric and water, and stir to thoroughly combine.

Add the turnips, and cover. Bring to a boil, then turn down to a simmer, and cook until the turnips are softened, but are not falling apart. (You may need to add water if it all simmers away before your turnips are done–it depends on the age of your turnips. Older, woodier roots take longer to cook than the younger, fresh crisp ones.)

Sprinkle with the sugar and add salt to taste.

Stir in the cilantro and serve immediately.

From India’s Vegetarian Cooking: Broccoli with Cumin and Garlic

One of the barriers many Americans have to trying to learn to cook Indian food is the feeling that it is too complex, difficult and requires way too many ingredients, especially spices.

That many Indian recipes require more than five or six spices or aromatics is sometimes true. That there are unfamiliar techniques involved in Indian cooking, such as deeply browning onions, and then grinding them into a paste, is also sometimes true. That some of the cooking methods and times are long and slow is also true.

I know that at one time, Indian cookery intimidated me because of its lengthy ingredients lists, its many ways of treating spices and its unfamiliar terminology. However, I took into account that at one time, Chinese cookery had also seemed elusively difficult, with long lists of new ingredients, new, exacting techniques and new terminology which I did not understand, yet, I eventually learned to be competent at recreating dishes I had tasted from the home kitchens of friends and employers. I realized that at first, any new culinary undertaking can be daunting, and that is no reason not to try it.

Besides, over a number of years, I have learned every Indian recipe is not necessarily complex, difficult or involves a miles-long ingredients list. In fact, quite a few of them are really simple, yet result in fantastic flavors and textures that make a great addition to any cook’s repretoire.

This recipe for Broccoli with Cumin and Garlic, from Monisha Bharadwaj’s India’s Vegetarian Cooking: A Regional Guide is one such simple recipe. Although she notes that traditionally, cauliflower is cooked in this way, broccoli is becoming more and more available and used as a vegetable in India, and is used in many of the same recipes as its pale-flowered cousin.

This recipe comes from the western region of India which encompasses the states of Rajastan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Madhya Pradesh. Bharadwaj suggests eating it with rotis, but I had it with dal and rice and it was lovely.

Broccoli With Cumin and Garlic

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons peanut, sunflower or canola oil (Bharadwaj specifies sunflower, I used peanut because that is what I had)

1/2 teaspoon mustard seeds

1/2 teaspoon cumin seeds

pinch asafoetida

3 cloves garlic, minced (Bharadwaj used 2, I used 3 because I love garlic)

1/2 teaspoon ground turmeric

10 ounces broccoli, cut into florets–about 5 or 6 cups

salt to taste

water as needed

Method:

Heat the oil over medium-high heat in a heavy-bottomed frying pan or wok. Add mustard seeds and toast, stirring. When they begin to pop like popcorn, (they do, really–its cool!) add the cumin seeds and asafoetida. Stir, and as soon as the cumin seeds begin to darken visibly, add the garlic and turmeric. Give another stir to incorporate the turmeric, and then immediately add the broccoli and sprinkle with salt. (I used a gentle pinch of salt. Less is definately more here.)

Stir a few times, to get the flavored oil all over the broccoli, then add a couple of tablespoons of water to the pan and loosely cover to allow broccoli to steam. When the broccoli is nearly done to your liking (it should be bright green and tender-crisp), lift the lid, turn the heat up to high and boil off the rest of the water (if there is any left). Stir one more time to get all of the garlic bits and spices on the broccoli and serve immediately, still piping hot.

Note: If your pan is thinner bottomed than mine, please turn your heat down to medium–you want the garlic to be lightly golden brown, not burned dark brown or black. That is the only trick to this dish–otherwise it is simple. Also, if you want to make this dish, but do not want to get three spices–cumin seeds, mustard seeds and asafoetida, then leave out the asafoetida. It will still taste delicious.

Also, in addition to cauliflower cooked this way, cabbage would be good as would brussels sprouts. And collard greens. Rapini. In fact, just about any of the brassicas (cabbage family of vegetables and greens) would taste good with this treatment.

Book Review: India’s Vegetarian Cooking

Reading cookbooks brings no small amount of pleasure to me; the best, however, broaden my knowledge not only of food and culinary arts, but also of culture, geography and humanity.

Monisha Bharadwaj’s Indian Vegetarian Cooking: A Regional Guide is one such book. Curling up to read it is not only a second-hand gustatory joy, it is also extremely informative in the best possible way. Filled with cultural background for every region and state of India, the book gives what is often missing from other cookbooks when they present ethnic foods: context.

Already familiar with Bharadwaj’s friendly and unassuming yet authoritative prose from her first book, The Indian Spice Kitchen, (an exceptional reference work on the ingredients used in Indian cooking) I was thrilled to see that she had applied her considerable talents to illuminating the vast array of vegetarian recipes from every corner of India.

This book does not disappoint; Bharadwaj displays the breadth and depth of her knowledge of Indian food without either overwhelming or boring the reader. Instead, she gives the perfect amount of detail to pull the imaginative reader into her narrative and the curious cook into the kitchen.

And if her delectable prose fails to entice the cook into recreating the flavorful recipes contained therein, the myriad sensual photographs will do the job. This volume is lavishly illustrated with photographs of ingredients and finished dishes of course, but also features breathtaking landscapes and portraits of the people of India. Temples, kitchens, jungles, gardens, open-air marketplaces and rice fields all come to life, capturing the vivid colors and textures of each of the states that Bharadwaj highlights.

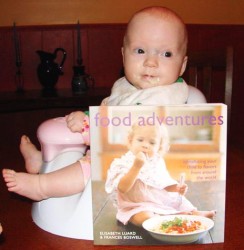

Let me put it to you this way: the photographs in this book are so lovely that Kat insisted upon looking through the book with me. Literally–she saw the book sitting on the table next to us, and leaned toward it, reaching out a hand and vocalizing intently. When I picked it up and set it in front of her, she put both hands on the cover, which features tindora gourds with garlic, mustard seeds and cumin, and murmured wordlessly to me and it. She sat with me, and patiently, and with great excitement, went through the entire book, gazing rapturously at each photograph, and showing a great deal of interest, not only in the food photographs, but also the pictures that featured people going about their daily lives or cooking. Considering that the book is 173 pages long and Kat is just now about six months old–that tells you how colorful and interesting the photographs are.

But how are the recipes?

So far, the one I have cooked has turned out very well. Grouped together by general region, starting with the north, moving to the west, then the south and the east, the recipes covered include grain dishes, breads and pastries, yogurt and milk-based dishes, bean and lentil dishes, vegetables of all sorts, and sweets. The ingredients include a few native Indian vegetables, but most of the veggies are easily found in the typical American grocery store, greengrocer or farmer’s market. Bharadwaj includes suggested substitutes and variations with some recipes, which I think most Americans appreciate, even though most of the ingredients are available at any well-stocked Indian or Asian market.

I marked about twenty dishes that I really must cook in the near future, but I expect to make more. Look for reports on them as I work through the book; I really like to share recipes from the cookbooks I review so that readers really can get a feel for how practical each book really is.

Based on my experience of the book thus far, however, I have to say that it is a valuable resource for those interested in gaining an insight into the varied traditions of vegetarian cookery that exist in India. I hope that it helps banish the idea that vegetarian food has to be bland, boring or somehow lacking; this is simply not the case. Bharadwaj shows us that vegetarian food can be as beautiful, exciting and fulfilling as a meat-based diet, and her cookbook is deeply inspiring to me.

I cannot wait for the local vegetables of spring, summer and fall to start flooding the farmer’s market now, so I can start cooking up a storm from this book!

Cookbook Review: Food Adventures

Kat is just a few days shy of her six-month birthday, and her new pediatrician, after hearing how the wee tenacious one has been dive-bombing after my toast every morning, has given us the all-clear to start her on solids. In the US, that means giving her rice cereal, which is deemed the most harmless of food substances; in China, many a baby’s first solid food is congee or jook–a porridge made of rice cooked until it falls apart.

So, with a happy heart and light hands, I mixed up a bit of fortified rice cereal with expressed milk and let Zak feed Kat her first solid meal.

While watching Kat learn to take cereal in her mouth, roll it around, taste it and swallow it, it was only natural that I think about what other people from around the world feed their babies when they are ready to start taking nutrition from solid food.

It seems that I am not the first person to think such thoughts; two food writers, a mother-in-law/daughter-in-law team, have also wondered enough about the issue of what babies and children all over the world are fed to actually write a cookbook on the subject.

Food Adventures: Introducing Your Child to Flavors from Around the World by Elizabeth Luard and Frances Boswell can be seen as a reaction to the prevalence of “kids’ food” made especially for and marketed toward children in the United States. With many children eating separate meals from their parents based upon processed foods like macaroni and cheese and chicken nuggets, the authors of Food Adventures are urging parents to avoid the entire idea of children’s food as a separate category and instead give their children a taste of the global kitchen from the beginning.

The very first chapter deals with traditional “first foods’ from various parts of the world, including a chilled Scandinavian blueberry soup, and a leek and potato puree from Belgium. Each recipe comes with a tiny bit of cultural information and recommendations for the proper age to start the child on the food. I was unhappy, however, to see junket–pudding made from whole cow’s milk–suggested for the consumption of six month old babies. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends no whole cow’s milk for children under the age of one year, because the proteins are not digestible by human infants. In addition, there is too much of some minerals, which can lead to overburdening the kidneys of babies, and of course, there is a risk of inducing a milk allergy if cow milk is given to early to a child.

That is the largest complaint I have with the book; unfortunately, it is fairly significant.

Later chapters, however, are delightfully written. The authors advocate that parents engage children’s senses at the table, teaching them to delight in food that is pleasing to the eye and nose as well as the palate. My favorite chapter is entitled, “Sniff and Seek,” and includes recipes meant to introduce children to the myriad scents that aromatic ingredients such as spices and herbs have to offer. Recipes such as Thai Chicken Rice with Lemongrass and Lime Leaves and nutmeg-scented Swedish Meatballs in Cream Sauce give parents ideas for dishes that are not only delicious but engage a child’s exploration of the olfactory aspects of food and cookery.

Playfulness is encouraged as well, with whimsical recipes like “Cinderella’s Midnight Feast:” a pasta dish that includes ricotta and pumpkin. Role-playing and make-believe, two activities at which children excel are used to help learn manners in a chapter called “The Restaurant Table.” Here the authors shine. Recipes from all over the world are presented along with a discussion of how children are brought to the table in each culture. The proper table manners for each culture are explained, with the suggestion that children playact that they are in restaurant serving these foods at the dinner table, while Mom and Dad model table manners appropriate to the country represented at dinner.

(That is fine and good, though I suspect for younger children the continually changing set of table manners might be a bit confusing. For older kids, however, I think it is a great idea.)

From a parent’s point of view, the recipes look and sound quite tasty. In addition, most of them are fairly simple, with most of the ingredients being easily accessible at well-stocked local grocery stores. The recipes all look easily doable not only by parents for kids, but -with- kids, whether they are underfoot, slung on the back or helping on a stool at the counter. Even the whimsical recipes sound edible to the adult palate; it is only the names and presentation that are playful. The dishes themselves are solid, real food meant for people who like flavors from all over the globe.

I rather enjoyed the book, and I have to admit that Kat likes it, too. From the first time she caught a glimpse of the book, she grabbed it and started cooing and jabbering to the little girl eating spaghetti on the cover. She thoroughly enjoyed leafing through the book, looking at the pictures of the foods, and the kids eating, cooking and playing with them. I look forward to trying out some of the recipes when she is older, though I will stick with her rice cereal for now. (Soon, though, soon, I will be roasting sweet potatoes and mashing them, and pureeing sweet garden peas with mint.)

Bland and typically American as rice cereal is, I have to admit–I added the tiniest pinch of ground cardamom to it before giving it to Kat. It gave the cereal the heavenly scent of kheer–Indian rice pudding–and I cannot help but think it improved the flavor of it immensely. I cannot help but think that the authors of Food Adventures would be pleased.

(Here is a big thank you to Dan Trout for the great photos he took last night of Kat’s first solid meal which are illustrating this post.)

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.