Food in the News Returns

It has been a while since I featured food in the news here, so I thought it was time to play a bit of catch-up.

Here are a few stories that have piqued my interest in the last couple of days:

Grass Fed Beef Found to Be Healthier: The Washington Post reported yesterday that a study published by the Union of Concerned Scientists has found that the chemical composition of milk and meat from grass-fed cows to be significantly different from the milk and meat from feedlot cows fed grain.

The study is the first to synthesize the information gleaned from most of the English-language research into the issue of grass-fed beef (25 individual studies were chosen for analysis)where amounts of total fats, saturated fats, omega-3 fatty acids, and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) in both pasture-raised and conventionally raised beef and dairy cattle were compared side by side. The report also combines analyses on the nutritional, environmental, and public health benefits of grass-based farming techniques.

The study found that grass fed beef and milk contained higher levels of Omega-3 fatty acids–beneficial fats that help lower the risk of heart disease, may protect the body from cancer and have been shown in a few studies to have positive benefits for suffers of bipolar disorder.

The total amount of fat in grass-fed beef is also lower than that in corn-fed beef, which also enhances its healthfulness.

One thing that the article didn’t point out, but which I, of course, thought of was that cattle that have been raised completely on grass for several generations, or on grass and then “finished” with organic corn, are not likely to have BSE, which is most likely contracted through giving cows feed rendered from other animals. Considering that a third cow with BSE has been confirmed in the US, and the worthless gits at the USDA are talking about cutting back on testing for BSE, I think that grass-fed, locally raised beef from farmers you know and trust is suddenly going to rise in popularity across the country.

Dabba Wallas Come to the US: Okay, this is utterly cool. I know some of you are saying, “Dabbawho?” so, let me explain. Dabba wallas are the name for delivery guys who carry tiffin boxes–tin containers with three layers, one for bread or rice, one for the main course, and one for pickles or a side dish–all home cooked foods–and deliver them to office buildings in India. I read about them in Lizzie Collingham’s book, Curry: A Tale of Cooks & Conquerers, and I thought to myself–wouldn’t that be cool if they had dabba wallas here?

Well, according to the New York Times, the dabba wallas are here! In major cities across the country that have sizeable South Indian populations, women have started businesses making home cooked lunches which are delivered to customer’s workplaces. In India, wives cook meals for their husbands and send them with the dabba wallas–here, entrepreneurial women have started selling their homecooked meals by subscription.

Many of these women now work in rented kitchens, have websites with their rotating menu offerings and customers can order online and pay by credit card.

And yet, all of the food is cooked carefully, in small batches, so it is still homemade, healthful and delicious.

That is just plain awesome.

Alice Waters Plans Slow Food Expo: The San Francisco Chronicle reported yesterday that Alice Waters is planning to pull the biggest artisinal food show the US has ever seen out of her sleeve for Autumn 2007 in San Francisco.

Modelled after Slow Food’s wildly popular Salones del Gusto, which is held in Torino, Italy, every two years, the show, tentatively titled, “Slow Food Nation,” will feature 200 farmers and food producers from the Bay Area, elsewhere in the US, and from other countries. There will be tastings, seminars and films promoting the ideals of delicous, carefully crafted food.

Waters hopes that this show will then move on to other areas of the US, so that the bounty of local farmers and food producers from other regions can be showcased in coming years.

That sounds like my kind of party. I guess we’ll be visiting the Bay Area again next year….

Asian Kitchen Equipment Essentials

A reader recently posted a request on my Ten Steps to Better Wok Cookery essay, asking that I do a post on what I consider the most necessary pieces of Asian kitchen equipment are, what they are used for and where to find them.

Before I jump right into the list, I want to remind my readers that this is a pretty personal list. Keep in mind that I mostly cook Chinese, Indian and Thai food, so my list is going to be weighted in favor of those cuisines. I don’t do sushi at home, so that leaves out quite a bit of specialized equipment that I just don’t have.

Also, note that there are substitutions listed for many of the items. I personally, do not think that one can easily cook Asian foods without a wok or karahi, so I don’t suggest a substitute for that, but for other items, there are varied possible tools that can fill that niche. You don’t have to run out and buy every tool all at once and replicate my kitchen, but if you want to, I am giving brand names and sources for everything I suggest.

Finally–I am not including every obscure tool I have (that means, no, I am not going to tell you about my mooncake mold,interesting as it is), because I wanted to pare the list down to the basics. There are plenty of other fun things out there, and folks want to comment on them, please, feel free, but I am trying to do the short list of the utensils and tools that I think are necessary to easily cook very good Asian foods at home.

At the top of the list comes the Wok, which should come as absolutely no surprise. A good wok or karahi is simply one of the most versatile cooking utensils in the world; it is the best vessel for stir frying available–saute pans and skillets just really don’t cut it. It is also useful for braising, deep-frying, and steaming. For most American stoves, the new flat-bottomed woks are perfect, especially when you are talking about electric stoves. The hue and cry over how having a flat bottom “ruins” the wok’s best features that come from certain authors is bunk. Don’t believe them. Chinese-American families have cooked on American stoves with woks for years, and quite happily.

The material that you want your wok to be made from is either carbon steel or thin, Chinese cast iron. Heavy US or European cast iron woks are too heavy to work well. They take a great deal of time to heat up and then, do not cool down very quickly. For certain applications this is worthy, but not many. For ease of use and cleaning, go for the carbon steel or Chinese cast iron, which is enamelled on the outside to protect the very thin iron from shattering. Do not bother with nonstick woks, Calphalon anodized aluminum woks or stainless steel woks. They do not heat evenly, they do not keep a nonstick surface, and they are not easily cleaned.

The issue over which kind of handles to get–the double-handled Cantonese style, or the long, single-handled Northern “pao” style is up to the individual cook. I have one of each; my cast iron wok is Cantonese and my carbon steel wok has a single, long handle so I can toss the ingredients with one hand.

Where does one obtain woks like this? I suggest you mail order from The Wok Shop in San Francisco. You can call and place an order or use their website. The owner, Tane Chan is always available to answer questions and she is terribly helpful. Her prices are great and her shipping prices are fair.

To go with the wok, you need three tools. One, is the Bamboo Brush for cleaning it. This sounds kind of silly–but I very much advocate the use of the traditional bamboo scrubbing brush to properly clean a wok without destroying the seasoning as it builds up over time. There are other practical reasons to use it besides that. To properly clean a cast iron or carbon steel wok, you need to stick it in the sink and start scrubbing as soon as it is off the fire. That means the wok is blisteringly hot. Which would you rather have between you and that hot metal–a little, squishy, inch-thick scrubby-sponge that will likely melt, or a nice sturdy, eight-inch long bundle of bamboo? See what I mean?

You also need a Wok Shovel, which is shaped perfectly to scoop food around the sloping sides of the wok and toss it around. You can see it up in the main illustration for this post; it is the implement that looks like a shovel, strangely enough. Get as long a handle as you can work with, especially if you have a very hot stove–it keeps your hands out of the hot zone when you are working.

The other tool in that photograph above is the Wire Skimmer. This bamboo-handled piece is great for dunking and lifting items into and out of deep frying oil in the wok. It is also good for retrieving wontons and dumplings from boiling water, or portioning out noodles from a pot. All three of these tools are quite inexpensive from The Wok Shop.

Next in the list of necessary items is one or two very sharp Chinese Cleavers or Knives.

Asian cookery requires a lot of cutting; in fact, the proper cutting of ingredients is probably the most time-consuming part of prep for many Asian cuisines. A lot of Chinese chefs and cookbook authors emphasize the use of the cleaver, but in truth, you can do nearly every kind of cutting you would need to do with either a santoku-style knife or a Western style chef’s knife. One exception to this assertion is the technique of double-cleaver mincing, where the cook uses a matching pair of cleavers, one in each hand, to mince a chicken breast, piece of pork or beef, into fine pieces by rhythymically chopping in rapidly alternating beats.

But the point is, if you already have a really sharp knife that you can cut paper-thin slivers of meat, scallion or ginger with, then you can do without a cleaver. It just isn’t necessary.

That said, I like using cleavers, and used to use them all the time, until I started using Japanese style chef’s knives, known as santoku. They combine the best parts of a Western chef’s knife and a Chinese cleaver. They have the maneuverability of a chef’s knife, and the very, very sharp edge of a cleaver. I think that they are a great all purpose knife, and they have become the ones that I tend to use on an every day basis. Global makes a good santoku, but my very favorite knives of all time are Shun by Kershaw. I have two of them, the Shun Classic santoku and the Elite chef’s knife, and they are not only gorgeous to look at, but a dream to use; they are the sharpest knives I have ever owned and they make it simple to cut grassblade-fine slivers of ginger or paper-thin slices of meat.

In choosing a knife it is important to get a feel for it before you buy it. That is why I suggest that you go to Sur la Table or Williams Sonoma, or any good independant kitchenware, hardware or cutlery shop that carries a large selection of kitchen knives. You want to be able to feel what these knives are like in your hand. You want to pay attention to the balance of the knife, the weight of it and the feel of the handle in your palm. Knives come in all shapes and sizes, and you need to find the ones that feel right in your hand. On your first shopping trip, you don’t even have to buy the knives you pick out–if you can get better prices online, then thank the salespers and tell him that you are thinking about it and then order the knife you chose from someplace cheaper, especially if you are on a tight budget.

Whatever knife or cleaver you choose, make certain to get a very sharp one and take pains to keep it that way. Learn how to sharpen them so that you can maintain the edge properly and you will get decades of use out of your fine cutlery. Get a sharpening stone and a steel, and have someone show you how to use them, and at the first sign of dullness, sharpen your blades back up. A dull knife is a dangerous one.

Once you have a knife, you need a good Cutting Board. Use bamboo, wood, or soft, heavy plastic for your cutting boards, never glass, masonite or thin, hard plastic. This is to protect the edge of your now very sharp knives. Hard surfaces will dull a knife quite quickly, so to protect your knives, invest in a good, easy to clean, board with a knife-friendly surface. Chinese chefs like these heavy, thick, round chopping blocks that traditionally are made from the cross-section of a tree trunk. I generally use my bamboo cutting board or one of the heavy plastic ones–my favorite plastic ones have gripper feet on one side, which helps keep them still and steady on the countertop, but it also means that you can only use one side of the board.

A Rice Cooker is not a necessity, but it sure is nice, and if you eat a lot of rice, like my family does, it will pay for itself in convenience and ease of use within a couple of weeks. I used to make rice on the stovetop all the time, but when we moved into the last house we owned, the cast iron electric burners on the stove confounded me. I burned the rice every time, no matter what technique I used. It got so irritating, I gave up on my ability to cook rice on the stove, and bought a rice cooker, and I have not looked back.

This from the woman who made fun of her Singaporan friend in culinary school because a chef told him to make steamed rice and he came to me and whispered to me, “How do I make rice on the stove?” I laughed at him and was incredulous until he said, “Everyone in Singapore has a rice cooker. I know how to use those–I have no clue how to cook rice on a stove.”

I ended up teaching himhow to steam rice on the stove, but I also learned something valuable from him . A rice cooker is a piece of equipment that you plug in, pour the rice and cooking liquid in, close it, turn it on and then walk away. It does all the work. And if you get one of the “fuzzy logic” cookers that has a sensor in it that can tell the machine how much water and rice you put in–if you screw up the amounts–the cooker will adjust the cooking time and temperature and still give you perfect rice. Mine is a Zojirushi, and has worked faithful, almost daily (At least four times a week) for four years, and shows no sign of quitting.

Using a rice cooker frees up a burner on the stove, and frees the cook up to concentrate on the timing of other foods, without having to worry about the rice. I would never have thought I would have loved one as much as I do, but now, I would never be without on. I highly recommend them. You can usually find a respectable collection of rice cookers of all sizes and styles at your local Asian market, or you can order one online from eKitron.

If you are going to cook a lot of Indian or Thai foods, you will need a Grinder of some sort. Whether you go in for a mortar and pestle made of stone, or the Sumeet Multi-Grind, or an electric coffee mill and a food processor or blender, you will want something to help you grind dry and wet spices into curry pastes. I have used all of the above methods, and while I still have my mortar and pestle, and will probably get a really large one at some point, I am very fond of and use my Sumeet Multi-Grind all the time. It is a really fine piece of equipment that will grind up any wet or dry ingredient that you would have into a very smooth paste (or powder if all the ingredients are dry), including rock hard galangal and chunks of cinnamon stick, without fail. The parts of the machine that come into contact with the food are all dishwasher safe, so they are simple to clean.

I have had it for nearly eight years and have used it at least four times a week, and it has never choked, failed me or even considered not running. You can order it directly from the manufacturer, or pay more and order it from Williams-Sonoma. I recommend ordering from the maker–that is how Zak got me mine, after all.

If you decide to go the route of the mortar and pestle: stone ones are available in most sizeable Asian markets that cater to Thai and Indian people. They are very tough, very durable and beautiful, and are large enough to make a lot of curry paste at a time, without having to resort to the batch method of curry paste making.

Remember, that if you use a coffee grinder for a spice grinder, that it can only handle dry ingredients. To puree wet ingredients into a paste, you need to use a coffee grinder in conjunction with a blender or food processor, which necessitates using two tools instead of one.

The final necessity of the Asian kitchen is a set or two of Bamboo Steamers. These beautiful baskets are perfect for making steamed buns or dumplings, but you can also steam anything in them, including fish. Just put the fish or whatever meat item you want to steam on a heat-proof plate that fits inside the steamer basket, cover the basket and put it over boiling water. It is as simple as that. These baskets are made to stack on top of each other in a tower, so that you could steam an entire meal in them if you wanted. I have even used mine to make tamales.

Bamboo is superior to metal for making steamers because the water that condenses from the steam is absorbed by the bamboo lid; it doesn’t drip back down on the food, diluting the flavor of the seasoning. They are also inexpensive, durable, and look beautiful as serving pieces on the table as well. You can purchase them cheaply at any Asian market that carries kitchenwares, at places like World Market and at The Wok Shop.

These are the “essentials” of the Asian kitchen, in my opinion. It is possible I left something out, but I tried to pare the list down to those things that I thought would make a beginning cook’s life easier as they took up the challenge of learning Asian cooking at home.

Pollo ala Plancha

Ever since I did the Baker’s Dozen Cookbooks post, I have been craving Cuban food. Since there is a distinct dearth of Cuban restaurants in Athens, Ohio, it fell to me to get in that kitchen and make myself some beans, rice, plantains and other soul-stirring comfort foods.

That big box of Meyer lemons determined what main course I would make: Pollo ala Plancha. I know that it roughly translates as “Grilled Chicken,” but the version of Pollo ala Plancha that Zak loves isn’t grilled at all. It is the dish he always eats at this tiny Cuban restaurant in Coral Gables when we visit his parents; I cannot remember the name of the place, but thier food is just perfect. Very simple, very well-presented and very, very flavorful without being overwhelming.

Their Pollo ala Plancha is sauteed in olive oil with some garlic, and is coated in a pan sauce of sherry, reduced chicken broth, and lemon juice, with salt and pepper. It is a completely simple and utterly fantastic-tasting preparation and is one that I had not tried to replicate for him until now–mostly because I was always more interested in cooking Vaca Frita or Ropa Vieja.

Meyer lemons, however, with thier flowery-intense aroma and good balance between sweet and tart flavors would really enhance such a simple chicken dish, adding a flicker of poetry to a very homey meal.

I have to admit to cheating on the beans and rice: I made jasmine rice in the rice cooker with chicken broth, adobo seasoning and some butter, and then doctored up a couple cans of black beans by pureeing half of one can, and then adding shallots, garlic, sweet red bell pepper, thyme, rosemary, smoked Spanish paprika and adobo seasoning all sauteed in olive oil until it was soft and fragrant. I had some sofrito I had made and frozen, so I popped a couple of tablespoons of that in the pot, and stirred, and let the whole mixture simmer with some chicken broth until it cooked down to a nice, thick,dark beany goodness. Then the two were mixed together into a really good mess of comforting goodness.

And the plantain? Well, I got the ripest one that was at Krogers by digging through the bin to the very bottom where I found one that was almost black, bruised and disreputable-looking enough to be nearly ripe. It wasn’t completely mushy and sweet yet, but was still firm and half sweet, half starchy, so it fried perfectly well in peanut oil and made an acceptable side dish. Though, I have to admit that I prefer them perfectly ripe–meaning, the skins must be completely black. These fry up sweet and meltingly gooey in the middle, with a lovely crisp brown outer crust.

But when in Southeastern Ohio, one takes what gets. And unless you plan ahead for a week or so to make plantains, one has to make do with ones that are not as ripe as one would like.

Back to the chicken: while it is simple, there are a few tips that are useful. First, pound the chicken into uniformly thin pieces–about 1/4 to 3/8 of an inch thick. Do this gently, with a piece of plastic wrap over the chicken, so that the flesh doesn’t tear. I like to bring the chicken to room temperature; while this is going on, I season it well with adobo seasoning and black pepper. Once it is warm, then I dredge it in salted flour, and cook it in olive oil, two pieces per pan. When each piece is nearly done, I remove it, put it on a plate and stick it in a warm oven. When all of the chicken is done in this fashion, I put all of it on the plate in the oven, and then drain most of the olive oil out of the pan, while making sure to leave behind the browned bits of chicken and flour that have stuck to the bottom of the pan.

I like the flavor of the sauce made with butter rather than olive oil–I think it ends up being more flavorful in the long run, when I do it this way.

Without further ado, here is the recipe:

Pollo ala Plancha

Ingredients:

4 chicken breast halves, trimmed and pounded to 1/4-3/8 inch thick

1 teaspoon adobo seasoning

freshly ground black pepper to taste

1/4 cup flour seasoned with a teaspoon salt

olive oil to cover the bottom of your saute pan

1 tablespoon butter

zest of one large (about the size of goose egg) Meyer lemon, minced (you can reserve about a tablespoon of the zest in long strips for garnish if you like)

1 clove garlic, minced

1 tablespoon flour

1/4 cup golden dry sherry

1/2 cup chicken broth

juice of the same large Meyer lemon

salt and pepper to taste

Method:

Season chicken breasts liberally with adobo seasoning and pepper, and allow to come to room temperature.

Heat olive oil in saute pan until it is quite hot.

Dredge two pieces of chicken in salted flour, shake off excess, and saute in pan. Allow to brown well on first side, then turn to the second. When chicken is very nearly done (it doesn’t quite spring back in the center when poked with a finger or a set of tongs), remove them from the pan, put them on a plate and keep them warm in an oven.

Repeat with next two chicken pieces.

When chicken is done and set aside, drain out olive oil, leaving behind the browned bits stuck to the bottom of the pan. Put the pan back on the heat, add the butter, and when it is hot, but not browned, add garlic and minced lemon zest. Saute until the lemon starts turning golden, stirring, and scraping up the browned bits into the butter.

Add the flour and stirring constantly, cook into a roux–this will take about two to three minutes.

Add sherry all at once, and stir until a thick smooth paste results. The alcohol will cook off, leaving behind the essence of sherry thickened to a paste by the roux.

Add chicken broth, stirring (I used a wooden spoon, but others may prefer to use a whisk for this operation) until a fairly thick, smooth sauce is formed. Squeeze the juice of half the lemon into the pan, and stir until a thick, bubbling sauce is formed.

Add the chicken back to the pan, and allow it to cook in the sauce for a couple of minutes. Add the juice from the other half of the lemon and stir.

Garnish with the reserved lemon zest strips if you like.

Serve immediately on warmed plates with black beans and rice and fried plantains.

Meyer Lemon and Ginger Pie

One of the best things about having a food blog is the people you meet.

People like the nice lady in California who read the post I wrote about Meyer lemons last year, and commented that if I wanted to pay for the shipping, she would pack me up a box of her Meyers from the tree in her yard and send them out to me.

So, we emailed back and forth, and she packed me up a box of Meyers with some pink grapefruit thrown in for fun, and I arranged a UPS pickup and had it shipped to me.

And about a week later, I had a box of beautiful, huge, ripe, fragrant, delicious Meyer lemons on my doorstep. (I paid for ground shipping–the two day shipping price from there to here was beastly expensive.) Only one lemon did not survive the journey–the rest were in great shape.

What did this kind lady ask of me in return for her sweet offer to share the fruit from her tree?

That I post a few new recipes for Meyer lemons.

So, here we are. I have a box of lemons (one of which I sliced up and just plain old ate out of hand), and I need to figure up some new things to do with them.

The first thing that struck me was this is the perfect time to make a recipe I have been meaning to make for nigh on twenty-five years.

I read about this 19th century recipe that originated with the Shakers, a sect of ecastatic Protestant Christians who lived in communes and had visitations from angels, and I wanted to make it right away. My boyfriend’s sister thought it sounded amazing, too, but somehow, the two of us never got around to making it–in large part because we were not so good at making pie crust. But you see, now that I spent a summer perfecting pies and pie crusts, I have no excuse.

What is Shaker Lemon Pie? Well, it is simple. You slice two lemons paper thin, rind and all, take out the seeds and macerate it overnight with two cups of sugar. You stir it now and again so that the sugar all dissolves into a fragrant syrup. The next day, you prepare a crust for a 9-inch two crust pie and then beat four eggs really well, them mix them with the syrup and the lemon slices, and pour that into your bottom crust, cover it with a top crust, and bake it.

And that is it.

Well, that is it if you are a Shaker, which I am not, which Zak is very glad of, for the Shakers were celibate, which explains why they kind of died out.

But, if you are like me, and like the flavors of lemon and ginger together, you have to gild the lily a bit.

So, I added a tablespoon of Stone’s Original Ginger wine to the syrup, along with two tablespoons of crystallized ginger that I had minced up.

The ginger mixed with the floral-scented Meyer lemons took the pie into orbit. It was just plain old amazing.

So, here is the recipe, if you couldn’t get it from my description.

Meyer Lemon and Ginger Pie

Ingredients:

2 large Meyer lemons sliced paper thin (If you only have small lemons, use about 6-8 of them.)

2 cups brown sugar

1 tablespoon Stone’s Original Ginger (optional–you can substitute ginger juice from fresh ginger)

2 tablespoons minced crystallized ginger

pastry dough for 2 crust 9-inch pie (Note: I made this crust with all butter–Plugra to be exact)

4 large eggs, well beaten

Method:

The night before you want to bake your pie, slice your lemons very thinly with a sharp knife, discard seeds, and put into a glass bowl, with as much juice as you can collect from cutting board. Add brown sugar, Stone’s, and ginger, and stir until well combined. Cover tightly with plastic wrap and put in the refrigerator to macerate overnight. Stir it once or twice to make sure the sugar all dissolves into a fragrant brown syrup.

The next day, preheat oven to 450 degrees.

Prepare pie dough and roll out. Line 9-inch pie plate with dough, and trim edge neatly.

Take the well beaten eggs and stir them into the lemons and syrup. Pour into prepared pie shell, cover with the other piece of rolled out dough, trim edges, flute and seal edges, and cut vents in the center.

Cover edges of pie with foil or an edge guard, also known as a “Pie Chakram” if you are a weirdo like me, and bake at 450 for fifteen minutes. Turn the heat down to 350 degrees and bake for twenty minutes more.

Allow to cool completely on a rack before cutting.

Note: Of course, I am trying to figure out what other citrus I can do this with. I am thinking a mixture of Meyer lemon and blood orange, like the pomegranate-colored Moro. Zak is all up in that, so I may have to go grab some blood oranges before the season is through so I can give it a shot and see what happens.

But the flavor is wonderful, particularly considering how few ingredients the pie filling has–it is tangy, sweet, floral and lemony all at once, with just a hint of ginger heat.

A Baker’s Dozen of My Favorite Cookbooks

Meg, one of the chefs at Too Many Chefs, asked me a couple of posts back to suggest a few cookbooks to her, as she felt that she needed more.

As one who lives in a house littered with thousands of books, hundreds of them cookbooks, I am happy to oblige her request, though I must point out that my list of favorite cookbooks is eclectic in the extreme, and features very few books that are from traditions related to either regional European or American cuisine. And there is not a general cookbook among the lot.

Make of that what you will.

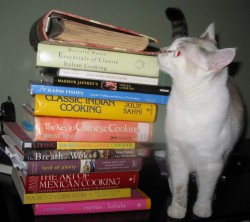

These titles are in no particular order, other than the order in which they were taken from their cosy shelves in the kitchen carried forth into my office and dumped unceremoniously upon my desk. Where, as you can see, they became objects of immediate interest to the resident felines.

Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking by Marcella Hazan: This book comprises both The Classic Italian Cookbook and More Classic Italian Cooking in one volume. This is one of the few, the proud, the European cookbooks in my collection that can boast food stains on more than one or two pages. When I want to make Italian food that tastes Italian and not Italian-American, or American-Italian, this is the book I reach for. Marcella writes like she is standing next to you in the kitchen, with a wooden spoon at the ready: she’s bossy. I like that about a cookbook writer. She tells you what to do, how to do it, when to do it, why to do it AND she does it all in such an authoritative voice that you cannot help but obey. And, in obeying, you end up with really tasty food. Marcella is one cook I love, honor and obey, at least, most of the time. I will admit to going against a few of her rules over the course of the years, and these days, I can mostly get away with it. I know which rules to bend, you see. But for a good lesson in real Italian cookery, you cannot beat following Marcella’s orders–she will pull you through every time.

It Rains Fishes: Legends, Traditions and the Joys of Thai Cooking by Kasma Loha Unchit: This book, which is sadly out of print, has been read more times than I can remember. You see, I like cookbooks that you can read, in addition to cook from. In fact, I would say that I read cookbooks more than I actually follow the recipes from them–especially if you only count “following” recipes as meaning “following them to the letter.” Because, I seldom follow any recipe to the letter, but that is another story. We are talking about It Rains Fishes here. Kasma is a heck of a storyteller, in addition to being a damned fine cooking teacher. Her words combine with really delightful water color illustrations by Margaret DeJong and a great collection of Thai recipes to make a cookbook that entertains, educates and entices the reader all at once. If I lived in the Bay Area, I would take Kasma’s Thai cooking classes; since I do not, I have used her recipes to teach myself how to cook excellent Thai food, starting with fresh curry pastes and ending with finished dishes full of fragrance and flavor. This is definately a book to seek out.

Madhur Jaffrey’s Quick & Easy Indian Cooking: Do I need to mention this is by Madhur Jaffrey if her name is in the title? Okay, I won’t then, but I have to admit that I have used probably more recipes from this book than from any other cookbook, without a shadow of a doubt.It is probably the most stained cookbook in my collection that got its stains from my kitchen; I have some antique ones that are more disreputable looking than this one, but the slopping wasn’t done my my own hand, so it doesn’t count. I have already said that Madhur is a Devi of the kitchen, and I reiterate it here–she is divine. Her recipes have never failed to work, to taste wonderful, to satisfy myself, my family, my guests, and my clients–many of whom were Pakistani. Her recipes are just plain old good, simple and they work as written, though, they are always amenable to the cook’s own flourishes and ornaments. This is also the cookbook that pushed me towards getting my first pressure cooker, and caused me to utterly fall in love with that method of cooking.It is wonderful. You get an amazing depth of flavor in a very short period of time, with a minimum of effort. In today’s hurried world, this book, and a pressure cooker are the answer for rushed families who want to cook and eat Indian food and have no clue how to start.

Classic Indian Cooking by Julie Sahni: This is probably my second best all-time favorite Indian cookbook that shows its status as a “best beloved” volume by the number of ingredient stains on its pages.Julie has taught Indian cookery out of her home and through other venues in New York City for decades, and her careful prose and explanation shows this. She is one of those writers whose clear explanations tell the reader what a patient teacher she is; it is obvious that she has led many Westerners through the mysteries of Indian cuisine many times. She knows the path very well, and is ready for every twist, turn and question that can come up. She also writes with a very infectious enthusiasm that is very hard to ignore; I cannot imagine anyone reading it and not wanting to jump right up, run to the kitchen and whip up a batch of Shajahani biryani, even if that means they have to make a batch of lamb korma first. My favorite chapter is the one on breads; Julie is the first author who made me brave enough to attempt parathas.

Tandoor: The Great Indian Barbeque by Ranjit Rai: Okay, if you look at the authors of all the other books, you will notice that most of them are women. I am not sure why that is, exactly, except that I tend to prefer books that are not written by chefs, most of whom are men. Why? Well, even when I was in culinary school, I tended to prefer chefs who made real food, not art food, and a lot of chef’s cookbooks are all about art food that no home cook is really going to be able to recreate, so who wants to read that? I mean, I have plenty of books by male authors, but not one them are as well loved as the ones by these talented women. Except this one. Ranjit, a successful businessman and philanthropist, made it his life work to document the history, lore and recipes surrounding the wood-fired clay tandoor ovens of India. And his book, which is filled with luscious photographs, delicious recipes for tandoor dishes one never sees on menus here in the US, and the tale of the tandoor, really jumpstarts my creativity. He writes with clear wit, and his recipes are simple and easy to follow. Look for some tests of his dishes this summer when it is time to fire up the grill again.

A Taste of Persia by Najmieh K. Batmanglij: This little volume has become a favorite not only because I am very fond of the flavors of modern Persian (Iranian) food, but because it has helped establish a hypothesis in my mind. My hypothesis is that Persian cuisine is probably one of the most unsung, yet quietly influential cuisines in history, even if most Americans wouldn’t know a Persian dish if one bonked them upside the head. (Don’t worry–I will write about this one day–I keep meaning to and keep forgetting.) Najmieh is another great teacher and writer who tells stories about every one of the recipes she presents in the book. She quite successfully places Persian food in the context of culture and history, which I appreciate a great deal, because I am a firm believer that food is one of the main modes by which culture is transmitted from one generation to the next. My favorite recipes in the cookbook are the ones for eggplant and for pillau, the bestest of which is the cherry pillau recipe I blogged about last summer.

Memories of a Cuban Kitchen by Mary Urrutia Randleman and Joan Schwartz: I love me some Cuban food. Zak’s parents live in Miami, Florida, and whenever we visit them, we go eat Cuban food at least three or four times. Neuvo Cuban at the tony upscale restaurants is great, but we are more likely to jump into the traditional stuff at little Mom and Pop neighborhood places where very few people speak English, because the homestyle food is where it is at. Black beans and rice, soft, ripe plantains fried crispy on the outside and melty-sweet on the inside, platters of vaca frita (fried cow–beef that is braised until tender then crisp fried) with fresh sweet onion and sour lime, and lemony-sauteed chicken–my mouth is watering just thinking about it. With the help of this cookbook and the new availability of plaintains up north that are just ripe enough to sit on the counter to finish ripening before they mold (when they are stark green, often they would go bad before ripening all the way), I have been able to reproduce our favorite Cuban foods even up here in Ohio. On top of everything, Mary wrote a cookbook full of personal stories of life on her grandparents’ cattle ranch in Cuba, which makes for utterly fascinating reading. If you like Cuban food, this is a must-get book. If you don’t think you like Cuban food, read this book, try a recipe and then realize that you do indeed like Cuban food. (I cannot imagine anyone not liking Cuban food that has tastebuds and a pulse, really.)

The Art of Mexican Cooking by Diana Kennedy: Once again, here is a writer who is so thorough, so enthusiastic, so knowlegeable, that a reader cannot help but learn from her. Diana is an Englishwoman who has lived in Mexico for decades, where she dedicated herself to learning as much as she could about the regional cuisines of that often derided country and then presenting what she learned in a series of exhaustively-written cookbooks. It is hard to pick just one as a favorite, but I think this is it. The only thing that keeps it from perfection is the underutilization of illustration; when learning technique-heavy cuisines, I have found that good illustration, whether in line drawings or clear photographs, are invaluable to the student. They can take the place of paragraphs of explanation, though, truly, I wouldn’t want to excise a single word of Diana’s lucid, exacting prose. It would be a shame.

Land of Plenty: Authentic Sichuan Recipes by Fuchsia Dunlop: I have sung Fuchsia’s praises in this blog before, and I probably will again, especially when her book on Hunan cuisine comes out–whenever that will be. This is the single most important book on Sichuanese food published in the English language. Period. End. Of. Story. Fuchsia speaks the language, and while she was in Sichuan province, she attended the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine in Chengdu. You can’t get anymore authoritative than that and be a Westerner, unless you were born in China, and grew up there. Not only does Fuchsia know her stuff, but she is really good at telling stories, which by now, one should know is an important qualification for a cookbook writer in my universe. But Fuchsia isn’t just engaging and witty, and has the cooking chops, but she is able to describe in detail the cooking techniques, ingredients and flavor combinations that make Sichuanese food completely unique. Unlike the way it is often presented in US restaurants, as “Cantonese” food with a slop of chile garlic paste, the cuisine of Sichuan is very different from other Chinese regional cuisines and Fuchsia is the first author to really bring this point across in a way that is accessible to the average Westerner. I also appreciate that she doesn’t shy from including recipes that might never be cooked by the average American or British cook, such as “fire-exploded kidney flowers.” I have featured two of her recipes here:Rabbit with Sichuan Pepper and Red-Cooked Beef with Turnips.

The Key to Chinese Cooking by Irene Kuo: Another out-of-print classic (though it is easy to find for a good price at Amazon, Bookfinder or ebay), Irene’s weighty tome is a worthy introduction to the techniques, ingredients and flavors of good Chinese cooking. Again, there are very few illustrations, which is a problem when students are learning a technique-heavy unfamiliar cuisine, but the explanations are so clear and concise that the lack is minor. Important techniques such as holding a cleaver and the many cuts it is used for are adequately illustrated with very good line drawings, so the quibble is a minor one. A member of an old aristocratic family in China, Kuo’s marriage to a general and a diplomat brought her and her culinary knowledge to the United States and Europe, where she hosted many banquets showcasing Chinese cuisines. Later, she opened two very successful restaurants in New York City, and she taught Chinese cookery extensively there and in other places around the country. It is obvious that she had taught Westerners Chinese cuisine for years before she wrote her book, because, like Julie Sahni’s ability to anticipate questions and answer them before they arise, she is very thorough in her explanation of the mechanics of every technique she introduces. Working from this book is like having a Chinese auntie at your elbow, guiding you along as you learn to cut vegetables, cook rice and stir fry.

Yan-Kit’s Classic Chinese Cookbook by Yan-Kit So: This is one of those cookbooks you give to someone who learns visually. It is just loaded with photoraphs, from the first page, to the last, all of them clear with natural coloring and food styling that doesn’t look overly styled. Every finished dish is pictured, garnished and made beautiful by loving hands, and the first forty-five pages of the book are taken up with step-by-step photoessays illustrating the all-important techniques of Chinese cookery, from cleaver work to stir-frying in a wok. Ingredients that may be unfamiliar to the novice are photographed and described, and on every page, the text is just as illustrative as the pictures. I assume that the lady in all the photographs is the author (who just recently passed away, alas), who demonstrates every technique with ease and grace; while her writing is generally devoid of stories, her description of the hows and whys of Chinese food more than make up for the lack. Besides, her personality comes through in the photographs, if, indeed the lady in the pictures is the author. All of that aside, the recipes I have used from this book, (one of which I just presented here: Beef with Mangoes), have all worked quite well for me and for Morganna. This is one of the books I gave her for Yule before she came to live with me when she wanted to learn to cook Chinese food. She started working through it alone and did quite well, cooking several dinners for herself and relatives with just the book and a few phone calls to me to guide her.

The Breath of a Wok by Grace Young with photographs by Alan Richardson: This has got to be one of my favorite cookbooks ever. For one thing, it is not just a collection of recipes, but is a work of food anthropology and history, with striking photography documenting the history, development and culture of the wok in Chinese cookery. It is a remarkable work, spanning thousands of years and miles, with beautiful recipes gathered from home cooks and chefs from China and all around the world. Grace is a consummate storyteller, and she is just as adept at writing recipes as she is at writing history. She is a dear, funny lady, who has deft hands with a wok, too–I was priviledged to meet her and assist her in teaching a class last year in Columbus, Ohio where she prepared a Chinese New Year menu built from recipes from this book. She was a very good teacher, and went out of her way to teach the symbolism and history of each dish along with the ingredients and technique. It was very obvious to me that she she felt that culture and cuisine went hand-in-hand. For a taste of one of her dishes from this book, try her Stir Fried Lettuce with Garlic; I know it sounds odd, but I had it that night in Columbus, and it is utterly divine. The one difference between this recipe and the way she cooked it then was instead of iceburg lettuce, she used romaine, which was amazing.

Jerk: Barbeque From Jamaica by Helen Willinsky: I have never been to Jamaica, but I know that I will be eating if I ever make it there. Jerk. Jerk pork, jerk chicken, jerk beef, fish–I don’t care what critter is is, put that jerk rub on it and grill it over a smoky fire and I am so there. Jerk is fine stuff, make no mistake, fiery with chiles, bright with allspice, tingling with ginger and bursting with garlic, thyme, peppercorns and other good stuff. It is just plain old good eatin’. I think that this cookbook has to be the most disreputable looking one in my collection, now that I get a good look at it. It also smells–like jerk of course, as it has had jerk-rub sticky fingers perusing it more times than I can count. It is out of print, but you can get plenty of copies used at Amazon for a good price. But what you want to know is how are the recipes? Well, the fact is–they are great. I have made a bunch of them, and in fact, jerk is a summer standby around here, much to the great joy of all. The recipes are all fantastic. Just great. I have made the barbequed meats, the beans and rice (with coconut milk–yum!), meat patties, which are like Cornish pasties that taste good because they are all spicy and tasty with flaky turmeric-colored pastry, and the jerk meatloaf, which is the -only- way Zak will eat meatloaf and like it. As is the case with most of my favorite cookbooks, I have gone off and riffed a few of the recipes, taking them places that Helen maybe didnt forsee or intend. Like the Asian-Jamaican fusion jerked pork tenderloin with teriyaki sauce and sesame oil in addition to the standard jerk rub that I served with a salsa of mango, papaya, pineapple and pickled ginger. Yeah, that was tasty. I should make it again and blog about it, now that I think on it….

There we are. Thirteen of my favorite cookbooks, in no particular order, with hopefully helpful, and entertaining commentary, and illustrations that include my constant companions and erstwhile assistants, the lovely and talented Lennier and Tatterdemalion.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.