Heirloom Tomatoes Are Here!

Heirloom tomatoes are a hot topic in the food world these days, with writers generally trumpeting their virtues, though some folks, such as Derek from An Obsession With Food, have conducted taste tests of some varieties of heirloom tomato and have been both underwhelmed and blown away.

What makes a tomato an heirloom? Well, they have to be from a variety that has been grown for at least fifty years, and it is most often preferred that they be open-pollinated. What does that mean? Well, that means that most heirlooms are not going to be hybrids–they are going to produce seeds that breed true. If you save seeds from open-pollinated tomatoes, you will grow a plant and harvest fruits that (barring natural mutation) have the same characteristics of the plant and fruit from which you harvested the seeds.

Most modern garden vegetables are hybrid varieties, which means they are a cross-breed between two to four different varieties of the same plant. That means that if you were to save seeds from a hybrid tomato, for example, and then plant them the next year, you would not end up with plants or fruits that were like the ones you had the year before. You would get a plant with characteristics from one of the parent varieties that were cross-pollinated in order to produce the hybrid plant.

Taste tests of heirloom tomatoes seem to be popular these days; Kendall Jackson winery holds a Tomato Festival every year that includes a tasting that is similar to the more familiar wine-tasting. At the winery tasting, tips on pairing wines with heirloom tomatoes are given, which interestingly, include matching the color of the wine to the tomatoes.

One thing I should like to point out though, is that heirloom tomatoes, like all great tomatoes, are best grown locally and vine-ripened. Much of their flavor depends not only on the variety of tomato, but also on how the tomato plant was grown, how much rain or irrigation was given during different growth periods (dry farmed tomatoes–those given very little to no irrigration give -very- intensely flavored fruits, due to the minimal amount of water there is to dilute the flavor), and what type of soil it was grown in. I have seen heirloom tomatoes shipped to my local grocery store from Florida, and I would -never- buy one of them. Sure, they have the characteristic interesting shapes and colors, but I can tell by smelling them that they are just as flavorless as their perfectly round, red, baseball-textured Floridian cousins which are picked green and ripened on the truck with ethylene gas.

In order to get a great heirloom tomato, you need to either grow it yourself, or buy it directly from a local grower. They need to be picked at peak ripeness, when they are fragile and unshippable, and they just about need to be eaten right away. Never refrigerate them–or any other good tomato, for that matter–because it takes away the flavor of the fruit. I always keep them at room temperature on my counter, and they keep for several days that way. This way, they are always at the peak of flavor and texture.

I know a lot of people go on about how ugly heirloom tomatoes are, but I disagree. Perhaps it is because I didn’t grow up eating those perfectly spherical red, crispy, flavorless fruits, and instead ate homegrown beefsteaks which were always large, fluted and somewhat oddly shaped that I am not bothered by the shapes and colors of heirlooms. In fact, the genetic diversity that heirloom tomatoes represent with their rainbow colors and myriad shapes fascinates me, and I found myself first drawn to them years ago in Maryland, because they were beautiful to me.

They looked like something out of a Dutch master’s still life; the deep violet-rubine of “Cherokee Purple” and the green-shouldered brown-russet burgundy shade of “Black Krim” attracted me right away, while the yellow and green striped “Green Zebras” tickled my sense of whimsy. Yellow and red flamed “German Striped” thrilled my eyes, while pink Brandywine looked anemic, but smelled so good I had to try it. I remember making a beeline for them at the Columbia, Maryland farmer’s market and buying up ten pounds of them, they all smelled so amazing, and looked so good.

I took them home and did my own tasting and was amazed as the variable flavors. Brandywine was very tomatoey, even if it did look watermelon-pink, while Blak Krim was spicy and acidic. Green Zebra had a kicky acidic flavor, while German Striped was sweet as a tomato preserve, without having any sugar added to it. Cherokee Purple turned out to be a favorite, with its very careful balance between sugar and acid, with a slightly musky quality that was irresistable.

That was the year I invented my Calico Salsa, which turned out to be the first way that Zak would willingly eat fresh tomatoes.

Every year since then, I eagerly await the first heirlooms of the season, and each year, in addition to just eating them sliced on sandwiches, in salads and just as themselves, I add new recipes to let them shine.

Yesterday, after picking up the tomatoes pictured above: Black Krim, Green Zebras, both Pink and Red Brandywines, and an unphotographed (but present in the pico de gallo in the yellow bowl) German Striped, I resolved to make a salsa similar to the Calico Salsa, but simpler. Instead of roasting some of the ingredients, then, I left them all raw and made what I am now calling Macaw Pico. Pico de Gallo is a raw Mexican salsa that is named for the beak of a rooster–this one, because of all of the colors of the vegetbles and fruits contained therein, I named after an even more colorfully plumed bird–the macaw.

This has a less complex flavor than the Calico Salsa, but it is just as good. It is also a second entry into this month’s “The Spice is Right,” the theme of which is “Fresh and Local.” This recipe is almost completely local–the only non-local ingredients are the two limes and the salt. All of the rest: the chiles, the cilantro, the tomatoes the sweet peppers, the onions and garlic, were either purchased at the Athens Farmers’ Market or grown on my deck.

Someday I might be cool enough to grow a lime tree indoors that bears fruit in Ohio, but until then, I will stick with the ones from Florida.

Unlike their tomatoes, which are god-awful, their limes are awesome, and make a perfect counterpoint to the rich, sweet and tart flavors of my beloved heirloom tomatoes.

Macaw Pico

Ingredients:

5-8 pounds mixed heirloom tomatoes of different colors and flavors

1 small purple onion, peeled and diced finely

3 large cloves garlic, peeled and minced

1 small red sweet cornu del toro pepper, seeded and diced finely

1/2 small purple sweet bell pepper, seeded and diced finely

2 hot fresh green jalapeno chiles, washed and diced finely

2-3 Thai bird chiles or equivalents, minced (optional)

juice and zest of two limes (grate the zest finely or mince)

1 cup packed cilantro leaves, roughly chopped

salt to taste

Method:

Peel those tomatos which do not rely upon the skin of the tomato for beauty. For example, I peeled the “German Striped,” the flesh if which is yellow flamed with red throughout the fruit, while I left the peel of the green and yellow striped “Green Zebra” intact, because the interior color is solid kiwi green. I also peeled the Brandywines, which are solid throughout, but I left the peel on the “Black Krim” because it is so pretty with the burgundy shading into deep forest green. The flesh colors are similar, but not as vivid.

Core all the tomatoes, and then dice them all into medium dice. Scrape into a mixing bowl, including as much juice as possible.

Mix in all other ingredients, then salt to taste. I like to keep the salsa on the countertop at room temperature for a hour or two to let the flavors meld slightly; then I put it all up into a quart jar or container and put it in the fridge.

It can last over a week in the fridge, if no one eats it all before then. It is great on chips, quesadillas, over scrambled eggs, mixed into chili, or used as a topping for a buritto or a taco.

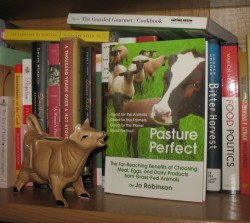

The Locavore’s Bookshelf: Pasture Perfect

Jo Robinson is the driving force behind the website www.eatwild.com, a clearinghouse for information on the health benefits of pasture-based farming which includes a comprehensive, state-by-state directory of sources for pasture-raised meats, eggs and dairy products.

For those who are not net saavy, she also happened to write this concise book, Pasture Perfect: The Far-Reaching Benefits of Choosing Meat, Eggs, and Dairy Products from Grass-Fed Animals. While she isn’t able to provide the list of consumer sources for the food products she touts in the book, and refers readers to the EatWild website, she does include the basic factual information that a consumer would need to investigate exactly why grass-fed animal products are healthier for themselves and their families to eat than the foods produced in factory farm concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs).

A fine writer and researcher, Robinson first came across information that led her to understand that the meat, eggs and milk from animals raised on grass was fundamentally different from those raised on grain (and less savory foods such as manure, feathers, animal by products and food waste from restaurants and grocery stores) when she was doing research for The Omega Diet, a book she co-authored with Dr. Artemis Simopoulos that explored the health benefits of the Mediterranean Diet. When she found this bit of information, it compelled her to dig further, and she started examining the scientific literature on the subject of how livestock animals’ diets reflect on the chemical and physical composition of their meat, milk and eggs, and how this relates to human health. What she found out astounded her, and caused her to not only write this book, and create the website, EatWild, but also to start speaking to ranchers, government regulatory agencies, consumer advocacy groups and supporters of sustainable agriculture. In this way, she took her message on the road to whoever would listen, and has been a large part of the newly arising movement of small grass-based farmers who are offering products with superior health benefits which are better for the environment to the American consumer.

While Robinson is a fine writer, especially when she is compiling the facts surrounding the unique chemical and physical properties of grass-fed products and their affects in the human body. I couldn’t help but be somewhat bemused when she claimed she didn’t understand why researchers in the pay of industrial farming interests never investigated the idea that what goes into a farm animal affects what comes out of it–the meat, milk and eggs. She claimed to be confused as to why any researcher who would investigate the feeding of stale chewing gum, complete with wrappers (she cites the sources–it is a real study and yes, Virginia, some dairy cows are fed chewing gum), would not take their research any further than noting that it seems to cause no harm to the animal and it does not cause the animal to lose weight or fail to thrive, nor does it deposit untoward amounts of aluminum (from the wrappers) in the muscle tissue of the animal.

Either Robinson is trying to be nice and give the benefit of the doubt to these researchers, or she is naive or she just doesn’t want to come out and say why no one in the CAFO industry wants anyone to research the compositional differences in the meat from animals fed on grass and those fed on whatever cheao crap CAFO operators come up with to feed their animals. They don’t want to budge from their party line of “meat is meat, eggs are eggs and milk is milk, no matter where it comes from or how it was raised” because to do so threatens their bottom line. If they ever were forced to admit that they were producing an inferior, often unsafe and unhealthy food product for the American consumer, they might as well fall on their butcher knives and admit that BSE is their own damned fault, and that they never cared for the health and well-being of their animals or the people who ate their products.

All they care about is the bottom line.

Other than Robinson’s seemingly naive ignorance of the possible motivations of meat, milk and egg industry officials who want the public to remain ignorant of the fact that what goes into an animal affects what comes out (any breastfeeding mother should be able to figure this out; think of all of the injunctions against foods and medications that mothers are given because these things come -through- the mother’s milk; if this is true for humans, then logically, it is true for cattle as well), my main criticism of her work is that she does not address the issue of whether it is possible to feed all Americans on pasture-raised foods.

This is an issue that not many authors address, but it is a question that really needs to be answered. While I disagree with the way CAFOs do business, and I refuse to support them with my money, I also recongize that I have the money and the time to seek out smaller, local producers whose farming methods are more in line with my own ethical guidelines.

Not every consumer is as lucky as I am. I live in an area that is blessed with local food producers whose vision of agriculture is one of sustainability. I also, as I mentioned, can afford the higher prices these producers charge for their products, but I recongize that not every American is able to afford what I can.

This -is- an issue. While I think that it is likely that as demand for pasture-raised products rises and more farmers enter into the marketplace, the price will come down, I also recognize that it will likely never reach the rock-bottom prices that CAFO’s can offer the consumer. (On the other hand, CAFO’s are terribly petroleum dependant–as oil prices rise, it is likely that industrial meat prices will rise as well. It may even be that at some point in the future, smaller, local producers may be able to compete directly with industrial producers on the basis of price.)

Most authors, including Robinson, duck this issue by not addressing it at all.

I think this is a shame–and someone, somewhere, -should- think about the fact that most of this better, healthier, local food, is not going to be eaten by lower-income people, but by those in the middle class and on up. While it is true that the middle to upper classes have always had access to better food than the poor, one could argue that in a supposed democratic nation like the United States, this should not be the case.

Other than that one glaring political flaw in the book, I thought it was a well-written argument in support for a more natural, sensible method of raising food animals, and is well worth the read. It is a great book to give to your parents, your aunt Sally or your co-workers when they ask you why you insist on eating grass-fed beef or lamb or pork. It is concise, simple to follow and persuasive, and includes recipes from grassfarmers in the back for how to cook their products in the most flavorful way possible.

It is also a good reference to have on hand to use in martialling your facts in order to effectively argue with skeptics, though I have to admit that much of the same information in the book is also available on the EatWild website, in their free articles section.

All in all, it was well worth the few hours it took for me to read it cover to cover.

Blueberry Navajo Fry Bread

When I posted about the Navajo Fry Bread this spring, I promised to experiment this summer with a variant that included fresh blueberries in the dough.

While the experiment was not a complete success, it was good enough to repeat, with some refinement.

First of all, I changed the recipe for the dough somewhat to reflect my recent attempt to replace as much refined grains with whole grains. So, most of the flour in the dough is a mixture of traditional whole wheat flour and white whole wheat flour, with just a very small amount of all purpose white flour. I also lowered the amount of honey, from five tablespoons to three, with no appreciable difference in flavor.

I also used the traditional lard in the dough instead of the oil I use in my regular recipe; the change was not noticeable, so I would say that one could choose whether to use a vegetable oil or pork lard based on personal preference and what one thinks of partially saturated animal fats vs. polyunsaturated vegetable oils.

The rising time of this dough was considerably longer than what I use in my regular recipe; I ended up starting the dough the evening before I meant to use it; the next evening, I made plain fry bread to go with bison and bean chili and calico salsa. I intended to knead blueberries into the other half of the dough to fry up for dessert, but no one was hungry after fry bread, beans and bison, so I put the dough back in the fridge and let it rise in the cold for one more night.

I got up the next morning, kneaded in the blueberries, shaped the little breads and fried them for breakfast.

I served them with honey, powdered sugar and cinnamon sugar for each person to sprinkle their bread as they saw fit or not.

The results were mixed: most of the breads fried just fine with the berries in them; one smallish bread that had probably too many berries for its size, which Morganna got, did not fry completely in the middle. The liquid from the blueberries seemed to keep the dough raw in the center in that one piece. It may also be that it was the last piece of bread to fry and I had turned the heat down, and the oil may have cooled off a bit too much.

Morganna also complained that the dough, on its longer rise, had become too yeasty to blend well with the blueberries; however, that will be easily combatted by simply making certain not to let the dough rise over a two day period and instead let it rise no more than 24 hours total.

Zak, Brittany, Donny and myself all seemed to find the bread to be good and ate it happily, so while I will not say it was a complete success, I think it is worth experimenting with again in the future.

The change in flours did not seem to affect the palatability of the bread, either plain and dipped in chili or with blueberries and eaten for breakfast in a negative fashion at all. In fact, the resulting breads were still light and fluffy on the inside, very flavorful, and crisp and lightly chewy on the outside. They tasted great, in fact, with very little all-purpose flour in them.

The blueberries were little nuggets of juicy sweetness that made a nice contrast to the light, fluffy interior, and those on the outside, caramelized slightly and were chewier, yet still contrasted with the thin, crispy crust.

Here is the modified recipe, taken from the original recipe posted in March.

Blueberry Navajo Fry Bread

Ingredients:

3 tablespoons honey

3 tablespoons lard (I think that you can use vegetable oil–the lard did not change the flavor or texture of the bread to my taste)

2 cups hot water (bathwater temperature)

1 tablespoon active dry yeast yeast (I use SAF)

2 cups whole wheat flour

2 cups white whole wheat flour

1 tablespoon salt

2 teaspoons baking powder

1-3 cups additional all purpose flour (I ended up using about 1 1/2 cups AP flour here)

1/2 pint fresh blueberries, washed and thoroughly dried, with stray stems picked off

Peanut oil for deep frying

Method:

Mix together honey, lard or oil, water and yeast. Allow to sit to proof yeast.

Put first four cups of flour, salt and baking powder into bowl and stir well. When yeast mixture is foamy and thick, pour into flour bowl and stir until it forms a thick batter. Add one or two more cups of flour, oil hands well and begin kneading to incorporate flour. Knead until the dough is firm and begins pulling away from sides of the bowl and pulls dough off of your hands.

Spray the inside of a large ziplock bag with canola oil, and put the dough in, then seal it up, leaving plenty of air inside. Put into the refrigerator and allow to rise for about twelve hours. Degas the dough by squeezing it and deflating it and let it rise again, preferably overnight.

When you are ready to fry, take the dough from the refrigerator and open the bag slightly, and allow the dough to come to room temperature. When it is warmed up, on a floured countertop, knead in the fresh, washed and dried blueberries gently. Try and get them evenly distributed through the dough and try to not break too many of them.

Then, roll the dough into a long rope and cut into 12 equal pieces. Roll each into a ball, and flatten into a disk that is slightly thinner in the middle and fatter on the edges. Make certain there are not too many blueberries in any pieces–8 or so is about the maximum you can have and not have soggy dough in the middle.

Flour them sparingly, and keep the ones you are not working with covered to keep the dough from drying out.

Heat oil in a wok to frying temperature. (The easiest way to test if the oil is hot enough is to use a bamboo chopstick. If you put the tip of the chopstick in the oil and bubbles form around it immediately, the oil is hot enough. If it takes a minute or so for them to form–it is still too cool. Wait a minute and try again.)

Slide each disk gently into hot oil and cook about 1 1/2 minutes per side, or until nice golden brown. Allow to drain on paper towels and serve hot.

You can sprinkle them with powdered sugar, cinnamon sugar or drizzle them with honey. Or, you can do like I did and eat them plain.

A Celestial Pie With Less Sugar and White Flour

A few weeks ago, I had a routine glucose tolerance test that pregnant women go through. The results were borderline high, so I went back for a three hour glucose tolerance test and while it came back with four normal readings and one high reading, my doctor suggested that I avoid eating much in the way of refined sugars and refined white flours, white rice and pasta.

Now, I won’t eat whole wheat pasta, beacuse I really think it tastes like wet cardboard, but the fact is, I like whole grain breads better than white breads, and I prefer brown rice to white. (That sentiment on rice is not shared by Zak and Morganna, so in deference to them, I bought a small rice cooker, and when we eat basmati or jasmine rice, I will make a small amount of it whole grain for myself, and cook white for the two of them in our larger rice cooker. It seemed a logical solution.)

The refined sugar isn’t too much of a problem, as I don’t bake or crave sweets too much. But, I had bought three pints of blackberries in order to make a pie, and was stuck with the problem of how to make a pie without using a bunch of sugar and white flour.

Remembering the cider-sweetened apple pie which was such a hit in the fall, I decided to do a juice-sweetened blackberry pie.

However, it is not so simple to find blackberry juice as it is to find apple cider.

What I did find, on the other hand, was a product from Italy called Fiordifrutta–an organic Italian preserve that consisted simply of blackberries, apple juice and apple-derived pectin. It is smooth–obviously, it has been cooked down, and the seeds have been strained–and it is intensely blackberry-flavored. So much so, that it tasted like thousands of berries went into the making of one teaspoon of that stuff.

It was also considerably sweeter than the berries I had, which were more sweet-tart in flavor.

So, I rinsed the berries, and drained them, and set them in a bowl, and in order to get them to release their juice, I sprinkled them with 1 tablespoon of raw sugar–a paltry amount, considering that most recipes call for a half cup to a cup of it. One tablespoon had them releasing their juices after about an hour and a half, in just as copious an amount as more sugar would have yielded, though not as quickly.

I then mixed in some rosewater, a 1/3 cup of the preserves, and 3 tablespoons of cornstarch.

As for the crust–I used the same recipe I always do–the wonderful lard-butter crust, but instead of using all purpose flour exclusively, I used half that and half white whole wheat flour. I also used the 1 tablespoon of raw sugar in the crust, but next time, I will leave that out as well, because the white whole wheat adds a nutty sweetness that I think will easily take the place of the sugar.

The crust dough handled the same as if I had used all purpose flour exclusively. It was no harder to roll out or cut than the usual recipe is.

In fact, it was so easily handled, I decided to have fun with the crust, and instead of making either a lattice top or a double crust pie, I would cut motifs out of the dough and scatter them over the top of the pie. Because blackberries bake up such a dark, velvety purple, I decided to use my two sets of “celestial” cookie cutters and make a series of stars and comets to dance over the fruit in a shining array.

The touch of whimsy made the pie especially impressive to Morganna, Brittany and Donnie–the young folks really liked the idea of having a whole Universe in a pie.

What made me happy was that no one knew anything of my substitutions–the pie tasted just as good as the less-healthy ones I had made in the past. The filling, in fact, was particularly delicious, much more fruity in flavor than traditional fillings, and in fact, was praised vociferously for being excellent. It also, as you can see in the photograph below, held together remarkably well–the pectin in the preserves helped hold it together during baking and made a firm filling that sliced well, but which wasn’t goopy or too jelly-like.

I suspect that this method for making fillings will work with other fruit-based pies. Some pies I could use the concentrated juices to sweeten them–I will try that for the fruits for which I can find concentrated juices. I could have cooked down a portion of the berries to make a concetrated juice myself, but I thought that the addition of pectin might make a nice filling and I was correct. Besides, the preserve tasted so intensely “blackberry” that I couldn’t resist using it in the pie.

I just can’t wait to try it on my whole wheat toast next.

Fruit-Sweetened Blackberry Pie

Ingredients:

5 cups fresh blackberries

1 tablespoon raw sugar

1/3 cup blackberry Fiordifrutta (I found this at the local healthy food store, but I have seen it in specialty stores before)

1 tablespoon rosewater

3 tablespoons cornstarch

Method:

Rinse and drain blackberries until thoroughly dry. Put in a bowl and sprinkle with the sugar, and cover. Allow to sit for an hour and a half until it releases a good quantity of juice.

While this is going on, go to my recipe for the lard-butter crust, and follow the instructions there, except substitute half of the all purpose flour with white whole wheat flour, and leave out the sugar. Roll out the bottom crust as called for in the instructions and lay it in the pan and trim it as directed.

Mix together all of the filling ingredients and pour into the trimmed bottom crust.

Roll out the top crust as directed in the recipe, but instead of laying it over the pie, cut out a bunch of leaf, star, heart or other shapes with small cookie and pastry cutters, and array them over the pie, touching along the edges.

Make a fluted edge to the bottom crust, and bake pie as directed in the crust recipe instructions.

Allow to cool nearly all the way before eating–otherwise the filling will not hold together to be served, and the pie won’t look as pretty cut as it could.

Around the Food Blogs: The Ethics of Recipe Writing, Publishing and Blogging

Meg of Megnut posted an article that appeared earlier this year in the Washington Post about recipes and copyright, and Kate of the Accidental Hedonist wrote a bit about it on her blog this week. When the article came out, I remember writing about it on The Paper Palate, back when I was editing that blog, and I think that the issue is pretty clear cut and simple.

Legally speaking, a recipe, per se, cannot itself be copyrighted in the USA. The list of ingredients and amounts cannot be copyrighted, but the literary expression–that is to say–the wording, grammar, syntax and sentence structure used to convey the method of putting those ingredients together is seen as a unique intellectual property akin to a poem or a short story, and thus, -can- be copyrighted. An entire cookbook, as a literary product, is copyrighted, but each individual recipe, most particularly, the ingredients list, is not.

What does this mean for us food bloggers?

Well, it means that if you read a recipe in a book, newspaper, magazine or blog, and copy the ingredients list exactly and then just rewrite the instructions for putting the recipe together in your own words, then technically, you are not “stealing” copyrighted material. You are then under no obligation to say where you got the recipe in the first place.

However, legality is not the same thing as ethics. Plenty of unethical actions are, or were at one time, perfectly legal. Slave-owning, for example, was, at one time legal in the US. That didn’t make it morally or ethically defensible, it just meant that it was legal.

No, slave-owning is not the same thing as taking a recipe that someone else wrote and presenting it as one’s own-I just used the first example off the top of my head of an action that was at one time legal, but was, in my opinion, never ethical to make my point that the law of the land is not the same thing as personal ethics.

As a blogger, I find it very important to have a strong sense of personal ethics that are not limited by the letter of the law.

Why?

Because I work hard writing my blog, and as a writer, I don’t want anyone else presenting my work as their own. I am sure that every other writer in the world understands this, and I am pretty certain that most readers do, too. It sucks to have one’s work co-opted by someone else who then takes credit for the creativity that it represents.

So, here is my take on the -ethics- of the issue of recipe writing, publishing and blogging:

If I present my own recipes to my readers, all free of charge, and give them away with the caveat that I only want them to tell folks where that recipe came from–in other words, pass down the story that tells the origin of that recipe–because that is the fun part of this blog writing business–storytelling, then it behooves me to give the same courtesy to all other recipe writers.

That means, that if I am inspired by a recipe I read in a book, newspaper, magazine or blog, and I write about it, I am obligated to tell the truth of the origin of the recipe, as that is part of the story of its origin. That way, I am not taking credit for someone else’s work.

What happens if I change the recipe considerably, however, before I blog about it?

This is a good question, because really–I seldom -ever- cook a recipe as written, no matter who wrote it. Madhur Jaffrey can write it, and I don’t care, I will still change it. It is just how I am. So, if I change it, do I still feel obligated to tell where it came from?

Of course. It is still part of the history of the recipe. It is part of its origin. Personally, I feel obligated to tell what inspired me to make a recipe, even if I change it beyond all recognition.

Why?

Well, I think it is because at heart I am a storyteller, and because I was trained as a journalist, and I have an interest in the history of food.

As a storyteller, I want to tell folks why a recipe is interesting, and why they should cook it up in their own kitchen. Sure, the food is tasty and all, but I don’t read cookbooks just because I want to read about what food tastes like. That is secondary–I want to know the -story- behind the recipes. What compelled someone to make up this recipe? Where did it come from? Who made it first? Who passed it down to whom, how and why?

As a journalist, I remember having it drilled into my head that we must be factual, and we must, above all, tell the truth. I mean, I tend to be a bluntly honest person anyway, but that has been bolstered over the years of doing straight news reporting, which is all about “just the facts, ma’am.”

And as an armchair historian, I think that food and recipes are repositories for human culture that are often overlooked by the sorts of historians who see human history as a series of wars, conflicts and names and dates. Yes, yes, all of that is interesting, and is contains the material for many a fine story, but I like to look for the story of humanity in different places–like the kitchen. And so, when I present recipes, I like to be very thorough in my description of their historical pedigree, because I think that I cannot possibly be the only person of a historian’s bent who finds this stuff fascinating, and maybe, in my own little way, I am helping to document a little bit of 20th-21st century kitchen history.

So, there we are–my thoughts on the ethical considerations of recipes, writing, publishing and blogging.

What are other folks’ feelings on the issue?

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.