Weekend Herb Blogging: Curry Leaves

I first came across curry leaves in Columbia, Maryland, in an Indian grocery store. Set in the cooler, next to quarts of yogurt and packages of paneer were these glossy almond-shaped, deep green leaves, set alternately on gracefully curved narrow stems. They looked somewhat like bay leaves, but they were not leathery enough in texture–these were soft and very thin. When I opened the cooler an odd, strong musty smell overtook me. It wasn’t unpleasant at all, but quite compelling.

I reached in and took out one of the bags and held it to my nose.

Yes, the leaves were the source of the smell.

But I had no idea what they were, only that I liked the smell of them. I shrugged and turned to put them in my basket, along with masoor dal, black cardamom and fresh chiles. Next to me was a tiny older woman in a blue and gold sari. Her long white hair was braided down her back into a rope as thick as my forearm. She smiled up at me and nodded. “You like them?” she asked.

I smiled and said, “I like the way they smell, but I don’t know what they are.”

Her smile deepened and her eyelids crinkled. “Kadhi patta,” she said. “You would say, curry leaves.”

I nodded, excited. “What do you cook them with?”

“Everything,” she answered. “Everything!” Glancing down at my basket she nodded at the masoor dal. “With dal, with eggplant, with potatoes. Everything.”

I nodded avidly, urging her on.

“You heat up your pan, and put the oil in. Then, a handful of curry leaves. Let them curl up and get brown and crisp, and their flavor goes in the oil, and then on everything you cook in it.”

Her daughter came up to her; it was apparently time to leave. Bowing to her, I thanked her profusely, and we waved goodbye cheerily, as I turned to my shopping and she bustled after her daughter and grandchildren.

Curry leaves are from the plant, “Murraya koenigii,” which grows as a shrub or tree all over South India. I am told that the young plants are easy to grow in the house; I will have to try this, though while I have a wonderful green thumb when it comes to outdoor plants, my indoor plants sometimes fall prey to munching cats or my own forgetfulness.

As my unnamed benefactress at the Indian grocery all those years ago said, curry leaves are used to enhance many different curries in South India. Monisha Baradwaj, author of The Indian Spice Kitchen, which is one of my favorite reference cookbooks for Indian food, says that while Northern Indians use fresh mint with a free hand, the people in Southern India use curry leaves with joyful abandon.

I have been using them more and more, and whenever they are available, I buy them up greedily. When I have too many, I will freeze them. They lose some of their fragrance, but not all of it, and I use them especially for dals after they are frozen to good effect.

Most of the time, curry leaves are removed from the dish they are cooked in prior to eating them, but I also know of recipes where they are eaten. I have eaten them with no ill effect–they are a little bitter, but then, I am fond of bitter melon, so a little, slightly bitter leaf is nothing to me!

The recipe I am presenting today is a quickly fried curry of chicken and potatoes that uses curry leaves, ginger, chiles and black pepper as the main flavorings with a single black cardamom pod, cloves, and coriander to round out the masala. At the end, I added two teaspoons of tamarind concentrate to give the curry a liltingly sour finish which complemented the curry leaf musk and the pepper, ginger and chile heat perfectly.

Curry Leaf and Ginger Chicken

Ingredients:

1 teaspoon black peppercorns

1 tablespoon coriander seeds

1/4 teaspoon turmeric

5 cloves

1 black cardamom pod

1 tablespoon coconut oil

2″ cube fresh ginger, peeled and cut jullienne

4 red Thai bird chiles, thinly sliced on the diagonal

handful of curry leaves taken from the stem

1 whole boneless skinless chicken breast, trimmed and cut into 1″ chunks

8 fingerling potatoes, boiled in salted water until nearly cooked through, then drained and cut into chunks

1 cup water or chicken broth

2 teaspoons tamarind concentrate

salt to taste

small handful of cilantro leaves

Method:

Make your garam masala: Grind the first five ingredients together into a fine powder and set aside.

Heat oil in a wok or heavy bottomed skillet until melted and quite hot.

Add ginger and chile, and stir fry for about thirty seconds, or until it just becomes quite fragrant. Throw in the curry leaves and stir. They will pop, fizzle and crackle as their juice is released into the oil. Stir carefully until they begin to curl up and turn brown–about thirty seconds.

Add chicken in a single layer, and leave still to allow it to brown a bit on the bottom. Sprinkle the masala over the chicken and as soon as you smell the chicken browning, begin stir frying. Add the potatoes, and keep stir frying. When most of the pink from the chicken is gone, add the chicken broth or water, and turn the heat down, and allow it to simmer to cook the chicken and potatoes through.

When they are cooked through, turn the heat up, and allow the sauce to reduce until there is just a tiny bit of it left. Add the tamarind concentrate, sprinkle in salt to taste, and stir in cilantro leaves, then serve with steamed basmati rice. (Before serving, you may remove the curry leaves if you wish.)

Zak’s Favorite Curry: Mattar Paneer

Last week was the first time I ever made Zak’s favorite curry, mattar paneer, which is Indian cheese with peas.

Now, I love Zak, very, very much. But I never bothered with his favorite curry, because I never really much liked it myself, and here is why:

I really dislike peas.

Or, rather, I used to really dislike peas.

When I was a little girl, peas came from a can, and often had little pearl onions in them. They were khaki colored, mushy and tasted of tin, onion and…something musty, I don’t know what. Something unpleasant. They made my stomach wiggly, and not in a good way.

So, I used to try to avoid eating them. I’d try and hide them, and when that didn’w work, I’d try to say I wasn’t hungry anymore, but that never worked, because my mother was the sort who used to make me sit at the table until I cleaned my plate. Which meant that I spent many an evening staring balefully down at those wretched, ugly smelly green things as they congealed on the plate.

Finally, I would spoon them into my mouth and swallow them whole, wincing with each bite, and gulping much milk down in between in an effort to kill the taste that clung to my tongue in an evil attempt to make my stomach threaten with mutiny.

It was a supreme effort of will not to spit them out on my mother’s feet, but I managed.

Later, I would just take as small a portion of them as possible, and swallow them whole so I would be left alone on the issue of the overcooked, mushy little leguminous balls if ick.

In later years, I discovered that I actually liked peas raw, and snow peas were a revelation in crunch and sugary flavor. Sugar snap peas are amazing when barely cooked, although my mother insists on overcooking them to a flaccid, insipid state where most of the flavor is dissolved away into the boiling water.

But, it is yet true that I have a yet abiding aversion to peas in most forms.

And frankly, I have had mattar paneer in restaurants, and while it was good, it never blew me away. I never wanted to eat much of it, though Zak could make a meal of nothing but it, rice and naan easily. Which is weird, because he generally prefers meat to vegetables of any sort.

Well, last week, after I picked up some paneer at the new Indian market in Columbus (which is named Taj, not Patna’s–I now know why I remembered it as Patnas–that ws the name of one of the grocers I went to Maryland, and it was set up very like Taj’s), I resolved to make mattar paneer.

Paneer is a firm, very fresh cow’s milk cheese that is usually made at home by heating whole milk and then treating it with a weak acid, such as lemon or lime juice to get it to coagulate. Once the curds form, they are poured through cheesecloth, the whey is squeezed out, and it is left to drain overnight. A weight can be left on it to press it into shape, and to facilitate the removal of most of the whey. (For a wonderful post on how to make paneer at home with great illustrations, check out Indira’s recipe at Mahanandi.)

I made paneer several times in culinary school, but as I don’t have cheesecloth at home, I decided to take a chance on some packaged paneer. The brand I bought, Nanak, turned out to be very good indeed, and I would recommend it to those who don’t want to take the time to make their own cheese at home.

Zak is used to the creamy tomato-based sauces served with mattar paneer in restaurants, so I based the recipe on Neelam Batra’s Tomato Cream Sauce with Cardamom and Cloves from her cookbook, The Indian Vegetarian. As I did not have fresh tomatoes that are worth the name tomato, I used crushed canned tomatoes instead, and I changed the spicing considerably to reflect the flavor of the mattar paneer at Akbar’s in Columbia, Maryland, the restaurant where Zak first fell in love with the dish. Batra’s version was much hotter with chiles; the chef at Akbar’s however, always spiced the sauce so that there was a light heat that crept up on the diner about halfway through dinner.

I also have to admit to using less cream than Batra advised, and a bit of milk instead, so the end product would not be so killer-rich as it could be.

I would have liked to have served the peas in a less cooked state, but Zak preferred to have them simmered in the sauce until they softened. I was reluctant, my mind and stomach clenching at the remembrance of the over-cooked peas of childhood, but I was pleasantly surprised to find that the flavor of these mattar were completely different. The sweetness of the well-cooked peas had entered the sauce, and the peas themselves were not mushy, but simply meltingly delicious.

Altogether, it was a very, very pleasant surprise to me.

And what did Zak say?

“I believe this is the best mattar paneer I have ever had,” he told me after his second bite.

That is incentive enough for me to make it for him again.

Mattar Paneer

Ingredients:

5 large cloves garlic, peeled and sliced

1 2″ cube fresh ginger, peeled and sliced

1 red Thai bird chile

1/2 teaspoon aleppo pepper flakes (aleppo is a mild chile from Turkey–optional–I get it from Penzey’s)

1 teaspoon black peppercorns

1/2 teaspoon cardamom seeds

1 tablespoon coriander seeds

10 cloves

1/8 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 tablespoon paprika

2 tablespoons butter

8 ounces paneer cheese cut into 1/2″ cubes

1 14 ounce can crushed Muir Glen Fire Roasted Tomatoes

1/2 cup milk

salt to taste

3/4 cup heavy cream

2 cups frozen peas, thawed

large handful fresh mint leaves, chopped roughly

Method:

Grind together the garlic, ginger and spices into a thick paste.

Melt butter in a heavy-bottomed skillet, and when it foams, add paneer. Add spice paste and cook, stirring, until the spices are very fragrant and the paneer is beginning to brown. Turn the paneer, and keep stirring. Add the tomatoes adn milk, and stir. Turn down the heat and simmer for about ten minutes. Add the heavy cream and salt to taste. Add the peas, and turn heat down to very low and simmer slowly for about an hour or so.

After it has cooked for an hour, put a lid on the pan, turn off the heat and let it sit for another hour or so. When you are ready to serve, reheat the curry to a simmer, adding a bit more milk or cream as necessary to keep it from reducing too much.

Just before serving, stir in mint leaves.

Not surprisingly, this is even better heated up the next day. You may have to add more milk to the sauce to think it out so it will reheat properly.

Peppercorns, Ginger, Soy and Sugar: A Meditation

Some evenings, the simpler the dish, the better.

Tonight is one of those times: too tired after being struck forcibly with a bit of unsettling news, I did not really want to cook, but I must.

The lurching miasma in the pit of my belly insists that it be so.

Into the kitchen I walk squaring my shoulders, pulling back my hair, tying on my apron.

My body moves into the dance it knows so well, gathering ingredients, setting down prep bowls, creating the mise en place.

The simple rhythym of cookery has the power to sooth a trembling soul, and as I take up my knife, my hands fall into their places and my heart beats more slowly, and my breathing deepens.

Crushing peppercorns in a mortar and pestle is a prayer. Feeling each grain give way beneath the time-worn stone in my hand, I inhale deeply, taking in the healing breath of the spice, sharp as the sunlight on the west coast of India where it was grown. The heat of the ginger tingles in my nostrils, the two strong scents weaving themselves into my consciousness, warming the cold place where fear dwells.

Two tiny Thai chiles, scarlet as cardinal feathers, are sliced into fine slivers, and sprinkled among the grass-fine strands of ginger.

No garlic.

Nor onion.

Not tonight.

The asparagus, shipped from California, so completely unseasonal, jostled my heart, and a twinge of guilt pinched my awareness, but I let the knife move with whispering precision as I cut it on the diagonal. No, it was not local, but I had seen it, and it was beautiful, stalks of creamy jade shaded to white and violet at the ends, with tightly budded crowns of forest green and purple. It was beautiful and fragrant, and I had to have it, and so, it came home with me. I had felt a pang of longing for it, and so now, it was here.

Release the regret. It is done now.

Guilt slides away, drifts past me on the current of air stirred by the open window.

All that is left is the meat.

The gaping maw of my stomach twists, and churns as I open the bag holding the piece of tenderloin left from Christmas dinner. I had thawed it this afternoon, but the scent of it hits me and I feel my head spin in a reel.

Concentration is broken, waves pull me forward and back and I feel myself shiver and twist in the grip of the animal scent of meat.

I swallow hard, force my eyes to focus and return to my discipline.

My shoulders are square.

I can do this.

I can. And I do. And the rhythym of the knife soothes my soul, though the damp blood scent still threatens to roil into my consciousness in a black cloud of dank sorrow.

Life feeds on life, I whisper, as the knife flashes in my hand, like a silvery sliver of light.

Life feeds on life, I whisper as I watch the muscle of what was once a cow fall into slices beneath my hands.

Blood tinges my fingers.

Life feeds on life feeds on life feeds on life.

Nothing is wasted in this ecosphere, this planet. I will eat this cow, this bit of cow, and take it into myself and it will become myself, and then, when I fall, like the cow, I will sink into the earth, and be fed upon. My body will crumble, will feed the worms, they will make of me soil, and I will feed the grass, the trees, the deer.

And the cows.

Life feeds on life.

Wine, heady with richness, pours in an amber ribbon over the meat. Soy sauce, dark and rich, redolent of rivers I have never known, follows, and my fingers take up the meat and massage it and toss it with cornstarch, and soy sauce and wine.

Slippery soft as mud from the riverbank, the marinade coats the beef and it is done.

I set down the bowl beside the wok.

My feet move in a dance they know, have known forever it seems. Back and forth, as my hands fetch the mise en place– every small bowl, every bottle, every ingredient and utensil, and settle them beside the altar.

By the altar, where the fire will come.

In one quick laughing whoosh, blue flame, pure as a mad summer sky, engulfs the bottom of my wok, and the scent of hot iron fills my thoughts.

My mind is as empty as the wok. I am at the beginning place, and there is no time to think.

No time to worry.

Nor grieve.

We are the beginning place.

And we.

Must move.

A thread of white smoke spirals up from the wok, and my hand pours the oil.

Once. Twice. Thrice around the wok.

And it is done.

In a moment, the oil shimmers in the heat, and the wok exhales, and I inhale, taking the spirit of the wok, of the stove, of the fire, of the altar, into myself.

Ginger and chile fall into the oil first, then the peppercorns, ground into a fine powder.

The exhaust fan roars like a fell beast in my ear, but I cannot hear it. I am watching the fire, smelling the ginger, chile and and pepper as they braid their essences into a single entity.

The meat is next. Scooping it up with the wok shovel, I lay it tenderly into the hot oil, spreading it into a thin layer and leave it, though it hisses and gurgles and sighs. I leave it to cook, until I smell the sear of beef on iron, a brown scent like the earth after a rain, like clay pierced by a plow.

Then, I my arm swoops like a hawk stooping, and the wok shovel flashes and sings against the wok. It strikes as it stirs the meat, and the wok calls like a bell, like a gong.

This is prayer.

Most of the red is gone on the meat. Soy sauce flows. Wine joins it, and steam clouds my vision, wreathes my face.

Finally, the verdant asparagus that I coveted goes in, and the green deepens to the color of new spring grass, as I stir and stir and stir.

Sugar rains down from on high in a sparkling hail of pale gold.

A drizzle of sesame oil seals the contract, ties the loose ends of the flavors together, makes it whole.

It is done.

My stomach yawns with hunger, and the sick twisting is gone. Banished by the work of my hands, the path walked by my feet, it retreats to a darkened corner, to hide and wait.

But I care not. Peppercorns, ginger, soy and sugar have done their magic, and transformed a few ingredients into a revelation.

Asparagus Peppercorn Beef

Ingredients:

3/4 pound tenderloin cut into 1/4″ slices, then cut into narrow shreds

2 tablespoons shao hsing wine

2 tablespoons aged soy sauce

2 1/2 tablespoons cornstarch

3 tablespoons peanut oil

3″x1″ piece fresh ginger, peeled and cut into very thin slivers

2 red Thai bird chiles thinly sliced on the diagonal

1 teaspoon black peppercorns, freshly ground

1 pound asparagus, cut into 1″ pieces on the diagonal

1 tablespoon shao hsing wine

1 tablespoon aged soy sauce

2 tablespoons raw sugar

1/2 teaspoon sesame oil

Method:

Toss beef with wine, soy sauce and cornstarch, and allow to sit for at least fifteen minutes.

Heat wok until a thin ribbon of smoke appears. Pour in the oil, heat until it shimmers. Add ginger, chiles and ground black peppercorns. Stir and fry for about two minutes, or until quite fragrant.

Add beef gently to the wok, spread it into a single layer and allow it to brown on the bottom for about a minute or a minute and a half. Start stirring and stir fry until most of the red is gone from the beef. Add the second amounts of wine and soy sauce, then sprinkle with sugar.

Add asparagus and stir fry until beef loses the last of the red color, and the asparagus brightens in color. Drizzle with sesame oil, and serve with steamed rice.

Birth of a Blog Event: Spice Blogging

So, I have been reading about, cooking with and thinking about spices for, well a long time now. In terms of this blog, it has been a couple of weeks or so since I have been expressing my “spice obsession,” but in truth, I have been fascinated with those elusive, fragrant and delicious little nuggets since I was a child.

I grew up eating fairly bland food. People’s spice racks in my world were often more decorative than function, and were filled with herbs and spices that were like so much barely-scented dust. About the only time one saw spices other than black pepper being used in my family was at Christmas, when the “sweet spices”–nutmeg, allspice, cinnamon, cloves and mace came out to play.

Other than that, and the very sporadic flirtation with chili powder, curry powder and paprika (which almost always used as a coloring agent or a garnish, not to flavor the food), spices were not known in the world of my childhood.

But I always read about them and dreamt of them. I liked the smell of them.

I used to go through people’s spice racks as methodically as I went through the drawer of my Gram’s vanity where she kept her perfumes. I would peer at the bottles, open them one by one and sniff them–spices and perfumes, both.

This got me into trouble, because in my mother’s world, a kid isn’t supposed to be nosing into people’s cabinets, drawers or spice racks.

But I was intensely curious. And I wanted to know why, if spices were so important that they sent Columbus on his fateful voyage, and fuelled the resulting “Age of Exploitation–er, I mean, Exploration,” then why were they so little in evidence in American and European food in modern times?

Was it true that Medieval people were covering the taste of rancid meat with spices? (Nope–that is largely a myth, btw. There are lots of myths passing as truth in the realm of spices.) Was it true that the Romans ate food that would numb the tongue of a modern person? (Another myth.)

And if it was all true, then why didn’t we eat spices today? They smelled good, so why did we only use them in baking sweets?

A question for the ages.

So, let me get to the point here.

The point is this: spices were once powerful agents of social change in the West. Wars were fought over them, and people used to trade vast amounts of gold for them. People went sailing off to God-Knows-Where (that’s a real place, you know–just north of Where-The-Hell-Are-We?) in order to find them.

But now, in the West, they are mere shadows of their once glorious selves.

However, their stature is once again climbing, due in large part to Westerners’ newfound appreciation for the foods of the East and the New World.

The folks of the Indian subcontinent never lost their love of thier native spices. Nor did the Thais, the Chinese or the rest of the folks in Asia. The natives of Mexico and South America loved thier chiles, and still do, so when all of these folks started immigrating into the West, they started bringing their spices and other goodies along with them.

Now, I can walk into a Krogers grocery store here in Appalachian Ohio, and pick up a big ole industrial-sized bag of chile peppers grown in Mexico along with a big sack of mustard seeds from India.

This just did not happen thirty, twenty, hell, even ten years ago.

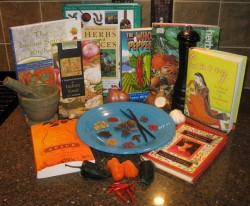

Globalism kicks serious culinary butt. Or, at least it does in my world, because I am no longer deprived of spices. A look into my pantry should tell folks that. I have tons of them, just laying around. My cabinets smell good, and my foods taste good. I feel like a very rich woman indeed, knowing that I can just reach into my cabinet and put as many peppercorns as I want into the grinder to season my stew.

So, I want to start a blog event to celebrate spices.

And that is where I need the help of you, my readers. Because blogging events are a community-wide thing, I want to ask your advice: how do y’all think I should go about this?

Should it be a weekly, “sister” event to Kalyn’s Weekend Herb Blogging, where participants post about a different spice each week and give us a recipe? Or should I make it more like Meena’s From My Rasoi, where it is a monthly event, and I have a loose theme for everyone to work with, so that it is a little more challenging?

What do you all think?

And one more thing: the definition of a “spice” for this event will be this one:

“A spice is the root, bark, flower, fruit, bulb, rhizome or stalk (or part thereof) of an aromatic plant in either fresh or dried form that is used to flavor or scent food or drink, as a perfume or a medicine.” (An herb is the leaf and/or soft stem of an aromatic plant that is used for the same purposes.)

Now that you know what I am about, what do you guys think? Would anyone like to participate in this sort of event, and how do you think I should structure it?

I will tend to

Freegans and Vegans: Where’s the Love?

Freeganism is in the news again, this time in the UK, and so I have had a flurry of links to the essay I wrote on the subject a couple of weeks ago. This renewed interest in the subject has spurred me to revisit it with a few more of my thoughts.

When I wrote my essay entitled, “Freeganism: What’s Up With That?”, one aspect of the freegan philosophy I found to be most curious, yet could not successfully work into the the post, was their intense hostility towards vegans who did not embrace the freegan lifestyle of consuming products gleaned from dumpster-diving.

While I have sympathy with the freegan core beliefs that the immense waste in our society is a cause of ecological, economic and social ills, I still stand against the means by which freegans attempt to redress the issue. I still very strongly believe that their “political statements” and “lifestyle choices” do little to assuage the damage caused by capitalist society and instead, they benefit directly from the waste generated by the industries they revile. I also do not share their very dim view of vegans, which I find to be strange, since many self-described freegans are also vegans, and in fact, the very name by which they call themselves, was coined as a play off of the word, “vegan.”

I should, of course, define what veganism is, before I continue.

Wikipedia defines veganism as “a strict form of vegetarianism, consisting of abstention from the consumption or use of all animal products, including eggs and dairy products, as well as articles made of bone, leather, feathers, mother of pearl or other materials of animal origin.”

In short, vegans are people who do not consume products that are non-plant in origin (including eggs, dairy, and honey), and many of them do not use or wear items made from any animal products, such as wool or leather.

The reasons for adhering to such a diet or lifestyle are myriad, but most of them boil down to a strong ethically-framed belief that the consumption of animal products involves cruelty to the animals, even if the animal is not killed to obtain the product. Many others are vegan for reasons of health, citing lowered cholesterol and blood lipid levels as the result of a vegan diet, while others become vegan for environmental reasons, stating that raising vegetable matter for human consumption uses fewer resources and results in less environmental degradation than intensive animal farming. Others note that if fewer humans ate meat, then more plant-based food would be available for humans to eat, and the result would be less issues of starvation and hunger in the human population.

These ethical reasons may or may not arise in conjunction with spiritual or religious beliefs, though there are some vegans who claim to be more spiritually aware as the result of not eating meat. Various religious beliefs around the world involve vegetarianism in several different forms as a means of spiritual purification and as a physical acknowledgement of the “oneness” of all life, including animals.

So, really, what’s not to like?

Well, if you are freegan, apparently quite a bit.

In an essay entitled, “Veganism,” author Adam Weissman states: “Usually, the question of animal oppression is approached only in terms of compassion and prejudice: animals are exploited and destroyed, bands like Earth Crisis would have us believe, simply because we see them as subhuman and are willing to abuse them in order to satisfy our greed. I suspect that the problem runs much deeper than mere cruelty and avarice. Under capitalism, it’s not just animals that are exploited—it’s everyone and everything from farmlands and forests to farmhands and grocery clerks. The oppression of animals is just a little more obvious to us because it involves the murder of living things; but it’s not just animals that have been enslaved and transformed by our society, it’s everything, ourselves included. Without an understanding of how and why our social/economic system drives us to seek to dominate and exploit everything, we will not be able to alter the way animals are treated in any significant or long-lasting way”

He continues, “When I walk through the aisles at the supermarket, looking at all the products for sale around me, perhaps I can tell which ones are manufactured from the exploitation of animals, but I can’t tell which ones—if any—are manufactured without exploiting anyone or anything….So the idea that you can be sure that your dollars are not financing anything inhumane or destructive just by examining the ingrediants of a product and ascertaining that it includes no animal products strikes me as absurd. There are a thousand other kinds of oppression, just as outrageous as animal oppression, that keep the wheels of our economy turning, and there is no reason to be less concerned about any of them than about animal oppression.”

From reading Weissman’s words, it is clear to me that he feels that vegans are not “radical” enough to satisfy his own beliefs regarding how best to stop the exploitation of animals. When I was in college, I noticed that a lot of the more radical, hardcore fringe groups dedicated to social change on a grand scale suffered from a lot of infighting, when they could be banding together in order to more efficiently affect real changes in society. Much of the bickering involved minutia that revolved around which group or individual was the most “radical,” which essentially created a situation where marginalized groups fought to marginalize each other further–a most illogical activity.

This is what Weissman’s diatribe against vegans and veganism feels like to me–a very far-fringe individual pointing a finger at a less-fringe (yet still marginalized) social group and accusing them of siding with “the man.” Or, in this case, the “capitalist pigs.”

Of course, Weissman has more to say on the subject. He never seems to lack for words.

“In the meantime, rather than practising veganism, I practise “freeganism.” I know that as long as I participate in the mainstream economy, whether I am buying vegan or non-vegan products, I am supporting the corporations which represent world capitalism. So rather than just buying animal-friendly products, I try to purchase as few products as possible….Anything I can get for free at the expense of the exploiting, oppressing capitalist system is a strike against that system, while purchasing vegan food from Taco Bell (which is owned by Pepsi Co.) is still putting money into the hands of an oppressive, exploiting corporation. I live off of whatever resources I can scrounge or steal from our society, trying to avoid animal products when I can, but concentrating above all on keeping my money and labor out of of their hands….A willingness to pump money into the mainstream economy, which is responsible for the oppression of animals and humans and the destruction of the environment, through consumer spending…is not compatible with the professed goal of most people who follow a vegan diet, which is to end the exploitation of animals.”

In other words, vegans don’t do enough to end capitalism, which is the root cause of the oppression of animals, because it is the root cause of all oppression. (I cannot help but wonder if Weissman believes that capitalism was extant in the Neolithic period when the domestication of farm animals began. Once again, as I noted in my first essay, his grasp of food anthropology and human prehistory is fundamentally flawed.)

His argument against veganism as being mired in consumerist society, however, is flawed, because while he hopes to create a new and different economic system, one that is not based upon oppression, he refuses to acknowledge the existence of alternate means of food aquisition beyond buying from the corporate-owned grocery stores.

No mention is made of buying directly from small, local farmers through CSA’s (consumer supported agriculture), farmer’s markets or local co-op stores. Nor does Weissman mention supporting small local producers of tofu, or locally-owned bakeries. Supporting local farmers and small food producers would go a long way providing an alternative to the current corporation-dominated economy, but these possibilities are ignored, even though many vegans and omnivores participate in the support of these businesses.

Instead, Weissman proudly proclaims that he sometimes steals in order to “stick it to the corporations.”

That certainly sounds ethical, doesn’t it?

Why does Weissman refuse to recognize the viability of smaller, local farmers and food producers as a means by which to change society into a more ethical, less cruel and oppressive one?

That may be because Weissman inherently mistrusts agriculture and farming. In another essay, entitled, “Freeganism: Liberating Our Consumption, Liberating Our Lives,” Weissman attacks farming: “From the outset, the creation of farmland involves the complete destruction of preexisting habitat and ecosystems, whether this means logging a forest or simply threshing preexisting browse and to clear land for crop rows and loosen soil, inevitably leading to significant topsoil loss. Animal species and the ecosystems they are part of rely on a highly specific and delicate set of habitat conditions to survive. When we turn biodiverse, unspoiled plains and forests into farmlands, we kill countless animals that fall to their deaths as trees crash to the ground or who are crushed or to ground to their deaths by tractors or plows.”

In this essay, Weissman makes no distinction between ecologically sound methods of agriculture, and factory-farm, corporate monoculture which utilizes pesticides and other harmful petrochemicals that endanger humans, wildlife, water supplies and the health of our soil. It is obvious to me that he is either willfully ignorant of the differences between sustainable farming and corporate monoculture, or he simply does not care about them, because if he actually supported the local economy by buying organic produce from a reputable farmer who practiced sustainable agriculture, he wouldn’t be able to keep getting by on a free ride by dumpster-diving.

Oh, and stealing. Let’s not forget the stealing part.

What does he suggest as an alternative to farming? Well, he doesn’t actually suggest that farming cease–or if he does, he gives no viable alternative to agriculture as the basic means of food creation. He does, of course, as I noted in my earlier essay, invoke the glorious days of our hunter-gatherer past, when humans never saw the earth as raw materials for exploitation, and we only took what we needed and all was loving kindness and beautiful. And, of course, he equates freegans with the noble hunter-gatherers of old.

But I have a question.

If it is true that the goal of freeganism is to bring down capitalism and to create a new and different society that is not based upon the oppression of anyone or anything, then how exactly does a bunch of priviledged kids dumpster-diving for food accomplish this? What is the mechanism here? Sure, some folks leave the corporate-driven consumption cycle, but how does this stop factory farming? How does this create a new economy?

How, exactly, does ragging on vegans, many of whom support local food economies by carefully shopping at farmer’s markets, bakeries and tofu-makers, “stick it” to Pepsi-co?

It doesn’t.

Freegan philosophy is empty. For all of its high-minded ideals and long-winded arguments, it is simply a means by which people who feel powerless in the face of corporate hegenomy can feel like they are doing something worthwhile that will really bring about an end to the evils of capitalism. It is a way of getting something for nothing, while feeling heroic at the same time.

If I were a vegan, I’d be really pissed right about now.

As it is, I’m not a vegan, yet I am still plenty disgusted.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.