Noodle Shop Secret for Springy Noodles: Pre-Steaming

If you have ever eaten good wheat-based soup noodles or pan-fried noodles at a Chinese restaurant or noodle shop, one thing that you cannot help but notice is the texture of them. In soup, they are always springy, flavorful and firm, never mushy or overcooked, and when they are pan fried, they are toothsome on the inside, crispy on the outside and absolutely delicious. If soft fried for lo-mein, they always have a bite to them without being undercooked, and are resilient without being crunchy.

There is a secret to making good fresh (store-bought or homemade) Chinese wheat noodles better, and it is simple–so simple anyone can do it.

All you need is a bamboo steamer, a pot of boiling water and about ten to fifteen minutes of time, and you can pre-steam your noodles so that their fresh flavor is enhanced and preserved, and so that they are impossible to overcook into pallid mushiness. If you want, you can take fresh noodles, steam them, and then after they are cooled, you can pack them into plastic bags for your freezer or refrigerator. In the freezer, they will keep for two months, while in the fridge, they will keep for two weeks–much longer than they would otherwise. Or, if the weather is dry, you can allow the steamed noodles to dry completely to the touch in the air, and then pack them into airtight plastic bags to be used within three to four months.

To use pre-steamed noodles, you just cook them as you would normally–but be aware that to boil steamed noodles, either dried, thawed frozen or refrigerated–that they take a little longer to cook than they would if they were pre-steamed. They will cook in about three to four minutes, using my method for boiling noodles outlined here.

After they are boiled, they can drained and used in lo mein, topped with sauces, or made into a cold noodle dish, just as if they were plain boiled noodles. The difference being, however, a superior texture and flavor, all managed with just a few extra minutes of cooking time–which can be done hours, days, weeks or months ahead of time.

Method:

For one pound of fresh homemade or store-bought Chinese noodles (plain or egg noodles–it doesn’t matter which), bring water in a wok or a large pot to the boil. Divide your noodles into two portions, and spread each into a round nest in the bottom of a bamboo steaming basket. (If you don’t have a bamboo steamer, you can improvise by using a plate, a pot with a lid and an empty food can with the bottom and top cut off–you put about an inch and a half of water in the pot, put the can in the center standing up on its end, arrange the noodles on the plate and set it on the can. You need to make sure the can is shorter than the pot by at least one inch. Then, when the water boils, you put the lid on the pot and steam as directed.)

Fluff the noodles and loosen them as shown in the photo above as you arrange them, but make certain that the nests are not any taller than one inch. After they are arranged, bring the water in the pot or wok to boil, and set the two steamers, stacked on top of each other with the lid on the top basket, on top of the boiling water–make certain that the water doesn’t touch the bottom of the basket, and steam.

For homemade noodles, steam for ten minutes. For store-bought, steam for fifteen minutes. When they are done, they will be slightly darker in color, and shiny, and they will have a dense, springy texture. After you take the baskets off the pot, open them up, and remove the noodles, fluffing them with your fingers. Arrange each portion into a circular nest on a plate to cool and dry–be careful, because the noodles are quite hot when they first come out. (My fingers could take the heat, but if yours cannot, use chopsticks or tongs to remove them to the plates.) You don’t want them to cool in the baskets because they will stick together.

After they are dry and cool, each nest can be packed away in plastic bags and frozen or refrigerated, or they can be set on the counter to dry thoroughly, then packed in an airtight bag in a cool dry place.

Or, they can be used in any noodle recipe immediately.

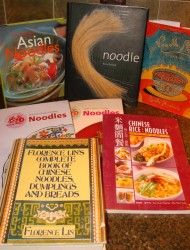

Chinese Noodle Cookbooks: A Handful of the Best Titles

There have been a strong handful of cookbooks written on the subject of Chinese and Asian noodles over the years; unfortunately, the best of them are out of print. But, luckily, they are reasonably easily found through Amazon as used books, or, if you have issues with Amazon, you can always try Bookfinder or ebay. (However, check prices on both Amazon and Bookfinder first–most of the time, the book prices on ebay are inflated. Now and again, I was able to find a bargain, but not very often.)

Of course, the best of the lot of these books is certainly the most sought-after title in the bunch and is certain to be the most expensive. However, I would say that it is worth every penny.

Florence Lin’s Complete Book of Chinese Noodles, Dumplings and Breads by the consummate Chinese cooking teacher and cookbook author, Florence Lin, is well worth the thirty-five dollars or more it is getting in the used book market these days. Why? Because not only does Lin devote her entire text to the myriad products of rice or wheat flour doughs in her book, she explains her methods clearly, thoroughly and in a voice that builds a cook’s confidence.

Lin explicates the minutia of cooking all sorts of Chinese noodles, giving all of the little tricks and tips that Chinese cooks have used for centuries to obtain different textural effects with these noodles. She gives historical background on the types of noodles as well as the cooking techniques involved in them, and for intensive recipes like fresh noodles, she gives step-by-step instructions which are written in a no-nonsense, erudite, yet refreshingly simple manner.

The one deficiency in this book is the lack of photographs illustrating the various noodle dishes. I find that when Americans are tackling unfamiliar recipes from other cultures, they are more often enticed into cooking new foods by delicious-looking photographs than they are by delectable descriptive prose.

The deficiency of Lin’s book is corrected by the Wei Chuan publications, Noodles: Classical Chinese Cooking and Noodles: Chinese Home Cooking, both buy Lee-Hwa Lin. Like all of the Wei Chuan bilingual Chinese/English cookbooks, these volumes are highly illustrated with clear, appetizing photographs that show each step of difficult recipes as well as lovely photos of the finished dishes. Of the two of these books, I have found the first, Noodles: Classical Chinese Cooking

, to be the most helpful, with recipes for dishes I have eaten in restaurants across the country.

There are drawbacks, of course, to both books. One, they are both now out of print, though still available in the used market. Two, I find that the recipes are skewed toward Taiwanese tastes (which makes sense, since the books are the publications of a famous cooking school in Taiwan), and so they often require a bit of work on my part to adjust them to make the flavors come out as I tasted them elsewhere. Finally, three–the format in which the recipes are written can be confusing the first few times they are read, at least until the reader gets used to them. They directions are clear, but abbreviated, and that can lead to confusion, which is not helpful to a new cook, especially one who is unfamiliar with Chinese foods.

Wei Chuan has come out with a new volume of Chinese noodle recipes: Chinese Rice and Noodles: With Appetizers, Soups and Sweets, by Su-Huei Huang and Su-Huei Huang. However, unlike the previous books in their series, this volume is not exclusively about noodles, and so the scope of the book is not nearly as interesting to a cook who wants to learn noodle cookery. That is the biggest drawback of the book–as always, it is lavishly illustrated with gorgeous photography, which nearly makes up for the lack of exclusive content on the subject of noodles.

Jacki Passmore’s The Noodle Shop Cookbook is a good companion to Florence Lin’s book. Although Passmore’s book is more of a survey of general Asian noodle recipes, she leans heavily upon Chinese recipes, gleaned from the favored street foods and noodle stall dishes beloved across every region. The recipes here are generally simple, easy to follow and give an excellent authentic flavor, although, like Lin’s book, there is a lack of photographs to entice a cook new to the subject of Chinese noodles.

Asian Noodles by Nina Simonds, like Passmore’s book is a generalized look at noodle recipes from all over Asia. However, Simonds’ book is highly illustrated with great photographs of both processes and finished dishes, and her explication of technique, ingredients and history is impeccable as always. There are more than Chinese recipes featured in this book, but China’s noodle traditions are well-represented and the recipes are all vibrant and flavorful.

Finally, there is the large-format Noodle by Terry Durack. An absolutely gorgeous book, filled with artistic photographs by Geoff Lung, Noodle is a visually appealing survey of the myriad forms noodles take across Asia. The recipes are all illustrated with artfully posed photographs, but there are fewer recipes than there could be. Chinese recipes are present, but are overshadowed by the many other recipes from the rest of Asia.

However, the book is visually inspiring, and is well worth looking at if you can find it in a library or a used bookstore.

These are the noodle cookbooks I have in my collection; there are a very few others available. In addition, there are many great noodle recipes to be found in general Chinese and Asian cookbooks by a great many authors. Some of my favorite noodle recipes, in fact, can be found in the books of Fuchsia Dunlop and Grace Young–both excellent cookbook authors whose explications of the culinary arts of China are invaluable to cooks everywhere.

Weaning Kids From Junk Food: Start Before They’re Born

A study recently published in the British Journal of Nutrition infers that mothers who eat a great deal of junk food during pregnancy and lactation, may predispose their children to prefer junk food to healthy food when they are weaned.

As reported by CBS News, the results of the study, conducted on rats, suggest that a heightened taste for junk food may be influenced in utero and while breastfeeding from a mother who eats a diet rich in fat, sugar and empty calories.

The researchers who conducted the study, Stephanie Bayol, Ph.D., and professor Neil Stickland, Ph.D., of London’s Royal Veterinary College found that when mother rats were fed junk food diets which included biscuits, marshmallows, cheese, jam, doughnuts, chocolate chip muffins, pancakes, potato chips, caramel and chocolate, their offspring, when weaned preferred these foods to regular rat chow.

Of course, the control group of baby rats whose mothers had been fed a diet of nothing bat rat chow also preferred the junk food diet (who wouldn’t–what the heck is rat chow, anyway–tasteless processed nuggets of crap?), but apparently, the junk food babies preferred to the point that they showed an exaggerated taste for it.

This exaggerated taste for junk food led to the study group of baby rats gaining more weight and showing a market lack of interest in the healthier rat chow.

The doctors concluded that it was even more important than ever for pregnant and lactating women to eat as healthily as possible and to not use the excuse that they are “eating for two” to gorge on unhealthy foods.

What do I think about all of this?

Well, in my experience, (and according to some other studies on the subject) infant food preferences are in some part shaped by their mother’s diets during pregnancy and lactation. This does make sense–because as mothers and doctors have known for generations, flavors from her diet come through the breastmilk, so it is only logical that a child will have a preference for tastes which they have experienced before.

Kat is a great example of this: while I was pregnant with her, I ate a great deal of spicy, garlicky foods, including curries and a lot of vegetable and tofu stir-fries seasoned with chilies, onions and ginger. What does she love to eat now? Lots of vegetables, curries, chilies and onions–she will eat pieces of caramelized onions gleefully, and will munch down on chili-seasoned anything with great gusto.

Of course, the fact is she wants to eat anything she sees me eat–which is exactly what Morganna did at this age (nearly one year old). One cannot discount the importance of the parents’ modeling of any sort of behavior, including dietary choice, when it comes to children. Kids do what they see their parents do, and that extends perfectly into eating as well. In this sense, human kids may be a good bit different than rat babies–so much of human behavior is learned, whereas much of rodent behavior is inborn, instinctive traits.

Even if a taste for fattening food can be influenced via the mother’s diet during pregnancy and lactation, her modeled behavior vis a vis food will have a strong effect as well, and should not be discounted.

In addition, one must remember, that all mammals (including rats and humans) have an inborn preference for sweet and fatty foods because in the natural environment, they are rare and valuable sources of calories. Of course, the modern world of cheap and plentiful food is not the environment in which either humans or rats evolved, so now we have the issue of our own biology being a liability.

In other words, I am not certain that this study means much of anything, really. There are too many variables involved, including the fact that what is true of rats is not necessarily going to be fully true of humans.

I would be interested in the results of a human version of this study, however.

Homemade Hunan Salted Chilies

Back when Fuchsia Dunlop’s Hunan cookbook, Revolutionary Chinese Cookbook came out, I wanted to make a jar of salted chilies as per her directions so that I could use them to get an authentic Hunanese flavor in my recipes. This condiment, which is easily made at home (a good thing, because it isn’t available in the marketplace) is nothing more than ripe red hot chilies, chopped up and tossed with salt, then sealed up and kept at cool room temperature for two weeks.

She described them as tangy, salty and hot, and said that they added amazing color and flavor to Hunan foods. Obviously, they are the product of lactic acid fermentation just like kimchi and saurkraut.

Since I love kimchi and I love chilies, I couldn’t help but want to make this.

Alas, I had to wait until now to do so because my ability to get a full pound of red, ripe chilies until now has been lacking. But, another benefit of late summer heat and sun is this: there are ripe chilies available at the farmer’s market in copious amounts. I picked up a pound of red cayennes–and boy are they HOT!

I know this because as I was chopping them, the back of my throat started to tickle. (I wore gloves, of course, but I didn’t wear a surgical mask. Maybe I should have had a gas mask, too?) Then, my nose started to run, my eyes watered and my throat began to actively hurt. All from the smell coming up off the chilies.

My throat bothered me the rest of the night into the next morning, long after I had tossed the chilies with the kosher salt and sealed them up tightly in a jar.

I can’t wait to try them in a recipe–I have one all lined up–chicken stir fried with rice noodles.

But, alas, I need to wait another week and a half. Right now, the salt has all dissolved into the juices which have come out of the chopped chilies, and the color of them has begun to deepen somewhat. The process is pretty fun to watch. I check on them every time I open up the pantry.

We’ll know how they turned out when I cook with them the first time. I just think it would be best for me to remember to turn the vent hood over the stove before I start stir frying lest I kill all the cats with chili fumes.

If you are brave or crazy enough to want to make a jar of these for yourself, here is Dunlop’s recipe.

Hunan Salted Chilies

Ingredients:

1 pound red hot chilies

1/4 cup kosher salt

Method:

Wash chilies thoroughly and discard any that show signs of mold or decay. Dry them thoroughly on a kitchen towel or a pile of paper towels.

Sterilize a jar and lid with boiling water or by running it through your dishwasher with a heat dry cycle. Make certain it dries thoroughly either in the air or through the dishwasher dry cycle. Do not use a paper towel or cloth to dry it directly.

Discard the stems of the chilies and chop them roughly. Do not remove the seeds. Place the chopped chilies into the jar with three tablespoons of the salt and with a sterilized chopstick or fork, stir thoroughly to combine the salt evenly among the chile bits.

When the salt is mixed in, level the top of the chilies, and sprinkle the rest of the salt over them, then tightly cap the jar with the lid and store, unopened, in a cool dark place for two weeks.

After that, it is ready to use. After opening, keep in the fridge, where it will keep for months.

Cold Sesame-Peanut Noodles Beat The Summer Heat

I always tend to lose weight during the months of August and September.

That is because those tend to be the hottest months of the year here in Southeastern Ohio. Humidity is usually off the scale, and no breezes blow, while the endless sunlight pours from an azure sky in unremitting waves of heat, crashing down over every living thing mercilessly.

If it weren’t for fresh tomatoes, green beans, chilies, corn, peaches, eggplant, garlic, basil, cucumbers and bitter melons, I would absolutely abhor late summer and would immigrate to Siberia just so I can enjoy the balmy weather.

But, the fresh produce wins out over my inborn dislike of intense heat every year and I make it through the hottest days of summer by eating very little except salads, fruits, and anything that is cold –most especially cold noodles.

I adore Chinese cold noodles–I first started making them when we lived in Athens about twelve years ago. For a while, there was a tiny Chinese restaurant located in a most disreputable looking storefront with only a few tables scattered about the decrepit looking linoleum floor. There was no decor to speak of, but they made a dish they called “Hunan Cold Spicy Noodles” that were to die for. They were absolutely and utterly refreshing during the dog days of summer when I barely went near the kitchen to cook, much less to eat. Fiery with chilies, and sprinkled with icy cucumber shreds, these noodles were a godsend, and they opened my eyes to the possibilities of Chinese noodles served cold.

Later, when we moved to Maryland, I became acquainted with Cold Sesame Noodles–a dish of chewy fresh egg or plain noodles dressed with Chinese toasted sesame paste, garlic, sugar, vinegar and soy sauce and garnished with bean sprouts and cucumbers. Chinese toasted sesame paste is similar to Middle Eastern tahini–except that the seeds are toasted dark before being ground up. If it turns out you cannot get the Chinese kind, just use tahini instead, and add an extra teaspoon of toasted sesame oil to the dressing mixture to make up for the tahini’s lighter flavor.

The creamy sauce was slithery and satisfying without being rich, and the noodles were both tender and chewy and were substantial enough to quell hunger without being so heavy as to weight the stomach down. They were amazing, and quickly became Zak’s favorite summer food, which he could eat seven times a week if I’d let him.

I learned as I researched the sesame noodles so I could recreate them for Zak when we moved back to Ohio, that many restaurants use peanut butter in addition or instead of the sesame paste. This originally came about because sesame seed paste was at one time difficult to find in the US, so enterprising Chinese chefs replaced it with the easily obtained peanut butter. But later, some chefs kept using it in addition to the sesame seed paste because they and their customers liked the blended flavor better than the traditional dish.

I cannot argue with them on that point. I like the traditional dish well enough, but I was never as much of a fan of it as Zak was. But, man, if you put peanut butter in my cold sesame noodles or get cold sesame noodles in my peanut butter, I get all into it. Add to the dish the musky fire of Sichuan broad bean chili paste and Sichuan peppercorns, and sprinkle it all with some slivered carrots and cilantro, and suddenly, my jaded summer tastebuds are having a party in my mouth, one to which my appetite is invited. Wow! It makes me want to eat again, which is a good thing.

A cook who doesn’t want to eat is a very sad creature to behold, let me tell you.

Another cool thing about this dish is that it can be made totally vegan by exchanging vegetable stock for the chicken stock and it makes a great little supper for four hungry vegetarians or two, if they are really hungry.

One word of advice, however–only make as many as you are going to eat that day. These noodles don’t really keep very well in the fridge, unlike the Hunan Spicy Noodles recipe I have already posted. The dressing for this one starts to seize up and get sticky and unappetizing if you leave it in the fridge for more than an hour or so. It is just one of those recipes that is best made fresh.

Also–while I specify making this dish with fresh plain or egg noodles that are square in cross-section, and are about 1/8″ wide, you can use 1/4″ wide dried noodles for it instead. The texture is different; with dried noodles, you lose the substantial chew of the fresh noodles which goes a long way toward feeling full without becoming stuffed. But, if you need a lighter dish, one that is still soul-stirring, then try the recipe with the dried noodles and see how you like it. (The photograph below of the noodles in the red bowl, has the recipe made with dried plain wheat noodles. The photograph at the beginning of the post has the recipe made with fresh plain noodles.)

While you can make the sauce in a blender or a food processor, I find that using an immersion blender is the easiest way to get everything, particularly the stiff and thick sesame paste, blended. Sesame paste is spoon-bendingly stiff, and it takes some hefty forearm muscles and a stubborn will to get it out of the jar, but once you taste the finished noodles it is all worth it. An immersion blender manages to not only blend together the peanut butter and sesame paste, but also minces the cilantro, garlic and scallions into very fine bits, which makes the flavor of the sauce positively radiant, while making cleanup easy. (I hate washing regular blender jars–I just want to say that. Immersion blenders are so much easier to clean!)

My last tip has to do with the noodles. After they have been rinsed and soaked in cold water to chill and firm them, and you are about to combine them with the dressing, shake excess water off, but don’t blot them or drain them in a colander overmuch. You want them to be slightly damp, because the extra drops of water help the sauce mix into and cling to the noodles.

I can’t guarantee that these noodles will entice every sun-weary foodie to eat, but I suspect that quite a few of them might have their waning summer appetites perked up by a bowl of these fragrant, spicy, creamy delights.

I know it works on me, anyway.

Ingredients:

1 pound fresh or dried medium-wide plain wheat Chinese noodles

1/2 cup carrots, peeled and cut julienne

1/2 cup cucumbers, peeled, seeded and cut julienne

1/2 cup roughly chopped cilantro

1/2 cup thinly sliced scallion tops

For the Sauce:

2 heaping tablespoons toasted sesame paste

2 heaping tablespoons smooth peanut butter (all natural or Simply Jif)

2 tablespoons minced scallion, white part only

2 1/2 tablespoons finely minced fresh garlic

1 tablespoon finely minced cilantro leaves

2 tablespoons chicken or vegetable stock/broth

2 tablespoons light or thin soy sauce

2 tablespoons rice vinegar

1 tablespoon Shao Hsing wine or dry sherry

3 teaspoons chili-broad bean sauce/paste (or to taste)

1/4 teaspoon toasted and ground Sichuan peppercorns (or black pepper to taste)

1 teaspoon sesame oil

2-3 teaspoons honey or raw sugar (this is to your taste–I like it less sweet, Zak likes it sweeter…you try it with less first, taste it and then mix in some more if you want.)

Method:

Boil the noodles according to the directions in this post. Keep the noodles chilled in cold water until you are ready to dress them with the sauce.

Blend the sauce ingredients together using an immersion blender, a blender or a food processor until it is combined smoothly into a dark reddish brown sauce.

Drain the noodles, shaking them in a colander until they are mostly dry, but still with some droplets of water clinging to them. Pour one half of the sauce into a large bowl, put the drained noodles on top of them, and pour the rest of the sauce over them.

Toss the noodles with either two sets of chopsticks, two forks, or clean hands until the sauce coats every strand of noodles. Divide into serving bowls (it serves four for a light meal, six to eight for a cold appetizer) and sprinkle the vegetables, cilantro leaves and scallion tops over them as a garnish.

Serve immediately–do not refrigerate. If you wish to make this ahead, you can make the sauce ahead a few hours ahead and chill it, then bring it to room temperature to serve. You can make the noodles about an hour ahead and soak them in cold water until service.

Note: You can add less chili flavor if you want, but if you want more, you can always garnish with thinly sliced red chilies. Bean sprouts are good as a garnish, as are sweet red peppers cut julienne. Snow peas, thinly sliced on the diagonal are also good as are raw sweet purple onions. And, if you like, you can use all sesame paste in this recipe, which would be traditional, but I like the peanut butter blended in better, myself. However, all peanut butter doesn’t taste as good, at least not to me.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.