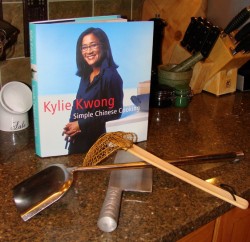

Book Review: Simple Chinese Cooking

Kylie Kwong is a successful Australasian restaurateur, chef, television personality and cookbook author whose aim is to demystify Chinese cookery and make it accessible to the average home cook.

While her new book Simple Chinese Cooking is a really good step in that direction, there is too little emphasis on technique to truly explicate even a simplified version of Chinese cuisine. Each recipe is lushly illustrated in true food-porn style with sexy closeups of perfectly wok-seared meats and produce all garnished with precisely cut slivers of chile or scallions. However, there are precious few photographs showing how to shred vegetables or slice meat evenly in order to get such gorgeous results. Nor is there much description of how to do it in clear, precise prose.

Instead, the oversized book is laid out more like a coffee-table art book; in fact, the sheer size of it (approximately 9.5″X10.5″) makes it awkward to use in the kitchen. Which is a shame, because the minimalist recipes are very useful and quite scrummy.

Each recipe takes up one full page, however, there is scant instruction on method, so there is much white space. Opposite each recipe lays the finished dish, simply presented on plain white plates, but gussied up with colorful fringes of aromatics so precisely cut they look like feathers or blades of grass. It is all quite artistic, but I am sure it will look less so after soy sauce is dribbled all over that pristine white space and notes are scribbled in the margins.

But what about those scrummy recipes, you ask? Are they good? Are they simple? Can I make them?

Yes to all of those questions. I have cooked from the book, and the recipes are not just workable and simple, they give excellent results.

Kwong’s recipes are minimalist to the point that at first I wondered how well they would taste. However, Kwong’s Cantonese family taught her well the art of taking the freshest possible ingredients and with precise preparation, the application of high heat and a gentle hand with the seasonings, and turning them into dishes that emphasize the natural goodness of food. The first recipe I tried didn’t even use soy sauce; instead, only Shao Hsing wine, salt, garlic and scallions seasoned the dish. The results were delicious. When I cooked it a second time, adding my own subtle touches (a tiny pinch of raw sugar and a drizzle of sesame oil), the results were similarly fantastic.

Following Kwong’s recipes is a lesson in keeping a light touch and learning to appreciate the inherent beauty in food.

Because of her minimalist approach, Kwong emphasizes the use of the best possible ingredients. She instructs the cook to use organic eggs and free-range, organic meats and organic vegetables and fruits whenever possible, noting that the difference in flavor is well worth the extra expense. (She also uses only tenderloin in her beef recipes, suggesting that it is the only truly good cut for stir-frying. This extravagance–which is fine for upscale restaurant cooking–strikes me as odd in a book that is meant to make Chinese food accessible to home cooks.) In addition, Kwong notes that seasonal foods are to be preferred and that these foods all are more ecologically viable as well.

I wish that Kwong had spent more time instructing the newcomer on how to successfully stir fry in a wok on a home stove, and how to cut meats and vegetables with the precision necessary for successful stir frying, she did an admirable job in presenting really interesting recipes with a minimum of ingredients, most of which are available at typical American supermarkets. While I was disappointed that some of her vegetable recipes were repetitive (you really don’t need separate recipes for bok choy with oyster sauce, choy sum with oyster sauce and gai lan with oyster sauce–they could have been presented as variations of each other on one page, with the other two pages devoted to different recipes), Kwong made up for it by presenting interesting variations on Chinese-style soft-boiled eggs. In fact, she presents quite a few egg recipes, all of which looked and sounded amazingly good and are nothing like what is found in most Chinese cookbooks.

In short, I think that this cookbook, while it suffers from a few significant shortcomings, does succeed at showing home cooks unfamiliar with Chinese cookery that it doesn’t have to be difficult, time consuming or require a whole new pantry full of unfamiliar foods. I’d like to see more from Kwong, especially if she could manage to combine more in-depth lessons on technique while presenting more recipes that are simple, yet amazingly delicious.

Staple Ingredients of the Chinese Pantry

A couple of days ago, Aileen from Canada wrote to ask me what my favorite brands of some staple Chinese pantry items were.

I thought that was a fair question, and is one I have been asked often, so I figured it was high time I got around to actually writing a post listing what I thought the most necessary basic Chinese pantry items were, what to look for in them, and where to buy them. So, I dug around in my over-stuffed pantry closet and narrowed all the goodies down to fourteen simple basics, many, if not all of which are available at most large American supermarkets. With the items in this list, augmented by general pantry staples such as sugar, salt, cornstarch, peanuts, chicken broth, long grain rice, peanut or canola oil, and black pepper, one can take most fresh ingredients such as tofu, meats and vegetables, and create a plethora of dishes from every province of China. (Look for another post sometime soon on a few optional items which will extend the range of dishes that can be created if they are added to this basic Chinese pantry.)

As I said, many of the items on this list can be found increasingly in American grocery stores. You may not be able to find the specific brands that I prefer, but if you lack access to a local Asian market or prefer not to shop in one, and do not wish to order these items online, then go with the brands you can get. For those items on the basics list which cannot be found in a typical American grocery store, I will list good substitutions. Please also refer to the photographs for product identification; some of these ingredients, such as the wine and the fermented black beans, have primarily Chinese characters on the labels, so the photographs will help you figure out if it is the brand I am talking about or not.

(Important: For those of you who are wheat and gluten sensitive–many of these items contain wheat. This includes soy sauce, so please, read labels! For wheat free soy sauce–use tamari soy sauce. My favorite tamari is San J brand which can be found in health food stores, regular supermarkets and some Asian grocery stores.)

Most of these items have a long shelf life; I will give storage tips and shelf-life information where it is applicable.

Finally, what should you do if you prefer a brand of an item which your Asian market does not carry? How do you get them to order and stock what you want without struggling too much with the language barrier?

There are two simple answers to this question. The first and easiest method is to save the package, bottle, jar or can of the product you prefer, cleaning it up so it doesn’t get sticky and smelly. Then you take the cleaned up container to your friendly neighborhood Asian market where you shop and hand it to the owner while asking, “Can you order this?”

The other method involves finding a picture of the product online. Print out the photo and bring it with you to the shop, show them the picture and ask if they can order it.

If neither of those gambits work, at the end of this post I will give several tried and true online grocers you can order from.

The Basics

Light Soy Sauce: This is not “lite” soy sauce as in low-sodium soy sauce; this is your standard, basic soy sauce, which is sometimes also called on the bottles and in cookbooks, “thin” soy sauce. (For an extended discussion of the different types of soy sauce and their uses, see my post A Soy Sauce Primer.) The brands of light soy sauce I prefer are Kimlan Premium Aged and Pearl River Bridge, in that order. The thing to look for in any soy sauce you buy is that it is naturally brewed, and while I would prefer that everyone use Chinese soy sauces in Chinese cooking, if all you can get is Kikkoman’s naturally brewed at your grocery store, by all means, use that. Soy sauce keeps nearly forever and does not need to be refrigerated, though I know of quite a few people who don’t use it often who do refrigerate it.

Dark Soy Sauce: This soy sauce is basically thin soy sauce to which caramel or molasses has been added, giving it a slightly sweeter flavor, a thicker texture and a darker, more reddish color. This is the soy sauce that is used to give red-cooked (braised) dishes their lovely color, and it is widely used in beef stir fries. In cooking beef, the sweeter flavor gives a good fragrance and flavor balance to the strong taste of beef, and it gives a very good dark color to the cooked meat. Again, my favored brands are Kimlan and Pearl River Bridge. Again, look for naturally brewed dark soy sauce, and if you cannot get it at your local grocery store, I suppose one could use thin soy sauce with a small amount of Kitchen Bouquet to simulate dark soy sauce, but as I have never tried that trick, I don’t know whether the flavor would suffer as a result.

Rice Wine: I prefer Shao Hsing wine, which is not a brand, but a type of Chinese rice wine. It is amber-colored and very nutty with a slightly sweet aftertaste. The brand I prefer is unsalted–it is drinking quality, not “cooking wine”–and it comes with either a red or gold label with Chinese characters on it. The fine print in English identifies it as being made by the Zhejiang Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs Company, Shaoxing Wine division. It is not very easy to find, so if you cannot get it, the best substitute that most Chinese cookbooks stipulate is a good quality dry sherry. I concur–in cooking both Chinese and European foods, I have used the two wines interchangeably with no noticeable difference. However, I have to admit that if I am sipping, I prefer Shao Hsing–the nutty flavor is just lovely and it has a distinct warming quality that for me sherry lacks. Shao Hsing does not require refrigeration and lasts forever.

Rice Vinegar: Rice vinegar has a softer flavor than either cider vinegar or distilled white vinegar. It is used both in Chinese cooking and in making uncooked sauces, dressings and dips. Be careful if you use a Japanese rice vinegar that it is unseasoned–many Japanese brands in American grocery stores are pre-seasoned for use in sushi, so they have added sugar, which would mess up the flavor balance of your dish if the vinegar is only meant to be sour, not sour and sweet. If you cannot find any rice vinegar, Australian-based Chinese chef, Kylie Kwong uses malt vinegar as a substitute. I haven’t tried it myself, but I suspect it would be very good. The brand of rice vinegar I use is Kong Yen Genuine Brewed brand with the yellow and green label. Vinegar does not require refrigeration and lasts forever.

Oyster Sauce: Oyster sauce is made from oyster extract, sugar, starch, salt and water. What you want to look for is a brand where oyster extract or oysters are the first ingredient listed. If sugar, MSG or salt is the first ingredient, put the bottle down and step slowly away. It will taste harsh and icky and will make your food taste harsh and icky. My favorite brand used to be Lee Kum Kee Premium Oyster Sauce until I found Amoy Oyster Sauce with Dried Scallop. Wow! That stuff is rich, delicious and fragrant and has kicked my Cantonese recipes up several notches. If you can find it, grab it up and try it out. I always keep oyster sauce refrigerated, and I suggest you do the same. Since the sauce is so thick, it helps to take it out a couple of hours before cooking to warm it up so you can get it out of the bottle. Alternately, you can screw the cap on tightly and store it upside down in the fridge so you can always get the sauce to come out even if it is cold.

Hoisin Sauce: Hoisin sauce is a dark, thick jam-like condiment that is made from fermented soy beans, wheat, sugar, garlic and vinegar. This salty-sweet-tangy sauce is used both at the table and in cookery. Although I have seen it kept on the table unrefrigerated in some Chinese and Vietnamese restaurants, I always refrigerate mine. The brand I use comes from Koon Chun Sauce Company–it has a yellow, blue, white and red label that is fairly low key.One side of the label is written in English, and the other in Chinese, so if you can only find sauces with Chinese writing, turn them around, and you can read the other side. All of their sauces are good, though. Many American grocery stores also carry Lee Kum Kee brand, which has a more colorful label, and which is quite tasty, too.

Ground Bean Sauce or Bean Sauce: This is probably one of the most versatile ingredients in the basic Chinese pantry. (For an in depth discussion of Asian fermented soy pastes, see Soybean Pastes: A Primer.)The two medium brown fragrant products are the same, except ground bean sauce has been ground into a thick puree. Which one you choose to have around depends on whether you want your Chinese dishes to have chunky or smooth sauces. (I tend to keep the ground bean sauce around myself. And yes, I also prefer smooth peanut butter. Sans salmonella, thank you.) Made of soy beans, salt, wheat, and sugar, and unnamed spices, this sauce gives a burst of umami “oomph” to any dish with just the addition of a teaspoon or two. It is great with meat or tofu dishes. The brand I prefer is Koon Chun, but again, Lee Kum Kee’s is also good.

Fermented Black Beans: These little black, wrinkled salty wonders have become one of my favorite pantry items of all time, and I use a lot of them in my cooking. These are black soybeans which have been cooked, salted and fermented, often with slivers of ginger, and this treatment turns them into flavor powerhouses. They smell somewhat like a good aged cheese, and surprise! They are absolutely filled with natural glutamates. They make whatever they are stir fried, stewed, steamed or simmered with taste amazing. I cannot praise them highly enough. They are quite inexpensive and are easily found in Asian markets, packed either in cardboard cartons, jars or cellophane packets. I use one of the brands that comes packed in small cellophane packets–the front of which are labelled mostly in Chinese in gold, yellow and black. The packets are clear so you can see the beans, and in fine print on the back, you can read in English, “Kui Fat Food Company, Hong Kong.” The only substitute for these beauties that I can think of would be black bean and garlic sauce, which made by Lee Kum Kee, can be found in many American grocery stores. While they probably don’t need it, I store them in the refrigerator, and like most fermented products, they last for years.

Sesame Oil: When I say “sesame oil,” I am talking about the dark amber-colored, toasted sesame oil that is used in small amounts for seasoning, not the pale colored cold-pressed stuff that is used for cooking and salad dressings. Widely available both in the Asian sections of American grocery stores and Asian markets, toasted sesame oil is a necessity in the Chinese kitchen. Used at the end of stir frying or to dress steamed or braised dishes, a tiny amount of this very strong-flavored nutty oil will impart exceptional fragrance to any dish. It is also widely used in dipping sauces, cold noodle dishes and salad dressings, and is ubiquitous in many Asian cuisines. My favorite brand is Kadoya, which is Japanese, and is easily recognized because the bottle has a pinched-in “waist.” My advice is to buy the smallest bottle and keep it at room temperature in a dark, cool place. It will last for a good long time, but if it starts to smell rancid, obviously get rid of it. If you live in a very hot climate without air conditioning, go ahead and store it in the fridge, and just take it out a few hours before using it to warm it up to room temperature.

Chile Garlic Sauce: This tasty condiment is usually made of chilies, garlic, and salt, all ground together into a thick liquid. Some brands add a bit of vinegar or sugar to tweak the taste of this gloriously scarlet sauce, but most of them taste much the same. It is used to add tangy heat to cooked dishes, dipping sauces and dressings. The two brands I favor are Lee Kum Kee which is often found in American supermarkets, and Oriental Mascot, which is a bit less sweet and a bit hotter. I do store this one in the fridge, even though it likely isn’t necessary.

Dried Chilies: While my favorite dried Chinese chile peppers come from Penzey’s (Tien Tsin–these lovely little fellows are hot to trot), any dried 1-2 inch long deep red chilies you can get from the Asian market or the Asian section of your grocery store will do to make great Sichuan and Hunan favorites like Kung Pao Chicken. You can substitute red chile flakes from your grocery store, but only if they are very fresh. (They are not as versatile, in that you cannot keep the seeds out of them, as you can with whole chilies, but they also are not as hot as the Chinese or Thai chilies you get from the Asian market. I store my whole dried chilies and chile flakes in the freezer because I buy them in bulk. If you get them in smaller amounts, just keep them in an airtight container in a dark, cool cabinet. These will eventually lose potency after a year or six months, however, no matter how carefully you store them, so buy only as much as you think you will use quickly.

Dried Black Mushrooms: Also known as Chinese black mushrooms, these are nothing more than dried shiitake mushrooms. Commonly found in all Asian markets, and available in some American supermarkets, these dark brown mushrooms may not look like much, but they pack a powerhouse of flavor and texture in a small, often wizened, package. I don’t use any particular brand of them; I just look for the nicest variety I can afford. In general, what you want are plump, dark brown caps with lots of paler crackles on them such that they resemble flowers. Thinner, darker caps often have little flavor and seldom rehydrate well. One could substitute fresh shiitake mushrooms, but at a significant flavor and texture loss. When you soak the dried mushrooms in warm water, chicken broth or wine, you end up releasing the natural glutamates present in the mushroom. Then, after that soaking liquid is filtered, it can be used to add flavor to whatever you are steaming, stir-frying, simmering or braising. Also, dried mushrooms have more flavor and a chewier texture because when they are rehydrated, you never get all of the original volume of water back into the tissues, so the flavor is concentrated when compared to a fresh mushroom. I have successfully dried fresh shiitake mushrooms just by leaving them out in a dry dark place in the winter in my house, if you want to give that a try. Storage for these is simple–keep them in an airtight container somewhere cool and dark, and they last for a very long time.

Dried Rice Noodles: I am seeing these dried “rice sticks” as they are sometimes called, appearing in more and more mainstream American supermarkets, and that is all to the good. They are good in soups, or soaked and then stir fried for chow fun, though, in truth, fresh rice noodles are better for the latter dish. (Better, but much harder to find, alas.) These are inexpensive, they keep forever and a day, and they come in all sorts of sizes. I find the quarter to half inch width the most useful, but I keep a variety on hand for whenever I feel like making a cheap, tasty meal. You soak these in warm water then drain before stir frying them, or simply boil them before adding them to your soup. I have found no particular brand to be better than any other, either, so buy what you can find.

Dried or Fresh Wheat Noodles: This is a very broad category, for the Chinese love their noodles. Wheat noodles can come with or without egg, and they can come par cooked and dried, deep fried and dried, fresh and refrigerated and fresh, then frozen. I tend to keep non-egg dried wheat noodles in my pantry, as well as some fresh, frozen egg-containing lo mein noodles as well. For many applications, such as noodles in soup, or cold noodle dishes, one can substitute ramen (but leave off with the seasoning packets, and be aware that these noodles are deep fried and are thus not good for the waistline), or even Italian spaghetti. For stir fried noodles, I prefer fresh Chinese egg noodles. Some American grocery stores carry the fresh noodles in their refrigerated sections next to wonton wrappers, while other grocery stores carry dried Chinese wheat noodles in the Asian section. Look around and see what you can find. For dried noodles, I have no particular favorite, but I do like Twin Marquis brand fresh frozen lo mein noodles.

Finally, here are a couple of places online where you can order Chinese ingredients if you have no Asian market nearby and your grocery store has an inadequate Asian foods section.

The Oriental Pantry

Wok Wonderings

I get emails all the time about woks. Where to buy them, what to look for in them, and what to do with them once they come home.

Most of them have pretty standard, simple answers, but sometimes I get more complex questions which deserve to be answered publicly. In my experience, for every one reader who emails me a question, there are bound to be at least another four or five readers out there who have the same questions or experiences, but haven’t written because they are too shy to do so. Hence, I will write a post now and again outlining these questions and answers for everyone.

Remember, while I am very experienced in wokly matters, I am not the be all and end all authority on the subject; many of my answers will be a matter of opinion. I have my favorite ways to season woks, for example, but other folks, such as Grace Young, do it differently, and that is fine and dandy. Both ways work just fine and you will end up with a great patina in either case. Other answers, however, are pretty much a case of fact, and I strive to differentiate between the two.

What is the grey sticky stuff coating my new wok?

Enough preamble. First up, we have Andy, a friend of mine who lives in New York City. He and Lynne received a carbon-steel wok for Christmas which had no instructions on what to do with it. Neither of them know much about woks, except that one stir fries in them and one stir fries in them over high heat. Specifically, neither of them knew that a carbon steel wok must be seasoned before using.

So, out of the box the wok came, and into the kitchen it went. Excited to make something good for dinner, they cut up chicken and vegetables, and started cooking.

Over high heat, Andy noted that they smelled an odd odor, rather like a heating car engine or some sort of motor. When they threw the chicken in to cook, they noticed that while it was developing a nice brownish crust, it was streaked with ugly greyish bits that smelled metallic and dirty.

Luckily, they did not taste the chicken bits and threw them immediately away, because they were contaminated with the non-edible machine oil that coats carbon steel woks after they are made and before they are sold. This thick, viscous oil is used to keep the woks from rusting on their way from the factory to the store to the new owner’s kitchen.

Once a wok gets to the kitchen, this oil coating -must- be removed.

How?

With very hot water, dishwashing detergent, a scouring pad and elbow grease. Scrub the daylights out of any new carbon steel or unseasoned cast iron wok which comes into your possession. Scrub like your life depends on it. Scrub it once, rinse. Scrub it twice and rinse, and if it isn’t scrubbed down to bare metal, scrub it again for a third time.

Hopefully, this will be the very last time your wok will be scrubbed this vigorously.

To season it, heat the wok on high heat on your stove top. Pour about three tablespoons of peanut or canola oil into the wok, and using a long-handled spatula or set of tongs, push around a paper towel that has been folded into eighths all around the wok. When the oil is well spread, pick up the wok (with pot holders if you need to) and carefully tip it over the fire, allowing all parts of the outside of the wok to be heated by the flame. Turn the heat down to medium and keep moving the wok over it to keep it nice and warm, while rubbing the oil around with the paper towel now and again.

When this is done, remove the wok from the heat, let it cool down and wipe the excess oil away. Repeat the process once more.

Then, heat the wok empty over high heat until it begins to smoke. Add two tablespoons of peanut or canola oil and stir fry sliced ginger and scallions, scooping them and the flavored oil all over the wok with the wok shovel or by lifting the wok and swirling the oil around. When the ginger and scallions are quite brown, dump them out, let the wok cool and wipe the excess oil away.

After that, your wok is ready for cooking.

For another method of wok seasoning that is taught by Tane Chan, owner of The Wok Shop in San Francisco, check out Kirk’s detailed and illustrated post here.

Can an old wok get bad breath? If so, can it be saved?

Another question came from a vegetarian who had inherited an old wok that had been stored unused in a friend’s garage for years.

He said it smelled funny, like stale pork, and wanted to know if a wok could acquire “unwholesome wok hay,” and if that was the case, what could he do about it.

Unfortunately, the answer to his query is yes. A seasoned wok, left neglected in a dank place, can get a funky odor that will impart less than savory flavors to whatever foods are cooked in it. It sounds to me as if he has a wok that had been seasoned with lard once upon a time and was used often to cook meat, and the smell is not something a vegetarian would want in his food.

What to do about it? Well, unfortunately, when it comes to a case like this, it is best to scrub the patina out of the wok, bring it down to bare metal and start over by reseasoning it–this time with vegetable oil. Now, the good news is that this sort of treatment absolutely will not harm the wok in any way, and this young man will end up with a perfectly good wok for free, or rather the price of some elbow grease and patience.

How to scrub it out? Well, he can use the method outlined above for getting rid of the oil coating from a new wok, but he will have to work a good bit harder, since the seasoning is effectively baked in. He will likely be more successful by getting a really big box of salt, then dumping about a cup of it into his wok and heating it up on very high heat. Then, using a metal scouring pad and a long handled spatula or set of tongs, he needs to scrub at the wok. The heat allows the pores of the metal to open, and will release some of the oil and its scent, while the salt not only acts as an abrasive, it absorbs some of the oil and the odor.

Scrub the wok well, then cool it down, and rinse out the salt. Follow with a scrub with hot water and detergent.

Repeat as necessary until the wok is brought back to as close to a bare metal finish as possible.At this point, he can reseason his using whatever method he prefers.

Can a wok really never be too hot, or is that just a myth?

Elliott from Texas wrote to ask this question. I’m going to just quote his email here, with his permission, because he states the problem so eloquently:

“It seems like everything I read says that you can’t have the wok hot enough or there’s no such thing as a wok that’s too hot. Not wanting to smoke up the house by cooking on the stove, I purchased an outdoor propane burner designed specifically for woks, as well as a 14” carbon steel wok from China. I finally got everything set up yesterday and went out to “season” my brand new wok. This burner I have is capable of throwing 65,000 btu but, everything I’ve read says crank it up…so I

did. The seasoning method I used was what came on a little flyer withmy wok, namely, heat it up and put some oil (canola) in, swish it around and let it cook until the surface of the wok turns brown. Here’s where the puzzlement began. As soon as I dropped the oil into the wok, poof…..it ignited and sat there burning. I’m pretty sure that’s not what was supposed to happen…right? So my question is: did I get the wok too hot? Maybe I put in too much oil? After the fire went out, I was left with a charred clump of nastiness in the bottom so I went and scrubbed that out and started over with the heat set MUCH lower this time. That seemed to do better and I ended up with a nice brown patina all over the wok.I’ve not made a dish with it yet but am wondering….can I actually get the wok too hot?”

That saying, “You can’t get a wok too hot,” is not exactly a myth, but neither is it always true. In the case of most American home stoves, it is absolutely true. When someone is using an outdoor burner that pours out 65,000 BTUs of raw power, it is false.

As a rule of thumb, when your oil ignites upon contact with the wok, the wok might just be a little too warm to cook in.

That said, I was happy to find out that Elliott was cooking outside on a concrete and brick patio with a fire extinguisher and wok lid handy just in case something went awry. When you are working in high heat and high flame situations, safety considerations are quite important.

Most instructions on wok seasoning are not geared for anything other than traditional American gas or electric stoves which are lucky if they go up to 20,000 BTUs. These instructions certainly are not written for anything like what Elliott has on his patio, or for a professional wok stove which can throw out 300,000 BTUs. So when these instructions say high heat, they don’t mean that much high heat.

Elliott had enough sense to do the right thing, though I do want to point out it was in no way because he used too much oil. In fact, if he had used less oil on such high heat the effect might have been even more dramatic–it may have reached ignition temperature so fast it would seem to vaporize into an oily black smoke with only the slightest puff of flame visible. While that might look neat, it would not end up with a seasoned wok, and it could singe eyebrows.

What is my advice for cooking on an outdoor wok burner?

Scale back the heat a bit. While professional chefs in Chinese restaurants regularly crank their 300,000 BTU wok stoves up on high, they also are most often cooking with much larger woks and a lot more oil. This allows them to use higher heat, but even so–their woks do not last very long under this kind of stress. Woks used like this do not last spans of years–they last months. In order to avoid burning holes in your wok, ease up on the heat.

Also, it helps to ease up on the heat until you can stir fry fast enough to keep up with the heat! Having used a wok on a regular electric home stove, my 27,000 BTU AGA, and on a 300,000 BTU professional behemoth, I can tell you–you have to work very quickly and very precisely. I would not have been as successful with the professional stove if I had not been so experienced at stir frying on lower powered stoves and knew what I was doing. Learning to cook at such high heats is difficult.

Besides, even at lower BTUs, it is quite simple to make perfectly good stir-fry dishes, especially if you follow my techniques for better stir frying.

And one more nice thing–you are not quite as likely to set yourself or your food on fire at lower temperatures. Work your way up to the full power and then invite everyone over and show off!

One last question:

If a properly seasoned carbon steel or cast iron wok is naturally non-stick, why do you need a bamboo scrubber?

This one is an easy one.

When you use allow meats that have been marinated in cornstarch and sugar to caramelize on a hot wok, and then deglaze it, a thick, somewhat sticky sauce is created. When you scrape the finished dish out of the wok onto a serving platter, some bits get left behind. That sort of sauce is pretty sticky, and so now and again, they are stubborn and cannot be simply rinsed away with a strong spray of hot water. In cases like that, I use the traditional bamboo brush to gently scrub any sticky bits away.

The bamboo performs the job admirably on a hot wok without endangering my fingers or damaging the patina.

More on MSG and Glutamates

When I wrote the post on monosodium glutamate yesterday, I neglected to really explain what glutamates are.

Simply put, they are amino acids, which are the building blocks of protein. There are specific glutamate receptors on our tongue, which allow us to experience the taste which in Japan is called “umami.” This fifth taste is one of savory, meatiness, and is naturally occurring in glutamate rich foods such as seaweed, fermented soybean products, fermented vegetables, meat, shellfish and certain types of vinegar.

Nika, at Nika’s Culinaria, wrote an excellent well-researched post explaining the chemistry of MSG and the health implications for humans ingesting large quantities of it. In light of her findings, I am less sanguine about trying out a pinch or two of MSG in my own cooking, even if that means I never quite manage to replicate that dish of stir fried bean sprouts and shrimp that lives in a golden haze in my memory. I think I will stick with the natural sources of glutamates as I have always done.

Last year, I wrote a series of posts about umami that explained the chemistry, the uses and where to find natural ingredients that include a healthy dose of glutamates which readers new to the concept may find useful and interesting.

Here are the links:

For the introductory overview: Do You Know Umami?

All about soybean sources of glutamates: Got Umami? Soybean Ingredients of the East

Information on glutamate ingredients from the sea: Umami From the Oceans of Asia

Glutamates in vegetables: All the Greens that Grow–Umami in Vegetables

Glutamates in meats: Umami–The Meat of the Matter

Fermented and fungus-based glutamates: Umami–The Power of Fermentation and Fungus

Western glutamate ingredients: Umami in the West

What you will find in reading through these archived posts is that there are lots of natural sources for glutamate in food, and a clever cook can employ these ingredients to give their dishes a little extra “oomph” without resorting to MSG.

Let’s Talk About MSG

Long considered to be the culprit in an ailment that has reached “urban mythic status,” even as repeated scientific studies have absolved it of responsibility, MSG, otherwise known as monosodium glutamate, is often considered a “persona non grata” in the kitchens of American Chinese restaurants and home kitchens alike.

Blamed as the origin of a disorder known as “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome,” which is a series of symptoms which include flushing, sweating, headache, a feeling of pressure on the mouth or face, and in extreme cases, heart palpitations, shortness of breath, chest pains and swelling in the mouth or throat, MSG has never been linked to the disorder. However, because of popular belief that it is at least partially to blame for these usually fleeting and harmless (and I would say in many, but not all, cases, imagined) symptoms, many Chinese restaurants in the US advertise that they eschew it as an ingredient.

But is that the right thing to do?

Fuchsia Dunlop asked this question yesterday in an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times, and reading it made me think about my own views on the subject.

I don’t use it as an ingredient in my cooking, even though I treat with skepticism most people’s claims that they react badly to it when they eat at a Chinese restaurant.

Why am I so skeptical about this? Well, because I have watched these same folks who complain of headaches after eating Chinese food out turn around and gobble down huge amounts of processed snack foods, ramen noodles and other products that contain more MSG than most Chinese restaurant meals and show no ill effect. That is why I tend to think that many cases of this supposed syndrome are bogus and are the result of media hype, hypochondriac tendencies among some Americans and a latent xenophobia when it comes to Chinese culture. (On the other hand, I have seen someone unknowingly ingest an MSG laden broth cooked up in a dorm kitchen and break out into a wheezing, flush-faced and heart palpitating mess, so I have no doubt that with some folks, something bad -is- going on!)

So, if I am this skeptical, then why don’t I use it as an ingredient?

I don’t know, except to say that I have never felt a lack from not using it.

Since I use so many products and ingredients that include naturally occurring glutamates in my Chinese recipes, such as fermented black beans, bean pastes, soy sauce, chicken stock, dried mushrooms, mushroom broths, dried shrimp, scallops and oyster sauce, I have never really seen much purpose in having MSG around my kitchen. It just doesn’t seem necessary.

But, after reading Dunlop’s article, I am beginning to think that maybe I should drop my prejudice against MSG, go to the store and pick up a tiny bottle of Ac’cent and see what happens if I use it judiciously. Maybe I will conduct blind taste tests with friends and family.

I do know that there is one simple recipe that I have longed to replicate for years and have utterly been unable to do so that I suspect had a tiny pinch of MSG in it.

The Chinese restaurant I worked in years ago did not use MSG in food for customers, but there was a dish that the chef would make for his family and employees which I suspect had just a touch of it in its delicious sauce. It was stir fried bean sprouts with baby shrimp, and the sauce was nothing more than a tiny bit of sugar, some rice wine, a wee dash of light soy sauce, a sprinkle of salt and chicken stock. The only other flavorings were some scallions and ginger.

That was it. The shrimp were pink, plump and savory and the bean sprouts were crisp and earthy, and the sauce complemented them both perfectly.

No matter how I have jiggled the proportions it has never tasted right, and I had given up on it years ago.

I hadn’t even thought of it until yesterday when I read Dunlop’s article. Suddenly, my mouth watered as my mind was flooded with memories of that dish and how much I loved it, and how I have never, ever, been able to recreate it.

Maybe, just maybe, during this lucky Year of the Pig, I will finally be able to taste that amazing dish again.

Note: I would like to thank reader Diane for pointing out Dunlop’s Op-Ed to me yesterday.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.