A Voluptuous Vegan Italian-Arabic Fusion Pasta Dish

One of my favorite subjects of study in the world is the history of food, and how the foods of various cultures evolve over time due to human exploration, trade and conquest. I find it endlessly fascinating to examine foods such is cumin, which is a favored spice in India and the Middle East, then ask why it is also prevalent in many Mexican foods, and is even found in use in Western China. Or to trace the path of chile peppers and tomatoes from the New World to the Old World, and take note of the culinary changes these two imports brought in their wake. Or, to take note of the use of pomegranate paired with walnuts in India, Persia, and, surprisingly, Mexico, of all places.

In ferreting out these little bites of history, and tracing the origins of various flavor combinations, I find my imagination fired with the possibilities of fusing combinations of various foodstuffs together which have historical precedent, and which make sense in the context of a place and time, but which have been forgotten in the modern collective palate of the United States.

Take, for example, the case of pasta, eggplants, tomato and pomegranate.

Pomegranates are native to Persia, and across the Middle East to India, and they have spread from there to be grown throughout Europe, Asia, Africa, and North, Central and South America. Tomatoes were native to Central and South America, but after being brought back to Europe by the Spaniards, have become integral ingredients in countless cuisines, from Italy to the Middle East, to India, Africa and beyond. Eggplant may have originated in China, or India, or Persia, but what is certain is that it was introduced into Mediterranean Europe by Arab traders. And pasta, of course, was first developed by the Chinese, but was also developed in Italy. What is not much known is that types of semolina pasta are made and consumed throughout the Middle East and India, as well as Italy and Europe.

My way of fusing foods together is to take cuisines which share something in common historically, culturally and most importantly, culinarily, and then pick out some common ingredients between them. Then, I combine these ingredients in a way, which hopefully, brings out something new which my family and friends may not have tasted before, but which is firmly grounded in the traditions of the parents cuisines such that the dish comes across as a natural progression of flavors, instead of seeming to be the bastard love child of an unthinkable coupling.

Most people would not think that Italian and Arab cuisines would have much in common, but truly, they share many ingredients in common, such as garlic, lemons, various legumes, greens, eggplants, peppers and tomatoes, onions, olives and olive oil, and fresh herbs. Pasta is much more prevalent in the Arab world than most people in the US seem to know, and is used in many ways similar to its use in Italy.

There is even a fair amount of culinary cross-pollination evident in both cuisines; what many people do not realize is how much contact the Muslim world had with Italy; Arab traders brought spices and silks across to the ports in Venice which was the distribution point to the rest of Europe for hundreds of years, and Sicily, for a time, was a Moorish protectorate. As a result of these contacts, there is a much greater trading of foodstuffs, dishes and techniques than is usually recognized by the casual diner.

Which is why I loved the thought of combining eggplant, tomatoes, and pomegranate into a pasta sauce.

I have previously combined these ingredients in a traditional Sicilian sauce, Spaghetti Con Melanzane e Noci, a creamy sauce that features pureed roasted eggplant, garlic and walnuts, mixed with tomato sauce. Realizing that since the sauce was Sicilian, and that the island had been in the control of Arabs for centuries, I added a bit of pomegranate molasses–a typical Middle Eastern ingredient–to the sauce to give it some zing, and found the recipe vastly improved.

This recipe is a combination of the Sicilian dish, and my improvised Ditalini with Eggplant, Kale and Caramelized Onions, with an eye toward making a rich, but not heavy vegan pasta dish that combines elements of both Italian and Middle Eastern cookery.

In addition to the pomegranate molasses, I added chopped mint and ground cumin to the dish to play up the Arabic flavors. For contrast in texture, I sauteed some of the onions, garlic, kale and mushrooms until they were very browned and somewhat crisp. This gave a distinctive sweet flavor to the vegetables, and also made a nice contrast between the soft pasta and thick, velvety sauce and the crispy-chewy caramelized vegetables.

Finally, I will note that I left the walnuts out of the version I made last night, because Kat would be eating it. You will note that I returned them to the sauce when I wrote out the recipe–that is because I think they are integral to the dish, adding protein and richness, but since we are trying to avoid tree nuts in Kat’s diet until she is a good bit older, I compromised. If I were cooking this dish either at home for someone other than Kat and the rest of us, or at the restaurant, I would definitely use the walnuts. (Yes, I have been brainstorming about dinner specials for the past several days.)

For a garnish, I sprinkled fresh rubine pomegranate seeds over the dish to add a juicy crunch, a tart flavor and a gem-like beauty which adds visual interest.

All that was left was to name this voluptuously vegan pasta dish. I named it for Sheharazade, the clever and beautiful narrator of the Thousand and One Tales of the Arabian Nights, who eluded certain death by beguiling her husband with the power of poetic storytelling. To me, the stories of food are almost as suspenseful as Sheharazade’s magical tales of djinn, heroes, resourceful maidens and wise sages, and I hoped to evoke her magic by borrowing her name.

Pasta alla Sheharazade

Ingredients:

4 tablespoons olive oil, divided

1 cup thinly sliced onions

1 fresh chile pepper, thinly sliced on the diagonal–optional

1/8 teaspoon salt

1/4 cup minced fresh garlic

1 medium-large fresh eggplant, roasted, peeled, seeded and mashed to make 1 cup puree

1 cup basic marinara

1 1/2 tablespoons pomegranate molasses

1/4 teaspoon ground cumin

salt and pepper to taste

1 cup thinly sliced mushrooms

1 cup fresh kale greens, large veins removed, cut into a medium width chiffonade

scant 1/4 cup of finely chopped English walnuts

1/4 teaspoon pomegranate molasses

2/3 pound linguine

1/4 cup finely minced mint leaves for garnish

1/4 cup fresh pomegranate seeds for garnish

Method:

To roast the eggplant, prick the washed and dried fruit with a fork or knife all over, and set into a baking pan in a preheated 400 degree F oven until it is soft–from twenty to forty minutes. Remove, cool, peel, remove the seeds and mash the flesh with a fork, or chop finely with a knife.

Heat three tablespoons of olive oil over medium heat in a heavy-bottomed pan or skillet. Add onions, chile, if you are using it, and sprinkle with salt and cook, stirring until they turn golden. Add garlic, and keep cooking, stirring, until the onions turn deep gold and begin to brown, and the garlic is golden. Scoop out half of the onion-garlic mixture, and put into a medium sized saucepan on low heat. Add eggplant, marinara, pomegranate molasses, and 1/8 teaspoon of the cumin and bring to a simmer, stirring as needed to keep it from sticking. Cook until the mixture dries out slightly, and becomes fragrant, about five to ten minutes. Taste and add salt and pepper as needed. Set aside and keep warm. The sauce can be made ahead of time and kept refrigerated and then simply warmed by microwave or on the stove before serving.

Meanwhile, add the mushrooms and the remaining tablespoon of oil to the onions and garlic still in the heavy-bottomed pan, and cook, stirring, until the mushrooms are golden. Add the kale and walnuts, and cook, stirring, until the mushrooms, walnuts and onions are browned, and the kale leaves are darkened and starting to crisp. Stir in the rest of the cumin and pomegranate molasses, and cook, mixing the ingredients together, until fragrant. Keep warm.

When the saute is about done, start cooking the linguine in salted, boiling water. When it is cooked al dente, drain well. Return the cookpot to the heat, and dry it by allowing the water to boil off. Pour the warmed sauce into the cookpot and add the linquine. Using tongs, mix together until the pasta is well coated with sauce, and it clings well to the noodles. Add 1/2 of the contents of the saute pan to the pasta pot, and stir well, tossing with the tongs, to combine the vegetables into the sauced pasta.

When well combined, plate the pasta by twirling it into heaps in a serving bowl, and sprinkle the remaining sauteed vegetables over the top, then sprinkle the mint and pomegranate seeds over the top as well.

Makes three servings.

Is Alice Waters an Elitist Food Snob?

I had no idea so many people hated Alice Waters.

I mean, I thought Hilary Clinton was the American woman everyone all along the political spectrum loved to hate, but after reading the comments on Salon’s recent interview with Waters entitled, “Go Ask Alice,” I may have to revise my viewpoint on that matter. Maybe Hilary is now the second most hated woman in American, right behind Alice.

So, whassup with the hating? Why are a bunch of liberals and progressives frothing at the mouth over at Salon on the subject of Alice Waters and her desire that everyone in America try to eat locally and sustainably, making an effort to eat as fresh food as possible, cooked simply and eaten with our loved ones? I mean, that philosophy is hardly something out of Mein Kampf. It isn’t like Alice is saying, “I want everyone in America to take up eating babies. Yes, babies. But only if they are locally and sustainably produced and are as fresh as possible, and then are cooked simply and eaten by families and loved ones all gathered together in peace and harmony.”

Good lord, some of the posters over there sound as shrill as Ann Coulter braying about the horrific evils of democrats, progressives and liberals.

You know, folks like Alice Waters.

I should have read the subtitle to the Salon post, because it would have given me a clue as to what was going on in the letters section. It reads: “Are Alice Waters’ gastronomic principles — shop locally, eat organically — too hard to live by? A frank talk with the renowned guru of fresh food.”

Once I read the first sentence of the subhead, I realized what was happening. Folks were taking Alice Waters and her ideals dreadfully personally. At that moment, everything fell into place and I understood that what I took to be a bunch of liberals reacting to the recent full moon in a bizarre fit of sudden onset Tourett’s Syndrome, is actually a case of a bunch of folks filled with liberal guilt all trying to defend their food choices all at the same time. In other words, quite a few of them feel bad that they either do not, or feel that they can not eat locally and organically, so they become defensive, and then skewer the messenger -and- her message, vilifying Waters as nothing more than a “hippie-dippy California foodie elitist.” (I just want to say right here and right now that if anyone ever starts a public vilification of me, I hope that instead of characterizing me as some sort of hippie-dippy food elitist, I get to be called something cool like “a tin-plated dictator with delusions of godhood,” or something to that effect. Geek points to those who catch that reference.)

How elitist is Alice Waters, really? Where is it that she says, “I only want the rich to eat good food. The plebs and the rabble can just go eat cake.”

She doesn’t say that, ever. She doesn’t believe that good food should be expensive, and in many cases, it isn’t that expensive. She believes that everyone should have access to good food, rich, poor and in between.

Besides, I find it ironic in the extreme that it is now considered elitist for people to eat like I did when I was growing up as a lower-middle class Appalachian farm kid. Sure we ate well, (even when we were poor because Dad was laid off for more than a year–the farm food saved us that year) but we saved money while doing so, and we did so out of a sense of frugality, as much as because of taste and nutritive value. So, I cannot help but laugh when I hear or read folks going on about how it is elitist to eat farm-fresh food.

In fact, this irony is a symptom of just how messed up our current food system is in the US. It is just whacked. Not even two generations ago, it was quite different, and in many cases, better. Heck, even I can remember grocery store chicken tasting better than it does now, and I am only 42.

Yeah, so here I am, saying that if Salon readers think that Alice Waters is an elitist, either they are not aware of the definition of that word, or they are just feeling defensive about their own food choices.

And that is okay–one problem with Waters is that she is an idealist–an uncompromising idealist at that–and folks who not only espouse idealistic philosophy, but also -live- by it, make everyone feel inadequate and defensive when they compare themselves to the idealist. Frankly, I think that the uncompromising idealism that Waters espouses is probably detrimental to her overall message. Folks tend to stop listening when they get the idea that an idealist is saying something which runs counter to the listener’s experience, and often seems to invalidate that experience. This is not conducive to good communication.

And that really doesn’t help get Waters’ message across to the folks who most need to hear it, which includes middle-class liberals and progressives–you know, like the folks who read Salon.

Besides, when idealists will not compromise on principles, it makes others think that what the idealist wants them to do is just too hard. It becomes an all or nothing proposition. Either you eat all local, fresh food, or you are a failure, and evil person, is what people hear, even though it is not what Waters has ever said.

A glance at a few generalizations gleaned from the comments section at the Salon article, may illustrate what I mean.

Readers said that Waters can eat locally all the time because she is in Northern California where there is a mild climate so there is always fresh food. They said they cannot afford to pay five dollars for a bunch of radishes. They said that they refuse to eat only sauerkraut and sausages or turnips and beets all winter long, because “that is all that is in season.” They said only the rich can eat that way, and the rich are the only folks Waters cares about. They said that there are no farmers’ markets near their homes, so Waters should use her celebrity to go to the government and make those markets appear instead of bugging them about changing their own lives and food habits.

Let’s examine those statements. First of all, yes, Waters lives in California, and yes, there is a veritable plethora of amazing produce grown there, year round in the very mild, even climate there. That is all quite true.

What is also quite true, is that there are lots of places in the country where a large amount of crops can be grown nearly year round, too.

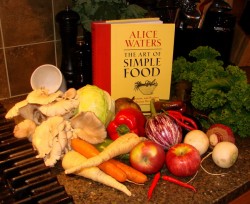

As proof, I suggest everyone take a look at the photograph above. It represents a mere fraction of the fruits, vegetables, herbs and fungi available at the Athens, Ohio, Farmer’s Market in late October. I didn’t include any of the preserves, cheese, meats, eggs or other animal products, nor the ciders, nor many other varieties of fruits and vegetables. It is just a representative sample of what I picked up this past Saturday, on an average October day. Three kinds of potatoes, sweet potatoes, two types of turnips, cabbage, mustard greens, collards and kale, sweet and hot peppers, apples, Asian pears, pears, dried horticultural beans and dried Christmas limas, carrots, parsnips, radishes, cilantro, basil, oyster mushrooms, and two kinds of winter squash.

Anyone could make a week’s worth of varied, interesting meals out of that pile of produce if they knew anything about cooking. And honestly, fruits and vegetables of this quality are not that hard to cook and make taste good–they taste so good on their own. No one is going to be stuck eating turnips all winter long here. No one. Unless you like turnips, that is–and in that case, one would hardly be “stuck.”

Oh, and while I am at it–none of these radishes cost five dollars a bunch. The Athens Ohio Farmers’ Market has produce quite reasonably priced, because we are in the poorest county in Ohio. Yes, people, Athens, Ohio, is a small town in the middle of dirt-poor white trash Appalachia, yet, we have local food year round here, and because folks here are poor–not only are the prices good, many farmers accept WIC coupons, food stamps and food vouchers given to the elderly.

Everybody shops here at the market–rich and poor alike–in a way in which Alice Waters would take pride. (Remember, she has never said that only the rich should eat fresh food.)

Does that make us all elitists like Alice Waters? If that is so, then every kid who grew up on a farm in Appalachia, eating fresh food, is an elitist, too.

And the idea of us hillbilly farm kids as food snobs just cannot help but make me laugh until I am about to wet my pants. It is just too funny.

Now, that is not to say that there aren’t places where it is hard to eat locally all the time, but does anyone really think Alice Waters is going to hate them forever if they eat frozen vegetables in the winter months? No. She isn’t going to hate them, and neither am I, but the fact remains that in the summer time, in most parts of the US, there is a growing number of farmers making a surprising amount of local produce available to the public, at prices much less than five dollars for a bunch of radishes.

Look folks, just because Alice Waters is uncompromising in her personal life doesn’t mean she will despise you and look down on you if you make compromises and only eat partially locally. She will just be happy you are making an effort, as will I and your family and your taste buds and your stomach.

As for Waters using her celebrity chef status to try and change the current food system in the US so that more people can get food from farmers’ markets–uh, what the heck do people think the woman has been doing all of these years? Hello–Earth to Salon readers! Take a look at some of the stuff Waters has done with her life, and then tell me that your assertions don’t sound like the worst of a lazy, ill-informed American’s sense of entitlement. (Which makes y’all sound, oh, I don’t know, pretty elitist yourselves…you know?)

Long before Jamie Oliver had the idea to improve school lunches in the UK, Waters’ Chez Panisse Foundation started an initiative called “The Edible Schoolyard Project.” This program, meant to be a pilot prototype for other, similar projects around the country, involves a one acre garden plot on the grounds of a public middle school in Berkley, where kids grow the food as part of class, then learn to harvest, cook and eat it.

This program was put specifically in place in a public school district where kids of many income levels and ethnic backgrounds all learn together.

Tell me, if Waters was really an elitist who only cared about rich people and lining her own pockets and food snobs, wouldn’t she have started her project in a private school which only accepts rich kids as students?

She has continued her work with The School Lunch Initiative, which is a program which has successfully removed 95 percent of the junk food from her school district’s lunch programs. That is nothing to sneeze at. Again, if all she cared about was rich folks, she wouldn’t be doing so much work on behalf of lower, middle and upper middle class school kids.

She has done all this because she is a celebrity chef, but other programs copying her success have sprung up around the country, including here in Athens, Ohio, which are NOT started and run by celebrities. The local food scene here in Athens is as big as it is because committed citizens made it so. Consumers wanted good food, farmers and food producers wanted to make a decent living, so people went to work to make it happen. And it has happened and it is still happening. And we have no Alice Waters here, making it happen–just concerned citizens willing to do the work.

I think that is what stung some people. Seeing someone who is such an uncompromising idealist working hard to make things happen tends to sting some folks’ consciences, and it makes them feel a tad bit cranky and so they lash out. Instead of using that crankiness to go forth and do something good in the world to improve their own situations, and the situations of those around them, they instead complain, and lash out against the idealist who is pointing out the path to them.

After reading that pile of invective against Waters, I decided to glance around the ‘net and see if every liberal in the world hated her but myself, and I found a similar blog entry from last month’s Diner’s Journal on the New York Times. Here, readers, even when they criticized Waters, were a lot more gentle in their wording and less dismissive in general. And I was happy to see that there wasn’t much of the fawning praise and declarations of Waters as “Saint Alice” that I had seen heaped about her elsewhere. (Okay, people, get this–folks get to be saints after they die. That’s right. No living saints. Ask the Pope, he will tel you. Yes, I talk about Saint Julia all the time, but that is because she is dead. And, I only half mean it when I call her that.)

That said, I do want to point out a little Alice Waters faux pas. Just so you know I am not one of those folks who worship her toe jam and think she can do no wrong. No–she is human, just like the rest of us and buggers things up every now and then like everyone else.

Recently, it seems, she has buggered up big time and may have done something which will only fuel the “Alice Waters is an elitist food snob” fire like gasoline poured onto a charcoal grill.

Over at The Ethicurian, a terrific food blog, there is a post written by novelist Charlotte McGuinn Freeman where she asks the legitimate question, “Why is Alice Waters involved in the building of a gated community in Montana?” The developer promised to use green building and conservation techniques, but this appears to have turned out to be a case of greenwashing. There is supposed to be a staff farmer growing food on the site, but the locals are concerned about the fact that the proposed McMansions are going to use way more water resources than the arid climate can sustain.

How is Waters involved? Apparently, the holiday edition of the Neiman-Marcus Catalog includes the offer that if anyone purchases a ten acre building site in the Ameya Preserve, Alice Waters will come and cook dinner for them and their friends.

Oh, and supposedly, she gets to open her own culinary school in the gated community.

It all sounds pretty shady to me, and has led to quite a few of Waters usual supporters (including myself) to ask a few questions, and notice that our culinary idol may well have feet of clay.

I think I may have figured out how she got involved with the Ameya Preserve project, though…back in May on Michael Bauer’s blog, Between Meals, there was a post announcing Alice Waters’ involvement in Carlo Petrini’s 2008 Slow Food Nation expo in San Francisco. The event promises to be fascinating, and full of food and fun and all that good stuff, but what I found most interesting was the mention, down near the end of the post, that the first major donotion to Slow Food Nation was “a $500,000 gift from the Ameya Preserve in Montana, which is an 11,000-acre plot of sustainable land. It was also announced that the site will be the home of the Alice Waters Culinary Institute.”

For those who are wondering why Waters may have gotten involved in what sounds suspiciously like an elitist land development project, I think we have seen the answer. They offered a generous donation to her new pet cause, Slow Food Nation, and offered her land on which to build her culinary institute. They probably highly touted the sustainability of the project, and I suspect that Waters trustingly accepted, the temptation of the donation for her pet project being too sweet to turn down.

So, knowing all of this, is Alice Waters just another elitist celebrity chef? Has she done more harm than good? Is she the worst thing since sliced bread?

Or, is she a saint of all that is edible, the Goddess of America’s Kitchen, the bringer of all that is holy, local and sustainable?

Or, is she just human, like the rest of us, trying to do good, but every now and then, screwing something up?

If you cannot guess it, I vote that she is only human: mostly good, some bad, doing her best, and often, doing a great deal of good in the process of living her life.

I like Waters; she is one of my favorite chefs in the country. I think that she has done a lot to help revolutionize American food and cookery; as much as Julia Child has done certainly. Though, I think that Waters has had more of an effect on other chefs than on ordinary home cooks, which is where Child really had a great deal of influence.

I also had one of my favorite restaurant meals in my life at Chez Panisse back in about 1995 or so. It was a fantastic experience–one of my best restaurant experiences ever, and I have to say, it was life-changing for Zak as well. He discovered at that meal that not only did he like fresh green lima beans, he really liked good olives. In fact, he discovered that the only reason he hated olives was that he had only eaten bad ones during his childhood, and so knew no better. Now, he eats good olives with great glee and gusto.

No one in her restaurant staff acted like snobs to us–in fact, they were down-to-earth, and the entire atmosphere was very earthy and friendly. They were gracious and graceful in their service. I just cannot believe that if their employer was an elitist, that they themselves could possibly be so open, accommodating, and delightful, not only as staff–but as people. I know that this will sound insufferably Californian, but these folks had a great vibe to them, and the restaurant was filled with good energy. I think that if Waters was as uncaring and awful as the opinions flying thick and fast at Salon would indicate, that Chez Panisse would not be as amazing an experience as it was.

So, I do like Alice Waters, and I cannot really believe that she is truly an elitist food snob.

That said–I do think that she may have some serious explaining to do about her involvement with the Ameya Preserve development.

Book Review: The Art of Simple Food

Alice Waters’ The Art of Simple Food is not just a cookbook.

It is also a primer of essential culinary techniques, with basic recipes for the neophyte to memorize and expand upon creatively.

It is also a guide to building up a pantry with basic items which will allow one to cook good, simple food from any fresh, seasonal ingredients available; it also gives a ground-up lesson on the most simple, basic kitchen tools needed to cook well and easily.

It is also Waters’ personal food philosophy and lifestyle manifesto, which boils down to these admonitions emblazoned on the back cover of the book:

Eat locally and sustainably; Eat seasonally; Shop at farmers’ markets; Plant a garden; Conserve, compost and recycle; Cook simply; Cook together; Eat together; and Remember food is precious.

The Art of Simple Food is a literary distillation of the Slow Food Movement, and embodies everything that is beautiful about the worldwide food revolution. Before even opening the book, this aesthetic adherence to the principles of simplicity in food are evident (and not just because the word, “simple” features in the title.) The hardcover book features no shiny dust jacket, nor any flashy food porn photographic illustrations. Instead, the spine is bound in sundried tomato-colored fabric, with the embossed, turmeric-hued boards of the cover finished to a smooth matte embellished only by the title, subtitle and author in a classic, somewhat Victorian font, and an elegant black and grey line drawing of a market basket brimming with bread and produce.

These detailed drawings continue to the end papers and are sprinkled liberally throughout the text, illustrating techniques, ingredients and concepts while also lending an air of old copper engravings and woodcuts of botanical subjects common a century and a half ago.

This artistic harkening back towards a golden age of food, farming and cookery continues throughout the text of the book, where Waters waxes rhapsodic on the superior nature of truly fresh vegetables, fruits and herbs, and the nearly divine provenance of a newly laid chicken egg. Her writing is luminous with poetic word choice which is very turn of the century, but what most stood out to me was her somewhat neo-luddite tendency to eschew the use of any electrical kitchen appliances in her cookery, preferring instead to use whisks, wooden spoons, box graters, and a mortar and pestle to take the place of mixers and food processors.

The Art of Simple Food is a truly wonderful cookbook, and an important one, but the truth is, I probably would never buy it for myself. (I was sent a review copy by the publisher.)

This is because, as I read it, I felt like Waters was preaching to the choir. It was at that moment I realized that I am not the true audience for this cookbook; I am already doing my best to live by her admonitions and I sing the same sorts of tunes Waters does on an every day basis. I don’t need lessons on how to shop at farmers’ markets, how to make a pate sucre, and how to roast a whole chicken or how to make a vinaigrette. I can do these things with my eyes closed, barefoot in the snow with one hand tied behind my back. That is just who I am. And Waters was not writing for me.

But while I would not buy this book for myself, what I plan on doing is buying several copies of it as gifts for my friends and family who are interested in learning to cook simple things that taste good, or who used to cook simply, but have fallen into the rut of using convenience foods and the microwave too often for their health, or for those who have forgotten, or worse, never known what good, fresh food tastes like.

It is for these people Waters is writing, and I think she does a very good of job of gently easing them into a different lifestyle, one where food is not just fuel for our bodies to be wolfed down quickly and without thought between jobs or on the road to another meeting. She takes readers by the hand and helps them slow down, and realize that food is much more than that–it feeds not only our bodies, but our soul, and it has the capacity to lift us up and bring us together. It not only can bring health (or disease) to the body, it can bring wholeness to the mind and heart as well.

As she leads her reader along this winding path towards treating food as a precious gift instead of a worthless commodity, Waters writes in a clear, distinctive voice which reminded me of none other than Julia Child. She has the same clarity in her explanations of technique and a very similar ability to describe the cooking process in a visceral way which not only teaches the neophyte cook to use every sense while they cook, but also makes serious cooking seem unstuffy, easy and yes, even fun.

Consider this passage, a sidebar to her basic instructions on how to make risotto:

Listen to the sounds the risotto makes as it cooks. The crackling sizzle of the rice tells you it’s time to add the wine, which makes a gratifying whoosh; and the bloop-bloop of the bubbles popping signals it’s time to add more broth.

While her onomatopoeic description is certainly droll, it is also a perfect description of what making a risotto sounds like. This sort of earthy, lightly humorous prose really helps loosen up a new cook in the kitchen, giving them something concrete to grab onto as they sail the uncharted seas of a new recipe. It is almost as good as having a seasoned cook standing close by, whispering advice into your ear.

In short, while I would never buy this for myself, The Art of Simple Cooking is an altogether lovely cookbook, worthy of a place in every budding locavore’s and newbie cook’s kitchen shelf where it can easily be referred to again and again. It is also a book worth curling up beside a warm fireplace to read while autumn’s evenings grow longer and cooler, while in the kitchen a soufflee rises in the oven and a tart cools on the counter.

I predict that it will become a favorite cookbook to give and receive in the coming gift-giving holiday season.

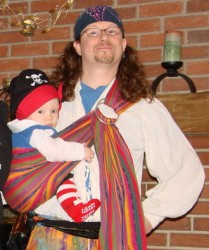

Yar! T’is The Wee Pirate Lass In All Her Glory

Shiver me timbers, who is that I see? What bairn is it who clings so tightly to her sire’s midmast, with fiery eyes and a fierce hunger for plunder and boody?

T’is naught but Kat the Wee, the tiniest pirate in all the seven seas! With her father, Mad Zak, the Psychedelic Pirate!

Yes, it is Kat and Zak dressed up and ready to go sailing off to the annual Pirate Party put on every Halloween weekend by our friends and neighbors, Howie and Karen, who gussy up their house to look like a pirate ship with tattered sails, planks, cannons and the like, and set out piles of jewels and doubloons and gallons of rum for the delectation of a thoroughly disreputable passel of pirates, wenches, scurvy dogs.

This was Kat’s first taste of the pirate life, and she took to it like a whale to water.

Obviously, she didn’t get to taste the rum, nor take part in the games of chance, nor even did she get to introduce herself to the Captain and the Lady of the ship, though she did doff her hat and wave it dramatically as I introduced her.

(Then, she threw it on the floor in a fit of disgust. She didn’t much care for the hat, adorable as it was.)

The next day, I think she enjoyed the post-pirate party brunch hosted at our house, but that is because it was a smaller crowd, with fewer loud exclamations of “Yar!” and more tasty food that included scrambled eggs with ham and cheese, roasted potatoes with rosemary and thyme, and toasted fresh whole wheat bread from the bakery down the hill.

I have a feeling that the brunch is going to have to become a tradition as well, for the folk who sail in from out of town for the pirate gathering, and for the host and hostess who work so hard to put on the event that they tend not to eat much in the way of real food the day of the party, they are so busy transforming their home into a ship.

Both events were fun, however–great fun, and were not to be missed, neither by Kat the Wee, her Psychedelic Pirate father, nor her ship’s cook mother and sister.

The Cookbook Caper: So, Did Jessica Seinfeld (ahem) “Borrow” Some Ideas from Missy Chase Lapine?

I’ve been watching this cookbook catfight develop over the past week, and I must say that I am heartily confused by it all.

Cookbook catfight? What cookbook catfight, you may wonder, especially if you don’t read the New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, or watch Fox News. (Don’t worry–I don’t watch Fox News, either. I just happened to find this story on Google.)

For those who don’t want to wade through the links, I will explain here–or rather, as there is no time, I will sum up.

Former Eating Well Magazine publisher and culinary arts instructor, Missy Chase Lapine began pitching a proposal for The Sneaky Chef in February, 2006 on the topic of sneaking pureed vegetables into child-favored dishes so that parents could get picky kids to eat something healthy even if they were not aware of it. At that time, she sent her 139 page proposal, (with 42 recipes included) to Harper Collins, without the benefit of having the services of a literary agent.

Harper Collins rejected her twice; (the reason being that they already had a title which they believed was “too similar” in their catalog, chef and food activist Ann Cooper’s Lunch Lessons, which, as near as I can tell from looking at it, is really nothing like Lapine’s book at all) the second time just two weeks before giving a contract to Jessica Seinfeld, wife of Jerry Seinfeld, for a book on the exact same subject. The reasons given for signing Seinfeld, a neophyte writer with no publication experience or professional culinary experience, over Lapin, whose resume cites experience in both fields is because of “(Seinfeld’s) name and because she was represented by one of the highest-powered literary agents: Jennifer Rudolph Walsh of William Morris Agency.” (Interestingly, Jennifer Rudolph Walsh also represented plagiarist Harvard sophomore Kaavya Viswanathan, author of How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild, and Got a Life.)

While Seinfeld worked on her book with a chef and nutritionist, Lapine found a publisher for hers, and it came out this April.

Seinfeld’s book, Deceptively Delicious, came out this month, and sales have soared, especially after Oprah had the author on her show where she touted the cookbook as “genius.”

Now, both books are on the New York Times bestseller list, and both titles are sold out at various bookstores across the country, including Amazon.com. (I know this is a fact because I have tried to find copies to peruse in various large bookstores around here, so I could give folks the skinny on how similar the recipes were. My search was in vain, however. Borders and Barnes and Noble are both sold out, and are urging customers to reserve copies for when the orders come in.)

Not long after Deliciously Deceptive came out, reviewers on Amazon began noting eerie similarities between the recipes of the books. Apparently, in addition to similar overall concepts, many of the recipes have similar ingredients.

Lapine also noticed the similarities, and is quoted in The Independent as saying:

“There are uncanny similarities between my book and Ms Seinfeld’s,” she said. “I was brave enough to put out a proposal that took five years to write, but I was naive not to use an agent when I sent it off to Harper Collins. I cannot possibly speculate about the similarities with Ms Seinfeld’s book and I’m not going to accuse anyone of anything, but I suppose it’s possible it’s a coincidence that there are so many similarities.”

The New York Times reported that executives from Perseus, Lapine’s publisher, even contacted Harper Collins after an early publicity brochure showed that Seinfeld’s book was to have a very similar cover to Lapine’s. The brocure “…showed an illustration of a woman holding carrots behind her back, similar to a drawing on the cover of “The Sneaky Chef.” Collins changed its plans for the cover….”

On the New York Times’ City Room blog, Jennifer B. Lee posted a side-by-side comparison of the two books, including some of the suspiciously similar recipe descriptions.

These recipes include Seinfeld’s “Green Eggs,” and Lapine’s “Popeye’s Eggs,” both verdant with pureed spinach; Seinfeld’s mashed potatoes with cauliflower, and Lapine’s mashed potatoes with cauliflower and zucchini; Seinfeld’s grilled cheese with pureed sweet potatoes or butternut squash tucked between cheese slices, and Lapine’s grilled cheese with sweet potatoes or carrots hidden between slices of cheese; or either of the author’s “Peanut Butter and Jelly Muffins.” (There are lots more comparisons, but you can go the City Room to see them–I don’t feel like posting them all.)

Okay, so that is the gist of it.

Both women are making a good amount of money from their cookbooks which feature the idea of slipping veggies to the kids when they are not looking. Seinfeld has been on the Today Show and Oprah, and her first print runs have sold out, and Lapine is branding her “Sneaky Chef” image into a series of “workshops, cooking classes, coaching programs, and demonstrations that teach families how to eat healthier.” According to a post on Entrepreneur.com, Lapine has signed with a licensing firm, and a series of Sneaky Chef frozen entrees are due out soon; she has also filmed a television pilot and has received a six-figure advance on a book due out next year on the subject of sneaking vegetables into men’s food. (I am sorry, but that sounds lame as hell to me. I have been good and kept my editorializing to a minimum here, but damned if that isn’t a sexist book idea that panders to every sort of bad stereotype of both men and women, and it caters the the idea of trying to deal with an adult picky eater, which just annoys me.)

Lapine’s publisher has made noncommittal comments about legal action, and Seinfeld and her husband have both denied charges that plagiarism of any sort occurred.

And really, I believe that is so. I agree with eGullet’s Steven W. Shaw when he wrote in an excellent article in Slate that Seinfeld hasn’t committed plagiarism.

Plagiarism, as he so eloquently points out, is when an author lifts entire passages from another’s work and uses it in his own work, attributing it to him or herself. Seinfeld has not, to anyone’s knowledge done this by creating a very similar cookbook to Lapine’s.

What is actually at stake is a case of copyright infringement.

However, one has to remember that ideas cannot be copyrighted. (If that were the case, no one would be able to think anything without infringing on someone else’s copyright of that thought.)

While I think it is possible that someone in the editorial department of Harper Collins may have leaked the idea of the book, and perhaps some recipes, if not to Seinfeld, but to her nutritionist/chef/ghostwriter team, I don’t necessarily think it is likely. (But it is weird that little details like hiding vegetable purees in between slices of cheese in a grilled cheese sandwich are present in both books. And I do find it passing strange that two different women could come up with the utterly foul idea of putting pureed spinach into brownies.)

So, what may have happened is a case of copyright infringement.

Except here is the problem.

Recipes are not completely covered in US copyright law. According to the law, one cannot copyright a list of ingredients; the only place where copyright comes into play in a recipe is in the way in which the author writes the methodology–the “how to” part of the recipe.

From what I have gleaned from the articles here, there and everywhere, (and I had hoped to determine by actually looking at the books today, but was foiled in my attempt, thank you, Oprah!), is that the recipes, other than concept, are not really that similar. The ingredient lists are different, sometimes only by one or two ingredients, and then, the step by step portion is written to reflect the these differences, which, in essence, leads to two legally different, if nutritionally similar, recipes.

Which means, that even if copyright infringement has occurred, it was done by someone clever enough who knew how to cover the legal bases. (Which may point to someone within the publishing industry.) Because of this, I do not think that Lapine or her publisher have a chance in hell of proving any wrongdoing on Seinfeld or Harper Collins’ parts.

Which is fine with me, because in the end, I agree with former Times restaurant reviewer Mimi Sheraton, who wrote an excellent essay in Slate where she cheerily declared, “a plague on both their houses.”

She, like me, thinks that the idea of hiding pureed vegetables in brownies to feed to picky kids is not really going to accomplish anything. For one thing, she points out that the amounts used in the recipe will end up giving the kid about 1/12th of a serving of vegetables per brownie, and when she asked nutritionist Marion Nestle (author of What to Eat) how many vitamins and minerals would be left after cooking the vegetables, pureeing them and then baking them in a brownie so that they were cooked twice, was told essentially, that the idea was “laughable.”

So there we are. The Great Cookbook Caper of 2007.

I am sure there will be more to this story, if we all just sit tight and keep paying attention to it.

Yawn.

Now I am going to curl up and read a new cookbook from a real chef: Alice Waters’ The Art of Simple Food, which just came in yesterday.

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.