Chinese Wheat Noodles 101

Italy and China have been metaphorically duking it out over which country is the birthplace to the ubiquitous noodle.

Archaeologists can confidently say that noodles as a foodstuff originated in China; recently a noodle excavated inside an overturned pot near the Yellow River was carbon-dated to approximately 4,000 years ago.

That is an old noodle, far older than any noodles which have been found in Italy.

Interestingly however, it is a noodle not made of wheat. It was made from millet, the first prevalent staple grain crop of China.

But really, it doesn’t much matter to me where noodles were first made. I never met a noodle I didn’t like, whether it was from Italy, China, or my grandmother’s kitchen in West Virginia. They are all good, soul-satisfying foods, versatile and chameleon-like, which can be both simple and elegant in presentation and flavor.

Types of Wheat Noodles

Wheat noodles are now common all over China, although they originated in the northern provinces where wheat is grown in preference to rice which cannot survive the cold winters of that region. Generally speaking, Chinese wheat noodles can be divided into two broad classes: plain noodles which consist of wheat, water and salt, and egg noodles which are made from wheat, water, salt, eggs and perhaps other ingredients. Both types are available fresh (or frozen) and dried in the marketplace, and whichever one is used depends on the recipe and the taste of the cook who is presiding over the stove.

While it is traditional to use one or the other in certain recipes, most cookbooks and cooks I personally know will freely substitute one type of wheat noodle for the other in any given dish, depending on personal preference and what they have in their pantry at a given time.

Plain noodles are a good basic noodle to have in the pantry or freezer to use in soups, cold noodle dishes and stir fried noodle dishes. They are creamy or greyish white in color, and cook up to a soft ivory color. Whether fresh or dried, they tend to cook quite quickly, so it is best to avoid overcooking them. They have a subtle, nutty sweetness of their own, but mostly, they serve as a neutral base upon which other flavors can be easily built.

The only ingredients in plain noodles should be flour, water and salt, though some fresh and frozen noodles also have sodium benzoate added as a preservative. Almost all Chinese noodles are made with salt in them so their cooking water does not need to be salted to flavor the noodles. It is already present and accounted for in the noodles themselves. They are packaged either straight in boxes or bags, or, more often, coiled together into little nests which represent a convenient serving size, which varies according to the width of the noodle. The fresh ones are very long and are coiled into bundles which are then either vacuum packed or wrapped in cellophane or plastic bags.

I have no particularly favored brand of dried plain noodles, but I have found that the company called

“Twin Marquis” makes very good fresh plain noodles which are equally good after being frozen. I have successfully used their fresh noodles in making lo mein, (stir-fried noodles) and cold noodle dishes when I wanted a chewier, more substantial texture than a plain dried noodle would give me. Their noodles are square in cross section and are comparable in width to thick spaghetti.

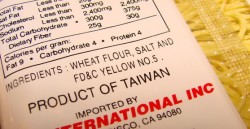

Egg noodles are generally a pale yellow in color from the egg yolks. The richness of the eggs give flavor and a meltingly tender quality to the noodles, but it behooves the clever cook to carefully examine the ingredients list of any yellow noodles with care. Some lower-quality noodle companies make yellow noodles that are colored with food dyes to simulate the more expensive egg noodles, and will charge a higher price because of it. These yellow noodles will have the same texture of plain Chinese wheat noodles, and are not worth even a few pennies more than plain white wheat noodles.

Egg noodles are widely available both fresh (or frozen) and dried, in a wide variety of widths and lengths. They are used in soups, cold noodle dishes, as stir-fried noodles and as pan-fried noodle pancakes, as well as deep fried noodles. They are delicious, and are well worth the few extra pennies more in cost to use regularly, though I do tend to keep a wide selection of both plain and egg noodles in my pantry and freezer so that if I get the urge to make any particular noodle dish, it is likely that I have any noodle necessary for the job. Like plain wheat noodles, egg noodles are often packed in nest-like bundles or in straight packages when dried and are available coiled into neat bundles when fresh.

Some egg noodles are also flavored with shrimp roe or colored and flavored with spinach. The shrimp noodles are a dark salmon-tinted tan, while the spinach noodles tend to be a soft sage green in color. Beware of bright mint green noodles–check the label–they usually are nothing more than plain noodles colored with food dye! These special egg noodles are often used in appetizer dishes and with soups, where they add color and subtle flavor to the bowl.

Once again, I am very fond of the fresh egg noodles from Twin Marquis, which I can find both in the refrigerated section and the freezer case of most local Asian markets. Nasoya Chinese Style Egg Noodles are widely available in most American supermarkets in the refrigerator section where tofu and vegetarian meat substitutes are sold. I used them the other night in making cold sesame noodles, and found that they turned out as well as a batch I made with some Twin Marquis noodles. The added bonus is that they are very easy to find and they have more explicit cooking instructions on the package than are available on the packages of most Chinese made noodles. (Though my method for boiling noodles is even better than what Nasoya suggests on their package.)

Italian Pasta vs. Chinese Noodles

Unlike Italian pastas which come in a dizzying array of often fanciful shapes and sizes, Chinese noodles, both plain and egg, are most often straight or curly and long. Their shapes in cross-section are round, square or rectangular, with thicknesses ranging from nearly hair-fine to as wide as a woman’s thumb. While it is true that there are traditional pastas which are handmade and molded into different creative shapes with fingers, most commercially available Chinese noodles look similar to Italian spaghetti, angel hair, linguine and fettuccine.

Speaking of Italian pastas, many cookbooks recommend that a cook substitute a similarly shaped Italian pasta if Chinese noodles are unavailable.

I disagree vehemently with this advice. First of all, decent wheat-based Chinese noodles are increasingly available in American grocery stores, and even in small towns and medium sized cities, there are Asian markets. If all else fails, one can order any Chinese ingredient one cannot find in town from Internet-based businesses, usually for very reasonable prices and moderate shipping costs.

Secondly, and most importantly, I disagree with the advice to substitute Italian pasta for similar-sized Chinese noodles on the grounds that the texture will be all wrong. Chinese noodles, even the dried ones, are softer and more tender than dried Italian pastas. This is because the types of wheat used to make these products are totally different. The wheat used to make Italian dried pastas is very hard, among the wheat types with the hardest kernels. These kernels are ground coarsely into a yellow-grainy flour called semolina, which is then used to make machine-made dried pasta which cooks up to a noodle with a very distinctive chewy quality.

Chinese noodles are made with wheat with softer kernels, after they are ground into a silky-smooth flour. Whether made by hand or machine, these noodles, while fairly sturdy, are more brittle than Italian pasta, and should be handled a bit more carefully. They cook much more quickly than Italian pasta, which is why I suggest a simple boiling method below to use in order to avoid overcooking Chinese noodles.

The only Italian style pasta I have ever managed to successfully substitute for Chinese noodles, are the hand-made soft wheat Northern Italian style noodles made by Rossi Pasta. These noodles are made from softer wheat than machine made noodles, much in the same way that Marcella Hazan describes as being typical of northern Italian handmade noodles. Semolina is never used in home made pasta in the north of Italy; instead, Hazan says that a flour similar to American all-purpose flour is used, which gives the finished, cooked noodles a tender, yet springy texture. This is similar to the texture of either fresh or dried Chinese noodles.

How to Boil Chinese Noodles Successfully

Boiling can be the primary cooking process for Chinese noodles, resulting in an end product: cold noodles for a chilled appetizer or salad, or hot noodles for a soup. Or, it can be a method of pre-cooking noodles in order that they may then be used to make noodle pancakes or stir fried noodles such as lo mein or chow mein. At any rate, in any given Chinese noodle recipe, the first step is often to boil the noodles so that the recipe can commence.

Because Chinese wheat noodles are made from softer wheat, they do not cook the same way that dried Italian pastas made from very hard wheat do. It is very easy to over-cook these noodles, and end up with a mushy, slimy mess if one follows the usual method we are all taught for Italian pasta of boiling continually in salted (and sometimes oiled) water.

Some cookbooks suggest bringing the water to a boil, then adding the noodles, which will stop the boil. Then, the cook is instructed to turn the heat down to a bare simmer, and cook the noodles gently, stirring all the while.

That works fine so long as one does not have an electric stove which does not respond instantly when the heat is turned down, or one is not cooking in a thick-walled pot that retains heat well. In either of these cases, the cook is left with water boiling anyway, and risks overcooking her noodles through no fault of her own, since she followed the directions to the letter.

This is a simpler method to cook tender Chinese noodles, whether they are dried or fresh. I learned it from a Chinese chef at the restaurant where I used to work, and then witnessed several Chinese friends cook their noodles the same way. All of them told me it was the way their grandmothers taught them.

You bring your water to a boil. It should be in a large pot with plenty of water and room for the noodles “to swim around” as a friend once told me. (This part is like cooking Italian pasta–you need lots of water to cook noodles, no matter where you are.)

You do not salt it, as there is salt already in the noodles. You do not add any oil, either, as it serves little purpose in keeping the noodles from sticking–that is what you have chopsticks for! (When I asked the Chinese chef if he ever oiled the water with sesame oil or the like to keep the noodles from sticking, he looked at me like I had lost my mind. “What, and waste expensive oil? Why do you think we have chopsticks?” he said, shaking his head as he stirred a pot of noodles with a pair of long, cooking chopsticks.)

If you are cooking fresh noodles, take them from their package, and loosen them up, spreading them out on a clean plate. Fluff them up so they are not all stuck together–if you just dump the coiled contents of the pack into the water as is, you will end up with an unruly glob of sticky dough instead of noodles happily cooked into springy separate strands.

If you are cooking dried noodles, remove from the package the amount of noodle nests or straight noodles you are planning on cooking. (Check the package to see how long they suggest cooking the noodles in any case–even if they instruct you just to boil them, they will give you an estimated length of time. Notice that it is no longer than five minutes, which is much less time than it takes to cook Italian pasta.)

Do not overcrowd the pot! It is better to cook in several batches than it is to add too many noodles to the pot at once! I usually use seven quarts of water for a half pound to a pound of noodles.

Have ready beside the cooking pot, a pitcher or measuring cup of cold water. A colander should be in the sink, and if you are cooking several batches of noodles, you will need a mesh skimmer to remove the noodles from the boiling pot without pouring out the water.

When the water comes to a boil, put in your noodles. For dried noodles, just drop them in. For fresh, in order to keep them from wanting to clump together, lift them with both hands and sprinkle them over the surface of the water, scattering them over the pot.

As soon as the noodles go into the pot, your water should stop boiling, because the cool noodles have brought the temperature of the water down. This is good. While you are waiting for the water to come back to the boil, stir the noodles with a wooden spoon or better, a pair of chopsticks. Dried noodles that are coiled into nests need to be unwound so they will not stick together, and fresh noodles need to be separated as well.

While you are waiting for the water to come back to the boil, watch the clock. When it boils, pour a half cup to a cup of cold water into the pot to stop the boil. It should go down to a bare simmer. Stir the noodles again. Depending upon the thickness of the noodles, they may be done now–very fine noodles cook in about one to two minutes. If they are done, either remove them with a skimmer to a colander to drain in the sink, or pour them into a colander. If they are not done, repeat this process as necessary until they are done.

I use the chopsticks to pull out a noodle or two to test as I cook.

When they are finally done, remove them from the heat, pour the contents of the pot into the colander and begin rinsing them in cold water. This step is of paramount importance; rinsing in cold water removes any residual dissolved starch from the outside of the noodles, which keeps them from sticking together, and it helps firm the noodles up slightly, giving them a springy, bouncy quality under the teeth. I learned this from the old Chinese chef, and have since found it mentioned in a couple of out of print Chinese cookbooks from decades ago, but few modern cookbooks mention it.

If you are serving them cold, rinse them completely, using the water to chill the noodles thoroughly, while your clean fingers massage and detangle the noodles. If you are serving them hot, and are not going to cook them further (by stir frying, pan-frying or adding them to soup), then rinse them briefly in cold water, then switch to hot water, and then shake them in the colander to dry them. Rub a bit of sesame oil in them to keep them from sticking together, then put them back in the cooking pot to keep warm until they are ready to be served.

If they are going to be cooked further, go ahead and rinse them thoroughly in cold water. Then, you can hold them until you need them by keeping them submerged in cold water, which continues the firming up process. Many noodle shops precook noodles, then keep them soaking in cold water until they are served. Then, they are drained, scooped into warmed bowls, and topped with boiling soup which instantly warms the noodles to serving temperature. Noodles to be served cold also can be treated in this way: you can soak the noodles while you ready the sauce or dressing they will be served with.

Before tossing with the dressing, sauce, be certain to drain the noodles well so that the sauce is not unduly diluted by excess water. I sometimes use paper towels to blot the water off as well as shaking and tossing them in a colander.

That is it–my method for boiling Chinese plain or egg noodles in order to achieve the best texture and flavor. It sounds difficult and time consuming, but that is only because I explained it so thoroughly. It is really simple, and takes only about five to ten minutes from when the noodles go into the pot and when they emerge from their cold shower, ready to be cooked further or dressed up as I see fit. Noodles cooked this way are good to the last drop, or rather, string–as Kat illustrates here.

Tomorrow, look for a recipe featuring cold boiled noodles dressed in a delicious spicy sauce that makes a perfect light supper for a sweltering August evening.

Until then, here is a list of recipes I have already presented which use Chinese wheat noodles.

Za Jiang Mein: Wheat noodles with a meat and tofu sauce from Beijing–a great comfort food.

King Du Noodles: A variant of za Jiang Mein, which is sweeter and spicier, with black mushrooms.

Char Siu Lo Mein: Stir-fried fresh noodles with home-made roast pork, mushrooms, and greens.

Chicken Lo Mein: Once again, with greens and mushrooms. I love mushrooms.

Hunan Cold Spicy Noodles: They’re cold, they’re hot, their cold….whatever they are, they’re good.

Bad News From Maryland: Health Code Violations Close Lotte Plaza

Thanks to several observant readers from the Baltimore/Washington metro area, I just found out that the Korean supermarket where I used to lead educational tours for neophyte American cooks who were interested in Asian food has been closed due to egregious health code violations.

I had noticed when we visited the store last August that it hadn’t looked as clean as I had remembered it, but apparently things are even worse now.

Mouse droppings, live rodents, rotted meat and improperly cooled seafood were among the violations cited by the Howard County health inspectors in the decision to close the store down. Tipped off in May, the health department had been investigating the store throughout the summer and had issued warnings to the owners and management that unless they cleaned up their act, the supermarket would be closed.

WJZ television news reported that a follow-up inspection in June revealed no progress in addressing the health issues, so on July 6, a citation was issued demanding clean-up and repairs of broken refrigeration units. The owners did not comply so the supermarket, which is one of the largest Asian markets in the area, was closed yesterday.

Health officials will not allow the market to reopen until they violations are addressed properly.

According to the Washington Post, a health official worked through Korean interpreters in order to assure that the Lotte president and vice president understood the health code violations, and had been doing so since April.

Several of my readers additionally report that they had stopped shopping at the Lotte Plaza because of their own discomfort with the level of cleanliness which has deteriorated over time.

I remember when I lived in Maryland years ago, how clean and pleasant the store was to shop in–I hope that the management cleans the place up and it can return to being a healthy, safe place to shop, but with the level of problems mentioned–I am not certain that this will happen, certainly not in a timely fashion.

Coming on the heels of news that Chinese seafood sold in the US was contaminated with unapproved drugs and food additives, this story is a blow to consumer confidence in Asian foods and markets in the US.

As for me–I am still buying Chinese foods–soy sauces, bean pastes, noodles and the like–in large part because the American made substitutes are just not as good in flavor or quality. I will also buy Taiwanese products, Korean products and products from Japan.

The future will only tell where these issues will lead us.

Thank you to the handful of readers who sent me email letting me know about this unfortunate issue.

An Introduction To Chinese Noodles

There is nothing more delicious, comforting, appetizing and filling than a bowl of well-prepared noodles, whether one is dining in the East or the West. Noodles are a favorite food among people of all ages, and nearly every culture where grain is consumed has created some sort of noodle to beguile the senses and fill the stomach.

Few countries can claim as many different sorts of noodles as China, arguably the birthplace of the noodle as a foodstuff. Over a period of many centuries, noodles have been developed and refined in China, until they exist in a culinary class all by themselves. They are eaten all over the myriad regions of China, and they are eaten in many different forms and types of preparations: from cold appetizers to soups to savory stews, noodles are a mainstay of the Chinese diet.

There is no way to adequately enumerate the plethora of noodle types, preparation and recipes in a single essay or article, so small post is just meant to whet the appetite for more writings to follow. But, a concise summary is possible, and so we begin.

A visit to a well-stocked Asian grocery store will reveal a dizzying array of noodles. They are usually grouped in their own aisle or aisles, but there are also offerings of frozen noodles and fresh, chilled noodles in the refrigerated section. To the beginning shopper, the broad selection is challenging, and can cause frustration if one doesn’t know exactly what one ones and needs for a given recipe or cooking style.

To simplify the issue of Chinese noodles, it is best to remember that they fall into three broad categories: those made of wheat, those made of rice and those made from other, often vegetable, not grain-based, starches. Within each of these three categories are myriad different types, shapes and sizes of noodles, each one useful for different recipes.

Wheat noodles are the most prevalent staple food, along with buns, steamed breads and fried cakes, in the colder, northern regions of China. The climate is more conducive to the growing of wheat than rice, and so cooks of these regions have developed a great number of delicious ways to use the many different types of wheat noodles available. The love of wheat noodles is not relegated purely to the northern parts of China, of course; they are now eaten all over China.

Generally speaking, wheat noodles are made in two ways: with and without eggs. Both types are available either fresh (or frozen) and dried, and they are also available with or without additional flavorings and colorings such as shrimp roe and spinach. Some noodles are salted, and others are not; the easiest way to determine whether a noodle has salt or eggs in it is to look at the ingredients. They are always noted in English on the back, and that way, if you want egg noodles, you can be assured of getting them, instead of relying only on the yellow appearance of the noodle, which can be accomplished with food coloring agents.

The second broad class of Chinese noodles are the ones made of rice flour. These noodles, which originated in the rice growing regions of southern China, are always made simply of rice flour and water, and like wheat noodles, they are available both fresh (or refrigerated or frozen) and dried. The fresh ones are pure, pearly white, and glisten with a light coating of oil to keep them from sticking to each other, while the dried ones come in translucent bundles which look like cellophane or plastic.

Rice noodles, like wheat noodles, can be used for many different dishes, but, because they are made from rice, which lacks the cohesive springiness of gluten, they are treated differently than their wheat-based cousins. Their texture, which is different from wheat noodles because of the lack of gluten, can be by turns tender or chewy, smooth or crisp, slippery or sticky. Their flavor is mild and takes on the flavor of whatever they are cooked with.

The third category of Chinese noodles are the ones which are made from starches other than those derived from grains. This group includes bean-thread noodles, which are also known as glass noodles or cellophane noodles. These are made from mung bean starch, and they are usually very thin, hair-like noodles sold in dried bundles. Soaked before use in soups or stir fried dishes, bean thread noodles turn from brittle, nearly transparent threads into slippery clear noodles which have a unique texture and no flavor to speak of. They are prized for their texture, their translucency, and their incomparable ability to soak in the flavors of the surrounding dish.

Other starches are used to make Chinese noodles, including those derived from sweet potatoes and tapioca. The skin that forms on the top of heated soy milk, called yuba, is also used to make very chewy noodles, and highly compressed tofu is cut into thin strips to be used in cold noodle dishes.

As if the great variety of noodles alone was not confusing enough to the novice, the Chinese have developed many different cooking methods to bring out the best in these versatile foodstuffs. Texture plays as much of a role in Chinese cookery as flavor does and over the centuries the resourceful cooks of China have come up with a variety of ways to cook their noodles, often using one or two different methods in concert to create a very specific and particular texture which is prized in various noodle dishes.

Even the simple act of boiling wheat noodles is done differently in China than we are used to using to boil pasta in the West. Because the wheat used to make Chinese noodles is a different variety than those used in Italian style pasta, it is easy to overcook the noodles into a starchy, tasteless mush. So, the Chinese do not just dump their noodles into boiling water and time them until they are done. The temperature is controlled precisely by stopping the boil several times during the cooking process, leading to a noodle which has a greater elasticity and is not overcooked.

Other techniques which are used to create excellently flavored and textured noodles include steaming, deep frying, oil blanching, and stir frying.

Most Chinese cookbooks for the American cook do not enumerate these techniques; I have been lucky enough to learn them directly from Chinese restaurant chefs, home cooks and from out-of-print cookbooks, and over the next few months, I will pass them along here in my blog. None of them are difficult or onerous and the results are fantastic, and are well worth thee small effort that is involved.

As you can see from the smile on Kat’s face, well-cooked Chinese noodles are good to the last bite! (These were thin eggless Chinese wheat noodles boiled then rinsed and chilled with cold water, and dressed with a bit of chicken broth, soy sauce, cilantro, scallion and sesame oil. That was her version of the very spicy cold noodle dish Zak, Dan and I had for supper.)

The next posts in this series will be all about Chinese wheat noodles-what types there are, what they are used for, how to cook them, and recipes featuring them. Then, I will cover rice noodles, and other noodles made from various starches, with recipes and cooking methods. Finally, somewhere along the way, I will do some book reviews on tomes relevant to the cooking of all kinds of Chinese noodles.

The Week From Hell

I guess it is obvious that I have not posted anything in over a week.

There is a reason for that.

It all started last Friday night.

Kat developed a fever. When we woke up Saturday morning, it was up to 104.1 F.

This was upsetting, obviously, not only because we didn’t know what was causing it, but because this is the first time she has been sick, and of course, the pediatrician’s office was not open.

(Why is it that kids only get really sick when the doctor’s office is closed?)

So, we called the doctor’s answering service, and he called back quickly. We had sponged her off and given her Tylenol and the fever had come down to a more acceptable 101.5. He said we were doing the right thing, and to keep doing it, and he suggested we use Motrin in addition to the Tylenol if the fever went above 103 again. And we were only supposed to go to the ER if the fever soared and would not come down or if she manifested any symptoms other than the sniffles.

Well, we held on until Monday, keeping her dosed up on anti-inflammatories and giving her plenty of fluids. Then we took her to the doctor, and he checked a urine sample, because he had caught some kids with this virus which has been going around with UTIs, which are really bad for babies.

Meanwhile, Tristan, my thirteen year old Siamese cat, died on Saturday night. He has been sick with chronic upper respiratory disease his entire life, and it was finally too much for him. We had been medicating him, but the stress of being medicated did him in. I found him Sunday morning.

Morganna came back from her work housesitting and dogminding with asthma and allergy issues from the dog hair, so she was not feeling well.

The kitten fell into the toilet, which thankfully, was flushed and clean.

Then, she jumped onto my bed, because that is the first place to go if you fall into water, apparently.

Kat’s fever stopped abruptly, and we felt like all was well.

Morganna developed a UTI.

So, off to the doctor Morganna went.

They prescribed her with sulfa, because she, like me, is allergic to penicillin.

She has developed an allergy to sulfa, too, just like I have. She broke out into spots and then started vomiting in the wee early morning hours.

Kat also broke out into a blotchy red rash.

And then Kat’s doctor called us to tell us that her urine culture had come back with a high amount of bacteria. So, back to the doctor both of them went. (Meanwhile, another cat is sick, and my allergies go into overdrive–some sort of pollen must be out and about attacking me viciously.)

Zak is now on a first name basis with the pharmacist.

We still have a cat who is sick.

Kat had what is called “roseola,” which is caused by one of the gazillions of herpes viruses that lurk around and attack humanity. All it really does is give a high fever, some sniffles, loss of appetite, body aches, crankiness and sleepiness. The worst is the fever, which can cause complications. Then it all goes away, and the rash comes on.

As for her urine culture, they took a second one on Thursday, and we will hear the results of it on Monday after it has had a chance to grow all weekend.

It may be that there is a structural problem with her urinary tract, but until we know for certain, I won’t go into it.

Morganna is fine, and is back at her dogsitting post. No more sulfa for her ever again.

Next week, she will be going to New Hampshire and NYC with Zak’s parents.

One cat is still sick, but it is probably nothing.

My allergies are still awful, but I can live with it.

The kitten has not fallen into any toilets recently, but she keeps trying to get stepped on. Currently, she is trying to destroy an area rug which apparently needs to be attacked violently and mercilessly. It must be an evil rug.

So.

The upshot of all of this is that I will be back to talking about food, Chinese food in particular, on Monday or Tuesday. I promise.

God willing, and the creek don’t rise, as they used to say back home in West Virginia.

What Would You Eat For Your Last Meal?

I was asked by a reader to contemplate what I would like to have for my final meal, if I could plan such a thing.

That is a hard one. Not that I dislike the idea of contemplating death–having faced it once or twice in my life, I am not particularly disturbed by the thought of shuffling off my mortal coil.

What is hard about this request is to narrow down which foods I would want to have as the last taste in my mouth.

I think I would want something amazingly scrummy, like Thai Chili Basil Squid–a dish which I have not made at home, since squid are thin on the ground here in Ohio, but when I am in an excellent Thai restaurant, I order it every time. It is filled with the scent of the ocean, the incendiary power of Thai bird chilies, the sweetness of shallots and garlic and the herbal song of basil leaves, all held together by the sour tears of lime.

It is a wonderful dish, so lighthearted and joyful. It is like singing “Simple Gifts” and dancing a circle dance on a sunny May morning.

That is a fine thought if my last meal was in the spring, but what if it was in winter, and the sky was grey and cold, and snow blustered in the air?

Ma Po Tofu, steamed rice and Gai Lan and Shiitake Mushrooms with Oyster Sauce would be my last meal of choice. For whatever reason, Ma Po always makes me feel comfortable and comforted, like a warm quilt wrapped around my tastebuds. And the crisp, snappy stalks and velvet leaves of the gai lan pair perfectly with the fleshy musk of the mushrooms. These vegetables, too, are a comfort on a cold winter’s night, especially with a mug of smoky lapsang souchong tea.

What if my last breath were to come in October, my favorite month? What if I were to breathe my last on a morning when mist rises from grass lightly tipped with silvery frost, burned away by a golden sun blazing in an azure sky, setting the scarlet maples aflame with her brilliant rays?

Ah, then it would be simple.

A bowl of pinto beans cooked with a ham hock, onions, garlic and cumin, garnished with raw onions and cilantro, a basket of sweet cornsticks flavored with chili and cinnamon, a mess of greens cooked with bacon, onions, garlic and chili and dressed with balsamic vinegar, with fresh apple cider to drink.

And were I to go in summer, what would I want?

Nothing more than a pie made from freshly picked sour cherries wrapped in a crust of lard, butter, flour and a touch of sugar.

The truth is, I cannot decide what I would want for my last meal, in large part, because I cannot predict being able to predict when death will come. Death has always been a bit of a trickster, coming like a thief in the night, where none shall know his passing, so thinking about what I would plan to eat were I to somehow know when to expect his knock upon my door is a bit odd to me.

I suppose I could look at it this way: what would I plan to serve Death when she came calling for -our- last meal together. That makes a bit more sense, for as I was raised by southerners, I find it to be very rude to sit and eat without asking my guest to sup with me.

So, the question could be, and perhaps it would be better answered this way: what would I offer Death when he comes on his errand to fetch me?

The answer to that is simple: the best of what I can offer.

It is always foolish to slight a guest, particularly one so implacable and powerful as Death.

So, what would -you- want for your last meal?

Or, if you prefer–what would you sit down to eat with Death on your last day?

(And Bry, or Dan, or Zak, if you say, “salmon mousse,” I shall toss a fish at you.

(Thank you to Hillary from Chew On That for this evening’s thought-provoking post idea.)

Powered by WordPress. Graphics by Zak Kramer.

Design update by Daniel Trout.

Entries and comments feeds.